Politics

Kissinger and Cambodia

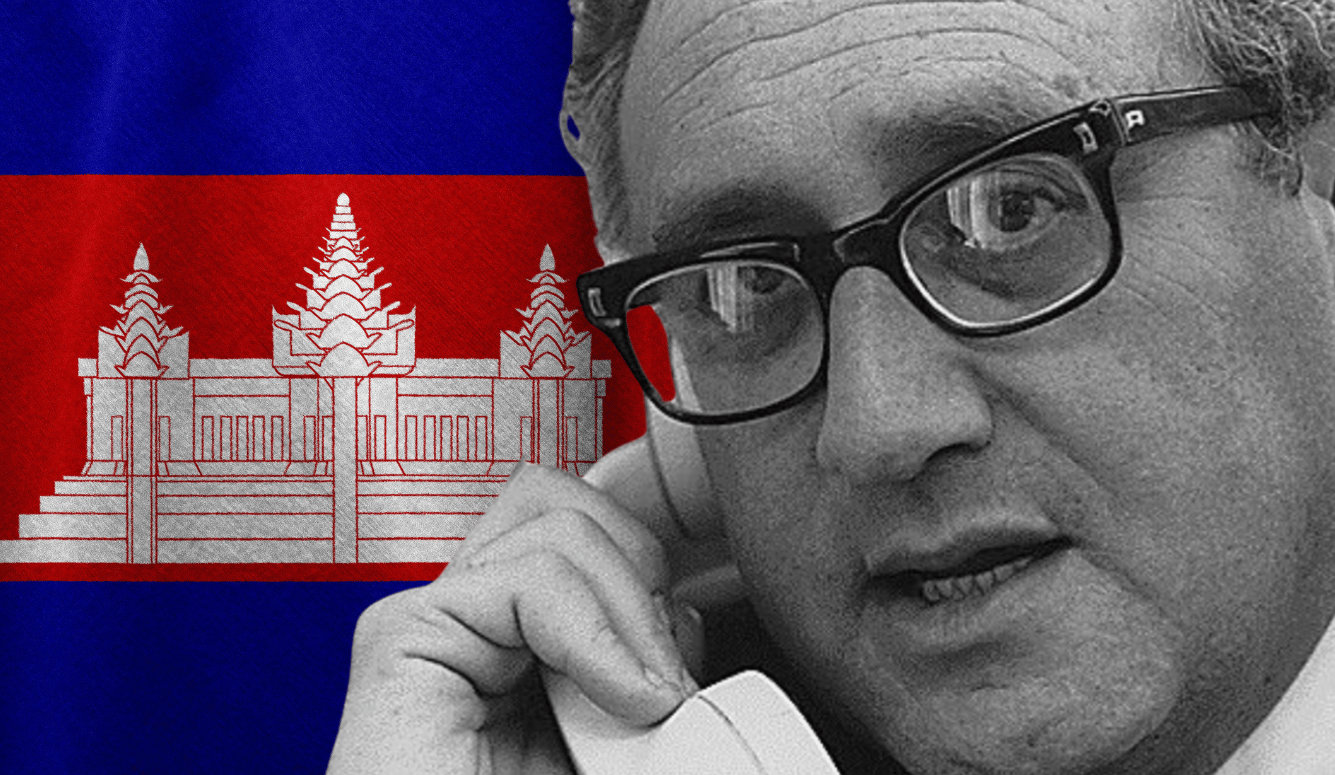

Henry Kissinger’s policies influenced Cambodia’s fate, but they alone did not cause the rise of the Khmer Rouge.

“Once you’ve been to Cambodia, you’ll never stop wanting to beat Henry Kissinger to death with your bare hands,” wrote the late celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain in a 2001 memoir. That line was widely re-shared on social media amid jubilant reactions to Kissinger’s death on November 29th. Wrapped up in Bourdain’s vengeful quote is the commonly accepted idea that the US bombing of Cambodia during Kissinger’s tenure as National Security Advisor (and later Secretary of State) led to the destabilization of a country described by its then-leader Prince Norodom Sihanouk as an “island of peace.” As a result, a neutral nation was forcefully sucked it into the maelstrom of the Vietnam war.

