French History

France’s Founding Fathers: A Review of ‘House of Lilies’

In a new book, Justine Firnhaber-Baker tells the story of the Capetian dynasty (987–1328), whose rulers stitched a set of medieval duchies and counties into a single kingdom.

I’m a PhD medievalist, but the history of medieval French royalty was never my specialty, and my ignorance was vast.

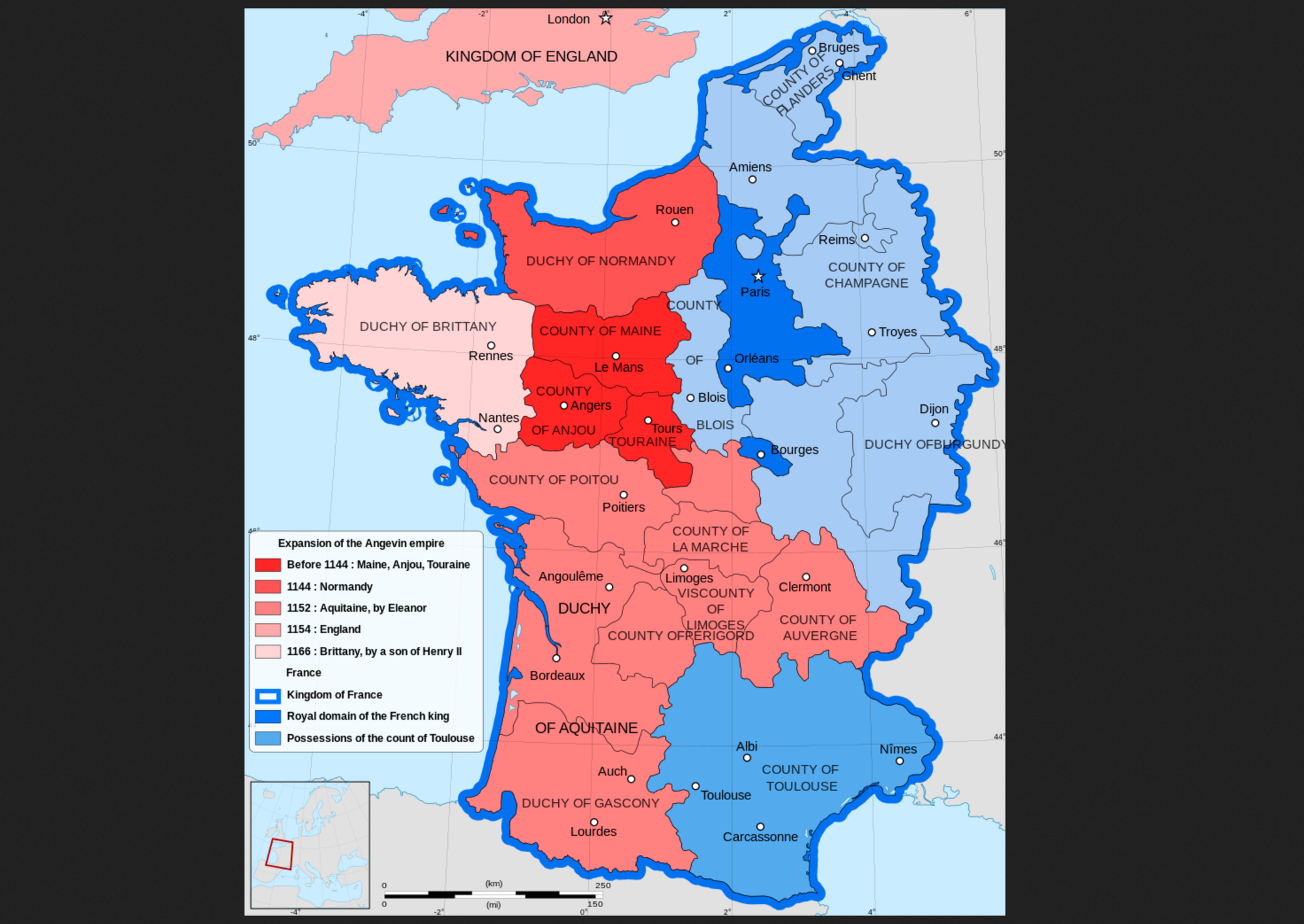

I’d assumed, for example, that the French kings of the Middle Ages were mostly fainéants whose writ scarcely ran past the Île-de-France region (encompassing the city of Paris and its environs). The English monarchy across the Channel had been centralised since the days of Alfred the Great (849–899); but the French kings seemed to rule in a more symbolic capacity, being perpetually at the mercy of the powerful dukes and counts of autonomous French regions such as Normandy, Burgundy, Aquitaine, Anjou, Blois, Toulouse, and Languedoc. These regional rulers were technically royal vassals. But, in actuality, they saw themselves as absolute rulers in their own right, and so had no compunction against turning on the crown when they thought it would further their interests.

My impressions had been formed by accounts of the 17-year-old Joan of Arc’s having to personally drag the Dauphin (the future King Charles VII) to Reims for his coronation in 1429, and by Shakespeare’s historical plays, which portrayed the French as fops incapable of defending their territory against the robust and brotherly English during the Hundred Years’ War. Indeed, the whole point of that war (from the English perspective) was that, by dynastic right, large portions of France’s fractured political landscape actually belonged to England.

The one medieval French royal (by marriage) I did know something about, Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122–1204), dumped her French husband, King Louis VII (1120–1180) after he bungled the Second Crusade, a costly and embarrassing adventure on which Eleanor had accompanied him on horseback. (“Never take your wife on a Crusade,” a medievalist friend of mine once sensibly quipped). To top off his disastrous final loss of his Crusader army in 1148 during an ill-considered attack on Damascus—which, although Muslim-ruled, was in fact an ally of Latin-Christian Jerusalem—Louis and Eleanor had failed to produce a son. No sooner was the ink dry on their divorce in 1152 (technically an annulment, since the two were Catholics), than she married Henry Plantagenet, son and heir of the duke of Anjou, who two years later became King Henry II of England. Henry quickly procreated five sons (among fourteen surviving children) with his new bride. Thus began the dynasty that would rule England for more than three centuries.

