Art and Culture

Jean-Luc Godard in Retrospect Part II: Fanaticism and Failure (1966–2022)

After half a decade of critical adulation, Godard’s career slumped into doctrinaire Maoism, bitterness, incomprehensibility, and irrelevance. It never recovered.

Part One of Charlotte Allen’s two-part Godard retrospective can be read here.

VII. Pictures of Chairman Mao

Jean-Luc Godard’s feverishly assembled early-1960s collection of cinematic homages, sententious literary references, half-baked forays into poorly understood Hollywood genres, and assaultive egotism was actually his golden age. After 1965, he launched into something that managed to be even more conducive to audience boredom: his Maoist period.

In 1966, Godard met and fell under the tutelage of Jean-Pierre Gorin, a Jewish culture critic for Le Monde and aspiring filmmaker with intellectual pretensions. He was like Godard only worse because he was 13 years younger and presumably more in tune with the times. Godard’s philosophical mentor had been Jean-Paul Sartre, whose authenticity-focused existentialist theories were passing into datedness as the 1960s rolled on. Gorin’s theories drew on the deconstructionist trinity of Louis Althusser, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Lacan, who had been his professors at the Sorbonne. The postmodernist presuppositions of these men—that there is no such thing as authenticity, much less truth, just socially conditioned “texts” epiphenomenally serving some power structure—were to become the rage in university humanities departments for decades to come. Gorin loved to pepper his film analysis with the fashionable words “narrative,” “discourse,” and “resistance” lifted straight from the postmodernist playbook. His cinematic aspirations meant that Godard was obviously the best thing that ever happened to him.

Gorin was also a hardline Marxist. Godard had definitely been a man of the Left for most of his adult life—this was the “hate” part of the love-hate relationship with consumer goods that showed up in his movies, as well as the source of the anti-authoritarian ethos of À Bout de Souffle (1960), Vivre Sa Vie (1962), Bande à Part (1965), Alphaville, and Pierrot Le Fou (both 1965). Godard’s first film with Karina, Le Petit Soldat (The Little Soldier, 1960), had been banned for three years by France’s Gaullist censors because (according to reviewers—I haven’t seen it) it portrayed the Algerian War in equivocal terms: rebels and right-nationalists as cousins in terrorism and torture. Godard’s intellectual hero, Sartre, might have championed “authenticity,” but Sartre’s notion of authentic choices always seemed to mean choices of which the Communist Party approved.

As the 1960s progressed, the hitherto mostly apolitical Cahiers du Cinéma crowd, of which Godard had been a leading figure, lurched toward radicalism in near-unison like a school of fish. In 1963, its writers ousted then-editor-in-chief Éric Rohmer—a practicing Catholic focused (like his Catholic predecessor André Bazin) on film aesthetics—and replaced him with Jacques Rivette, who took the journal in an overtly Marxist and Brechtian direction. Three years later, Rivette released La Réligieuse (The Nun), a film that included (as might be expected of a film based on a work by Enlightenment philosophe Diderot) scenes of convent cruelty and implicit lesbianism. De Gaulle’s socially conservative minister of information, Yvon Bourges, responded by banning the film in France, an act of censorship that galvanized French writers and intellectuals in Rivette’s defense. Godard wrote a melodramatic “first they came for the Jews”-style manifesto for Le Monde in which he declared that he was able, for the first time in his life, to “look head-on at the true face of present-day intolerance.” He became an open enemy of Charles De Gaulle and his government, to be sure, but also of the United States, whose militarism in Vietnam, capitalism, and consumerism he believed to have corrupted authentic French culture.

Gorin, meanwhile, introduced Godard to hardline Marxist dialectic and, eventually, to Maoism, whose wholesale cultural destruction and enforced social uniformity—Little Red Books, re-education camps, identical drab clothing, and above all, the terrorization of the old by the Red Guard young—mesmerized the Western Left during the latter half of the 1960s. Stalinism, they believed, was moribund and sclerotic, whereas Maoism was young and forward-looking. This was the era of the “youthquake,” and no 1960s cohort was more entranced by youth and revolutionary violence than intellectuals of Godard’s age. He was scarcely the only artist and intellectual of the 1960s and ’70s whose misguided notion of social rebellion led him to be ensnared by an ideology of ruthless conformity. Sartre was another.

Godard’s movies from 1966 onwards reflected these new preoccupations. Deux ou Trois Choses que Je Sais d’Elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her, 1967) was a nearly plotless cinematic diatribe against all things American, especially the Vietnam War but also American air travel, American-style high-rise apartment buildings in the brand-new, mid-century modern postwar Parisian suburbs (this was before the banlieues turned into Islamic-immigrant redoubts), and American consumer products made beautiful by cinematographer Raoul Coutard’s camera: Ajax, Reynolds Wrap, and Lucky Strike cigarettes.

The meager storyline concerned a high-rise-dwelling housewife named Juliette—played by Marina Vlady, briefly Godard’s post-Anna Karina girlfriend—who becomes a part-time prostitute while her husband is at work so she can buy herself designer clothes. Housewives-turned-ladies-of-the-afternoon was a favorite director’s theme of that era on account of its metaphoric possibilities (Luis Buñuel’s Belle de Jour was released the same year). It was a theme that fed into Godard’s recurring fascination with prostitution motifs for his leading ladies. At one point, Juliette and her manicurist, Marianne, another dabbler in commercial sex, parade naked except for TWA and Pan Am (then the two largest US airlines) carry-on bags over their heads. The message was as subtle as “The revolution is not a dinner party.”

Just as jackhammering in its dogmatic Marxism was another of Godard’s efforts during that frantic year: Week End. The plot here revolved around a bourgeois couple (Jean Yanne and Mireille Darc) intent on murdering each other so they could be with their respective lovers—but not before they have driven to the south of France (as in Pierrot le Fou, but this time in a Facel Vega instead of a Ford Galaxie) to either press Darc’s dying wealthy father into signing all his money over to them or kill him. (The father predeceases their arrival, so they kill Darc’s mother instead.)

The critics loved Week End, which they decided was an allegory of Western society in its autophagic demise. They especially loved Raoul Coutard’s eight-minute tracking shot along a queue of luxury vehicles, stalled on their way to vacationland by a particularly bloody auto accident that has left corpses and raging automotive bonfires strewn on the roadside. (Week End was Coutard’s last collaboration with Godard for decades.) I must say that I quite enjoyed Week End’s finale, in which a troupe of armed cannibal-hippies kill and eat Jean Yanne. After all, I’d had to endure a four-minute soap-box sermon preached to a drumbeat by two disheveled garbagemen meant to represent the exploited French proletariat. Fin du Cinéma, reads one of the film’s end-titles, marking Godard’s ostentatious farewell to the medium. If only.