The conclusion that usually follows from this version of events is that the US bombing campaign killed hundreds of thousands of Cambodians and propelled the Khmer Rouge’s murderous regime to power. Therefore, Kissinger and Nixon bear significant responsibility for the crimes against humanity and genocide perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge during their four-year regime (1975–79). But this reading of a long and complicated period neglects to tell most of the story. Picking a page near to the end of a book and saying, “I guess we will just start here” is not good way to evaluate history.

What follows is not an attempt to absolve the decisions and policies of the Nixon administration, nor to deny the destruction and death that befell Cambodia during that period. Nevertheless, the story of the Cambodian tragedy is more complicated than the morality play favored by some journalists, media outlets, scholars, and celebrity chefs allows. At a minimum, many of the accepted “facts” used to support a straightforward narrative of US culpability require an asterisk—because, as we shall see, there is plenty of blame to go around.

I. Vietnamization and Its Discontents

Nixon took office in January 1969, at which point he assumed responsibility for resolving the problem of US involvement in Vietnam that had already been passed from Eisenhower to Kennedy to Johnson. The quagmire in Southeast Asia had destroyed his predecessor and Nixon inherited an unappetising menu of options. More than 500,000 US troops were then stationed in South Vietnam, and they were being killed at a rate of around 200 per week at a cost to the US taxpayer of more than $30 billion a year. Domestic support for the war had cratered.

Nixon and Kissinger believed they could end the Vietnam war in a way that preserved US credibility. This would be accomplished by a “Vietnamization” of the conflict—reducing the number of US troops and bolstering the South Vietnamese administration and military. At the same time, in an effort to discourage America’s communist enemies from perceiving the troop drawdown to be a sign of weakness, Nixon and Kissinger turned their gaze to the eastern border of Cambodia. Over the last decade, a system of bases and supply routes had been established there by the Vietnamese communists to support their war effort against the US-backed Saigon regime. There was even credible evidence of a kind of “Viet Cong Pentagon” hidden away somewhere in the sparsely populated jungles on the border, known as COSVN (Central Office for South Vietnam).

Nixon and Kissinger hoped that extensive bombardment of these bases would disrupt the communist war effort, allowing for the withdrawal of US troops, consolidation of the Saigon regime, and peace initiatives with the North produced by bringing pressure to bear on Moscow. They also believed that an awesome display of military power, far exceeding anything employed by Johnson, would project an image of Nixon as a hawkish “madman” who would frighten the communists into seeking a resolution. These efforts did not produce the intended results.

From March 1969 to May 1970, the US conducted a bombing campaign of communist positions in Cambodia codenamed “Operation Menu.” Kissinger and others within the Nixon administration responsible for designing this strategy deemed it illegal enough that they decided it must remain secret. They were also keen to avoid the domestic outcry that would doubtless be produced by perceptions that they were spreading the war beyond Vietnam. So, they circumvented Congress, leading government officials, and most of the established procedures that would usually be required to approve military action of this kind.

While the illegality of this decision is not in doubt, the military goals are less easy to criticize. Ben Kiernan, an eminent historian of Cambodian history, has suggested that bombardment of the Cambodian border had begun as early as 1965, under the Johnson administration. Reconnaissance missions and CIA operations strongly indicated that the Vietnamese communists were indeed making use of “sanctuaries” across the Cambodian border. One of these missions—codenamed “Operation Vesuvius”—even provided Cambodia’s royal leader with photographic evidence of this violation of his country’s territory by late 1967. His refusal to put an end to this behavior called claims of Cambodian “neutrality” into question.

II. Sihanouk’s Balancing Act

During the Vietnam war, Western journalists who sojourned in neighboring Cambodia tended to describe a charming and peaceful nation, and the capital city of Phnom Penh was known as the pearl of Southeast Asia. Since the decolonization of French Indochina in 1954, Cambodia had embraced independence, and by the early 1960s, it appeared to be flourishing. The country’s charismatic prince, Norodom Sihanouk, insisted that Cambodia was “neutral” in the conflict raging on its doorstep, and the political “balancing act” that this neutrality required was widely praised at the time.

