Nations of Canada

The Birth of Quebec

In the twentieth instalment of ‘Nations of Canada,’ Greg Koabel describes how Samuel de Champlain and Récollet missionaries established a fledgling French colony in what we now call Quebec City.

What follows is the twentieth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialised Quillette project adapted from Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name.

Previous instalments in this series have focused on the growing alliance between Samuel de Champlain and his Wendat and Algonquin trading partners during the late 1610s and 1620s. As we saw last time, this development did not create an immediate social and economic upheaval for these Indigenous groups—who were used to the ebb and flow of trade-driven geopolitics along the St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers. Rather, the French were integrated as a new (albeit somewhat more exotic) trading partner into their existing network.

This time, we’ll change our vantage point, and look at the expansion of the fur trade from the perspective of the newly arrived French-Canadians—even if, historically speaking, the use of that latter term is anachronistic. Quebec (the site of what we now know as Quebec City) was then not so much a colony as a trading post. During the winters, the settlement was abandoned by all but a handful of residents. And even at the height of the summer trading season, Quebec’s population consisted largely of traders, necessary artisans, and French corporate officials. So far, no one had established any permanent farms, and the colony still relied on supply runs from France to feed itself.

However, the seeds of a self-sufficient colony (and much later, the nation of French Canada) were already emerging. Regular trade with the Wendat opened up vast new quantities of fur from the Canadian interior (thanks to the Wendat’s Algonquin trading partners). And the latest joint Franco-Indigenous raid on Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) territory in what is now northern New York State had ensured a period of relative security on the local river network. The profitability of Quebec as a trading colony was no longer theoretical.

But, as has often been the case in this story, progress on the Canadian side of the Atlantic was hampered by political turmoil on the European side.

In 1616, Champlain and Joseph Le Caron, head of the Récollets’ missionary project in Canada, sailed for France, having just spent several months among the Wendat. Their shared goal was to promote the Canadian colony back in the salons of Paris, especially among the project’s deep-pocketed Catholic backers, who saw saving souls as being at least as important as earning dividends.

Earlier French missionaries had naïvely believed that Indigenous hearts and minds could be won simply through energetic Christian preaching. Le Caron’s experiences among the Wendat had convinced him that large-scale conversions wouldn’t come until Indigenous communities adopted a sedentary French-style farming lifestyle in the shadow of French settlements (whose colonial inhabitants would be expected to model Christian virtues and habits for the benefit of Indigenous onlookers). But of course, those villages didn’t yet exist in Canada. If God’s glory were to be spread to the New World, France would have to invest in a greater colonial footprint.

The missionary message proved popular among France’s pious elites, whose political star had been ascending since the French court had come to be controlled by Marie de' Medici, the mother of King Louis XIII (then still in his teens). Champlain and Le Caron were also bolstered by Pierre Biard, the French Jesuit whom we met back in the seventeenth instalment. He’d been captured (and released) by the Virginian-based English colonists who’d destroyed French settlements in Acadia, and had published an account of his adventures, along with a plea for France to support a renewed missionary presence in Canada.

Meanwhile, Marc Lescarbot (whom some will remember as a minor character from our twelfth instalment), published his own history of France’s fledgling colonial efforts—this one taking a more nationalist approach. A florid writer who fancied himself a seventeenth-century Virgil, Lescarbot predicted that “in a New France, all of Old France may one day rejoice with profit, glory, and honour.” The combined forces of nationalism, missionary fervour, and profit-seeking all seemed to be aligned in encouraging greater French investment in the Quebec enterprise.

Some disagreements did remain, however. The Récollets demanded a ban on Huguenots (i.e., French Protestants) in the colony, whose presence, they believed, would compromise their missionary work among the Indigenous population. Why would Indigenous communities believe the message that Catholicism represented the one true faith when the priests’ own European neighbours and shipmates were preaching a different message?

In principle, Champlain (an apparently sincere convert to Catholicism) had no objection to this Récollet stipulation. But as I’ve taken pains to note in the past, Huguenot traders were powerful players in Normandy and France’s western trading ports—the areas of the country most deeply vested in the fur trade. Cutting them out would risk the possibility that these frustrated Protestants might continue to trade independently with Indigenous fur suppliers, thus undermining the monopoly structure upon which Champlain’s whole plan had been based.

