Politics

Something Is Wrong

It is time for leftists to forego ideology and embrace a people-centred politics.

Something is seriously wrong with the Left today (or, at least, with large parts of the Left—I recognise that exceptions apply). Described abstractly, what’s wrong is the triumph of the ideological project and its slogans over the interests of people on the ground. Old leftists will remember Lenin’s distinction between revolutionary consciousness and trade-union consciousness—between militants who sought to create a communist society at any cost and workers who were looking for higher wages and a decent workplace. Or consider a much older but similar distinction in the biblical story of the exodus from Egypt—between the future priests hoping to raise up a “holy nation” and the ordinary Israelites dreaming of milk and honey. I want to reverse the values assigned to these two groups by the biblical writers and by Lenin. Leftists go badly wrong when they forget about milk and honey, about higher wages, and about the people on the ground.

Right now, this error is most clearly expressed by those left-wing militants who defend Hamas in the name of “resistance,” anti-colonialism, and liberation (or who imagine slaughter as a necessary means to liberation). They take this position without regard for the Israelis murdered on 7 October and without any serious interest in the people of Gaza. I know that many of the participants in the campus demonstrations are thinking of the hungry refugees, the shattered apartment buildings, and the rising count of dead and injured. But these concerns don’t determine the slogans the protesters shout or the politics those slogans promote.

As the protests continued, the government of Iran, Hamas’s chief supporter, was engaged in a brutal crackdown on Iranian women and girls seeking nothing more than minimal freedom. Here was a model of a future Palestine that the protesters didn’t dare look at. In truth, they didn’t want to think about the Palestinians who had lived for years under a brutally repressive Hamas regime, or about the women who would be subject to Islamist discipline in a fully developed Hamas state—let alone about the Jews who would be murdered or displaced if Hamas achieved its stated goal of annihilating Israel.

Even the Gazans suffering today—the necessary focus of any left-wing politics—are little more than emblems of Israeli cruelty in much leftist discourse. It is as if they have been conscripted for a political purpose: the elimination of the Jewish state. Leftist militants refuse to address Hamas’s military strategy of embedding its fighters and weapons in the civilian population. Nor will they acknowledge the extensive tunnel network Hamas has constructed beneath Gaza, in which its fighters shelter during Israeli bombardment but to which civilians are denied admittance. Nor is there much leftist interest in Palestinian wellbeing after the war or, more concretely, in how a regime of reconstruction might be organised in Gaza.