As everyone who has seen The Lion in Winter knows, Henry II’s relationship with Eleanor was far from tranquil, but two of their sons succeeded him to the English throne: Richard the Lionheart and King John (of Magna Carta fame or infamy, depending on your perspective). Henry was, besides king of England, duke of Normandy and count of Anjou, through his great-grandfather, William the Conqueror, and his mother, Matilda, who’d married Henry’s Anjevin father, Geoffrey, after her first husband, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, died in 1125.

Eleanor’s grounds for annulling her marriage to Louis had been that he was her fourth cousin, which violated the Catholic Church’s (selectively applied) consanguinity restrictions. But Henry was even closer kin, being her third cousin. The humiliated and (understandably) rankled Louis demanded that Henry, as his feudal vassal, explain why he’d failed to ask permission to marry (let alone marry his boss’s ex). Henry declined to reply, the feudal equivalent of declaring oneself in rebellion. Louis retaliated by invading Normandy—unsuccessfully—and trying to hold onto Eleanor’s Aquitaine on the claim that he’d become its duke by marriage (Henry II was meanwhile making the same claim) before giving up and remarrying himself in 1154.

I’d assumed that French kings wouldn’t hold much in the way of real royal power until the time of King Louis XIV (1638–1715), who declared (perhaps apocryphally), L’État, c’est moi, and forced French regional nobles to reside in his over-the-top palace at Versailles (where they’d dissipate their incomes via elaborate court ceremonies instead of making trouble from their provincial power bases).

But the scales have now been knocked from my eyes, thanks to Justine Firnhaber-Baker, a professor of French medieval history at the University of St Andrews. The subtitle of her new book, House of Lilies: The Dynasty That Made Medieval France, refers to the Capetian dynasty founded by Hugh Capet (c. 940–996), who took his royal title in 987 A.D. Every French monarch, from Hugh’s reign to the French Revolution and beyond, had Capetian blood running through his veins—including the aforementioned Louis VII, who was a direct descendant of Hugh, and the bookish, dithering King Louis XVI, who was not, but who nevertheless went to the guillotine in 1793 under the derisive sobriquet “Citizen Louis Capet.”

