Politics

What Is the Labour Party For?

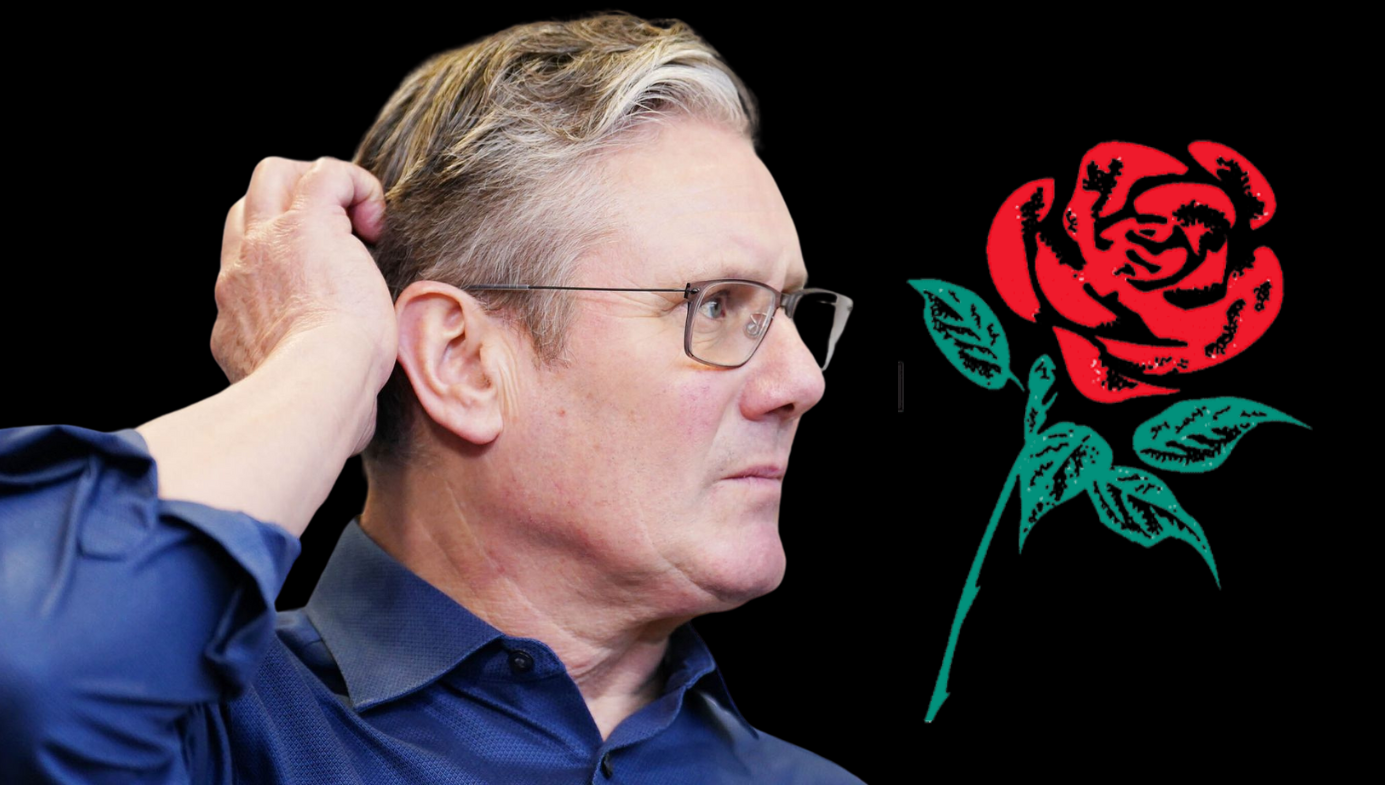

Sir Keir Starmer looks likely to become Britain’s next prime minister at a time when the democratic centre-left everywhere is facing a crisis of definition.

A review of Keir Starmer: The Biography by Tom Baldwin; 448 pages; William Collins (February 2024)

As Britain’s Conservative government plunges to new depths in the polls, the assumption hardens that the Labour Party will take over, sometime later this year or early in the next. The most recent poll forecasts a Labour majority of nearly 250 seats. This may seem like good news, even to citizens accustomed to voting Tory, since the governing party has entered such a febrile period that only forced retirement will permit the reinstatement of steady governance.

But that is not necessarily the case. Tony Blair’s New Labour government was ushered into office in 1997 with the promise that “Things Can Only Get Better” (from the D:Ream song that became the party’s electoral anthem). Today, however, the more modest (and possibly forlorn) hope is that “surely things can’t get any worse.” In a climate of growing cynicism, the belief that a better future might be crafted by political parties and governments is generally thought to be naïve. Only party people are prepared to trade in optimism, and in the current climate, such people are stripped of all credibility.

Notwithstanding the massive poll leads, the prospect of a Labour government simply doesn’t enthuse the British public. That, at least, is the message greeting canvassers on the doorstep. The party’s 61-year-old leader, Sir Keir Starmer, is certainly not about to set pulses racing, and its political programme is short on radicalism and long on caution. So, a Conservative government looks likely to be replaced by a small-c conservative one in progressive clothing.

Starmer has led the party since 2020, when he took over from Jeremy Corbyn, an anti-Zionist and “anti-imperialist” of the unreconstructed far Left, who spent his political life as a backbench agitator vigorously supporting regimes opposed to Western interests. Starmer was a senior figure in Corbyn’s shadow cabinet, but he has since made a show of purging the party of Corbynite policies and activists—including Corbyn himself. He has made an even larger show of stamping out the antisemitism that flourished under Corbyn’s leadership, but that is proving more difficult to extirpate as pictures from Gaza prompt growing horror, now visited on diaspora Jews (who, more often than not, are themselves horrified).

During his leadership campaign, Starmer pledged that the party would remain on the “broad Left” under his stewardship, but he soon reversed course, brusquely explaining that the economy was too weak and international conditions too turbulent for radicalism. His house-cleaning has made it seem as though he is spending more time fighting with the far-Left than attacking the Conservatives and popularising his own policies.