However, as early as 1954, reports began to emerge that Sihanouk had made secret arrangements with an official of Ho Chi Minh’s army in the wake of the Geneva Accords that split Vietnam at the 17th parallel. These arrangements allowed limited numbers of Vietnamese communists to operate clandestinely in certain areas on the Cambodian side of the border. This would assist the struggle against South Vietnam, in return for which, Sihanouk was assured that Vietnamese communists would not interfere in Cambodian affairs.

Historians David Chandler and Philip Short have suggested that Sihanouk was stuck between a rock and a hard place. But by the mid ’60s, he was far more comfortable on the communist side of the divide—internationally, at least—and with good reason. In 1959, an effort to remove him from power had failed (the CIA-condoned “Dap Chhuon Plot”) and he had survived an assassination attempt that implicated the Diem family leading South Vietnam. He cut off American aid and diplomatic ties in 1963, and over the next few years, he increased ties with China and allowed more Vietnamese communists use of the Cambodian border. This assistance included the supply routes of the Ho Chi Minh trail, established bases, and a regular supply of Chinese materiel overland from the western coastal port of Sihanoukville.

Forced to choose between the Americans and the communists, Sihanouk (correctly) judged that the former were more likely to leave first, and he placed his bets accordingly. He publicly recognized the North Vietnamese National Liberation Front (NLF or Viet Cong) diplomatically and made deals with them in private. At the same time, however, he strenuously denied the existence of NLF troops on his territory—the “sanctuaries” Nixon would later identify. This was what became known as Sihanouk’s “balancing act,” or perhaps somewhat more confusingly, his policy of neutrality.

The turning point arrived in late 1967, when Sihanouk became concerned that his communist allies were not, in fact, to be trusted. The Cultural Revolution in China had caused sympathetic Sino-Khmers to criticize his government, and his Chinese and Vietnamese friends seemed to be unable or unwilling to stop a native Cambodian revolutionary movement—the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) also known as the Khmer Rouge—from rising against him.

I do not disagree with those historians who argue that Sihanouk’s actions were rational in the face of serious threats—he had managed to keep his country out of the war for years. But he had also made consequential concessions to the Vietnamese communists, and those concessions assisted the NLF guerrillas and the regular North Vietnamese Army (NVA) in their war effort in South Vietnam, which included attacks on US soldiers. Those who now argue that Kissinger and Nixon were unjustifiably bombing a stable and neutral nation, should at least acknowledge that Cambodia wasn’t really neutral at all. Nor was it especially stable.

III. Destabilization

The secret US bombing campaign of isolated targets on Cambodian territory began in March 1969, two months after Richard Nixon took office. But by this time, the notion that the country remained an “island of peace” or the “pearl of Southeast Asia” belied a grim reality. As historian Milton Osbourne points out in his biography of Sihanouk, many popular accounts of the prince’s regime, which lasted from 1955 to 1970, are uncritically sympathetic, “whether for personal or ideological reasons.” But Osbourne also speculates that the incompetence and brutality of what followed his rule have protected the Sihanouk regime from the rigor of historical or journalistic scrutiny that it properly deserves.

Prince Sihanouk was the king of Cambodia until 1955. In Cambodia’s first contested elections, stipulated by the Geneva Accords in 1954, he had abdicated the throne and created his own party. The Sangkum party—a hodgepodge of socialist and nationalist ideas—sought to drain the support of the other established political parties in the country. Suffice it to say, this 1955 campaign was neither free nor particularly democratic. Sihanouk, king in everything but name, was able to capitalize on the aura of the Cambodian monarchy, and did not hesitate to employ violence and intimidation against the unconvinced.

Over the next decade, the prince systematically eroded any chance of genuine political pluralism. The upshot was a dysfunctional government that relied on Sihanouk’s prestige, power, and connections to get anything done. Opponents on both sides of the political spectrum were routinely demeaned and abused. One by one, political parties with far more legitimacy than his own crumbled under his repression, including the public face of the Cambodian communist movement. By the mid ’60s, the communists had been stripped of political participation and forced completely underground, their leaders threatened with imprisonment or worse. And so, they turned to armed struggle. By 1963, the future leadership of the Khmer Rouge regime—including Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Nuon Chea, and Son Sen—were all either hiding with the Vietnamese communists in the jungles on the border, or they were operating clandestine networks of resistance around Cambodia.