Another objection raised by French traders had nothing to do with religion: They simply liked the limited French footprint in North America just as it was, and didn’t see the need for costly colonial infrastructure. Clearing land for agriculture, wasting money on the construction of European-style villages and churches, and paying France’s farmers to move their families to the other side of the ocean was not what they’d signed up for. Nor were these traders eager to see Indigenous hunters converted into farmers—an idea that Champlain was promoting—as this labour shift would necessarily diminish the supply of pelts that could be shipped back to France.

There was another problem, too, one that students of French history may be anticipating. The child-king Louis XIII was approaching adulthood, and so his mother’s time as France’s de facto ruler was coming to an end. This meant the political situation was highly unstable. The young King was old enough to be forming the ideas and relationships that would define his (as things turned out) lengthy reign.

The greatest beneficiary of the unsettled nature of French court politics during this period appeared to be 27-year-old Henri II de Bourbon, Prince of Condé (whose name you might remember from instalment sixteen). Condé was the most senior of the king’s royal cousins, and so stood in line for the throne behind Louis and the King’s younger brother, Gaston. He was an ambitious figure, and had long resented the Queen Mother, who’d limited what he saw as his rightful role on the regency council. While Champlain had been travelling among the Wendat in 1615, these tensions boiled over into civil conflict. Condé attempted to forcibly remove the Queen Mother’s chief advisor, the ill-fated Italian Concino Concini, 1st Marquis d’Ancre. As had been a common trick during France’s devastating Wars of Religion, Condé grafted his dynastic ambitions onto religious grievances: He mobilised the Huguenots, who worried (not unreasonably) that de' Medici and her hardline Catholic advisors were turning their backs on Henri IV’s somewhat pluralistic religious settlement.

The result was a brief rebellion that threatened to cast France back into the cauldron of civil war. Fortunately a political agreement was reached in May 1616, just weeks before Champlain arrived back in France. Condé agreed to recognise Concini’s place in government; and in exchange, the Prince was brought onto the royal council and granted several important regional offices.

This was, however, just a temporary compromise. Tensions remained high, and would only intensify as young Louis grew into his role as King. The Huguenot anxieties that Condé had exploited remained all too real. And confidence in the religious compromise King Henri IV had established with the 1598 Edict of Nantes was badly eroded.

In other words, France was a combustible place, and would remain so for the foreseeable future.

Champlain was more than just a neutral observer to this drama. Beginning in 1612, as readers may recall, Champlain had relied on Condé to serve as his influential patron at court. In formal terms, Condé had become viceroy of all French possessions in the New World. And so, without really intending to, Champlain and his commercial allies had inserted themselves into a high-stakes political game.

As many predicted, the uneasy truce at court broke down within weeks, with disastrous consequences for the Canadian project. Condé was outmanoeuvred by his rivals, and thrown into the Bastille on suspicion of treason. Where that left the Canadian colony, no one knew. Among those who worked on the ground in Quebec, this lack of long-term stability encouraged short-term thinking.

As Champlain once again returned to Canada in 1617, he must have been tired of this familiar routine, which he’d been going through for more than a decade by now: He would sail for Europe, fresh off of some new achievement in Canada, only to return a few months later, dejected by some disappointment in France.

Ultimately, he was a skilled diplomat in two worlds, but master of neither. When dealing with Indigenous nations, Champlain faced barriers of language and culture; while in France, on the other hand, he was a small fish navigating the power politics and religious schisms of one of Europe’s great powers.

I noted above that the initial arrival of French traders and explorers did not seriously upend the Wendat way of life. However, the same wasn’t true for the Innu of (what is now) northeastern Quebec. They’d served as important middlemen in the early years, before the French presence had penetrated upriver toward (modern) Quebec City and Montreal, but now felt abandoned—especially as they’d refashioned their economy to focus on trade, and so had lost some of the skills required to produce many domestic goods. As I’ve discussed at greater length in previous instalments, Champlain was working on turning this crisis into an opportunity. With Quebec’s development as a colony being held back by a serious manpower shortage, he believed these two problems could be combined into one solution—the re-settlement of Innu populations within a French-style farming colony.

