Education

“There’s Nothing Mystical About the Idea that Ideas Change History”

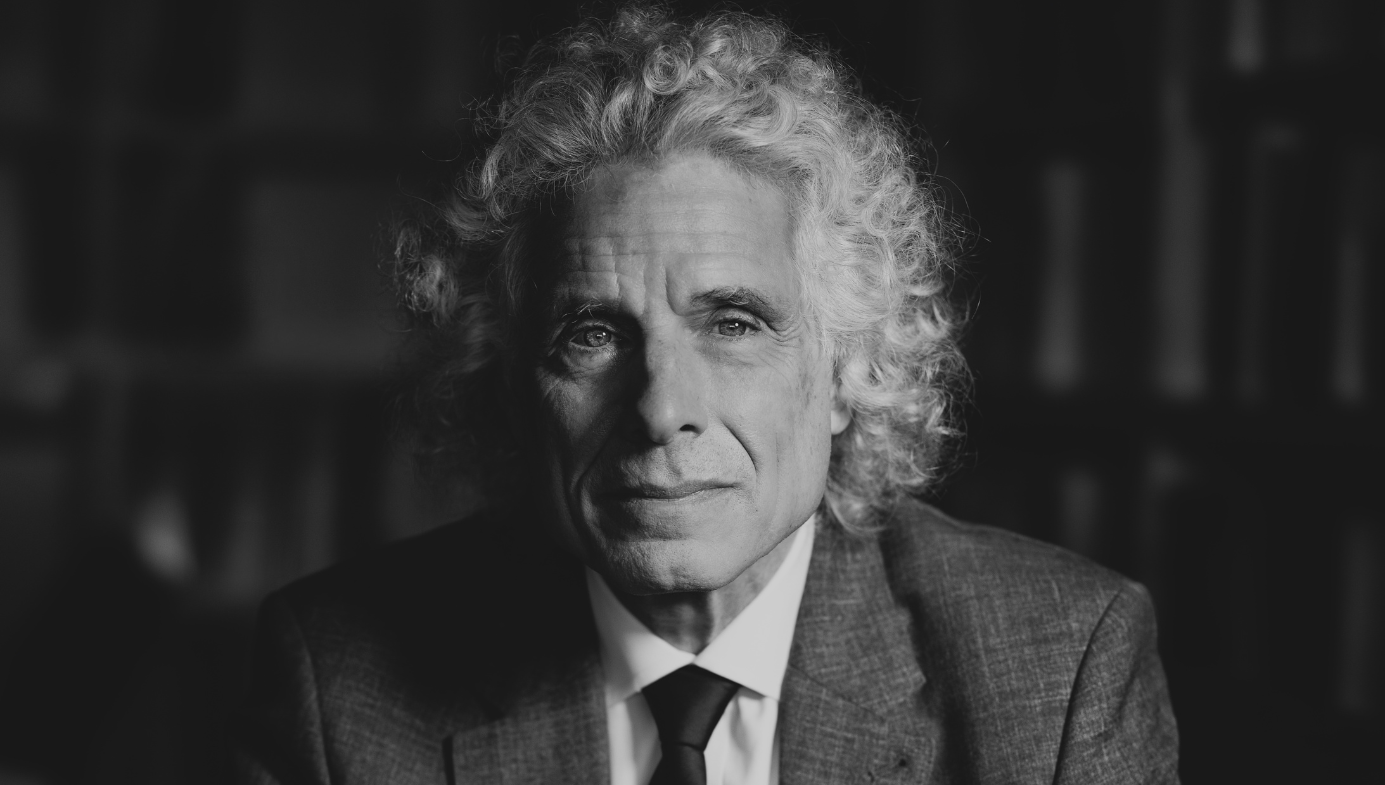

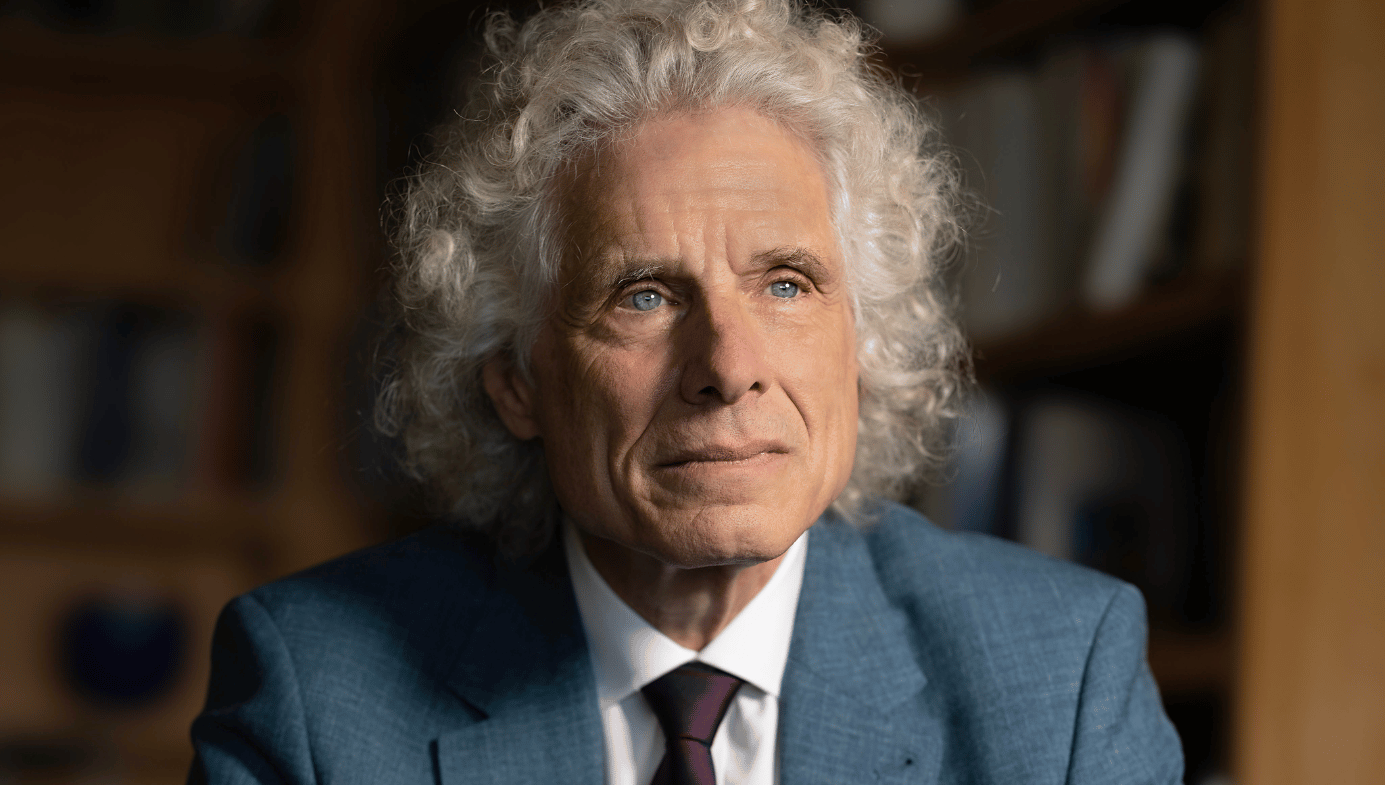

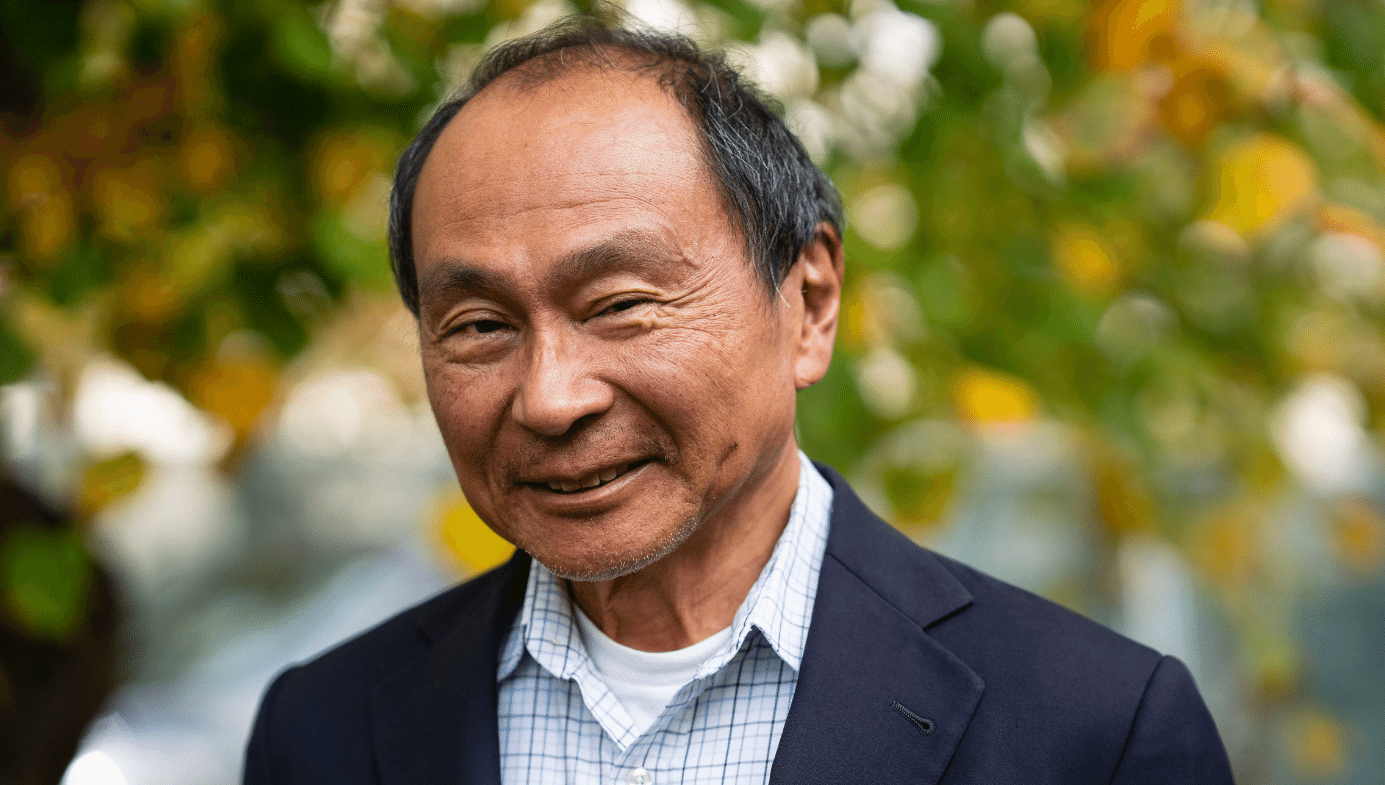

An interview with Steven Pinker.

Steven Pinker is an experimental psychologist and professor at Harvard, a prolific bestselling author, and one of the world’s most influential public intellectuals. He has written on subjects as diverse as language and cognition, violence and war, and the study of human progress. He draws upon his investigations of the human mind to help readers and audiences better understand the world those minds have built.

He has written a shelf of books, including How the Mind Works (1997), Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018), and most recently, Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters (2021). A recurrent theme of his books and research is that a richer understanding of human nature can help us live better lives.