During the years leading up to the Nixon presidency, the Cambodian economy was in free fall due to mismanagement, corrupt governance, and failed nationalization programs. Vietnamese were purchasing Cambodia’s largest export (rice) on the black market, and the country’s economic woes were compounded by Sihanouk’s decision to halt US financial and military aid in 1963. Perhaps tired of running the country by himself, Sihanouk had begun spending an inordinate amount of time writing, producing, editing, and directing films. While the country fell to pieces, he established a film festival at which his movies competed in their own category to ensure a golden statue at each annual event.

Then, in April 1967, as a conservative cabinet was elected (the first time that Sihanouk had not bothered to handpick every cabinet member), the country embarked upon a rice surplus requisitioning scheme intended to prevent Cambodia’s largest export from falling directly into the hands of the Vietnamese communists. The “ramassage campaign,” as it was known, involved collecting produce directly from areas of the country where rice was most plentiful. Farmers were forced—sometimes at gunpoint—to sell to the government at a rate much lower than what they had obtained from the black-market operations supplying the war effort in South Vietnam.

Consequently, a peasant uprising—encouraged by local communists but not necessarily led by them—erupted in the Battambang region. The murder of several government troops by farmers, and the militia attacks that followed on government outposts, would become known as the “Samlaut Uprising.” In response, Sihanouk unleashed a campaign of repression. The poorly equipped peasant rebels, numbering perhaps in the hundreds, were subjected to artillery fire and bombardments from the Cambodian airforce. Local militia groups of pro-government supporters were assembled to “hunt the Reds” and promised a bounty for every communist head they brought back.

Unsurprisingly, some of the more enterprising members of these militias soon realized that they could produce anyone’s head and claim that it had belonged to a rebel. Historian Elizabeth Becker records that severed heads were displayed on pikes around the Battambang region to reinforce the government presence there. There were also reports of truckloads of severed heads arriving in Phnom Penh to prove to the government that the army was achieving its aims.

This was Cambodia, 1967—two years before Nixon and Kissinger began bombing jungle targets on the border with Vietnam in the “Operation Menu” campaign. While the country’s head of state was moonlighting as a film director and jazz musician, his troops and associated militias were slaughtering a thousand people for rising against him. And now that his political opponents—on the Left and the Right—had been prevented from participating in the political process, they were plotting an insurgency to take the country from their former King. This was not a stable country.

None of this means that the Vietnam war played no role in Cambodia’s destabilization. Many historians have argued that, were it not for the war in Vietnam, none of the issues discussed here would have developed as they did. But the war was not started by Nixon and Kissinger, and they had no hand in the internal political chaos into which Cambodia had already fallen before they took office.

IV. Paving the Way for Pol Pot

A BBC article published after Kissinger’s death includes this sentence: “Many also say that another consequence of Nixon and Kissinger’s bombing campaign was that it helped pave the way for one of the worst genocides of the 20th century.” This claim is at the heart of the argument that Henry Kissinger was responsible for the rise of the Khmer Rouge, and by implication, for the deaths of 1.7 million people who perished at the hands of Pol Pot’s communist regime between 1975 and 1979. However, the words “helped pave the way” are being asked to do a lot of work here.

By 1968, a full year before Nixon took office, the Communist Party of Kampuchea had already delivered on its promise of armed struggle against the Sihanouk regime. Having visited Hanoi and Beijing in the years prior, Pol Pot had become convinced that these nominal allies were standing in the way of his movement. Sihanouk’s alliance with the Vietnamese and Chinese communists meant that his removal by a native communist movement risked jeopardizing the larger strategic aims of both parties. As long as Sihanouk was in power, the Vietnamese could get their supplies from China, and count on a degree of autonomy as they used the border regions as a sanctuary from which to attack South Vietnam. To borrow the titular phrase that William Shawcross used in his book on the history of this era, it wasn’t just Nixon and Kissinger who considered Cambodia to be a “sideshow.” The Vietnamese had more or less invented Cambodian communism in the 1940s and early 1950s as a means of facilitating their independence from the French. Similarly, the People’s Republic of China had been using a Cambodian communist movement as a kind of potential counterweight to future domination of the region by an allied bloc of Soviet and Vietnamese.