In theory, Champlain was arguably onto something, even if (as more enlightened and modern sensibilities would indicate) colonial efforts to move Indigenous populations around from place to place en masse often end badly. In the decades following Champlain’s career, hybrid European/Indigenous communities did become a key part of the French colonial project. But the formation of such blended communities required detailed knowledge of each other’s social practices, and a willingness to engage in political compromise. In his relations with the Innu, Champlain—who, in other respects, often proved himself at least somewhat adept at reading the Indigenous room—proved deficient on both counts.

As discussed in the previous instalment, a flash point in the French–Innu relationship was sparked in 1617 when two Frenchmen were killed by Innu traders following a disagreement. The details of the crime (as the French defined it) are not as important for our purposes as the gulf it exposed in cultural attitudes. The Innu practice at such times of crisis was to offer condolence gifts that would help heal the rift caused by the violence. For the French, on the other hand, murder could not be smoothed over through material means. Champlain and the Récollet missionaries instead demanded that the killers face some form of European-style criminal justice. Which is to say that while Indigenous groups focused on the social health of the collective, the Frenchmen—following the Western tradition—were fixated on the individual culpability of the men who’d done the killing.

The French demands may not seem controversial to a Western reader, but they were seen as akin to a declaration of war from the perspective of the Innu. Within their Indigenous world, a demand for blood indicated that a communal friendship had been broken, and that the relationship was now one of rivals, or even outright enemies.

Further exacerbating tensions was the issue of land stewardship. From the beginning, the French colonial project had been studiously ambiguous when it came to this area. Unlike the Spanish, the French hadn’t yet made any sweeping territorial claims by right of conquest. Which makes sense since, by this point, they hadn’t actually conquered anyone.

Rather, the geopolitical context of the St. Lawrence region had allowed the French Crown to simply assign lands to Champlain’s colonial Company by royal decree—but this was strictly an intra-French arrangement that Indigenous nations had no say in. Because the Innu had originally welcomed a permanent French presence in the area (both to facilitate trade and to act as a buffer against Haudenosaunee raiders coming from the south) and because the French hadn’t yet displaced anyone by building out their Quebec trading operations, all of the hard questions about who owned (or controlled) which land were put off into the future.

All of which to say, the French were pursuing a two-faced policy—explicitly claiming Quebec as French territory in Europe, while pretending otherwise when seeking the favour of their Indigenous neighbours. It was only a matter of time before this contradiction came out into the open and an Indigenous group began questioning French motives. For the reasons described above, that group happened to be the Innu, who began to see Champlain’s goal of resettling them as farmers in ominous terms.

Fuelling these anxieties was the fact that in the late 1610s and early 1620s, Europeans were beginning to create, as the expression goes, “facts on the ground.” The earliest French structures had been so shoddy that Indigenous trade partners (such as the venerable Mi’kmaq chief Membertou) struggled to prevent them from falling apart during the winters when Europeans were absent. But now, European masons and carpenters were starting to put up real permanent structures—including the religious buildings that the French naturally imagined would lie at the architectural heart of their new communities.