In fact, from 987 to 1328—the death year of King Charles IV, Hugh’s great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandson—every single king of France didn’t just boast Capetian blood, but was the biological son of a preceding French king. This stretch of eleven generations (some of the Capetians succeeded their older brothers) and more than 300 years of father-to-son succession was astounding given the high infant and childhood mortality rate of the Middle Ages.

It helped that medieval monarchs could draw on multiple successive queens to give them male heirs, since women frequently died in childbirth, and kings had the clout to persuade or bully bishops and popes into granting them annulments that were normally unavailable to ordinary people. (Even Louis VII—about whom Eleanor had complained, “I married a monk”—finally did produce a son in his middle age, by a third wife in 1160; the youth took the throne as King Philip II on his father’s death and reigned until his own death in 1223.)

Furthermore, the Capetians, far from being kings in name only—as I had incorrectly surmised—actually built the country we now know as France, wrestling it into a nation by dint of warfare, strategic marriages, and delicate political negotiations with the powerful regional princes who’d controlled most of its territory quasi-independently. As Firnhaber-Baker writes,

By 1300, Capetian France was not only the most powerful kingdom in Christendom but also the most prestigious.... It was they who transformed muddy Paris into a splendid metropole and they who are responsible for some of the city’s most cherished tourist attractions, including the Sainte-Chapelle and the Louvre.