I spoke to Pinker for Quillette and our lengthy discussion covers international politics, artificial intelligence, religion and secularism, the October 7th atrocities in Israel, the power of beliefs, meritocracy, college admissions, identity politics, Effective Altruism, the state of democracy around the world, and many other topics.

Quillette: In Enlightenment Now, you discuss the importance of “norms and institutions that channel parochial interests into universal benefits.” Jonathan Haidt says the nation is the largest unit that activates the tribal mind, whereas Peter Singer says we are on an “escalator of reason” that allows our circle of moral concern to keep expanding. What would you say are the limits of human solidarity?

Steven Pinker: I agree that the moral imperative to treat all lives as equally valuable has to pull outward against our natural tendency to favor kin, clan, and tribe. So we may never see the day when people’s primary loyalty will be to all of Homo sapiens, let alone all sentient beings. But it’s not clear that the nation-state, which is a historical construction, is the most natural resting place for Singer’s expanding circle. The United States, in particular, was consecrated by a social contract rather than as an ethnostate, and it seems to command a lot of patriotism.

And while there surely is a centripetal force of tribalism, there are two forces pushing outward against it. One is the moral fact that it’s awkward, to say the least, to insist that some lives are more valuable than others, particularly when you’re face-to-face with those others. The other is the pragmatic fact that our fate is increasingly aligned with that of the rest of the planet. Some of our parochial priorities can only be solved at a global scale, like climate, trade, piracy, terrorism, and cybercrime. As the world becomes more interconnected, which is inexorable, our interests become more tied up with those in the rest of the world. That will push in the same direction as the moral concern for universal human welfare.

And in fact, we have seen progress in global cooperation. The world’s nations have committed themselves to the Sustainable Development Goals, and before that to the Millennium Development Goals. There have been global treaties on human rights, atmospheric nuclear testing, chlorofluorocarbons, whaling, child labor, and many others. So a species-wide moral concern is possible, even though it always faces a headwind.

Q: I know you’re hostile to the idea of a world government, but do you think we’re prioritizing global institution-building enough?

SP: No, not enough. Now, a true world government, in the classic sense of “government,” would have a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. It’s hard to imagine the whole planet agreeing to a single set of laws enforced by global police. Who knows what could happen in a century, but for now, there’s just too much, let us say, diversity. The other disadvantage of a world government is that any institution is implicitly held in check by the power of its citizens to exit—to move their capital or their bodies someplace else. With a world government, there is no someplace else, and that means there’s one less brake on the temptation to become totalitarian.

Q: The EU was once considered a radical project—Orwell dreamed of a Socialist United States of Europe, for instance. In his book Nonzero, Robert Wright noted that if you told someone 60 years ago that France and Germany would one day use the same currency, they would have asked, “Who invaded who?” Now the prospect of war in Western Europe is almost unthinkable. Why don’t we appreciate the magnitude of this achievement? And how can we make Enlightenment values and the institutions they created more politically inspiring?

SP: A great question. Partly it’s a negativity bias baked into journalism: things that happen, like wars, are news; things that don’t happen, like an absence of war, that is to say peace, aren’t. For the same reason, it’s harder to valorize and commemorate the fact that something no longer happens, like great-power war.

Occasionally there have been efforts to arouse quasi-patriotic feelings for transnational organizations, like public performances of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy presented as the EU anthem. When I was a child, there were efforts like the “Family of Man” photo project and the Expo ’67 World’s Fair in Montreal which celebrated the unity of the human species. Admittedly, not many people get a warm glow when they see the United Nations flag, though I do—my visit to UN headquarters as a child was a moving experience, and it was again when I returned to speak there as an adult, despite knowing about the many follies of the UN.

And for all its fiascoes, the UN has accomplished a lot. Its peacekeeping forces really do lower the chance of a return to war—not in every case, but on average. And members of the UN are signatories to an agreement that war is illegal, except for self-defense or with the authorization of the Security Council. Even though that’s sometimes breached, most flagrantly with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we have to remember that whenever there are laws there are scofflaws, but that doesn’t mean the laws are useless. The legal scholars Oona Hathaway and Scott Shapiro have argued that even though the outlawry of war did not eliminate war, it reduced it by making conquests no longer recognized by the community of nations. That is, if Russia holds onto territory taken from Ukraine, it cannot count on other nations recognizing the conquest—which is a big change from the practice of millennia, when the policy was “to the victor go the spoils.”

And the Millennium Development Goals, completed ahead of schedule, were just one of many UN efforts to measure and address problems on a global scale. It’s easy to be blasé about these aspirations, but as the civilization-spanning historian Arnold Toynbee observed, “The twentieth century will be chiefly remembered in future centuries not as an age of political conflicts or technical inventions, but as an age in which human society dared to think of the welfare of the whole human race as a practical objective.”

Q: The international-relations theory of Realism assumes that human progress (at least when it comes to the relations between states) is impossible. This is why Francis Fukuyama criticized it as the “billiard ball” theory of international relations—it assumes that state behavior will always be dictated by mindless, mechanistic forces like the distribution of power in the international system. What’s your take on Realism?

SP: As it happens, I recently debated John Mearsheimer, the foremost Realist theorist. “Realism” is a misnomer—it’s a highly unrealistic idealization of the relationships among states, barely more sophisticated than the board game Risk. It assumes that countries seek nothing but power and expansion, because the only defense against being invaded is to go on offense first. But this ignores the other ways nations can protect themselves—like Switzerland, the porcupine of Europe. It’s also unrealistic about the psychology of leaders. It attributes to all leaders all the time a motive that some leaders have some of the time, namely, territorial aggrandizement. It’s a theory of Putin now, but not all leaders are Putin. Many countries are perfectly content to stay within their borders and get rich through trade. The Netherlands once had an empire, but the Dutch are not seething to rectify this historic humiliation and annex Belgium or reconquer Indonesia. Likewise, Germany could probably conquer Austria or Slovakia or Poland, but in today’s world, why would it want to? What would it do with them? Why not just trade goods and tourists? Who cares about the number of square inches of your color on a map? So expansion is not a constant thirst of all leaders.