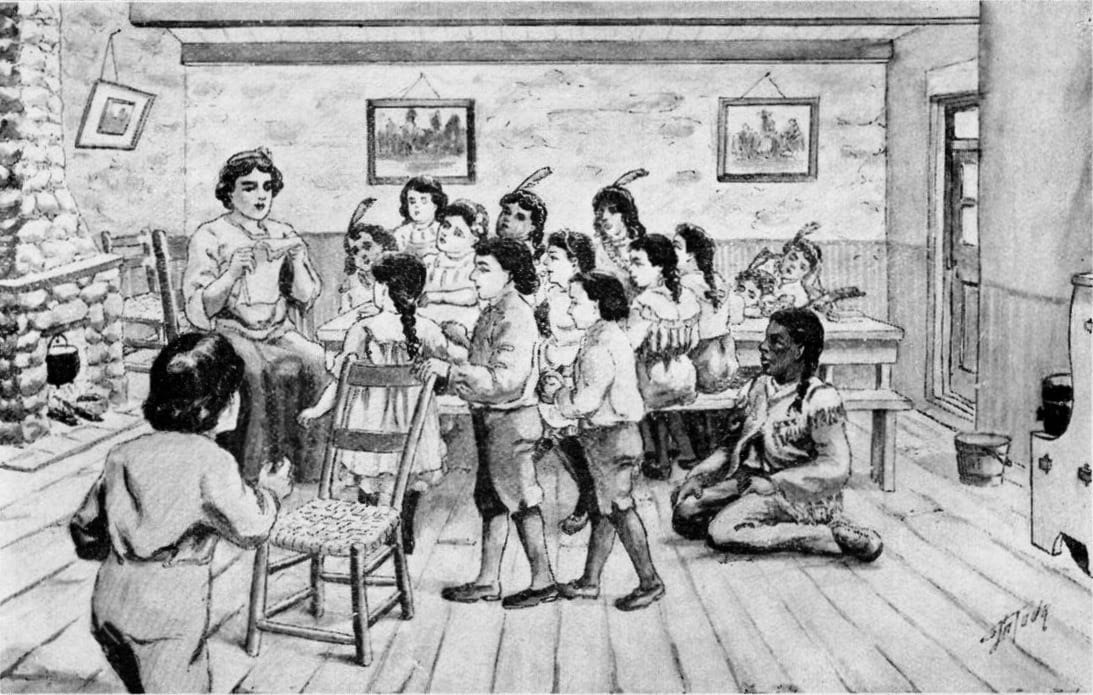

In 1615, the Récollets began work on a seminary and monastery on the St. Charles River, which flows east through Quebec City before entering the St. Lawrence at what is now the Port of Quebec. The original goal had been to draw in young Indigenous boys and give them a Christian education. As the Récollet presence in Canada grew, however, the site became an all-purpose focal point for religious life.

Quebec’s agricultural base also started to take shape. A man named Louis Hébert (1575–1627)—a veteran of the failed Acadian expeditions—is remembered as Quebec’s first farmer (as well as its first apothecary). And the deal he secured from Champlain would become a model for future migrants: In return for Hébert moving to Quebec with his family and serving as the colony’s medical expert, the Company would pay him a generous salary and (after three years) provide him with a plot of land to farm. Large-scale land clearance and farming (as well as the emergence of the seigneurie system that every Quebec student learns about in middle-school history classes) would depend on greater investments from the French state than would be forthcoming for many years. But the basic process of turning Quebec from a trading post into an offshore French farming colony had begun.

In 1618, Champlain—who was not otherwise one for grandiose pronouncements—produced a manifesto that laid out a rosy vision of New France’s future. He argued for a diversified economy, projecting immense profits from fisheries, lumber, mines, and livestock farming, in addition to the continuation of the fur trade.

In reality, Quebec was poorly placed to play a leading role in the Canadian fish trade, which would always be dominated by Newfoundland and the mainland Maritime region (for oceanographic reasons that need not detain us). And estimating the value of any minerals in the area was pure guesswork. But in the winter of 1618–1619 Champlain was back in France, promoting these talking points, even as Condé, his most influential patron, remained in prison. Whatever political suspicions hung over Champlain, his pitch was enough to win over France’s commercial elite and, most importantly, the young King, Louis XIII (who by now had exiled his mother and executed her leading followers, Concini included).

The Crown authorised the Company to oversee the migration of 300 families over the next five years, an aspirational number that allowed Champlain to imagine the creation of three more settlements on the St. Lawrence, in addition to the original colony at Quebec. Wendat and Algonquin traders had been particularly eager for the French to set up a permanent settlement at the great rapids, near the spot where the Ottawa River empties into the St. Lawrence—effectively marking the location of modern Montreal.

Champlain’s report assured the French court that this upfront investment of resources would be quickly recouped, with tax revenue growing no less than ten-fold over the next decade. While it would be private investors, not the Crown itself, that would be providing this upfront capital, Louis’ blessing was crucial, for it signalled to one and all that Champlain would retain the monopoly commercial rights on which the health of his balance sheet depended.

And yet, in the Spring of 1619, just a few weeks after the King authorised Champlain’s new plan, Champlain’s own corporate partners rejected it. To drive the point home, they stripped Champlain of his administrative role within the Company, and demoted him to the status of mere explorer—his original role when he’d first sailed to Quebec in 1603.

This power struggle within the Company—which, ironically, was taking place when Champlain seemed set to deliver on his most ambitious promises—resulted from the continued imprisonment of the Prince of Condé, who still remained Viceroy of New France. Without a politically powerful leader (who wasn’t isolated in the Bastille), the colonial project had descended into infighting. Champlain was forced to cancel his plans to return to Canada, and stayed in France for all of 1619 and into 1620, until matters could be sorted out.