Later that same year came the movie that ended my interest in Godard’s work for a half-century: La Chinoise. It starred Anne Wiazemsky, who married Godard that year and would technically remain his wife until 1979 (by the time they divorced, he had already been living for years with Anne-Marie Miéville, who would become his third wife). Although a granddaughter of the Nobel Prize-winning French novelist and critic François Mauriac, Wiazemsky was not particularly intellectual, barely passing her baccalaureate exams thanks to last-minute tutoring (according to Godard biographer Richard Brody). Her performances relied on her dark-eyed, otherworldly beauty—vaguely reminiscent of Karina’s—reverently photographed by Godard.

But Wiazemsky had two things going for her. At the age of 18, she had starred as a peasant girl in Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), Robert Bresson’s infinitely sad film about a brutishly mistreated donkey. That was the year Godard met Wiazemsky, which meant she was the same age as Karina had been when she met Godard, except that Godard was now 36, not 30—that is to say, twice Wiazemsky’s age. Wiazemsky was a student at the brand-new Paris-Nanterre University in the city’s outskirts, notable for its enormous student body and block-like Brutalist architecture. Overnight, Nanterre became a locus of the leftist radicalism that was to explode into the massive student-led series of strikes in May 1968 that paralyzed France, ended De Gaulle’s political career, and inspired a domino cascade of violent student protests around the world. Daniel Cohn-Bendit, 22-year-old chief agitator of the soixante-huitards, was an off-and-on student there. Unlike the generally apolitical Karina, Wiazemsky was overtly leftist in her sympathies, and she provided Godard with an entrée into the youth culture he craved as he approached middle age.

Gorin and Godard’s association—and a few years later, collaboration—certainly paid off for the former. In 1975, Gorin leveraged it into a visual-arts professorship at the seaside campus of the University of California San Diego, where he made a handful of documentaries and taught until his retirement in 2023. For Godard, the association meant a lapse from interminable film whimsy into interminable film didacticism. La Chinoise, with its monotone Maoist study sessions inside Godard’s high-ceilinged fin-de-siècle Paris apartment, was only the beginning.

In 1968, Godard moved briefly to London to make an English-language movie that he titled One Plus One. About half of it is actually riveting—long sequences showing the Rolling Stones in a recording studio practising and developing what would become perhaps their greatest song, “Sympathy for the Devil.” As a music documentary, the film is first-rate. Tony Richmond was the cinematographer, and his camera rolls regally through the Stones’ enormous studio as the Stones rehearse. Mick Jagger’s then-girlfriend Marianne Faithfull and Keith Richards’s then-girlfriend Anita Pallenberg make glamorous appearances as backup-singers. I’ve watched the movie at least three times over the years and I’ve never gotten tired of those scenes.

Bill Wyman, Mick Jagger, and Jean-Luc Godard while filming Sympathy for the Devil, 1968. pic.twitter.com/xYR5hnNNtJ

— Cinephilia & Beyond (@CCinephilia) March 19, 2015

The problem is One Plus One’s other half, which was Godard at his most “instructional” (as New York Times reviewer Roger Greenspun delicately put it). Much of this material consists of purported Black Panthers (or some other variety of black-nationalist clone) occupying an automobile junkyard plastered with anti-US graffiti (eg: “CIA + FBI = TWA + PAN AM”—Godard seemed to harbor a special animus against those two now-defunct airlines). The Panthers toss rifles to one another and lecture across the fourth wall via such Gorin-esque slogans as: “The only way to be an intellectual revolutionary is to give up on being an intellectual.” In other scenes, Anne Wiazemsky—as an allegorical figure named “Eve Democracy” attired in floaty hippie dresses—wanders through a forest. Her dead body is later splashed with red paint and hoisted on a crane above a beach invaded by the revolutionaries.

Godard subsequently got into a snit with his producer, Iain Quarrier, over the film’s ending. Quarrier insisted that the film conclude with the Stones’ completed version of “Sympathy for the Devil”—the end-product of the rehearsals and what the audience would be waiting for. Quarrier also changed the film’s title from Godard’s incomprehensible One Plus One to the immediately recognizable Sympathy for the Devil. Godard was incensed that his deliberately open-ended work of art now had closure. He stormed onto the stage before its premiere at the London Film Festival and told the audience to demand refunds. Anyone who refused to send the money to Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver’s defense fund instead was a “bourgeois fascist,” he announced. Then he punched Quarrier in the face. He later projected his own cut of One Plus One onto one of the theater’s exterior walls.

VIII. Un Homme Dégueulasse

In 1969, Gorin and Godard founded the Dziga-Vertov Group, named after the Soviet documentarian (1896–1954) who contended that moviemaking could be a revolutionary act. Godard continued making movies—four of which were for Dziga-Vertov plus a handful of collaborations with other politically minded directors—but he insisted on crediting them to the “collective.” He disowned his previous claim to be an auteur and even dismissed One Plus One/Sympathy for the Devil as his “last bourgeois film.”

In 1970, Godard and Gorin gave a joint interview to the Evergreen Review that reads like the product of a Maoist struggle session. “I was a bourgeois filmmaker and then a progressive filmmaker and then no longer a filmmaker, but just a worker in the movies,” Godard informed the magazine. “The notion of an author, of independent imagination, is just a fake.” He also completely changed his sartorial image: the natty suits and ties of his glamorous years with Karina were replaced by the rumpled jeans, flyaway hair, and stubble that would be his signature look for the rest of his life. The younger Gorin, by contrast, had a leonine head of hair and projected youthful leftist glamour.

Even the critics who had hitherto lionized Godard agreed that the movies he made during his Dziga-Vertov phase were pretty terrible (I haven’t seen any of them). Le Vent d’Est (Wind From the East, 1970) was a critique of American capitalism and the American cowboy West starring Anne Wiazemsky, which famously contained directions for making a Molotov cocktail (the New York Review of Books had also carried a Molotov cocktail recipe in 1967). In New York magazine, John Simon pronounced Le Vent d’Est “a piece of infantile Maoist propaganda, so boring, antifilmic, sloppily made, and yes, insane.” Pravda (also 1970) was blistered by Greenspun in the New York Times for accusing the doomed Czechoslovakian student protesters in 1968 of “suicidal humanism.”

During the spring of 1970, Godard—armed with the Little Red Book that was now his daily reading—traveled to Jordan to make a Dziga-Vertov movie about the Palestine Liberation Organization and its struggle against Israel. The movie was to be titled Jusqu’à la Victoire (Until Victory) and Godard shot ten hours of rushes during his three-month stay in Jordan, recording what he considered to be the real lives of the revolutionaries: women in refugee camps learning how to read, Palestinian poets reciting their verses, earnest conversations with PLO leaders. The footage was designed to demonstrate the Dziga-Vertov dogma that political revolution and aesthetic revolution went hand in hand. But after Godard returned to France, it turned out that the PLO leaders in Jordan were more interested in liquidating the country’s Hashemite rulers than fighting the Israelis. A Jordanian crackdown followed, during which many of the PLO members Godard and Gorin had interviewed were killed. Jusqu’à la Victoire was shelved, and by 1971, the Dziga-Vertov Group was no more.