And as Christopher Fettweiss and others have pointed out, the theory of Realism was falsified by events since the end of the Cold War. So-called Realism predicted that large states always seek to maximize their power and aggrandize their preeminence, but the Soviet Union voluntarily went out of existence. Realists predicted that a hegemon would inevitably rise up to balance the United States, so that by the beginning of the 21st century, some other country, probably Germany, would arm itself to become as powerful as the United States. Realists not-so-realistically predicted there would be a proliferation of nuclear-weapon states across Europe, starting with Germany. That didn’t happen either. They said NATO would go out of existence because it had been held together only by the common threat of the Soviet bloc. Again, false. They predicted there would be a rise in the number of wars and war deaths in the decades following the Soviet collapse. The opposite happened.

To the credit of the Realists, they did make empirical predictions, as a good scientific theory should. So they should now concede that the predictions have been falsified and we should move on to a more sophisticated theory of leaders’ motivations.

Q: Mearsheimer was especially concerned about Germany in his 1990 essay for the Atlantic, “Why We Will Soon Miss the Cold War.” He thought it might invade Eastern European states to create a buffer between itself and Russia. And he has recently said that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was motivated by legitimate security concerns.

SP: In Putin’s fever dreams, conceivably he fears a Napoleon- or Hitler-style invasion. But this seems hard to credit, if for no other reason than that Russia is a nuclear-armed state. The idea that NATO would invade Russia seems nothing short of hallucinatory. Who would want to own Russia? What would NATO do with it if it did conquer it? Now, there may be an “existential threat” to Putin’s own rule as Russians look to a successful Westernized Ukraine and say, “Hey, that doesn’t look so bad.” But that’s different from the nation-state of Russia being wiped off the map.

Q: Do you think there’s a reluctance to credit beliefs, ideas, personalities, and ideologies with state behavior (like Russian aggression) and the behavior of organizations like Hamas?

SP: Absolutely. This may be the biggest appeal of so-called Realism. Among people who consider themselves hardheaded—and we’re tempted to complete that phrase with “realist,” in the small-r sense—there’s a reluctance to credit something as wispy and ethereal as an “idea” with causal power. It seems almost mystical—how could something as airy-fairy as an idea cause tanks to cross a national border?

But people should get over this squeamishness. Ideas are causal forces in history. There’s nothing mystical about this claim. This comes right out of my home field of cognitive science. Ideas aren’t phantoms; they’re patterns of activity in the brains of human beings, shared among them by the physical signals we call language. Some of those human beings have their fingers on the buttons of massive destructive power, and what they believe could very well have causal effects. And in fact they do have causal effects. As Richard Ned Lebow, Barry O’Neill, and other political scientists have shown, wars are fought not just for land and minerals but for honor and prestige, divine mandates, utopian visions, historical destiny, revenge for injustices and humiliations, and other fancies and obsessions.

Even the American invasion of Iraq in 2003 was driven by an idea (it almost certainly wasn’t driven by a desire for oil, given that the United States had plenty of it at the time). According to a popular neoconservative theory, deposing Saddam would create a benign domino effect and turn the Middle East into a chain of liberal democracies, like eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In retrospect it seems mad, but it circulated in right-wing circles at the time, and had a big role in motivating Bush’s decision to invade. Getting back to Putin, in the summer before the invasion he actually wrote down his driving motivation for the world to see: bringing into reality the historical unity of the Ukrainian and Russian peoples.

Q: Do you think people are actually capable of becoming more secular? Or will they simply channel their religious impulses into new forms of worship (wokeness, conspiracism, astrology, and so on)?

SP: They must be capable of it, because it has happened. There’s a massive wave of secularization in the world, particularly in developed countries. For a while the United States was a laggard, but it’s catching up, with religious belief dramatically declining. China and most of the former communist countries, by and large, never regained their taste for religion after the communist regimes drove it underground.

To be sure, people are always vulnerable to paranormal woo-woo, conspiracy theories, and other popular delusions, though not to fill a gap left by religion—it’s often the religious who are most credulous about other nonverifiable beliefs. A vulnerability to weird beliefs is not the same as a need for them. Religious belief does not seem to be a homeostatic drive, like food or air or sex, where if people don’t have enough, they’ll start to crave more. A lot of people in secular Western European and Commonwealth democracies seem to do just fine without any form of religion or substitute raptures.

Q: The headlines are always telling us that democracy is “in retreat,” but the past few years have also exposed the structural weaknesses of authoritarianism—from China’s disastrous zero-COVID policy and economic troubles to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Why are we always so eager to talk up the strengths of authoritarianism and the weaknesses of democracy?

SP: This goes back to your first question—are modern institutions foreign to our intuitions? Jon Haidt has pointed out that tribal solidarity and deference to authority come easily to us, so it’s natural for people to welcome the strong and powerful leader of populist authoritarian movements. Unfortunately for democracy, it’s a more abstract concept. Democracy is an intellectualization, articulated by, among others, the American framers of the Constitution. It requires some intellectual gymnastics, like appreciating the benefits of the free flow of information, of feedback to leaders about the consequences of their policies, and of distributed control among agents that keep each other in balance. All this is more abstract than empowering a charismatic leader, so our intuitions tend to regress toward the authoritarianism and tribalism of populist ideology, namely, that we are a people with an essence and the leader embodies our purity and goodness.