The first step to bringing order to New France would be to find a viceroy who was free to govern. While Condé would eventually be released from prison (along with his wife, who’d joined him behind bars in a show of solidarity), he’d transitioned from political asset to liability. And as part of his reconciliation with his enemies at court, Condé agreed to sell his colonial viceroy office to his brother-in-law, the Duke of Montmorency. Like Condé, Montmorency was a powerful noble who knew his way around the halls of power. But unlike Condé, he didn’t have a history of insurrection.

Like the King, Montmorency was impressed with Champlain’s ambitious plans for New France, and sided with him in the Company’s internal debates. But he also wanted to restructure the Company’s trade monopoly as a partnership between Ezechiel de Caën (a well-connected merchant out of Rouen) and his nephew Guillaume de Caën. The larger Caen family oversaw a commercial network that spanned Normandy, and which had long been involved in trans-Atlantic trade. Unfortunately, while Ezechiel was Catholic, Guillaume (who would be more directly involved in the colony’s operations) was a Huguenot—somewhat complicating life for those, such as Champlain, seeking to keep the Récollets happy.

The Compagnie de Caën (as the new group would be known), was given an eleven-year monopoly on the Canadian fur trade, on condition that it settle at least six families per year on the St. Lawrence, as well as support a small group of missionaries in the area. This colonisation effort fell far short of what Champlain had proposed, but it was a victory of sorts for him, as the new regime elevated him to the office of Lieutenant-General—effectively re-establishing him as the top man on the ground in Quebec.

Once back in Quebec in Spring 1620, Champlain helped the Récollets lay the foundations of the stone church that would replace the wooden structure they’d erected on the St. Charles River. Champlain also decided it was time to rebuild Quebec’s original Habitation, a rickety 1608 structure that had been adequate for seasonal traders, but not for permanent residents.

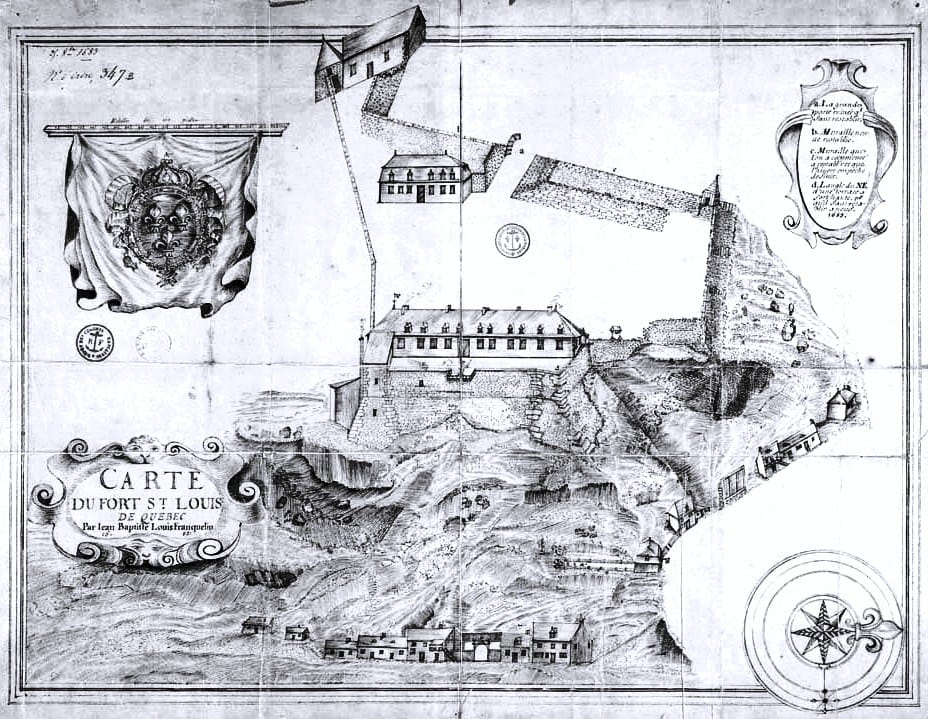

Work also began on a fort, named Saint-Louis, which would dominate the high ground overlooking the St. Lawrence River. It sat on Cap Diamant—Cape Diamond in English. And if you’ve ever visited Quebec City, you’ll know this as the same cape that British troops would climb in 1759 before their decisive engagement with the French on the Plains of Abraham.