The other thing that was no more was Godard’s marriage to Wiazemsky. She couldn’t stand Gorin, whom she regarded (according to an interview she gave to Richard Brody) as “the political commissar” in her husband’s life. The couple separated in 1970, but by then, Godard had already taken up with Anne-Marie Miéville, who moved into his Paris apartment after Wiazemsky left. She was 35, closer to Godard’s age than Wiazemsky, and she had a young daughter, which meant she would not pester the determinedly childless Godard into becoming a father. She was also Swiss, like Godard, and like Godard, she had thrown herself into radical left-wing politics. A photographer and sometime singer with filmmaking aspirations, she had a day job managing a pro-Palestininan bookstore, where she used her contacts to get him introduced to some of the Palestinian figures in Jusqu’à la Victoire.

Godard’s partner Anne-Marie Miéville has been 40 years a filmmaker. Time for a closer look? https://t.co/6luJrHRkEK pic.twitter.com/SCKYDP4UTt

— Sight and Sound magazine (@SightSoundmag) February 26, 2016

Miéville somehow managed to put up with Godard’s political self-indulgence, emotional volatility, increasingly slovenly appearance, and financial improvidence for decades. By this point, he was surviving on loans from friends, and it may be that his new lover functioned mostly as a nursemaid/mother-figure for him, in contrast to the extremely young women who excited his passion but did little to give him stability. That might be wrong, of course. According to Richard Brody, Godard wrote Miéville every day when she traveled to Switzerland to visit her family, and he marked his calendar on the days they made love.

Godard and Gorin made two more movies together after the demise of Dziga-Vertov. Both films revolved around Jane Fonda, who was living in France after her divorce from Roger Vadim and going through her own radical phase. The Godard-Gorin 95-minute feature, Tout Va Bien (All’s Well, 1972) starred Fonda and Yves Montand, who had also conspicuously allied himself with the French Left. Godard was broke by this point, so out of political solidarity, Fonda and Montand agreed he could pay their salaries from the movie’s earnings. Tout Va Bien was a kind of throwback to some of Godard’s pre-Dziga-Vertov efforts, except with overtones of class warfare. Montand played a fictional New Wave film director reduced to making television commercials, while Fonda played his American girlfriend, a newscaster for an American television network.

The film’s ambience was pure 1970s, and it explored, among other things, brand-new Second Wave feminism. Fonda bustled around the newsroom in enormous bell-bottom pants (a novelty for Godard, whose female stars had heretofore mostly worn dresses) and the stylish shag hairdo she wore in Klute, uttering women’s-lib complaints about male dominance. The plot involved a strike by exploited workers at a sausage factory, who then kidnap Fonda and Montand. Godard clearly had no idea how sausages were actually made. The workers wear aprons spattered with blood from chest to hem, but all we see of the manufacturing process is a line-up of ready-to-fry wursts that look as though the prop mistress bought them at Carrefour and arranged them on the set’s assembly line.

Godard ended up alienating Fonda and Gorin, just as he ended up alienating almost everyone else. In 1972, Fonda made her “Hanoi Jane” trip to North Vietnam, where she was photographed sitting atop an anti-aircraft gun used to shoot down American planes. The photo was reviled by US conservatives but Godard’s and Gorin’s 1972 film Letter to Jane attacked her from the opposite perspective. For 45 long minutes, the two men conducted a dialogue over a series of still photos that included a repeated image of Fonda chatting sympathetically with North Vietnamese civilians. She had failed to commit herself to the North Vietnamese revolutionary project, they argued, or even pay attention to what her North Vietnamese listeners said as she shed crocodile tears. Fonda was fairly sanguine about those ideological criticisms, all things considered. In a 2023 interview with Vulture, she said: “I thought it was a big pile of bullshit. … [Godard] was a great filmmaker. I take my hat off. But as a man? I’m sorry, no.”

Gorin had actually done nearly all of the directing of Tout Va Bien. In June 1971, just before filming started, a motorcycle on which Godard was riding pillion collided with a bus. The impact fractured his skull, broke his pelvis, nearly severed an artery, and caused him to lose a testicle. He was in a coma for nearly a month and his recovery took many more. Although he was barely able to provide the movie’s narrative skeleton, everyone maintained that he was still actively involved so that the movie’s insurance company would continue to cover his hospital bills.

When Gorin left France to live in California in 1973, Godard promptly moved the partnership’s equipment to his own studio and left Gorin on the hook for the unpaid rent on their joint editing room. Gorin got charged with “fraudulent bankruptcy.” Nearly penniless, he phoned Godard from California to inquire about his 50 percent share of an arrangement for Tout Va Bien to be broadcast on French television. According to Richard Brody, Godard replied: “Ah, it’s always the same thing, the Jews come calling when they hear the cash register.” That was the end. It was far from Godard’s only antisemitic slur during that period and after, and remarks like these became a locus of controversy when Hollywood awarded Godard an honorary Oscar at a special ceremony in 2010. Godard refused to attend.

Godard also fell out with his erstwhile lifelong friend, Truffaut. During the late 1960s, while Godard was stewing in Maoism with Gorin, Truffaut and his fellow New Wavers Jacques Rivette, Éric Rohmer, and Claude Chabrol were finding their own commercial and critical success as filmmakers. In May 1968, Godard and Truffaut had engineered the cancellation of the Cannes Film Festival in solidarity with the student protests. Nevertheless, tension between the two grew from Truffaut’s unwillingness to go along with Godard’s increasingly doctrinaire Maoism and constant requests for money.

In 1973, Truffaut released La Nuit Américaine (Day for Night), a romantic comedy about the making of a movie and its effect on its cast, crew, and director. It won Truffaut an Academy Award for Best Foreign Film and was widely acclaimed by the critics, who regarded it, along with Les Quatre Cents Coups (1959), as his cinematic masterpiece. Naturally, Godard hated it. He walked out of the opening screening in Paris, and the next day, he sent Truffaut a four-page letter in which he wrote, “Probably no one else will call you a liar, but I will.” Truffaut couldn’t resist going to bed with every beautiful woman he met, and he met quite a few of them, including Catherine Deneuve and her sister Françoise Dorléac. While he was making La Nuit Américaine, Truffaut was carrying on with its female lead, Jacqueline Bisset. Wrote Godard: “[T]he shot of you and of Jacqueline Bisset the other night chez Francis [a still-extant pricey Paris brasserie] is not in your film, and one wonders why the director is the only one who doesn’t screw in La Nuit Américaine.”

"Yesterday I saw 'La nuit américaine' (1973). Probably no one else will call you a liar, so I will."

— DepressedBergman (@DannyDrinksWine) September 19, 2023

--- Jean-Luc Godard's letter to François Truffaut pic.twitter.com/fLdgOMpWsB

Godard went on to describe a more honest movie-about-making-a-movie that he planned to make. Unlike Truffaut’s film, it would focus on the exploited proletarians at the bottom end of the filmmaking wage scale, and he closed his abusive tirade by asking Truffaut to invest half the production costs. It was unfair, he maintained, for Truffaut and other directors to get all the film-investment money for their big productions while Godard scrabbled around for funds. He included a note to Jean-Pierre Léaud, the young star of Les Quatre Cents Coups and La Chinoise, asking Léaud to lend him money as well.

