Politics

The Great Divide

As CCP corruption and waste has run rampant, the gulf between rich and poor has widened.

Social classes are fixed. The poor can never achieve anything.

~Li Hai

During the years of China’s rise, politically connected entrepreneurs built up enormous wealth. Onlookers called it a Gilded Age; they compared it to the boom years in the late 19th-century United States. Vivid tales of excess fired the public imagination. The head of one state lender was said to keep a personal harem of more than a hundred mistresses; when he was arrested, the authorities found three tonnes of cash in his home. A police chief built his own private museum collection featuring everything from priceless works of art to fossilised dinosaur eggs.

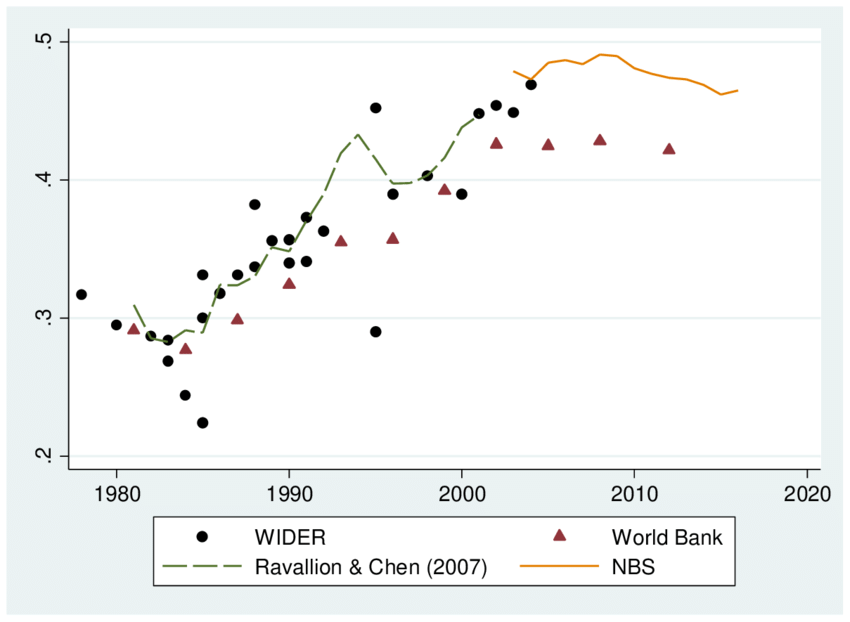

As corruption ran rampant, inequality grew, and by the turn of the millennium, the country’s Gini coefficient had risen to 0.45. (China’s own leaders draw a red line at 0.40, seeing anything higher as potentially destabilising.) Today the Gini coefficient continues to hover around 0.46. But hard statistics do not capture the essence of the economic gulf; for that, we will require snapshots of individual circumstances. We need to picture the Shanghai businessman who boasts that his neighbour’s dog will only drink Evian. And then we need to remember the rural women who venture out to crack the river ice by hand so they can wash the family’s clothes.

China’s president has made a lot of noise about the supposed eradication of absolute poverty under his stewardship, but half the nation still subsists on $140 per month or less. Some 300 million citizens live below the poverty line, while a further 180 million are classed as “very poor.” In this 21st century, toilets are still holes in the dirt for many ordinary people.

After a lifetime listening to stories of the great miracles wrought by the Chinese economy, the truth has a disorientating, even surreal quality—in the end, China never did get rich after all. Those golden years of double-digit growth belong to history. Spiralling debt; lethargic household consumption; ever-rising youth unemployment; a property industry in crisis; a demographic timebomb—today, every trend is an adverse trend. Whether the data portend dramatic collapse or merely decades of slowdown, recovery is not an option.

China’s economic woes are hardest on the very migrant workers who played such a crucial role in the nation’s rise. For decades, these nameless millions bore the economy on their shoulders. From the villages and mountains of the heartland, they poured out to the eastern megacities to find work. They pieced together phones on factory floors, loaded iron into blast furnaces, and laid asphalt under the churning sun. They joined the construction crews conjuring skyscrapers from the earth at breakneck speed, and though they knew they would never live or work in those skyscrapers, they trusted that all the years of hard labour would allow them to relax in their old age. Instead, they now find that they must keep working. Without a city hukou, most of them have no pension and no claim to subsidised healthcare.

Hukou is the Communist Party’s household registration system, under which every citizen is considered to be the permanent resident of their hometown. Those who move to the cities for work do not enjoy the rights of city-dwellers. And they must leave their children behind, because no free urban education is available to the children of outsiders. In practice, this is institutionalised inequality; a caste system. China’s rural migrant workers are essentially illegal immigrants—all 300 million of them. One Zhengzhou businessman provides an especially arresting image: hukou is a “cattle ear-tag the state clipped us with.”