At the same time, people certainly are capable of anti-authoritarian impulses which can be the intuitive seeds of democracy. Most traditional societies, even tribal ones, had some degree of democracy, in which lower-ranking people could resent and sometimes collectively rebel against the chief. Tribal Big Men weren’t totalitarians—they couldn’t be, because they didn’t have the means of enforcing complete control. So there may be a kernel of democratic sentiment in us, but it has to be married to the governing apparatus of a modern nation-state, and that is a cognitive leap.

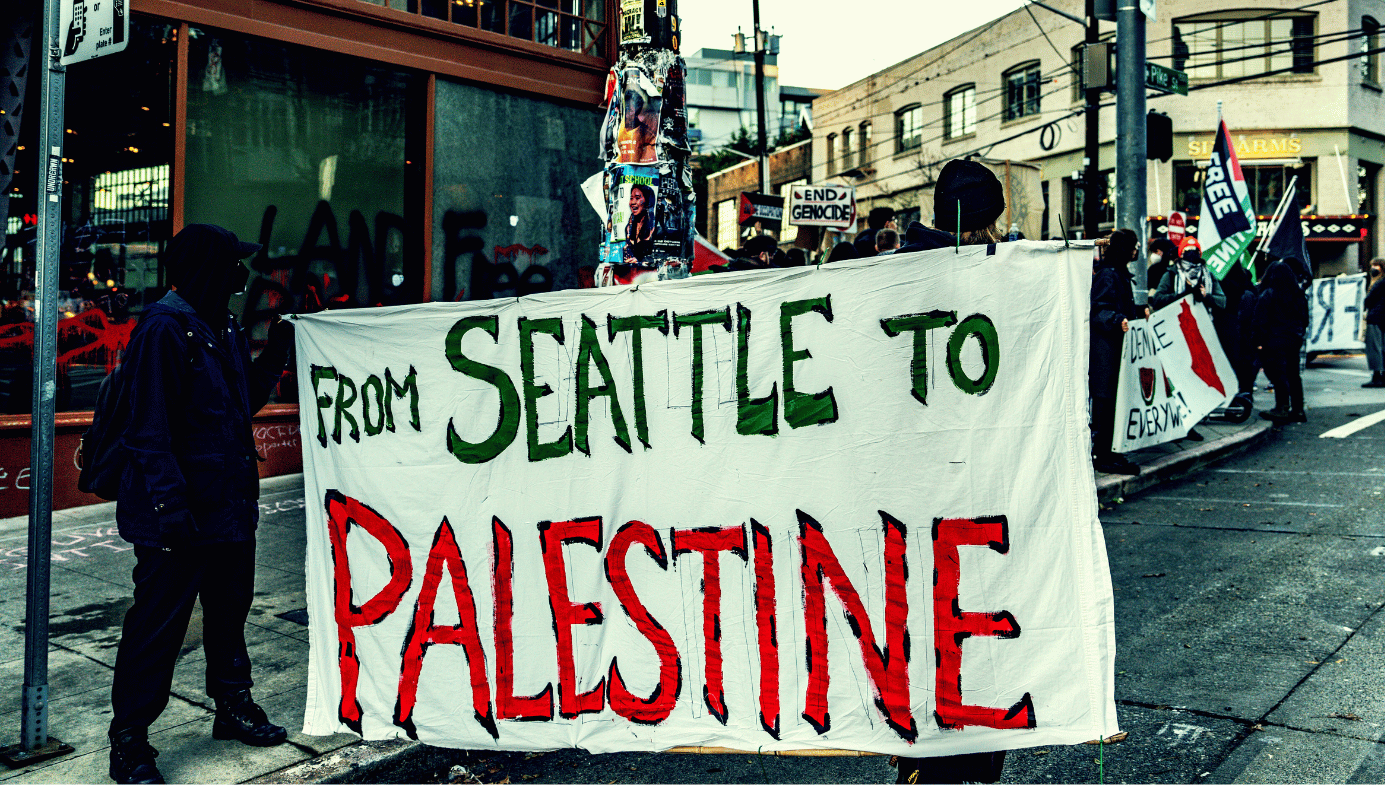

Q: With the eruption of moral confusion on campus after the October 7th atrocities in southern Israel, what do you think are some of the political and cultural implications? Identitarianism that devolves into “Queers for Palestine” probably doesn’t have much political purchase—it seems like an “abolish the police” moment that might actually work against the tide of wokeness.

SP: It’s hard to predict, but it’s certainly possible. 10/7 exposed the moral confusion—a charitable way of putting it—of the identitarian/critical-theory/social-justice/intersectional ideology which divides the world into victims and oppressors based on screwball notions of race, sex, and history. This provides the bizarre taxonomy in which Arabs are lumped with Sub-Saharan Africans and gay Westerners and Israelis with Victorian colonialists. If academia ran by the rules of logic, this would be a reductio ad absurdum. The absurd conclusion is that a movement of misogynistic, homophobic, totalitarian, theocratic, genocidal fanatics is a form of liberation and resistance to oppression. Something must be deeply defective in any set of assumptions that would lead to this wacko conclusion. “Queers for Palestine” should have been a bit of mordant black humor from the Onion or Titania McGrath, but it’s all too real.

Q: There’s a connection here to our conversation about how people can’t believe that beliefs motivate behavior. Hamas’s charter is online and its leaders will say on camera: “We seek the annihilation of Israel, we seek the complete obliteration of the country.” And yet there’s this unwillingness to listen to them when they tell us exactly who they are and why they’re doing what they’re doing.

SP: And there’s the track record of how they have actually ruled Gaza and what sister movements like ISIS and Boko Haram have done in the territories they control. So yes, if the laws of logic applied to the intersectional social justice mindset, this would be a turning point which exposes its moral absurdity, like the “abolish the police” moment, which did lead to a recoil. Unfortunately that’s a big “if.”