Truffaut was enraged. He wrote a scathing 30-page reply, which began by refusing to give Godard a dime and blasting him for trying to beg from Léaud, who was still in his 20s and had relatively little money. He called Godard a hypocrite for pretending to be a champion of the proletariat while he fawned over stars like Jane Fonda and mistreated his own film crews. He accused Godard of wallowing in self-pity and doing nothing—financial or otherwise—to help the penniless widow of André Bazin, the man who gave Godard his first writing assignment at Cahiers.

Truffaut called Godard a “shit” several times in that letter, but more significantly, he used the French word dégueulasse (“disgusting”) to describe Godard’s behavior. He used that word three times. It was the same word that Godard had famously played upon at the end of À Bout de Souffle. A subtle reminder, perhaps, that it was Truffaut who had written the never-used screenplay for that film and was thus the true creator of Godard’s only lasting work. The two never reconciled, and Truffaut died of brain cancer in 1984.

IX. Sex and Seclusion in Switzerland

In 1974, Godard and Miéville moved away from Paris and took up permanent residence in Switzerland—first in Grenoble and then, four years later, in Rolle. It was the beginning of that third and final bad cinematic phase for Godard, after the New Wave and the Maoism: the reclusive and the progressively peculiar. This phase lasted until Godard’s death 49 years later, and it accompanied his growing insistence on working in isolation and his personal dishevelment.

Increasingly wary of any collaborators except Miéville, Godard turned from film to mostly working with videotape. Video was a fad among 1970s artistes in general, but it was a vastly cheaper medium that allowed Godard to be his own cinematographer, sound recorder, editor, and distributor. (Richard Brody reports that Godard spent years amassing a roomful of massive analog video equipment that was already nearly obsolete by the time Brody interviewed him for the New Yorker in the summer of 2000.) He could also completely control his location. One of the most fascinating aspects of Godard’s long late phase is the way in which the murmuring waves of Lake Geneva became his new Champs-Elysées, a seemingly omnipresent background.

Godard and Miéville repackaged the Jusqu’à la Victoire footage as Ici et Ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere, 1976), which was supposed to be a cinematic rethinking of his Maoist axiom that cinema was a form of revolution. Actually, it was just more of Godard’s boilerplate Palestinian propaganda: slogans, poems, schoolchildren learning martial arts. The movie’s alternating images of Golda Meir and Hitler, along with Miéville’s vocal support of the Black September slaughter of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics, inflamed Jewish viewers. When Ici et Ailleurs made its commercial debut in Paris in 1976, pro-Israeli militants planted a homemade bomb in one of the two theaters where it was showing and released mice into the other.

"We shall construct peace with the help of this gun."

— graham (@middlemanchette) September 13, 2022

Ici et Ailleurs (dirs. Jean-Luc Godard & Anne-Marie Miéville, 1976) pic.twitter.com/fOPqWewyxv

Then, while Ici et Ailleurs was winding up in 1975, and at the urging of his longtime producer, Georges de Beauregard, Godard launched into a remake of À Bout de Souffle (Beauregard had produced the original and most of Godard’s New Wave repertoire). The new take, Numéro Deux (Number Two), was shot almost entirely on videotape in Grenoble because Godard was residing there at the time. It apparently bore no resemblance whatsoever to the 1960 original. I’ve never seen the film, and I never will, so here is Wikipedia’s plot summary:

The wife complains of her constipation … to her children. When the husband discovers that she has slept with another man, he takes his revenge on her by sodomizing her, which only makes her constipation worse. During this sex, they realize that their daughter has been watching them. They discuss this complacently. They discuss how a woman’s body is described as electricity, charging up and discharging, and sex is work when it becomes something for a child to watch. … In one sequence, mother and daughter cavort around in the living room at lunch time—the mother wearing nothing but an untied robe and the daughter in underwear—while the son toys with his meal in the kitchen and holds his head in boredom.

“Numéro Deux stands out as one of Godard’s least accessible films,” admitted Slant critic Calum Marsh in a textbook example of understatement. The film received almost no critical attention and wasn’t released in the United States until 1981—after which it vanished until 2012, when the now-defunct Olive Films produced a DVD that is almost impossible to find these days. Still, it has its enthusiasts, including Marsh, who continued: “But it’s also one of his most essential and, in many ways, perhaps his most exciting.”

Numéro Deux had a disturbing aspect: the presence of children in scenes of explicit and unpleasant sexual activity, along with adult nudity (the grandfather in Numéro Deux sits naked in the kitchen reminiscing about his past Communist Party activism). This was a leitmotif of Godard’s mid-1970s productions. Richard Brody suggests it had to do with the presence of Miéville’s daughter, who was passing from childhood to adolescence in the intimacy of the Godard-Miéville household. It also had to do, I think, with a peculiar mid-1970s combination of naiveté and insouciance, especially in highbrow artistic circles, about adult-child sexual frisson that seems incomprehensible a half-century later.

In 1977, Roman Polanski, then aged 43, photographed a 13-year-old girl topless before allegedly plying her with champagne and quaaludes and sodomizing her. Polanski fled the United States permanently in 1978 and later maintained in an interview with Martin Amis that “[e]veryone wants to fuck young girls.” That statement was undoubtedly true (cf. Prince Andrew), but it also displayed an indifference to the vulnerability of young people that was typical of the time. I remember reading a feature story in the Los Angeles Times around the same time about a wealthy local pedophile who had taken a fatherless young boy under his wing and onto his yacht to become his lover. The Times reporter blithely opined that such relationships might seem shocking to the prudish, but they represented the only real love that abandoned children might experience.

The situation among French intellectuals was even more egregious. In January 1977, Le Monde published a petition urging the lowering of the age of sexual consent to 13; the 69 signers were a Who’s Who of the French cerebral aristocracy: Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Gilles Deleuze, Roland Barthes, and René Schérer, Éric Rohmer’s philosopher-brother. Most of them, as Richard Brody points out, likely had no intention of having sex with pubescents themselves, but they enjoyed the thrill of rebelling against conventional bourgeois morality.

In 1976, Godard and Miéville made a series of six documentaries for French television about everyday life (Six Fois Deux) that included a lengthy black-and-white clip of Miéville’s daughter, Anne, then aged about ten, doing a ballet dance wearing nothing but toe shoes. The video was innocent enough, and most parents find their own naked children adorable. But its inclusion for the delectation of a TV-viewing public was… odd. The only mitigating factor was that it wasn’t much of a public. Although the French press covered the making of the series with fascination, few viewers turned on their sets to watch it.

