Art and Culture

Mutual Friends: The Adventures of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins

A charming exhibition at London’s Charles Dickens Museum provides a fascinating glimpse into the private lives of two great English writers.

In February 1837, budding writer Charles Dickens moved into London’s 48 Doughty Street with his wife and six-week-old baby. In just two furious years, he would author The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and Nicholas Nickleby—three imperishable novels that would grip Victorian audiences and propel the young writer to literary superstardom.

Today, the Doughty Street address is the site of the Charles Dickens Museum, where a new exhibition opened on November 15th devoted to Dickens’s long friendship with fellow author Wilkie Collins. The two men first met through their shared interest in amateur dramatics. Dickens, says curator Emma Harper, had “used acting to bring his characters to life. We have a note from his daughter Mamie, recalling her father frantically scribbling away, writing, and then jumping up, standing in front of a mirror and acting something out—really becoming the character, trying to get their voice and facial expressions. Acting is always a very big part of Dickens’s writing and life.”

Dickens and Collins met in 1851 when they both performed in Not So Bad As We Seem, a play written by their mutual friend Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The two men came from very different backgrounds. "Wilkie came from a stable middle-class home,” Harper says. “At 13, he even goes to Italy on a family holiday, whereas 11-year-old Dickens worked at a rat-infested blacking factory that traumatised him for life. He had lived in 22 homes before he moved to Doughty Street.” By the time they met, Dickens was 12 years older than Collins and already an established writer.

Still, differences in upbringing and age notwithstanding, the two men quickly forged a mutually rewarding, two-decade friendship that would endure until Dickens’s death in 1870—traveling and writing together, and even becoming linked by family marriage. The exhibition marks the bicentenary of Wilkie Collins’s birth on January 8th, 1824, and displays a huge body of work produced by the two authors during their acquaintance, from articles published in Dickens’s Household Words magazine to novellas and plays such as The Frozen Deep and The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices. In addition, visitors can see notes from their Tavistock House theatre plays and read some revelatory correspondence.

A letter Collins wrote to his mother in 1852 shows just how awestruck he was at the start of the friendship. Written while he was holidaying with Dickens, it reads: “If good ideas are as infectious as bad, the end of [my] novel, written in this house, ought to be the best part of it.” Letters from Dickens to Collins reveal his first impressions of the latter’s breakthrough novel The Woman in White, discussions of possible cures for writer’s block, and some striking literary reflections.

There are also recollections of amusing misadventures, such as a 1857 letter that recounts a joint trip to Cumberland. “Think of Collins’ usual luck with me!!!” writes Dickens. “It rained in torrents, as it only does rain in a hill country the whole time.” Realising that their guide was lost and their compass was broken, “we took our own way about coming down, struck and declared that the guide might wander where he would, but we would follow a water-course we lighted upon, and which must come at last to the River. This necessitated amazing gymnastics, in the course of which performances, Collins fell into the said watercourse with his ankle sprained.” Dickens ended up carrying his friend to the inn. (This incident would later appear in The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices.)

Another letter shares humorous details of a holiday he and Collins took together in Italy, during which they began a moustache-growing competition. “The moustaches,” Dickens wrote, “are more distressing, more comic, more sparse and meagre, more straggling, wandering, wiry, stubbly, formless—more given to wandering into strange places and sprouting up noses and dribbling under chins, than anything in that nature ever produced, as I believe, since the Flood.”