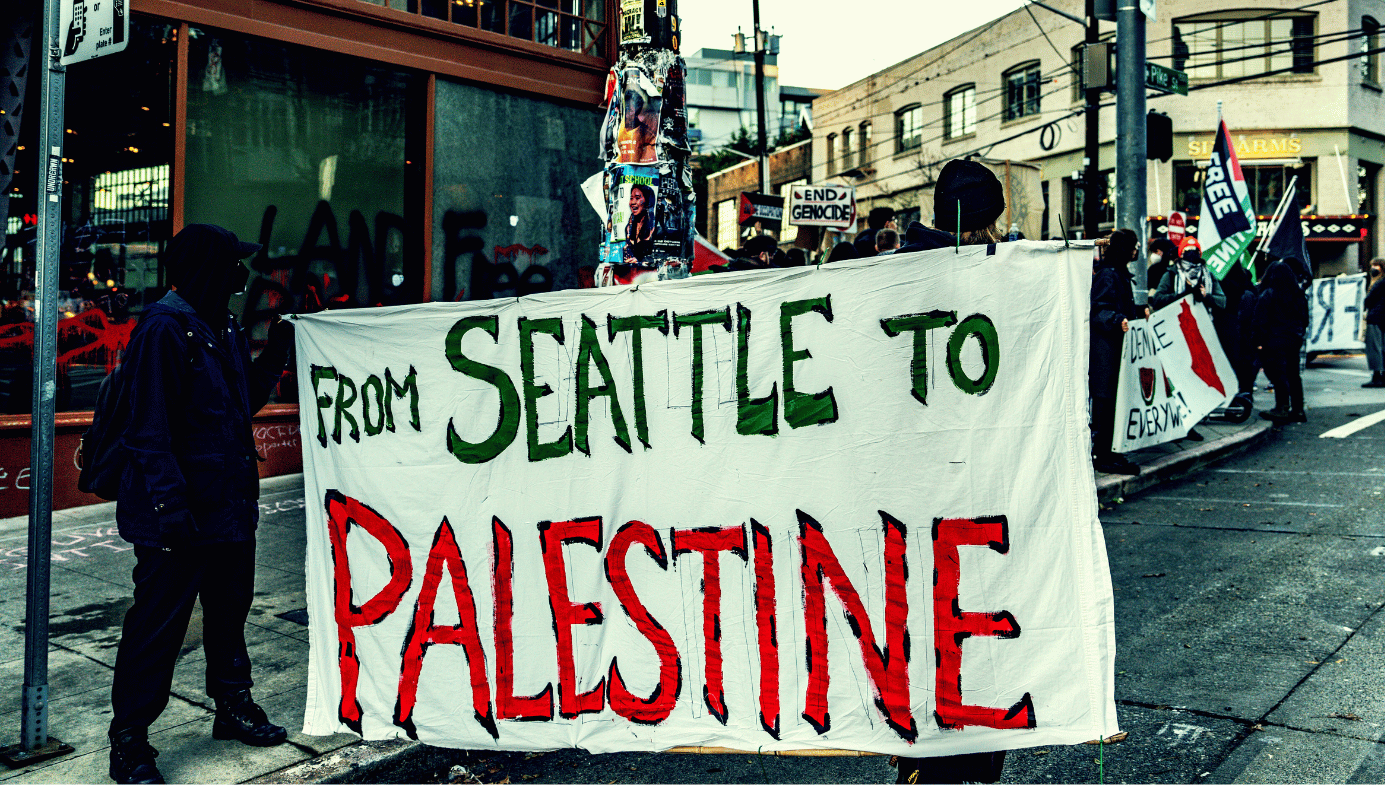

Not long after 7 October, when the Israeli counteroffensive was just beginning, Hamas supporters decided to bring the war home—perhaps in the belief that everything is finally determined here in the US, the great imperial power. The most readily available space for battle is the university campus, hence the protests that soon involved students and police in an ironic version of the class war (the students represent the bourgeoisie and the police officers are working class). Now the immediate issues are freedom of speech (for the protesters, but not necessarily for anyone else), financial divestment from companies doing business in Israel, and an end to all academic cooperation with Israeli universities. The goal is to turn Israel into a pariah state, isolated and alone.

The preeminent issue for American leftists is the American commitment to Israel and the ongoing supply of weapons. So, from the beginning, leftists demanded that a ceasefire be imposed by the US, assumed to be Israel’s puppet-master, and enforced by an immediate end to US military aid. That this would have meant a decisive victory for Hamas was rarely acknowledged, but that was surely the intention of those who organised the campaign. Perhaps they imagined a double victory: ending the Zionist project and furthering the decline of the American empire.

There is another war at home, directed not at American support for Israel but at American supporters of Israel—that is, at Zionists or at Jews assumed to be Zionists. This is mostly a matter of low-level harassment and exclusion not organised violence (yet), but it draws upon a long history of left-wing antisemitism, and it consumes a lot of the energy of the pro-Hamas Left. Though this hostility is ideological, directed at those considered privileged white supporters of Israeli settler-colonialism, it is also mindless—a kind of left-wing know-nothingism that begins by knowing nothing about the actual population of Israel. Intense ideological commitment often leads to a politics of focused hatred against enemies of the cause. I am old enough to remember Maoist propaganda campaigns against the “running dogs of imperialism.”