Even odder and more unsettling was Godard’s next television project with Miéville: an adaptation of the 1877 French children’s classic, Le Tour de la France avec Deux Enfants (Tour of France with Two Children) written by Augustine Fouillée under the pen name G. Bruno. The story follows two fictional orphan brothers, aged 14 and seven, as they travel around France in search of family members after the Franco-Prussian War and the death of their father. It was essentially a patriotic lesson in French geography, history, culture, foods, and dialects. Godard was supposed to turn it into 12 half-hour segments to be broadcast at Christmastime in 1977, the centennial year of the book’s publication.

The series wasn’t finished until the spring of 1978 and wasn’t broadcast until 1980. (It premiered as a six-hour movie at the Rotterdam Film Festival in January 1979 and had brief runs in Paris thereafter.) As usual, Godard made mincemeat of the source material. He changed the two children to a boy and girl, both aged nine (and played by amateurs). Instead of journeying around late-19th-century France as orphans, he had them living in late-20th-century Paris with their parents. All the shooting, however, took place inside Godard’s studio in Grenoble. There was no script. The children were supposed to reenact their daily lives while Godard peppered them with offscreen questions as he filmed them.

This was undoubtedly a shock to the children, who had expected to be cast as characters in a conventional film with a conventional screenplay. They now found themselves the subjects of a documentary about themselves—or rather, a pseudo-documentary carefully manipulated by Godard. It had little to do with the actual personalities of the children but everything to do with Godard’s idea of children as an oppressed class presided over and punished by adults. He insisted on filming the little girl, Camille Virolleaud, taking off all her clothes and putting on her pajamas as she got ready for bed. Her mother was present during the shooting, the scene was not in itself lascivious, and Godard did nothing untoward. Yet it was, again… strange, and also rather cruel. Richard Brody interviewed the adult Virolleaud in 2001 and 2002, and she told him that she had been “horrified at having to undress on camera” and only did so because “he said that, if I didn’t do what he asked, he was going to stop the shoot.”

Godard was obsessive about control. He was also increasingly isolated in Switzerland as the years passed, with the ever-compliant Miéville as his only companion. There is an aspect of control that is always about dominance over another person, and an aspect of dominance that is always, however slightly, sadistically sexual. Godard’s 1980 film, Sauve Qui Peut (Every Man for Himself) featured a divorced filmmaker named Paul Godard (Jacques Dutronc) who fantasizes about having anal intercourse with his daughter Cécile (Cécile Tanner, the 12-year-old daughter of Swiss director Alain Tanner). When Cécile, who had no idea she would be depicted as an object of pedophilic lust, saw the scene in which “Paul Godard” discussed his fantasies about her at a private screening for the film crew, she crawled under her seat in shame. The movie also featured Isabelle Huppert as a prostitute repeatedly abused by her customers, one of whom asked her to pretend that she was his daughter.

X. Divine Inspiration

Godard’s 1985 film Je Vous Salue, Marie (Hail Mary) was actually one of Godard’s better films—perhaps his best since Le Mépris. That was because, like Le Mépris, it had a coherent story to which Godard hewed fairly faithfully without digressing onto too many ideological and idiosyncratic tangents. Here, the source was the New Testament—specifically the Gospel narratives of Mary and Joseph and Mary’s miraculous conception of Jesus as a virgin.

Godard shot the film in Nyon, a Swiss resort town about ten miles from Rolle on Lake Geneva, and wittily transposed the Gospel mise en scène to the 20th-century working class. Joseph (Thierry Rode) is a taxi driver instead of a carpenter and Mary (Myriem Roussel) is the daughter of a gas-station owner who plays on a basketball team in her spare time. The angel Gabriel (Philippe Lacoste) is a clotheshorse who arrives on earth by jet plane and takes a ride in Joseph’s taxi. The narrative—about a young man who learns that his beloved is pregnant with someone else’s child while indisputably retaining her virginity (as a gynecological exam confirms)—is actually touching, and the film explores it with psychological sensitivity and an interest in the reality of religious faith. Joseph marries Mary and steps into the role of the baby’s legal father, but not without some resentment that he struggles to overcome. The boy Jesus eventually leaves home to pursue—in a direct quotation from Luke’s Gospel—“my father’s business.”

Hail Mary (1985) dir. Jean-Luc Godardpic.twitter.com/7kiSYaGQQP

— cinesthetic. (@TheCinesthetic) June 24, 2023

All of this rests on an orthodox Catholic interpretation of Jesus’s supernatural origins and Mary’s perpetual virginity that seems quixotic for the irreligious Godard. It might have been an intriguing 20th-century variation on the Gospel story and inoffensive to all but the most prudish believers. Joseph wants to glimpse Mary’s naked body before he forever forswears sexual relations with her, and that’s an understandable male impulse—especially since, in Godard’s version, the angel Gabriel is on hand as chaperone to make sure that Joseph stays within respectful bounds. What goes off in the movie is the camera’s relentless focus during that scene on Myriem Roussel’s pubic hair. Full-frontal nudity for female stars was a short-lived filmic fad of the 1960s and ’70s as Hays-style codes crumbled and Woodstock ethics ruled, but it was already unacceptable to feminists by the 1980s and nowadays is mostly restricted to pornography.

Furthermore, Richard Brody’s book reports that, despite his ongoing relationship with Miéville, Godard was obsessed with Roussel. Born in 1961, she was in her early 20s when she filmed Je Vous Salue, Marie—around the same age that Anna Karina and Anne Wiazemsky had been when Godard courted them. She was also extraordinarily beautiful and bore a certain physical resemblance to his previous wives. She’d had small parts in two previous Godard movies, Passion (1982) and Prénom Carmen (First Name: Carmen, 1983). Godard followed Roussel around, writing and phoning her on an almost daily basis and taking her to the New York Film Festival for Passion’s US premiere in 1983.

In Je Vous Salue, Marie, Godard cast himself in the role of God the Father, with all that this particular casting choice might imply. He insisted on filming the scenes involving Mary’s nudity himself, without any crew present, including a scene of Mary writhing in orgasmic pleasure in the presence of the divine. These scenes were not prurient, but they were longer and more explicit than strictly required, displaying an obsessive quality that made it hard to defend the movie (although some critics, including Roger Ebert, a Catholic, tried). Pope John Paul II issued a condemnation (“profoundly wounds the religious sentiment of believers”), and there were demonstrations and occasional bomb threats from angry conservative Catholics at the theaters that exhibited it.

As ever with Godard once he had gone out of New Wave style, Je Vous Salue, Marie generated thin crowds of viewers and tepid reviews from bored critics. “[F]or the first time in my career as a Godard-watcher, I was tempted to let my mind wander,” the New York Times’s Vincent Canby confessed. As a succès de scandale, however, thanks to the Catholic Church, it did enjoy fairly wide exposure that briefly revived Godard’s commercial prospects.