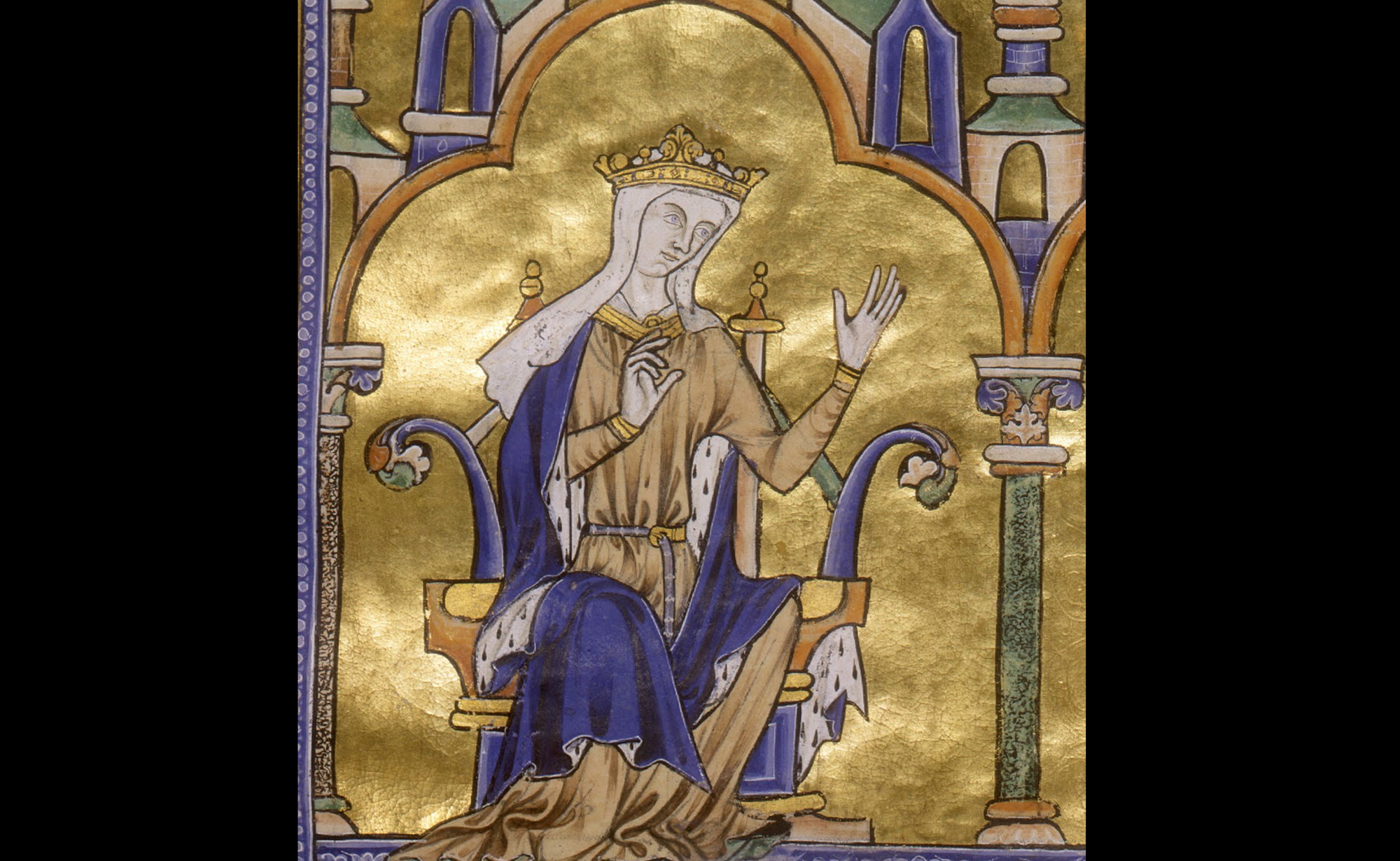

Louis VII’s father, King Louis VI (1081–1137), nicknamed “Louis the Fat” because he could scarcely get onto his horse, began to use the fleur-de-lys, the stylised three-petaled lily, as a symbol of his royal house. Associated with the Virgin Mary, the lily became a powerful emblem of his dynasty, signifying, as Firnhaber-Baker points out, the blessing of heaven upon the dynasty’s claim to the throne.

Firnhaber-Baker’s otherwise wonderful book, if anything, might be critiqued for passing too lightly over the monumental cultural achievements of medieval France under its three centuries of Capetian rule: Gothic architecture, which the Capetian abbot Suger invented nearly singlehandedly; the courtly-love poetry of French troubadours; chivalric literature from the Song of Roland to artfully wrought tales of King Arthur’s court; polyphonic music; scholastic philosophy; and even tailored clothing cut and sewn to fit and flatter the body instead of the stitched-together rectangles of cloth that had hitherto prevailed. The medieval French invented French couture. A sixteen-page insert of colour plates in Firnhaber-Baker’s book displays a panoply of sumptuous Capetian-era artefacts: stained-glass windows, manuscript illustrations rich with gilding, stone statuary, finely fashioned gold vessels.

House of Lilies, with its focus on the deeds and personalities of the Capetian kings, represents a refreshing throwback of sorts to the Great Man theory of history—according to which history’s protagonists are seen as guiding and defining their cultures rather than simply reflecting them. For decades (thanks in no small part to France’s own Marxists), many academic historians have preferred to write “social history” that emphasises the ways of lower-caste people, and which teases out their attitudes toward the world around them. All of this is interesting. And it’s entertaining to read a book such as ur-social historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie’s Montaillou, village occitan de 1294 à 1324 (1975), about Capetian-era Cathar heretics in the Pyrenees picking lice off each other and having sex with the village priest. But what many of these medieval people themselves were often really interested in, as evidenced by the numerous monastic and lay chroniclers who comprise Firnhaber-Baker’s principal primary sources, was the extravagant lifestyles and life stories of the rich and famous—that is, kings, queens, and the high nobility.

The chroniclers, in the fashion of ancient historians such as Suetonius and Dio Cassius, loved juicy tales about celebrities (sometimes true and sometimes not) as much as moderns do, and they retold them with gusto—especially if the tales (which Firnhaber-Baker does her best to evaluate critically) involved, as they almost invariably did, the eternal fodder of soap opera: tangled relations with wives, lovers, offspring, and kin.

The Capetian kings might not have been “great men” in the classically Napoleonic sense, but they made the history—military, political, religious, and cultural—of medieval France. Their female counterparts were mostly traded around like brood mares, valued mostly for their looks, their pedigrees, their potential fertility, and their function as glue for political alliances—yet a surprising number of Capetian queens were formidable presences in the lives of their men as regents, queen mothers, and occasional co-rulers.