But in 1620, it wasn’t the British whom Champlain was readying himself against, but fellow Frenchmen. That’s because umbraged stakeholders in the old Company that had been replaced by the Compagnie de Caën had challenged the legitimacy of the new operation in French courts. And Champlain worried that these men would also try to press their case by force through gunboat diplomacy.

That winter, Quebec would house sixty men, its highest population yet. As always, however, it was a struggle. The settlement scratched out an existence over the frigid winter months, and was nearing the end of its rations by the time supply ships from home were due to arrive. As Champlain feared, these first ships that arrived in 1621 were affiliated with the old Company. Fortunately, however, cooler heads prevailed. Despite their corporate rivalry, the ships generously supplied the Frenchmen at Quebec—in part because their fleet was led by Champlain’s old comrade, Pont-Gravé.

A few weeks later, Guillaume de Caën arrived with his own trading fleet, and announced that the King had decreed a temporary compromise: For the current season, both Companies would be allowed to trade. This news didn’t entirely defuse the tensions (and at one point, de Caën personally seized one of Pont-Gravé’s ships), but all-out war was prevented.

Amid this period of uncertainty, the Récollets aired some of their grievances. The obvious one was that, as they saw it, the Huguenot presence within the Company’s leadership was unacceptable—up to and including Guillaume, who led the Protestant branch of his clan.

Especially troubling to these Catholic missionaries was de Caën’s attempt to establish a farming community on Cap Tourmente, about 40 kilometres downriver from Quebec (now a national wildlife area). If Huguenot settlers arrived in Canada, it would be difficult to remove them, or restrict their worship, as they’d be operating under the protection of the aforementioned Edict of Nantes.

And Champlain himself was offering his own grievances—an unusual rebellious gesture for someone who was far more used to mollifying complaints than announcing them. Six families, he said, were hardly enough to form a real colony.

In August 1621, Champlain chaired a group of Quebec’s residents with the goal of petitioning the King so as to “advise on the most appropriate remedies against the ruin and desolation of this whole country.” This ad hoc “assembly” was really just a handful of merchants and artisans. But insofar as it arrogated to itself the status of a Quebec-based political body articulating Quebec-based political interests, it represented something of a landmark in French-Canadian history.

The assembly produced a document that reflected the interests of both Champlain and the missionaries, suggesting that their shared geographic ties were now at least as important as their (divergent) professional objectives. More resources had to be directed to colonisation and missionary work alike; Protestants had to be banned from the colony; and the Lieutenant-General of New France (Champlain) had to be given greater authority to make decisions. More than a century and a half before America’s Declaration of Independence, the question of how powers were to be divided between home country and local colonists was asserting itself, albeit in fledgling form.

In the Spring of 1622, France’s royal council arrived at a compromise solution. The old company would be cashed out for the three years remaining on its monopoly, and its partners would be given an opportunity to buy into an expanded version of the Compagnie de Caën (which would still be led by the de Caëns). The Crown also placed restrictions on Huguenot traders in Canada, prioritising the Catholic mission of the colony in a manner that it hoped would satisfy the Récollets.

Champlain’s dream of a large-scale colonial influx would have to wait, though. There was still little appetite in France for such a costly enterprise.

Nevertheless, thanks to regular convoys of fur coming down the Ottawa River every summer, the colony was on secure commercial footing. Through their religious allies, the Récollet missionaries were opening up new avenues of political support and financial investment. And with the colony no longer led by an imprisoned viceroy embroiled in a quasi-civil war at court, Champlain had reason to hope that he’d no longer be buffeted by the vagaries of French politics. Going into 1622, it seemed, he had all his ducks in a row.

Which was a good timing, because soon, a new kind of challenge would be emerging—for the French weren’t the only Europeans seeking to profit from the bounty that North America had to offer. Down at the mouth of the Hudson River, near modern-day New York City and Albany, the Dutch were building their own Indigenous alliances to counter the power of the Laurentian Coalition. And in our next instalment, we’ll check in with them to see how they’re faring.