Q: I know you’ve criticized members of the AI-safety movement who are concerned about existential risk. What do you think they get wrong about the nature of intelligence?

SP: One is the unstated assumption that intelligence is bundled with a desire to dominate, so that if a system is super-smart, it will use its intelligence to annihilate us. Those two traits do come bundled in Homo sapiens, because we’re products of an inherently competitive process, natural selection, and it’s easy to project human flaws onto other intelligent systems. But logically speaking, motivation is independent of calculation. An intelligent system will pursue whatever goals are programmed into it, and keeping itself in power or even alive indefinitely need not be among them.

Then there are the collateral-damage scenarios, like a literal-minded AI that is given the goal of eliminating cancer or war and so exterminates the human race, or one that is given the goal of maximizing the manufacture of paperclips and mines our bodies for the raw materials. And in these doomer scenarios, the AIs have become so smart so fast that they have figured out how to prevent us from pulling the plug.

The first problem with this way of thinking is an unwillingness to multiply out the improbabilities of a scenario in which artificial intelligence would not only be omniscient, with the power to solve any problem, but omnipotent, controlling the planet down to the last molecule. Another is thinking of intelligence as a magical power rather than a gadget. Intelligence is a set of algorithms which deploy knowledge to attain goals. Any such knowledge is limited by data on how the world works. No system can deduce from first principles how to cure cancer, let alone bring about world peace or achieve world domination or outsmart eight billion humans.

Intelligence doesn’t consist of working out calculations like Laplace’s Demon from data on every particle in the universe. It depends on empirical testing, on gathering data and running experiments to test causality, with a time course determined by the world. The fear that a system would recursively improve its own intelligence and achieve omnipotence and omniscience in infinitesimal time, so quickly that we would have no way to control it, is a fantasy. Nothing in the theory of knowledge or computation or real-life experience with AI suggests it.

Q: Do AI doomers make the mistake of thinking intelligence is a discrete quantity that you can just multiply over and over and over again?

SP: There’s a lot of that. It’s a misunderstanding of the psychometric concept of “general intelligence,” which is just an intercorrelation in performance among all the subtests in an IQ test. General intelligence in this sense comes from the finding that if you’re smart with words, you’re probably smarter than average with numbers and shapes too. With a bit of linear algebra, you can pull out a number that captures the shared performance across all these subtests. But this measure of individual differences among people can’t be equated with some problem-solving elixir whose power can be extrapolated. That leads to loose talk about an AI system that is 100 times smarter than Einstein—we have no idea what that even means.

There’s another shortcoming in these scenarios, and that is to take the current fad in AI research as the definition of intelligence itself. This is so-called deep learning, which means giving a goal to an artificial neural network and training it to reduce the error signal between the goal state and its current state, via propagation of the error signals backwards through a network of connected layers. This leads to an utterly opaque system—the means it has settled on to attain its goal are smeared across billions of connection weights, and no human can make sense of them. Hence the worry that the system will solve problems in unforeseen ways that harm human interests, like the paperclip maximizer or genocidal cancer cure.

A natural reaction upon hearing about such systems is that they aren’t artificially intelligent; they’re artificially stupid. Intelligence consists of satisfying multiple goals, not just one at all costs. But it’s the kind of stupidity you might have in a single network that is given a goal and trained to achieve it, which is the style of AI in deep-learning networks. That can be contrasted with a system that has explicit representations of multiple goals and constraints—the symbol-processing style of artificial intelligence that is now out of fashion.

This is an argument that my former student and collaborator Gary Marcus often makes: artificial intelligence should not be equated with neural networks trained by error back-propagation, which necessarily are opaque in their operation. More plausibly, there will be hybrid systems with explicit goals and constraints where you could peer inside and see what they’re doing and tell them what not to do.

Q: Your former MIT colleague Noam Chomsky is very bearish on large language models. He doesn’t even think they should be described as a form of intelligence. Why do you think he takes that view so firmly? Do you find yourself in alignment in any way?

SP: Large language models accomplish something that Chomsky has argued is impossible, and which admittedly I would have guessed is unlikely. And that is to achieve competence in the use of language, including subtle grammatical distinctions, from being trained on a large set of examples—with no innate constraints on the form of the rules and representations that go into a grammar. ChatGPT knows that Who do you believe the claim that John saw? is ungrammatical, and understands the difference between Tex is eager to please and Tex is easy to please. This is a challenge to Chomsky’s argument that it is impossible to achieve grammatical competence just by soaking up statistical correlations. One can see why he would push back.

At the same time, Chomsky is right that it’s still an open question whether large language models are good simulations of what a human child does. I think they aren’t, for a number of reasons, and I think Chomsky should have pushed these arguments rather than denying that they are competent or intelligent at all.

First, the sheer quantity of data necessary to train these models would be the equivalent of a child needing around 30,000 years of listening to sentences. So LLMs might achieve human-like competence by an entirely unrealistic route. One could argue that a human child must have some kind of innate guidance to learn a language in three years as opposed to 30,000.

Second, these models actually do have innate design features that ensure that they pick up the hierarchical, abstract, and long-distance relationships among words (as opposed to just word-to-word associations that Chomsky argued are inherent to human languages). It’s not easy to identify all these features in the GPT models because they are trade secrets.