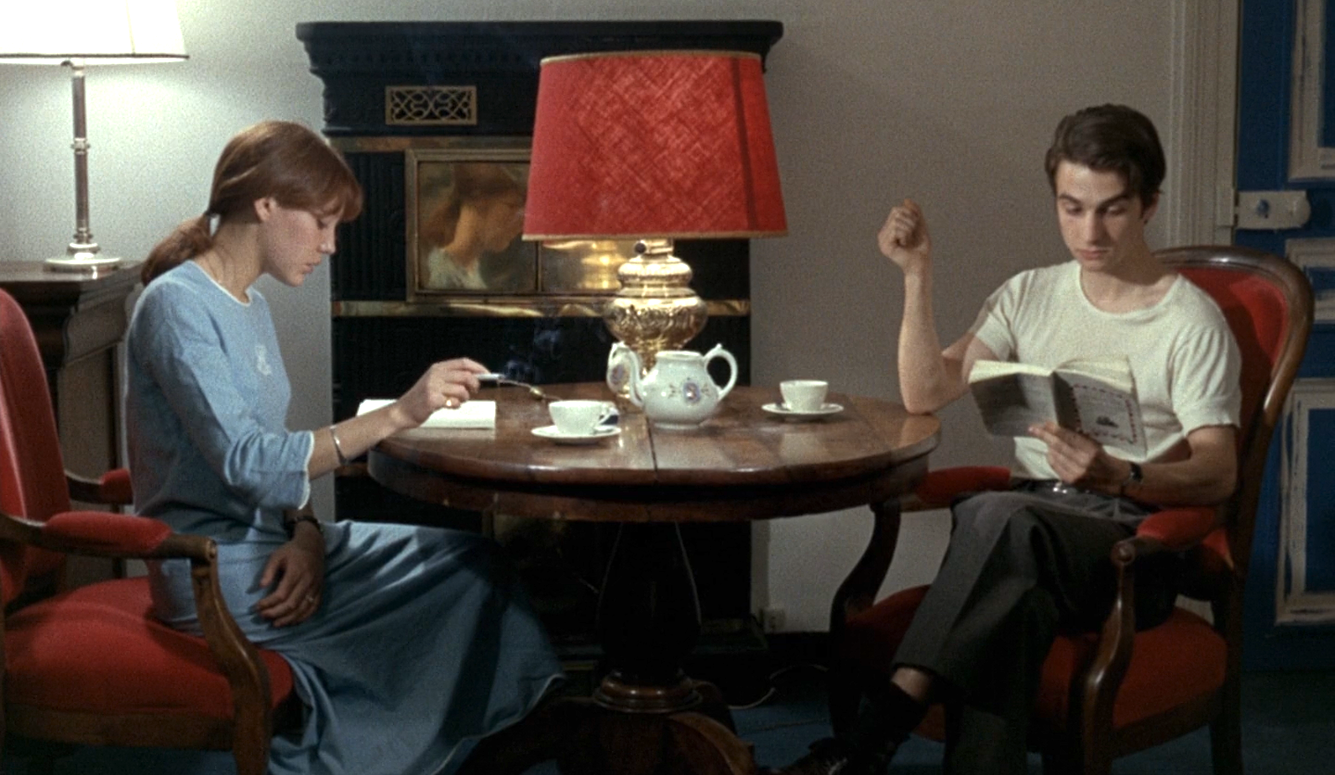

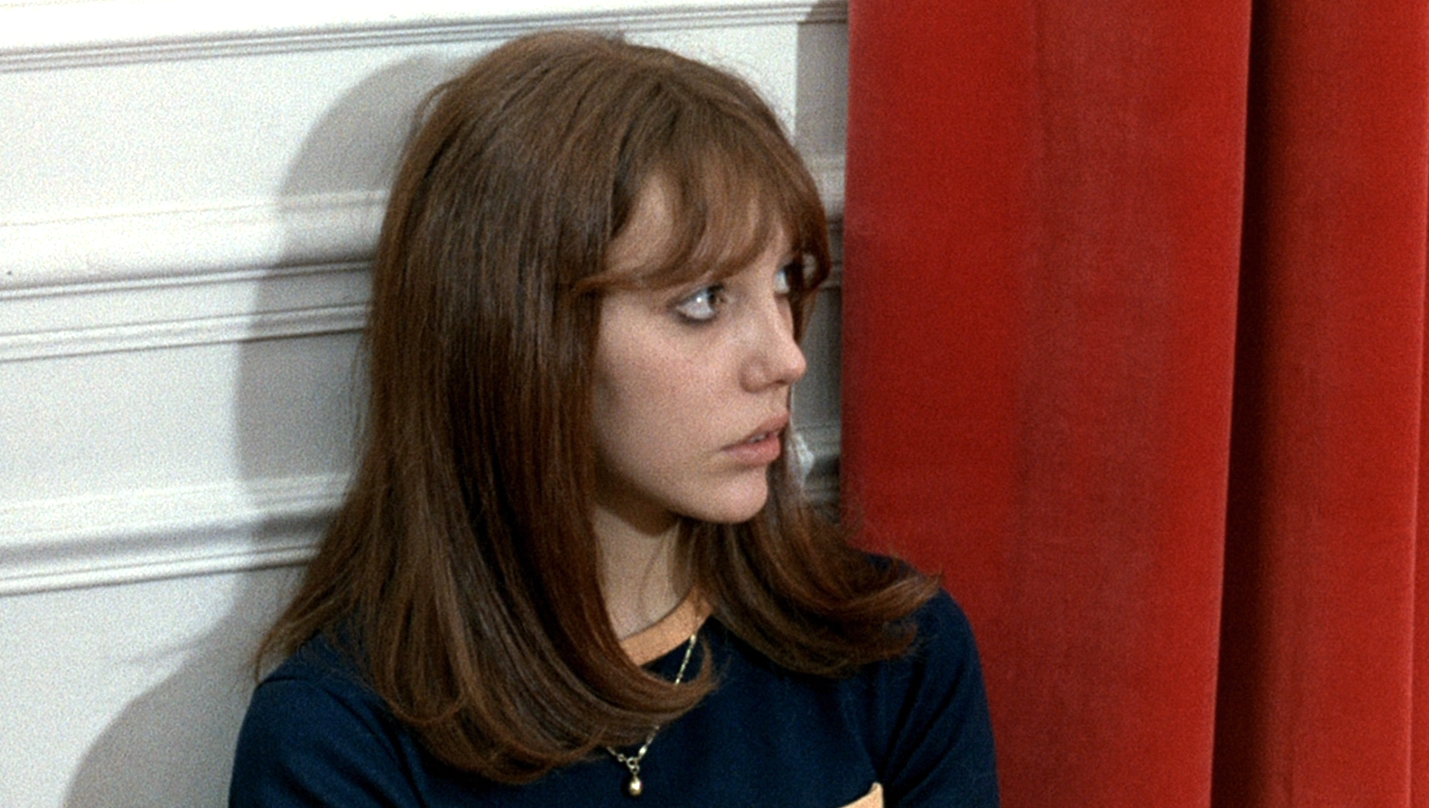

Je Vous Salue, Marie had a companion film released as part of its package. Le Livre de Marie (The Book of Mary) was a 28-minute short entirely written, directed, and edited by Miéville. The plot concerned an 11-year-old girl, Marie (Rebecca Hampton), who has to endure her parents’ separation and their respective new lovers as she is shuttled back and forth between them. It is an extraordinary and moving film, particularly its use of classical music to encapsulate Marie’s psychic dislocation and misery, and it suggests that Miéville had a surer understanding of the medium than her ostentatiously cinemaphiliac life-companion.