When the dynasty’s founding father, Hugh Capet, assumed the throne in the late tenth century, there was, in fact, no such country as “France.” There was only an entity called “West Francia,” the western segment of Charlemagne’s Frankish empire, which had been divided among his three royal grandsons—with the eastern segment, corresponding to today’s Germany and its environs, eventually becoming the Holy Roman Empire. (There was also no such family known as “Capet.” Firnhaber-Baker traces the invented name to the French word for cloak, referring to the founding monarch as “Hugh of the Short Cloak.” Another theory has “Capet” as deriving from a Latin word, caput, meaning head.)

Hugh belonged to a Frankish family that modern historians call the Robertians after their ancestor, Robert the Strong (c.830–866), a powerful nobleman in the court of Charlemagne’s grandson, King Charles the Bald, the first ruler of West Francia. Robert’s younger son, another Robert, managed to depose Charles’s grandson, King Charles the Simple, in 922 A.D., and become king himself. After that, the West Frankish throne bounced between the Robertians and the descendants of Charlemagne who followed what historians refer to as the “Carolingian” line.

Hugh Capet, who was the younger Robert’s grandson, got himself unanimously elected king of the Franks at an assembly of nobles and bishops, more or less as a compromise candidate, despite his near-lack of any hereditary claim to the throne, after waging war successfully against some of the Carolingians. He’d also snagged the patronage of Adalbero, archbishop of Reims, who argued to the assembly that “[a] man’s wisdom, loyalty, and greatness of spirit should count as much as his lineage” (and that the Carolingian contender, Duke Charles of Lorraine, was unworthy by the same logic).

Hugh’s royal descendants were a mixed bag of traits and temperaments. His son, King Robert II (c. 972–1031), got the nickname “the Pious” because of his ascetic practices, his almsgiving, and his reputed ability to heal the sick and give sight to the blind by signing the cross over them. When he was laid to rest at the abbey of Saint-Denis north of Paris, where nearly all French monarchs had their tombs, the roadways were lined with mourners drawn from among the poor and the lame, as well as widows and orphans. (Robert was also the first French king—and not the last, alas—to order the burning of Christian heretics and the persecution of Jews.)

By contrast, Robert’s libertine grandson, King Philip I (c. 1052–1108), would be excommunicated from the Church no fewer than three times, thanks to his midlife infatuation with Bertrada, wife of Fulk IV (also known as Fulk le Réchin, typically translated as Fulk the Rude), count of Anjou. The two eloped at the first available moment, even though Philip was already married—to Berthe of Holland (Louis the Fat’s mother). And running off with Bertrada endangered his diplomatic relations with Berthe’s stepfather, the count of Flanders, not to mention the goodwill of Anjou, erstwhile a counterweight ally against English claims to Normandy. Philip couldn’t persuade the French bishops, much less the pope, Urban II, to let him divorce Berthe. But he married Bertrada anyway, in 1092, cementing his religious disgrace. As a result of Urban’s papal interdict, Mass couldn’t be said anywhere in France, and church bells couldn’t ring. The excommunication also meant that Philip had to miss out on the First (and only successful) Crusade, called by Urban in 1096 with the goal of conquering Jerusalem for the Latin West.

A century later, the contrast between the hapless Louis VII of the (failed) Second Crusade and his late-born son, Philip II, was even more striking. Philip, nicknamed “Augustus,” had, unlike his father, a will of iron and a heart made of ice. He devoted nearly his entire reign to crushing his enemies on the battlefield, in the law courts, and via a strategy of setting them against each other.

At the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, he won a decisive victory against a Plantagenet-allied army led by the soon-to-be deposed Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV. Philip rode into battle blazoned with fleurs-de-lys, and his troops advanced under a streaming orange-red standard, known as the Oriflamme, which was said to have been raised by Charlemagne himself. The Plantagenet King John, holed up in northern France, had to slink back minus his family lands to England, where his barons confronted him the next year at Runnymede—a meeting that would eventually yield Magna Carta. While Otto escaped, Philip had the counts of Flanders and Boulogne, who’d sided with John, loaded with chains and immured in his darkest dungeons, one of them inside his newly constructed castle in Paris, the Louvre.