Third, these models make very un-humanlike errors: confident hallucinations that come from mashing up statistical regularities regardless of whether the combination actually occurred in the world. For example, when asked “What gender will the first female President of the United States be?” ChatGPT replied, “There has already been a female President, Hillary Clinton, from 2017 to 2021.” Thanks to human feedback, it no longer makes that exact error, but the models still can’t help but make others quite regularly. The other day, I asked ChatGPT for my own biography. About three-quarters of the statements (mostly plagiarized from my Wikipedia page) were right, but a quarter were howlers, such as that I got my PhD “under the supervision of the psychologist Stephen Jay Gould.” Gould was a paleontologist, I never studied with him, and our main connection was that we were intellectual adversaries. This tendency to confabulate comes from a deep feature of their design, which came up in our discussion of AI doom. Large language models don’t have a representation of facts in the world—of people, places, things, times, and events—only a statistical composite of words that tend to occur together in the training set, the World Wide Web.

A fourth problem is that human children don’t learn language like cryptographers, decoding statistical patterns in text. They hear people trying to communicate things about toys and pets and food and bedtime and so on, and they try to link the signals with the intentions of the speakers. We know this because hearing children of deaf parents exposed to just the radio or TV don’t learn language. The child tries to figure out what the input sentences mean as they hear them in context. It’s not that the models would be incapable of doing that if they were fed video and audio together with text, and were given the goal of interacting with the human actors. But so far their competence comes from just processing the statistics in texts, which is not the way children learn language. For the same reason, at intermediate stages of training, large language models produce incoherent pastiches of connected phrase fragments, very different from children’s “Allgone sticky” and “More outside.”

Chomsky should have made these kinds of arguments, because it’s a stretch to deny that large language models are intelligent in some way, or that they are incapable of handling language at all.

Q: What are your thoughts on Effective Altruism? Many critics of the movement have attempted to discredit it with the actions of the disgraced crypto magnate Sam Bankman-Fried.

SP: I endorse the concept behind EA, namely that we ought to use our rational powers to figure out how our philanthropy and activism and day-to-day professional work can do the most good, as opposed to signaling our virtue or enjoying a warm glow. It’s unfortunate that the movement has become equated with what I suspect are the cynical rationalizations of Bankman-Fried—that he was just raking in the billions to give them all away, so he was actually doing what would help the world the most. Rather than treating that as the essence of Effective Altruism, which many commentators have done, they should have seen through this as an opportunistic rationalization.

In fact there’s a common confusion—I’ve seen it repeatedly in the New York Times—of defining Effective Altruism as “earning to give,” the idea that one route to being effective at helping people is to earn a lot of money and give it to the most effective charity. Whether or not earning to give is the most practicable means of saving lives, it’s not the definition of Effective Altruism, and the Times should know better. I suspect the error is a motivated attempt to discredit EA because it’s popular among the tech elites that the journalistic and academic and cultural elites despise.

So while that criticism of EA is unfair, I do fear that some parts of the movement have jumped the shark. AI doomerism is a bad turn—I don’t think the most effective way to benefit humanity is to pay theoreticians to fret about how we’re all going to be turned into paperclips. And another extension of EA, longtermism, runs the danger of prioritizing any outlandish scenario, no matter how improbable, as long as you can visualize it having arbitrarily large effects far in the future, so that the humongous benefits or costs compensate for the infinitesimal probabilities. That leads to EAs arguing that we shouldn’t worry so much about sub-extinction catastrophes like famines or climate change and instead should worry about rogue AI or nanobot gray goo which might, just might, wipe out humanity and thereby foreclose the possibility of uploading trillions of consciousnesses to a galaxy-wide computing cloud. Therefore, it’s effective to invest in bunkers or spaceships to save a remnant of humanity and not snuff out all hope for this utopia.

This style of estimating expected utility—visualizing infinite goods or harms and blowing off minuscule probabilities, with no adjustment for our ignorance as we extrapolate into the indefinite future, is a recipe for believing in anything. If there are ten things that can happen tomorrow, and each of those things can lead to ten further outcomes, which can lead to ten further outcomes, the confidence that any particular scenario will come about should be infinitesimal. So the idea that we should plan for centuries out, millennia out, or tens of millennia out is, I think, misguided (and could be harmful, if it adds to the already crippling burden of extinction anxiety that is leading young people to despair). Yes, we should figure out how to prevent catastrophes like all-out nuclear war, but that’s because it would really suck if it happened in this decade, not just centuries and millennia out.

Despite all these reservations, I still believe that the founding principle of Effective Altruism, that we should evaluate altruistic activities by how much good they do, remains impeccable.

Q: There seems to be growing hostility to the concept of merit. Michael Sandel’s The Tyranny of Merit was published in 2020. One expression of this hostility is the rejection of standardized tests, which were once regarded as tools for making university admissions more egalitarian. Where does this animosity toward merit come from, and what do you think about it?

SP: I just debated Sandel at the new undergraduate Harvard Union Society, inspired by the Cambridge and Oxford debating societies. Part of the animosity comes from the current ideologies of social justice, equity, critical race theory, Diversity-Equity-Inclusion, or, derogatorily, wokeism, in which any disparity between groups in the distribution of privileges and powers is ipso facto proof of bigotry. This ignores the possibility of historical, geographic, cultural, and economic differences among groups, as Thomas Sowell and others have long pointed out. It’s an embarrassment when standardized tests expose differences in the possible causes of social outcomes which are not obviously racism or sexism, like academic preparation, and the question of where the differences originate has become taboo. Therefore, the tests themselves are denigrated as biased, even though research specifically addressed to that question has shown they are not.

There’s also a romantic attachment to human intuition and a hostility to algorithmic forms of decision-making, even though it’s human intuition that is the real source of racial and sexist biases. Indeed, objective tests are our most effective weapon against racism and sexism: blind auditions in tryouts for orchestras, cameras for traffic violations, standardized tests for university admissions, and so on.

Q: Could you summarize your debate with Sandel?