The growing distrust that Sihanouk felt for his communist allies caused him to look back toward the US to continue his “balancing act.” In January 1968, Sihanouk met with US ambassador Chester Bowles, and although the details of their discussions are still contentious, it now seems clear that Sihanouk tacitly (and privately) acknowledged a Vietnamese communist presence on his territory. In a characteristically duplicitous move, he indicated that, since he could not stop the Vietnamese from crossing over to his side of the border, he couldn’t stop the US from attacking them there either. This conversation would later be considered a warrant for US “hot pursuit” of Viet Cong forces in Cambodia. More controversially, it would also be invoked by Kissinger among his justifications for the bombing campaign that was to follow.

That January was a busy month in the history of Cambodia. On the 18th, against the advice of the Chinese and Vietnamese, Pol Pot’s embryonic army attacked an isolated government outpost in the west of the country. Although the operation could hardly be described as a stunning success, the insurgents did manage to procure some weapons. They then launched a nationwide campaign of similar skirmishes. Following the blueprint of “People’s War” promulgated by Mao and employed by the communist rebels in South Vietnam, the CPK waged a guerrilla war against Sihanouk—something that the prince quickly realized was the outbreak of the Cambodian civil war.

January also saw the launch of the Tet Offensive in Vietnam—a massive attempt by the communists to overwhelm the South Vietnamese government and force the US into negotiations. This was done by massing their forces in Cambodian territory in the months leading to their attack. Sihanouk’s worries about the implications of his deal with the Vietnamese communists were now compounded by his inability to bring the Khmer Rouge to heel. Pol Pot and the rest of the group’s leadership had been living in border encampments until 1966, but they had subsequently moved further into the northeast, to the mountainous jungle of Rattanakiri.

Among the ethnic minorities living in Cambodia’s highland areas—such as the Jarai, the Brao, and the Kachak—the Khmer Rouge found allies sympathetic to their struggle against the Sihanouk regime. These tribes represented a romantic version of the “commune” in “communism,” living without money or markets, and the CPK recruited extensively from these peoples. Some of these recruits remained the leadership’s most trusted bodyguards throughout the Pol Pot regime. In 1968, as these groups began to participate in the armed struggle, Sihanouk condemned more than 200 of them to death without trial. “I do not care if I am sent to hell,” he shrugged. “I will submit the relevant documents to the devil himself.”

The policies enacted in Samlaut the previous year also returned during this period, including rewards for severed heads (along with rifles this time to ensure the dead were actually rebels) and aerial bombardment (using Chinese planes and munitions). According to Philip Short, in one particularly grim incident near Phnom Penh, two children thought to be communist messengers were apprehended by government troops and decapitated with jagged fronds from a palm tree. Violence escalated in a series of bloody attacks and reprisals, a cycle that began long before Kissinger and Nixon entered the picture.

V. A Fledgling Movement

In many of the articles published in recent weeks, much has been made of the “rise” of the Khmer Rouge between 1969 and 1975, prior to which they were merely a “fledgling” movement with fantasies of power. It is true that, by the start of 1968, membership of the Khmer Rouge only numbered around 5,000, and would balloon into tens of thousands by the time they achieved their total victory in Phnom Penh on April 17th, 1975. However, by 1967, even non-communist activists were joining the Khmer Rouge in their jungle camps and underground networks, as they were the only means of challenging Sihanouk’s authoritarian regime.

So, to what extent were Nixon and Kissinger’s policies to blame for the movement’s subsequent growth? Most historians now agree that the US bombing of Cambodia had only a marginal effect on dynamics within the country that had already assumed their own logic and momentum. But what historians conclude and what the general public and popular punditry believe rarely follow a similar trajectory.

The key juncture was the bloodless coup against Sihanouk in March 1970, led by General Lon Nol. There is no evidence that the CIA was behind this development, unlike the coup in South Vietnam seven years earlier. The most that we can say is that Sihanouk’s ouster was a happy accident for US onlookers, even though Sihanouk had re-established diplomatic ties with the US the year before and turned a blind eye as the Americans began bombing his country. Once out of power, Sihanouk was persuaded by the Vietnamese and Chinese to form a partnership with the Khmer Rouge and act as the coalition’s figurehead. In a speech delivered on March 23rd, he called on all patriotic Cambodians to flee into the jungle, where they would receive weapons and military training. The former head of state beseeching citizens to join a movement he had been trying to exterminate just weeks earlier was far more effective in driving recruitment than Operation Menu or the subsequent bombing of Cambodia until 1973.