Philip Augustus was just as savage to his wives. He tried to get rid of his first wife, Elizabeth of Hainaut, whom he’d married in 1180, shortly after taking the throne. But she was a sympathetic figure—just 10 years old when married, and just 14 when cast out by her royal husband. Elizabeth fought back by making herself a people’s queen, walking barefoot to church and praying loudly for God and bystanders to save her from her husband’s wrath. Philip relented. And in 1187 she gave birth to a son who’d eventually become King Louis VIII (d. 1226). She died in childbirth less than three years later.

With his second wife—the extraordinarily beautiful 18-year-old Danish princess Ingeborg, sister of the king of Denmark—Philip behaved even worse. The backstory here is odd and contested: On their wedding night in August 1193, Philip somehow found himself repulsed by Ingeborg, and he promptly sought an annulment on grounds of non-consummation—specifically, impotence caused by sorcery. When the queen insisted that she had indeed been maritally deflowered, Philip maintained that nonetheless he had not ejaculated. Two successive popes refused to give him the annulment he wanted, so he imprisoned Ingeborg in various castles for nearly 20 years and married another woman, Agnes of Méran, in 1196. After Agnes died, in childbirth like Elizabeth, Philip and Ingeborg more or less reconciled, if only so Philip could be free of the interdict slapped onto France by Pope Innocent III and have his two children by Agnes declared legitimate.

By the time Philip Augustus died in 1223, the French Crown was Europe’s wealthiest, thanks in part to Philip’s territorial expansions at the expense of the (now principally English-based) Plantagenets, and in part to the Medieval Warm Period, which helped increase France’s agricultural productivity and general prosperity. Philip devoted his treasury to a grand reconstruction of Paris, the fruits of which mark tourist itineraries to this day. His building projects included not only the Louvre, but also the Les Halles market (which stood on lands belonging to the Jews whom he’d expelled from the city in 1182), the University of Paris, and a good chunk of the Notre Dame Cathedral, on which his father, Louis VII, had broken ground two years before his death.

In the wake of Philip Augustus’s sins, France was ready for a certified saint to take his place. And it would eventually get one, in the form of his grandson King Louis IX (1214–1270)—Saint Louis, namesake of the Missouri metropolis and dozens of other cities around the world where the French would claim influence in later centuries.

Louis’s father, Louis VIII, had reigned for only three years, in time to launch the Albigensian Crusade against France’s own fanatical Cathars, before dying of dysentery in 1226 and leaving twelve-year-old Louis under the regency of his daunting mother, Blanche of Castile. Blanche co-ruled with Louis until he turned twenty, and after that meddled with his reign where she could. This included efforts to keep him apart from his wife, Marguerite of Provence. (They had to sneak around to arrange their romantic assignations.)

Louis cherished all that was holy. In 1239, he received from Constantinople a precious relic, Christ’s Crown of Thorns, miraculously preserved in evergreen through the centuries (or so it was supposed). He built the gloriously Gothic royal chapel known as Sainte-Chapelle on the Île de la Cité to house the Crown (it was moved to the nearby Notre Dame during the Revolution, where it equally miraculously survived the 2019 fire). Louis also instituted even stricter anti-Jewish policies than Philip Augustus had—banning the interest due them on their loans and restricting their movements. In 1240, he instigated a “Trial of the Talmud,” over passages in the central text of Rabbinic Judaism that were alleged to contain scurrilous references to Jesus. The Talmud was sentenced to destruction, and every copy in northern France was seized, carted to Paris, and burned. Even Louis’s counsellors thought he had gone too far, especially with the usury ban; as French businesses depended on financing from Jewish lenders.

In 1248, Louis went on a Crusade (the Seventh) that proved even more disastrous than his namesake great-grandfather’s (and, like his great-grandfather, he took his wife). The aim was to reclaim the Holy Land by attacking through Egypt, then the leading Middle Eastern Muslim military power. As recounted in one of Firnhaber-Baker’s most vividly rendered chapters, Louis lost two-thirds of his men in Egypt to disease, gangrene, and superior enemy tactics. The French king himself was captured, and Marguerite, exhausted, terrified, and pregnant, had to raise a backbreaking ransom.