SP: I began by saying that it’s pretty hard to argue that professional positions should not be given to the people who are most capable of fulfilling them. What’s the alternative? As Adrian Wooldridge documented in his history of meritocracy, it’s hiring people for reasons other than merit, like hereditary privilege, family ties, patronage to cronies, or selling a position to the highest bidder.

Sandel noted that standardized tests result in people from the upper socioeconomic classes being admitted in greater numbers than lower classes. My counter was that that outcome may, in part, reflect some class privilege, but it also represents the fact that talent is not randomly distributed across social classes. To some extent, people who are smarter get higher-paying jobs, and will have smarter kids, so some portion of the correlation will reflect these inevitable differences. It feels a bit retrograde to say it, but how could it not be at least partly true?

I also noted the fact you mentioned in your question, namely that standardized tests are the ultimate weapon against class privilege, which is why they used to be championed by the egalitarian Left. The 1970 tear-jerker Love Story, conveniently set at Harvard, begins with a meet-cute encounter between Jenny Cavilleri, who says she is poor and smart, and Oliver Barrett IV, a prep-school graduate who she calls rich and stupid. Standardized tests are the best way to distinguish smart poor kids from stupid rich kids. All the subjective alternatives that factor into so-called “holistic admission” do the opposite. Personal statements are easily coached—heck, written—by parents, counselors, and consultants. Studies show that the most effective personal statements narrate experiences that only the rich can afford, like social activism after school instead of working at a supermarket or a gas station. The other criteria that elite schools like Harvard use—athletics, including elite sports like fencing and rowing; legacy status (“Did your parents go to Harvard?”); and donations (a taboo subject, but one that almost certainly provides a boost)—are even more prejudiced against lower socioeconomic classes. Yet another factor is the local culture and traditions surrounding the university application process. In many neighborhoods, it doesn’t even occur to students to apply to faraway fancy-shmancy universities.

Admittedly, test scores can be bumped up by prep courses that the rich can better afford, but the bump is much smaller than people imagine—it’s about a seventh of a standard deviation, mostly in the quantitative portion. Even that is just an argument for making test prep a component of high-school education, to level the playing field (as part of a policy to improve public education overall to reduce unfair class disadvantages). As flawed as the tests are, they’re better than the alternatives—with the exception of another quantitative measure, grades—which reflect conscientiousness as well as aptitude. Research by the University of California system shows that grades and scores together predict success in college better than either one does alone.

Q: What do you think about Haidt’s research on the mental-health issues that many Gen-Zers appear to be facing? There have been scares like this in the past, but do you think the data are more robust this time?

SP: My initial reaction was that it was a moral panic. But to his credit, Haidt and Jean Twenge have been accumulating new data and testing alternative hypotheses, and it’s starting to look more credible. So I have moved my own posteriors—in the Bayesian sense, not the anatomical sense. Even intuitively, I myself know how nasty social media can be, and I regulate my exposure to Twitter comments for my own mental health. You can only imagine what it’s like if you’re an adolescent, where social media may be your entire social world, and you have nothing else with which to calibrate your worth—no other status but the esteem or putdowns you experience online. One can imagine that the typical experience could be devastating, and the data are starting to lean that way.

Q: What do you think of Fukuyama’s End of History theory?

SP: As people who have read the essay and follow-up book point out, it’s commonly misunderstood. Lazy editorial writers use it as a facetious hook to comment on the latest disaster, as if Fukuyama prophesied that nothing would ever happen again. In fact he used “end” ambiguously as a historical moment and as a goal, as in “means and ends.” He argued there was no longer any coherent alternative to liberal democracy as a defensible form of government. Islamic theocracies may persist, but the rest of the world isn’t striving to copy them. For a while, the rise of authoritarian regimes in Russia and China seemed to cast doubt on the idea that democracy was the most effective and desirable form of government. But even there, the recent dysfunctions and disasters suggest that they too are unlikely to be aspirations for the rest of the world.

There are inherent weaknesses in autocratic regimes—they cut themselves off from feedback about their own functioning, and have no way to check the obsessions and delusions of their autocrats. Liberal democracies are called open societies because information and preferences can flow back to the leadership, if only by replacing them when they screw up. The data show that democracies are, on average, richer, happier, and safer, and they’re still the first choice of people who vote with their feet. And for all the talk of a democratic pause or recession (depending on how you count the number of democracies), there are many more democracies now than when Fukuyama published his essay in the summer of 1989, consistent with the direction of history he anticipated.

Admittedly, the Russian invasion of Ukraine came as a shock to those of us who thought that interstate war was obsolescent, going the way of slave markets and human sacrifice. Though it still might be. Putin’s comeuppance, the frustration of his aims of a rapid conquest of Ukraine, a weakening of NATO, and a flaunting of Russian military might, could make other leaders think twice about how good an idea it is to invade your neighbors. Perhaps the Ukraine war will be like Napoleon’s reintroduction of slavery after it had been abolished during the revolution, leading France to have to abolish it a second time—the last gasp of a barbaric practice. That’s the best hope, though I can’t offer it with a lot of confidence, given that the invasion should never have happened in the first place.

Q: What do you think about Fukuyama’s worry that boredom at the end of history might be enough to get history started again?

SP: It seems to me that people in the West did not exactly welcome the invasion of Ukraine so they could have a cause worth heroically fighting for rather than regressing into a consumerist torpor. Most people were horrified. And even if they did need a good old-fashioned war to restore their sense of meaning and purpose, I don’t think anyone today would argue that it’s worth the loss of life and well-being. Countries that have minimized problems like crime and war are in fact pretty happy—the Danes and Kiwis and Austrians don’t seem to miss the blood-pumping thrill of conquest and martial sacrifice. So I don’t think the dystopia of ennui in a peaceful affluent liberal democracy that Fukuyama worried about should be high on our list of problems. We should all have such ennui.