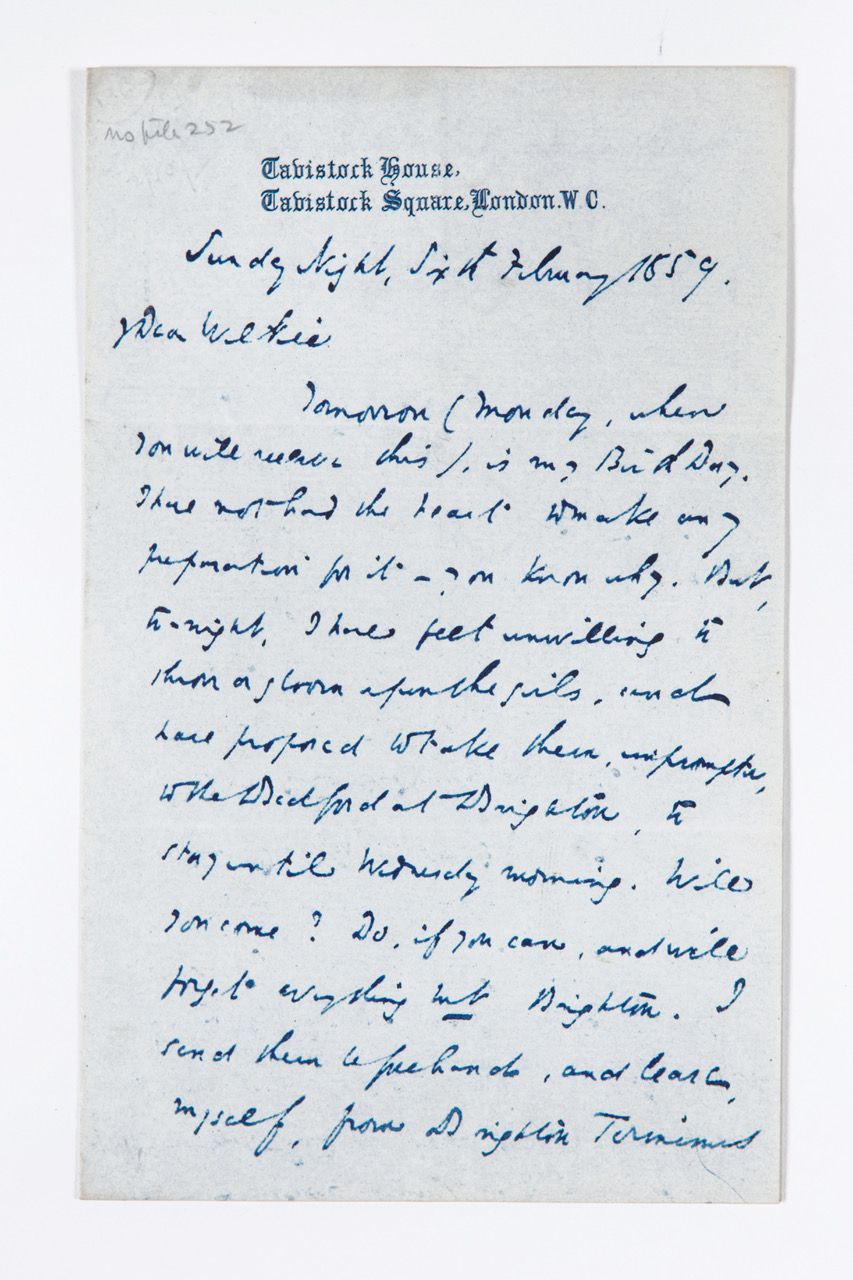

“We don’t talk that much about adult friendships in the modern world,” reflects Harper, “particularly male ones. But in the Victorian era it really was crucial. Charles and Wilkie helped each other through hard times and even shared intimate secrets.” On February 6th, 1859, the day before his birthday, Dickens wrote to tell Collins of his painful separation from his wife Catharine, the mother of his ten children: “I have not had the heart to make any preparation for it, you will know why.” He invited Collins to Brighton in the hope that his friend could cheer him up.

“We know that Collins and Dickens were very often frank with each other and that they cared for each other,” notes Harper. “In a letter to someone else, Wilkie writes: ‘No one apart from my mother has ever understood me as well as Dickens.’ Towards the end of his life, he writes: ‘We were as fond of each other as men could be, nobody (my poor dear mother excepted, of course) felt so positively sure of the future before me in Literature.’” In January 1863, Dickens wrote to Collins from his hotel in Paris, and confided that his absence was occasioned by a visit to see Ellen Ternan, with whom the then-married Dickens had begun a relationship. It was a secret that Collins guarded closely, and the affair only came to light after his death.

“Of the hundreds of letters Wilkie wrote to Charles, only three are known to survive,” explains Harper. “On the 3rd of September 1860, Charles held a bonfire at Gad’s Hill, burning 20 years’ worth of letters. He was a great celebrity, and worried about how he would be portrayed after his death. Even though we only have one side of the correspondence, you can tell how close Charles and Wilkie were.”

The exhibition offers a fascinating glimpse into the lives of two great writers, whose companionship rested on mutual trust and harmonious literary collaboration. “At the start of their literary collaboration, they might write different sections or write from different viewpoints,” explains Harper, “but their last collaborations such as No Thoroughfare are written together, so it is impossible to tell which paragraphs are Charles and which are Wilkie. There’s a letter from Wilkie that literally says ‘we wrote the last act side by side at Dickens's desk in Gad’s Hill.”

When Dickens left Household Words to start his new magazine All the Year Round, he brought Collins with him, sometimes toning down articles he thought might offend his readers’ middle-class sensibilities. “It is important to consider the context and the very different times,” says Harper. “People heavily consumed printed matter and both were very keen to broaden [their] readership, to be aware of who was reading their novels and make them as available as possible. Many families wouldn’t have been able to afford a book but they could afford a journal or a monthly.” Dickens and Collins knew they were writing for a largely illiterate public, she says. “Quite often—and this is where the performance element comes back in—these works would have been read out by one member of the family who could read to a larger, illiterate group where not everyone could read.”

In 1872, two years after Dickens’s death, John Forester’s biography, The Life of Charles Dickens, was published. Collins’s own copy contained handwritten notes he made about his late friend’s works. The book was sold in 1890 and its current whereabouts are unknown, but the notes have been recorded. Of Oliver Twist, Collins noted: “The one defect in that wonderful book is the helplessly bad construction of the story. The character of Nancy is the finest he ever did, he never afterwards saw all sides of a woman’s character, saw all round her. That the same man who could create Nancy created the second Mrs Dombey is the most incomprehensible anomaly that I know of in literature.” Collins considered David Copperfield to be “incomparably superior to Dombey,” while of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Dickens’s last novel, he wrote: “Cruel to compare Dickens in the radiant prime of his genius with Dickens’s last laboured effort, the melancholy work of a worn out brain.”

Dickens’s old writing desk is the exhibition’s main attraction. Other items of interest to fans include a charming 1864 photograph taken at Dickens’s Gad’s Hill home, showing him lying on the grass relaxing with family and friends, including Collins. A clock from the Gad’s Hill home is also on display at the museum along with Dickens’s letter to the clockmaker:

Since my hall clock was sent to your establishment to be cleaned it has gone (as indeed it always had) perfectly well, but has struck the hours with great reluctance, and after enduring internal agonies of a most distressing nature, it has now ceased striking altogether. Though a happy release for the clock, this is not convenient to the household. If you can send down any confident person with whom the clock can confer, I think it may have something on its works that it would be glad to make a clean breast of.

Faithfully Yours,

Charles Dickens.

It is somehow reassuring to learn that even literary geniuses could become exasperated by the small inconveniences of daily life.

“Mutual Friends: The Adventures of Charles Dickens & Wilkie Collins” can be seen at the Charles Dickens Museum until February 25th, 2024.