When he returned to France in 1254, Louis cast his humiliating defeat as punishment for his sins, and began pursuing sanctity in earnest. He set up tables to feed the poor in his palaces and founded hospitals, asylums for the blind, and homes for reformed prostitutes. He issued a grande ordonnance aimed at eliminating official corruption, and established a formal court, the parlement, which established uniform standards for procedural justice, as well as banning dicing, blasphemy, and a range of other moral offences.

He infuriated the French nobles by interfering with what they considered their special privileges. For example, Firnhaber-Baker writes, after the Lord of Coucy hanged three boys caught poaching rabbits from his lordship’s forest in Picardy, Louis threw the noble into the Louvre. (He wanted to hang the man, but was persuaded to mete out a less drastic punishment following the importuning of other nobles.) That kind of gesture, as one might imagine, made Louis exceedingly popular with ordinary people—who could spot him walking barefoot along the muddy streets of Paris handing alms to paupers, sometimes with his children alongside, while his confessor beat him with a chain.

In March 1270, as a further penance, Louis set sail on an Eighth Crusade, this time to Tunis, where he apparently hoped to convert the emir to Christianity. By August, however, Louis was dead, probably of dysentery or some other intestinal ailment that had swept through the crusaders’ North African camp. The Crusade was over, but the veneration of “Saint Louis” as a model Christian monarch had just begun. Witnesses attested to some 67 healings at his tomb at Saint-Denis, and Pope Boniface VIII officially canonised him in 1297.

When the Capetian dynastic edifice did start to crack, it collapsed quickly. Louis’ son and successor, King Philip III (1245–1285), was a mediocrity. “No one could argue that he was an impressive man or an effective king,” Firnhaber-Baker writes. Part of Philip’s problem, besides his being none too bright, was that while France had been boomingly prosperous during his father’s reign, well-fed, and at peace (at least in regard to the domestic front), the Medieval Warm Period (as we now understand it) was winding down and winter was coming. France was broke.

Next in line, following his early death, was his 17-year-old son, King Philip IV (1268–1314), nicknamed “the Fair” (le bel) because of his unusually good looks. He was perhaps the coldest fish ever to sit on France’s throne (Emmanuel Macron doesn’t count). “Humorless, stubborn, aggressive, and vindictive” was how one modern historian described him. One of his obsessions was squeezing revenue from whatever sources he could find to fund a series of wars against his real and imagined enemies: imposing onerous new taxes, even on the Church’s clerics, who were technically off-limits; devaluing the coinage; expelling the Jews (again) so he could expropriate their property.

He also declared war on a new arch-foe, Pope Boniface VIII (over a bull from Boniface claiming to exercise feudal suzerainty over European monarchs), to the point of charging Boniface with heresy, sodomy, and—this one seems a stretch—keeping a pet demon. Boniface died in 1303, and Philip was then able to help install a more compliant pope, Clement V, a Frenchman as it happened, who moved the papal residence to Avignon in 1309.

Philip the Fair’s most well-known achievement (if that’s the right word) was his suppression of the Knights Templar, which he did, starting in 1307, by having every Templar found in France arrested and tortured. With some assistance from Clement, he had dozens of them burned at the stake for heresy, including their aged Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, in 1314. (The reason wasn’t—sorry, Da Vinci Code fans—that the Templars were protecting the secret offspring of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, but that they’d long acted as bankers to the French crown and nobility, and Philip had been hoping to keep their reserves for himself once he’d convinced Clement to declare the order dissolved.) Molay was said to have put a curse on Philip and Clement before he expired; and, sure enough, both were dead within the year.