Miéville might not have had a film career at all without Godard’s name and sponsorship and perhaps his push as well (we don’t know, since she has given few interviews), but the fact that she so thoroughly sublimated her ambitions to his, producing very little of her own independent work, remains troubling.

XI. An Amateurish Farrago

Which brings us to King Lear. It is hard to know where to begin when trying to assess the sheer colossal, unwatchable awfulness of this movie. After its three-week, nearly audience-free run in New York in January 1988, this disaster finally derailed Godard’s commercial career for good. Suffice it to say that Richard Brody, Godard’s Boswell, dubbed it one of Godard’s “artistic summits.” Indeed, Brody sat through the movie three times during that brief New York run alone, named it “the greatest film of all time” for Sight and Sound magazine in 2012, and has spent the last two decades defending it off and on in the New Yorker and trashing Vincent Canby (among others), who called it “as sad and embarrassing as the spectacle of a great, dignified man wearing a fishbowl over his head to get a laugh.”

Godard managed to persuade Norman Mailer—who had produced and directed several unwatchable films of his own during the 1960s—to be the screenwriter and star. The action was transposed to 20th-century America and Lear became a mafioso named “Don Learo.” Mailer’s actress-daughter Kate Mailer would play Cordelia, and Woody Allen was cast as the Fool (Allen does appear in the final cut, but not in that role). Mailer duly ground out a screenplay that Godard, true to form, never used (Mailer told Brody that Godard never even read it). Filming was supposed to take place in New England, but Godard fell into spells of depression every time he flew over to scout for locations, and then promptly flew back to Switzerland. There were about 70 trips like these, always on Concorde. Most of the budget was consumed in pre-production, generating overruns, and the movie was eventually shot in Nyon.

In September 1986, Mailer and his daughter Kate flew to Switzerland to begin shooting. There, Mailer discovered that Godard wanted to imply an incestuous relationship between Lear and Cordelia as part of his Freudian interpretation of Shakespeare’s play. Mailer hit the ceiling. His own sex life was hedonistic, but he was an old-fashioned father when it came to his children, especially after Godard informed him that they would be called by their real names in his film. He and Kate got onto a plane and flew back to the US the next day. After some false starts recruiting another Lear—Tony Curtis, Lee Marvin, and Rod Steiger (who wanted the film to be shot in Malibu, where he lived) were all approached—Godard finally succeeded in hiring Burgess Meredith. He then persuaded Molly Ringwald, fresh off The Breakfast Club (1985) and Pretty in Pink (1986) to play Cordelia.

A friend told me of a screening of “King Lear” at which Mailer, during the Q&A, called Godard “the second worst human being” he’d ever dealt with. Asked about who was the first, he underwhelmingly cited a New Jersey used car dealer.

— Glenn Kenny (@Glenn__Kenny) January 3, 2022

Godard was already over budget and out of time (his contract had originally called for the film to be finished in early 1986, in time for the Cannes Film Festival that May). So, nearly the entire action of the movie took place in and around the Beau Rivage, hastily filmed in March 1987 so that Godard could make that year’s Cannes festival. The plot was a kitchen sink of incoherence. Godard had some footage that he had shot of Mailer and Kate chatting in their room about the film’s Mafia motif, so he threw it in as a prelude—twice, as a piece of quasi-revenge porn, since he was still seething over Mailer’s abrupt departure. Mailer had a genuine stage presence and a writer’s eloquence, so that conversation with his daughter turned out to be the most interesting part of the movie.

Most of the narrative (if it can be called that) revolves around a fictional descendant of Shakespeare, “William Shakespeare Jr. the Fifth,” played by Peter Sellars. Sellars rambles around the Beau Rivage on a mission to recreate his famous ancestor’s works, destroyed along with the rest of culture in the Chernobyl nuclear disaster of April 1986 (don’t ask how that was supposed to have happened, since it certainly didn’t happen in real life). Sellars also saved Godard’s neck by patching together dialogue for the film that he wrote down on index cards and distributed to the cast, which helped Godard finish shooting in the 12 days he had left after wasting the vast bulk of his allotted time and money. There was almost no crew and certainly no costume budget, so Godard rummaged through the clothes Ringwald had packed in her suitcase and told her which garments to wear.

Fortunately, the Lear-Cordelia incest motif that had sent the Mailers fleeing shows up only in a bloodstained bedsheet (on Meredith’s hotel-room bed, which doubled in the film as Don Learo’s bed) that spared any direct involvement from either Meredith or Ringwald, who was barely 17 at the time. In fact, in a New Yorker essay published shortly after Godard’s death in 2022, Ringwald recalled that she had no idea until she read Richard Brody’s book years later that incest had been one of Godard’s thematic demands or why Mailer and Kate had departed so abruptly.

Ringwald was the movie’s good sport, gamely doing whatever Godard instructed, no matter how ridiculous: wandering among the trees in a white nightgown while leading a white horse, playing dead in the same nightgown while lying with her arms outstretched next to Lake Geneva. The scenes were reminiscent of Anne Wiazemsky’s in One Plus One. Indeed, the whole movie has an amateur-theatricals ambience. Burgess Meredith was given almost nothing to do, and spent his time offscreen regaling the cast with humorous yarns about his youthful bedroom adventures with Tallulah Bankhead and other Hollywood icons.

The saddest aspect of Godard’s King Lear is that it contains just enough of Shakespeare’s play to make the viewer long to be watching the original instead of Godard’s mangled take on it. The 150 or so genuine Shakespearean lines that Godard did weave in—spoken at random points in the movie by Meredith and Ringwald—included snippets from King Lear itself plus excerpts from other plays and the sonnets. Towards the end, Meredith reads the speech (from a script, as was Godard’s conceit) spoken in Shakespeare’s play by the shackled, half-mad Lear to the helpless Cordelia after their enemies, triumphant and sneering, have made them captives and marked them for death:

...Come, let’s away to prison.

We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage.

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down

And ask of thee forgiveness. So we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too—

Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out—

And take upon’s the mystery of things,

As if we were God’s spies....

Watching this, I thought: this is the real thing. Why didn’t Godard just make a straight-down-the-road movie out of the play itself, starring Burgess Meredith?

The answer is: Godard couldn’t. His devout and high-minded admirers—I’m looking at you, Richard Brody—cloak the movie in elaborate postmodernist deconstruction, as if it were really a film about the failure of language to express reality, or the failure of cinema to be more than a jumble of sounds and images, or the failure of artistic creation to mean anything. “The grand metaphorical conceit of Godard’s King Lear, albeit arch and puckish, is a project of vast aesthetic, quasi-comic ambition, in which Godard’s own comic role as an artistic shaman is central,” Brody writes in his book.