Most historians would agree that the former King, who the majority of Cambodia's peasant population still held in quasi-god-like esteem, was the most critical driver for Khmer Rouge recruitment after 1970. I do not dismiss the accounts from people like Hun Sen (until recently, the leader of Cambodia for more than a quarter of a century) or Keng Gek Iev (better known by his revolutionary pseudonym “Duch”), who argue that the US bombing campaign from 1970–73 was exploited by the Khmer Rouge as a recruitment tool. However, the effects of the military intervention by the communist Vietnamese in the wake of the Sihanouk coup were far more important.

No longer shackled by the need to protect their alliance with Sihanouk, the Vietnamese quickly changed their long-maintained stance toward their Cambodian comrades in the CPK. They embarked upon a war against the new Cambodian government, and quickly overran its weaker army. Province after province rapidly fell to Vietnamese attacks, and training of what would become the Khmer Rouge army was now undertaken by their newly supportive Vietnamese allies. Once the Khmer Rouge was properly armed and trained, it was able to use violence to manipulate the populations under its control. This is what allowed the proto-state of Democratic Kampuchea to take shape as early as 1973. And once they had consolidated their grip over the country’s rural areas, there was no escape. By this time, an early version of the future regime’s terror apparatus had already been established. M13, a prison erected in the jungle, served as the “liberated” zone’s equivalent of Security Prison 21, a torture facility that would become the central node of the Khmer Rouge’s security machinery in Phnom Penh.

By 1975, the Khmer Rouge were capable of militarily defeating the Lon Nol regime, not because of US bombing but in spite of it. David Chandler argues that the US carpet bombing in 1973 actually postponed an even quicker Khmer Rouge victory. They had the Vietnamese communists to thank for their help to this point, but they would soon begin efforts to eradicate their influence and kill those they believed to be insufficiently committed to their cause.

VI. The Question of Responsibility

Sihanouk’s support and the assistance of the North Vietnamese were most critical to the Khmer Rouge’s rise to power. But even those developments do not account for the decades of incompetent and corrupt governance, during which the native Cambodian communist movement spread and consolidated its ideology. That is why the notion that the direction of Cambodian politics and history was determined by Nixon’s national security advisor is so historically illiterate. Cambodia was nothing like a stable “island of peace” by 1969, nor could Sihanouk’s policy of “neutrality” realistically be described as such. The cracks in Sihanouk’s Cambodia were evident before a single American bomb was dropped on its territory.

Missing from all the articles about Kissinger and Cambodia is an acknowledgement that he and Nixon were the inheritors not the instigators of the mess in Indochina in which America was entangled. Three presidents, and the democratically elected politicians who supported them, had each passed a growing and more complicated problem to their successors, and each new administration had expanded America’s involvement and made a US retreat more difficult. They all worried about US credibility and sunk costs more than they did about the suffering of their own soldiers, let alone that of the Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians. Lyndon Johnson had been bombing “neutral and stable” Cambodia as early as 1965, so why does this not rate a mention in the indictments of Kissinger?

The Nixon administration continued and expanded upon the policies of its predecessors, and with the same goals in mind—to end the war and make America look strong. The callousness of US intervention in Cambodia, and the release of “death from above,” was certainly cynical. Kissinger himself saw the death and destruction that American was raining on Cambodia as a means to an end in South Vietnam. I have no quarrel with those who wish to denounce the Nixon administration for waging a duplicitous and deceptive campaign, nor should we exonerate them for the loss of civilian life to the bombing itself. But leaving out important details of Cambodian history and politics, and inflating estimates and statistics to concentrate the blame where it doesn’t belong is simply bad history.

Recent op-eds and essays about Kissinger’s role in this grim story have stated that more than 2.75 million tons of ordnance was dropped on Cambodia between 1965 and 1973. This figure is lifted from an article written by Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen in 2007. They later retracted that estimate, claiming that it was based on a mistaken technical analysis, and revised it down to around 500,000 tons. That is still a very large figure, but the number of articles that seem to prefer using the initial estimate is very interesting, mostly because it allows for extreme comparisons to bombing campaigns during WWII.