But not before Philip heard a report—from his daughter Isabelle, who was married to King Edward II of England—that the wives of two of his sons—Louis, the royal heir presumptive, and Louis’ younger brother, Charles—had been carrying on adulterously with a pair of brothers from the minor nobility. Philip’s agents burst into the nunnery where the two young women, Marguerite and Blanche, were staying and arrested them. They had their heads shaved, and were stripped of their royal robes, clothed in “vile rags,” and shipped off to a grim Norman castle for life. (A third royal wife, Joan, wife of Philip’s middle surviving son, Philip, was also imprisoned, although she was never specifically charged with any crime.) As for the two brothers accused of sleeping with King Philip’s daughters-in-law, they were skinned alive, castrated, and decapitated, all in public, with their heads displayed next to their headless bodies on the gallows. The king seemed to relish the spectacle; he “seemingly stayed to watch,” a historian quoted by Firnhaber-Baker writes.

If all this reminds you of Game of Thrones, with Philip the Fair bearing a suspicious resemblance to Tywin Lannister, it should. The French writer Maurice Druon (1918–2009) turned the saga of Philip and his descendants into a series of lurid historical novels, Les Rois maudits (“The Accursed Kings,” 1955–1977) that in turn inspired J.R.R. Martin’s R-rated sword-and-sorcery franchise.

After the Tour de Nesle affair (named after the guard tower in Paris where the adulterous meetings were supposed to have occurred), it was downhill, morally, politically, and procreationally, for the Capetians.

The 24-year-old Louis, who was already king of Navarre in the Basque country on his mother’s side, succeeded his father as King Louis X. He lasted less than two years on the French throne before fatally collapsing after a tennis game (there were rumours of poisoning). Marguerite had died soon after her imprisonment, and Louis had quickly taken a second wife, Clémence of Hungary. She was pregnant at the time of his death. The baby was immediately hailed as King John I—but he died five days after his birth.

This caused a sort of constitutional crisis, because Louis was the first Capetian in three hundred years to die without leaving a son. He did leave a four-year-old daughter: Joan, by Marguerite, who was later to rule her grandmother’s kingdom in Navarre. She was theoretically next in line for the French throne after her half-brother’s death—except that Louis’s brother Philip, who had already manoeuvred himself into royal power by acting as John’s regent, had himself crowned King Philip V at Reims in 1317, citing what was supposed to be an ancient Salic law that barred female succession.

Philip wasn’t a bad king overall, but the legal claims he’d made came back to bite him and his family: He died in 1322, leaving only daughters, four of them. (His one son, born shortly before his coronation, had died a month afterwards.) Philip’s younger brother, Charles, who succeeded him, produced two sons, but both died young. Only one of Charles’ four daughters survived to adulthood, and she died childless. That was the end of the House of Capet.

The kingship of France passed to Charles’ cousin, Philip, the count of Valois, King Philip IV’s nephew; he became King Philip VI (1293–1350). Meanwhile, Philip IV’s daughter Isabelle, who survived her brother Charles by thirty years, was making nothing but trouble. Her marriage to Edward II of England had turned sour around 1325, presumably due (in part, at least) to her husband’s recurring homoerotic infatuations with young men.

During a prolonged visit to her French relatives, she refused to return to England. Instead, she joined forces with the Marcher earl Roger Mortimer, exiled in France for fomenting rebellion against Edward over one of his romantic interests. The two put together an army and sailed to England in 1326, deposed Edward, and arranged for Isabelle to rule as regent for her teenage son, the future Edward III. Isabelle at some point became Mortimer’s mistress, and she and Mortimer may or may not have arranged for the murder of her husband, who died in captivity in 1327. In 1330, young Edward III reached age 18, whereupon he had Mortimer arrested, tried, and executed for treason. Isabelle got off pretty much scot-free and spent her last decades as a wealthy and respectable queen mum. Meanwhile, Edward, who, as Philip IV’s grandson, was actually a closer male relative of the Capetian kings than Philip of Valois, made a claim to the French crown and launched the Hundred Years’ War.

“The Capetian line didn’t end so much end as splinter,” Firnhaber-Baker concludes in her fine book. As Jacques de Molay is said to have hoped, the throne became cursed during this period. And France’s internal conflicts would go on for decades before the Valois line could solidly take root. Thanks to the Capetians, the prize in this game of thrones was not just Paris and its environs, as had been the case in the struggle for power won by Hugh Capet, but the vast bulk of the land that we know to this day as France.