There are precedents for this triumph of ideological commitment over political engagement with ordinary people, and I want to look closely at one example in which I was personally involved. But first a question: Isn’t it strange to call this triumph “leftist”? Hasn’t it always been the purpose of the Left, and the honour of many leftists, to fight for the well-being of men and women in trouble; to build a mass movement that includes everyone willing to join? Sometimes, yes, but not always. Ideological radicalism and revolutionary wish-fulfilment have had an extraordinary hold on generations of leftists.

Leftists out of power often assume that leftists in power are ideologically faithful—that they live by the doctrines they proclaim. If the Soviet Union calls itself a “workers’ state,” and if factories are nationalised and farms collectivised, then almost nothing else matters—not starving Ukrainians, not dissidents sent to Siberian labour camps, not murdered Jewish writers and artists, not old revolutionaries brought to trial on trumped-up charges and shot. In fact, crimes like these can’t have happened. Any leftists who criticise the regime’s brutality are enemies of the workers—“social fascists,” as German social democrats were called during the 1930s in an early example of focused hatred.

The Hamasniks in America today are the descendants of those leftists who defended Stalinism. But they also have more recent American ancestors.

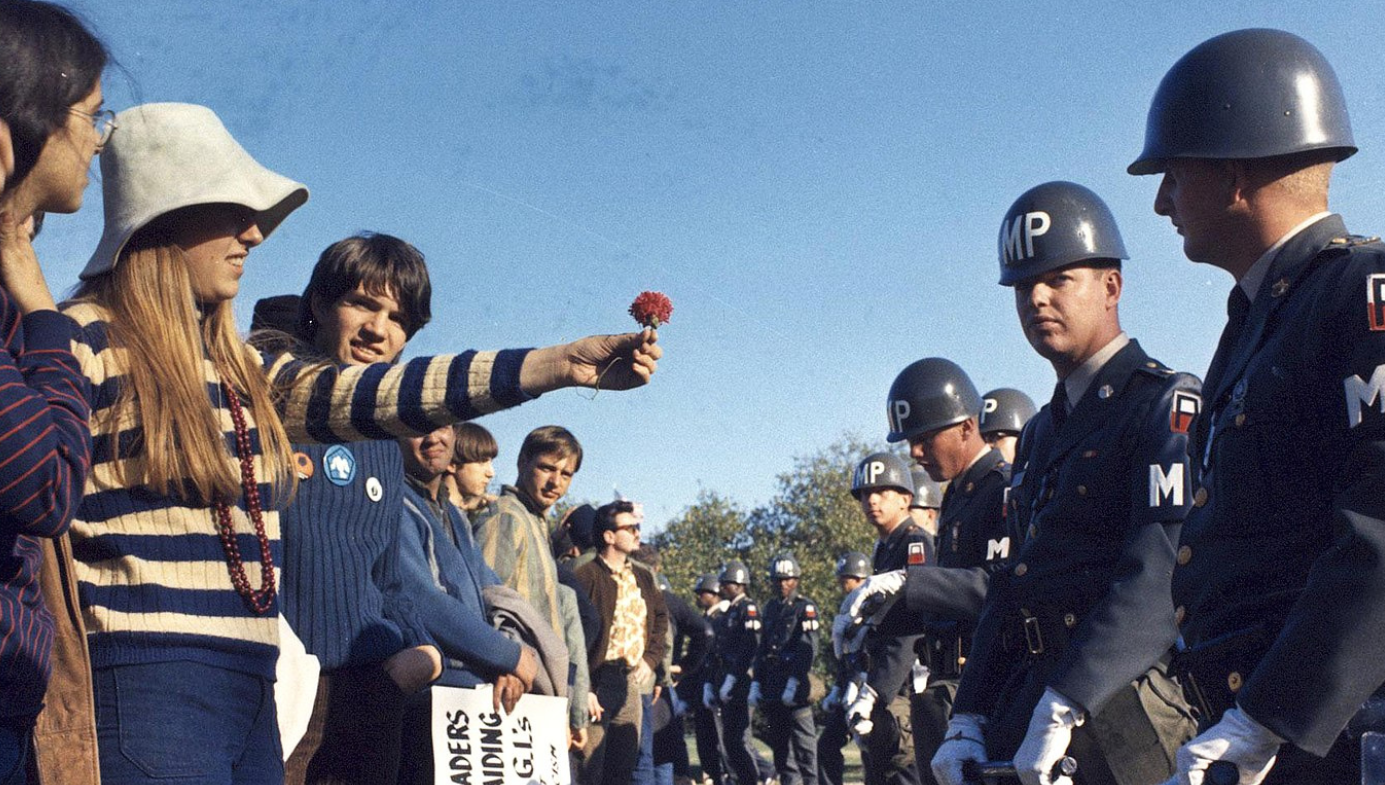

Student protesters on our campuses these last months often invoke the example of the anti-war movement in the late 1960s, and that is indeed a useful example. In fact, there were two different anti-war movements back then, or two groups of activists motivated in different ways. The two overlapped and sometimes worked together. But one group was ideologically driven, while the other, if I can coin a phrase, was people-driven. One was focused on the matter of US imperialism, the other on the images of burning villages in Vietnam; one looked forward to a communist victory, the other, while still opposing the American war, dreaded it.

In 1967, I was co-chair of the Cambridge Neighborhood Committee on Vietnam (CNCV)—a position I won by talking too much at the founding meetings. My co-chair wasn’t a professional leftist or an academic, she was a young woman who worked in film and turned out to be an extremely competent manager of the Committee’s daily work. I was in charge of political argument. The work was community organising against the war, of the kind modelled by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Our activists, most of whom were students, went door to door looking for someone who would host a block meeting at which one of us could explain our political position. At the same time, we were collecting signatures to force a referendum on the war in the city of Cambridge, MA.