Similarly, articles referencing “hundreds of thousands” of Cambodians killed by Kissinger’s bombs seem to be conflating the death toll of the Cambodian civil war and estimates of US bombing casualties. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal’s “Expert Demographer Report,” a detailed statistical analysis of all the demographic and survey evidence of the Cambodian death toll prior to and including the Khmer Rouge regime, concludes that the number of deaths during the entire civil war was probably in the region of 250,000. So, it is hardly accurate to say that “hundreds of thousands of Cambodians” died during the bombing campaign alone.

The issue here is that there were different bombing campaigns. There was the secretive “Operation Menu” campaign that targeted isolated “boxes” on the Cambodian side of the border, and then there was “Operation Freedom Deal,” a fully formed carpet-bombing campaign that would end up covering much of the land. The latter was welcomed by a US-friendly regime concerned for its own survival and threatened by a nationwide communist insurgency. It is quite easy to condemn this too, as it is to condemn the foolishness of the entire US military project in Indochina. They were blinded by the imperatives of the Cold War. Belatedly, Kissinger and Nixon noticed the fissures between the USSR and PRC in what had previously been considered a communist monolith, and some of their wider policies would aim at these vulnerabilities. But in relation to Cambodia, they acted outside of the jurisdiction of the US government to try and achieve what they felt were the most important goals, and Nixon certainly felt the repercussions of this.

But in the most egregious cases, polemicists have sought to diminish the guilt of the actual perpetrators of Cambodia’s terrible crimes—the Khmer Rouge, who are not explicitly held accountable for the carnage they visited upon their own people in the name of their crazed doctrines. Instead, their responsibility is held to be somehow mitigated by a narrow and narcissistic preoccupation with Western guilt. Likewise, the actual supporters of the Khmer Rouge—the Vietnamese and Chinese communists who supplied them with everything they needed to take over their country—are reduced to marginal players in such discussions. It should not need to be said that Security Prison 21 was not an American creation. Nor was Pol Pot. Confusingly, US interference after Nixon would keep Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge from the rigours of international justice—and yes, the Chinese were implicated in that, too.

With Kissinger, we are left with a kind of vestigial culprit—a face upon which we can project the entirety of the American misadventure in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos; a man who somehow escaped the stocks and the bare hands of a late celebrity chef. The United States, that fearsome leviathan, creates evil, and evil begets more evil. The evil of the Khmer Rouge can therefore be explained as a product of our own sins. But history is just not that simple.

I will close with the words of someone who was actually there, in Cambodia, before Nixon, and before the arrival of Kissinger’s bombs. He was there under Pol Pot, and he was there afterwards. He saw what Sihanouk’s “island of peace” looked like, and what the island of horror looked like. Oscar-winner Haing Ngor, who portrayed Dith Pran in The Killing Fields, wrote in his memoirs about the regime he had suffered under, about the question of blame and its distribution:

It is a complicated story, going back many years. To begin with, France, our former colonial ruler, didn’t prepare us for independence. It didn’t give us the strong, educated middle class we needed to govern ourselves well. Then there was the United States, whose support pushed Cambodia off its neutral path to the right in 1970 and began the political unbalancing process. Once Lon Nol was in power, the United States could have forced him to cut down on corruption, and it could have stopped its own bombing, but it didn’t, until too late. The bombing and the corruption helped push Cambodia the other way, toward the left. On the communist side, China gave the Khmer Rouge weapons and an ideology. The Chinese could have stopped the Khmer Rouge from slaughtering civilians, but they didn’t try. And then there is Vietnam. Even in the 1960s and early 1970s, when the Vietnamese communists used eastern Cambodia as part of their Ho Chi Minh Trail network, they were putting their own interests first. They have always been glad to use Cambodia for their own gain. But sad to say, the country that is most at fault for destroying Cambodia is Cambodia itself. Pol Pot was Cambodian. Lon Nol was Cambodian and so was Sihanouk. Together the leaders of the three regimes caused a political chain reaction resulting in the downfall and maybe the extinction of our country.