Godard was too lazy and too self-involved to make anything except an amateurish farrago. Much less did he possess the self-discipline or professional discipline of Hitchcock or Rossellini or any of the other great directors he admired. He couldn’t film an actual scene from Shakespeare to save his life. He could only work in bits of whimsy—some of them clever, some merely clever-ish, and some just plain tedious and embarrassing—and then induce or force other, more talented people to act them out, on the strength of his presumed genius. This worked pretty well (although not as well as his admirers think) when the Godard brand was fresh and new and moviegoers wanted a break from conventional film narratives and conventional techniques. A mere 25 years later, it was very worn indeed. And now, 37 years after that, who but a film-studies grad student hunting for a dissertation topic wants to sit through King Lear?

Ah, but Godard’s final film, Le Livre d’Image (2018)! Here I discovered something new: a Godard film that I could enjoy, at least until the end. That was because it is, for the most part, exactly what it purports to be: a montage of images—clips from films, 142 of them, that Godard cherished, spliced together with genuine artistry and blissfully little of the director’s annoying voiceover. The clips rolled by: beautiful and evocative and sometimes funny (the shark from Jaws). Some of the movies were familiar classics (Citizen Kane, Napoleon, Alexander Nevsky, Los Olvidados, La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc, Roma Città Aperta), while others reflected Godard’s idiosyncratic tastes (Cecil B. DeMille’s 1935 The Crusades, starring Loretta Young as Richard the Lionheart’s wife, but no Cleopatra or Ten Commandments). Quite a few of them were from Godard’s own oeuvre, which looked far more interesting in brief clips than they had when I watched them in full. The experience rolling over me was hypnotic: I briefly fell asleep, but that, in some way, seemed to be the point.

I grasped, dimly, that Godard was trying to make a moral observation about cinema’s inability, despite its apparent immediacy as a medium, to come to terms with the horrific mass slaughter that technology enables: the Holocaust and the nuclear bomb. And because this was Godard, Israeli–Palestinian confrontations are presented with a distinct anti-Israeli slant (one wonders—and dreads to think—what he would have made of the current disaster in Gaza had he lived to see it). In fact, Godard dedicated the last, longest, and most didactic of Le Livre d’Image’s five numbered sections to what he called the “Arab world.”

This section seemed to be an effort to create a “history of cinema” for the Mideast and North Africa (along with Islamic Central Asia, which apparently counted as “Arab” for Godard) that would be a counterweight to the rest of the movie’s focus on the filmic output of Europe and North America: clips from films made in Egypt, Morocco, Afghanistan, and Iran together with footage of ISIS attacks, other footage that Godard had shot in Tunisia and elsewhere in 2016, and voiceover excerpts from the French-Egyptian writer Albert Cossery’s 1984 novel Une Ambition dans le Desert. The novel seems to have little to do with the screen images, except, perhaps, to function as an objective correlative of the disjunction between the written word and the pictures that celluloid captures. That’s presumably a telling observation, but it looked tautological to me, and I was as relieved when the film wrapped up, just as I usually was after prolonged Godard exposure.

XII. A Mind Unreeled

Jean-Luc Godard, like King John in A.A. Milne’s poem, was not a good man. He was a case study in the dark triad staples of narcissism, Machiavellian manipulation, and sociopathy. His indifference to the modesty of children and to such obvious moral bright lines as the incest taboo showed a failing of affect that manifested itself in his mistreatment of nearly everyone who at one time or another extended him kindness and support: his father, his grandfather, André Bazin and his widow, Georges de Beauregard, and Jean-Pierre Gorin. His public nastiness at the mention of Truffaut’s name lasted until the end of his life.

Nor did he treat Anna Karina kindly as the years passed. When the two found themselves together in a surprise televised reunion engineered by French talk-show host Thierry Ardisson in 1987, Godard announced in front of the cameras that he had modelled their relationship on those of past auteurs and their leading ladies—Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth; Joseph von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich; Jean Renoir and Catherine Hessling—and while this had allowed him to make films, the relationship itself “never worked.” Visibly distressed, Karina excused herself from the set in tears as Godard sat grinning on the sofa. When she recomposed herself and returned a few minutes later, he is said to have told her, “You don’t come on TV to cry.”

Even Richard Brody got the brush-off when he spoke to Godard for the New Yorker in 2000—the only interview that Brody was ever able to secure with his idol. After a pleasant talk and then dinner together, Godard invited Brody to come by his office the next morning. But when Brody arrived, he found the curtains drawn and a note from Godard taped to the door saying he couldn’t continue the interview because their conversation the previous day hadn’t been “a real discussion.” And I wonder how Anne-Marie Miéville felt when Godard announced that he intended to make her a widow at a Swiss suicide clinic.

Bad people can create great works of art—we have Caravaggio and Roman Polanski as witnesses to that. Yet it is hard to locate the great works of art in the towering haystack of slapdash pictures that Godard produced year after year. You can argue, as Brody does in his book, that Godard’s “increasingly intellectualized range of concerns and abstract connections” meant that he operated at too high a level for most people to understand. His films are simply “too demanding” in Brody’s view. But it is also possible that Godard was simply a massive fraud, playing for decades on the intellectual aspirations of film critics and film historians themselves.

Godard genuinely loved movies in a touching and childlike way that he was simply unable to turn into rewarding art of his own. He also genuinely loved—and this was paradoxical for a standard-bearer of disruption—the old high culture of the West that the rebels of the 1960s had kicked to the curb: the classical music, the canonical literature, and the masterpiece paintings that he casually dropped into his films like bits of allusive glitter. It was as though he was looking for something stable, some hint of a lost order that evidenced itself in the moral concerns that surface almost inadvertently in films like À Bout de Souffle and Vivre Sa Vie, his dabbling in Christian theology in Je Vous Salue, Marie, and in King Lear with its ringing Easter church bells.

📷 Jean-Luc Godard c 2000 pic.twitter.com/E6RSjSNYXP

— redball (@redball2) December 4, 2021

He just could not think of a way to present this material coherently. In a prescient 1966 essay on Godard for the New Republic, Pauline Kael—who was a fan, although later a disillusioned one—wrote: “Maybe he is attempting to escape from freedom when he makes a beautiful work and then, to all appearances, just throws it away. There is a self-destructive urgency in his treatment of themes, a drive toward a quick finish. Even if it’s suicidal for the hero or the work, Godard is impatient for the ending....”

“A madman,” G.K. Chesterton wrote, “is not someone who has lost his reason but someone who has lost everything but his reason.” There was an element of creeping insanity in Godard’s unreeling and splicing slices of film in Rolle for decade after decade. Perhaps he realized, at least toward the end, that the medium he had cherished and critiqued for so many years was actually dying (the French film industry is almost no more), and this generated a despair that he didn’t wish to live to handle. Everything was cinema to Godard, but in the end there was nearly no cinema left.