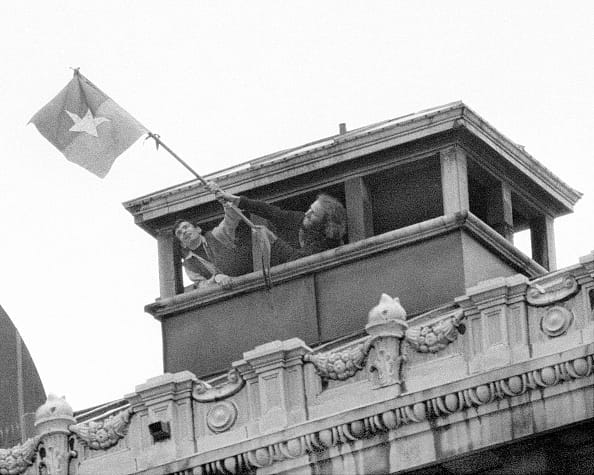

Ours was a modest politics, so people with different views could easily cooperate. We did not organise marches through the city, so I did not have to argue against carrying VietCong flags, as many of our activists would have wanted to do. Around the country, the flags were an early sign of the coming divisions. I did have to argue with people from the sectarian Left who thought that the referendum was altogether too modest a project. They wanted to start the revolution—as, later on, some of our activists, or people like them, wanted to bring the war home.

What were the differences, not yet fully apparent, in CNCV? I had better begin with my own position, which was muddled, to say the least. I was then (and for many years after) closely associated with the magazine Dissent, the founders and editors of which were my political mentors. They were mostly ex-Trotskyists, now democratic socialists and internationalists, and some of them had travelled a lot, meeting comrades abroad. They literally knew the names of all the independent leftists that the Vietnamese communists had murdered. This made it difficult for them to support an anti-war movement whose work, objectively considered, would lead to a communist victory. They would probably have endorsed the American intervention if only a government had emerged in Saigon to defend democracy, end corruption, and win hearts and minds in the countryside.

Alas, there was no such government. The VietCong won the battle for hearts and minds, and the American war became a war against the rural population of Vietnam. I was one of the youngest dissentniks and probably the first to join the call for an American withdrawal. But I didn’t long for a communist victory. I knew, and I had been told by my fellow editors and writers, that cruelty and repression would follow. I just thought that the immediate cruelties of the war, above all, the burning villages, required a political response. In CNCV, there were people like me—activists without an ideology, living in the present. But there were many others who thought that they were engaged in a world-historical struggle against American imperialism: they are the nearest ancestors of today’s pro-Hamas militants.

CNCV eventually obtained enough petition signatures (and pro-bono legal assistance) to force the city council to authorise a city-wide referendum on the war in November ’67. Some 40 percent of the people of Cambridge voted against the war, which was a victory of sorts. But we lost every working-class neighbourhood and swept only Harvard Square and its surroundings, which was not what our activists had hoped for. It was, however, what we should have expected by sending mostly draft-exempt college students to knock on the doors of people whose kids were serving in the army, some in Vietnam. We hadn’t thought much about how to address the men and women we aimed to convince. It was community organising without a basic respect for the community. So we probably contributed to the rightward drift of the working class in the decades that followed.

After the referendum, CNCV broke apart. Some of our activists moved into draft resistance, while others joined the various fragments of the 1960s Left: Maoists, Weathermen, or what remained of SDS. The activists I call people-driven turned to electoral politics in the belief that political campaigns like those of Eugene McCarthy (whom I supported) or Robert Kennedy might actually end the war. In the summer of 1968, we were at the Chicago convention, nominating McCarthy (after Kennedy was murdered), while the ideologically driven leftists were in the streets fighting with the police and helping Nixon to win the November election.

After that, the war dragged on for years, though with declining popular support. A new organisation, Veterans Against the War, helped a lot, I think, to convince Americans that there was something radically wrong with our engagement in Vietnam. Theirs was the most concrete and least ideological opposition movement—they talked about their experience in Vietnam, and they didn’t talk about imperialism.

When the war finally ended, the communists in power behaved exactly as my Dissent colleagues had predicted they would. Thousands of Vietnamese men and women were sent to “re-education” camps where they were beaten, tortured, and killed. Fearing the camps, tens of thousands fled the country by sea. The exodus of “boat people” continued for almost ten years; about 25 percent of their number—as many as 200,000 men, women, and children—drowned trying to reach distant shores. The ideological Left, with a few exceptions, found that it had nothing to say on behalf of these victims of the regime it had helped bring to power. The victims were invisible or unimportant, given that American imperialism had been defeated.

My friends—the people-driven activists who had also helped to make the communist victory possible—were at least critical of the new government in Saigon and ready to help its fleeing citizens. Still, ours was a difficult politics: condemning the war while acknowledging the repression to come if the war was lost, and then condemning the repression. But I think we did better than those leftists who rushed to Hanoi to celebrate the communist victory, without any thought for the people in the South.

What would a better politics—or what I described as a decent Left after 9/11—look like today? It would have to oppose both Hamas and the current government of Israel; it would have to be people-centred, equally concerned with the wellbeing of Palestinians and Israelis. For the Palestinians, this requires, first, a plan for the reconstruction of Gaza and, second, the opening of a path toward self-determination. For Israelis, it requires the re-establishment of physical security after the trauma of 7 October. But these requirements have a crucial precondition: the defeat of religious and ideological zealots on both sides.

Hamas’s Islamist zealots are a threat to ordinary Israelis—to their state and to their lives. And messianic irredentists and ultra-nationalists in Israel are a threat to ordinary Palestinians—to their already constricted living space and to their lives. These groups also threaten their own people, whom they want to discipline and mobilise for a holy war.

A decent left-wing politics shouldn’t be hard to figure out: support anyone, Palestinian or Israeli, who aims to secure freedom and security for both nations. An ideological focus on American imperialism and Israeli “settler-colonialism” isn’t just a diversion from a people-centred politics, it is actually a program for a war against the Israelis—a war that holds no promise of freedom for the Palestinians. The call for total victory “from the river to the sea” in both its Hamas and its messianic Zionist versions is, similarly, a program for war, each zealotry against the other. It is time for leftists to forego ideology and think only of a life of safety and comfort for Israelis and Palestinians alike.