Politics

The New Normal?

Election results in the Netherlands and Argentina provide evidence of the vigour and variety of the New Right and its global reach.

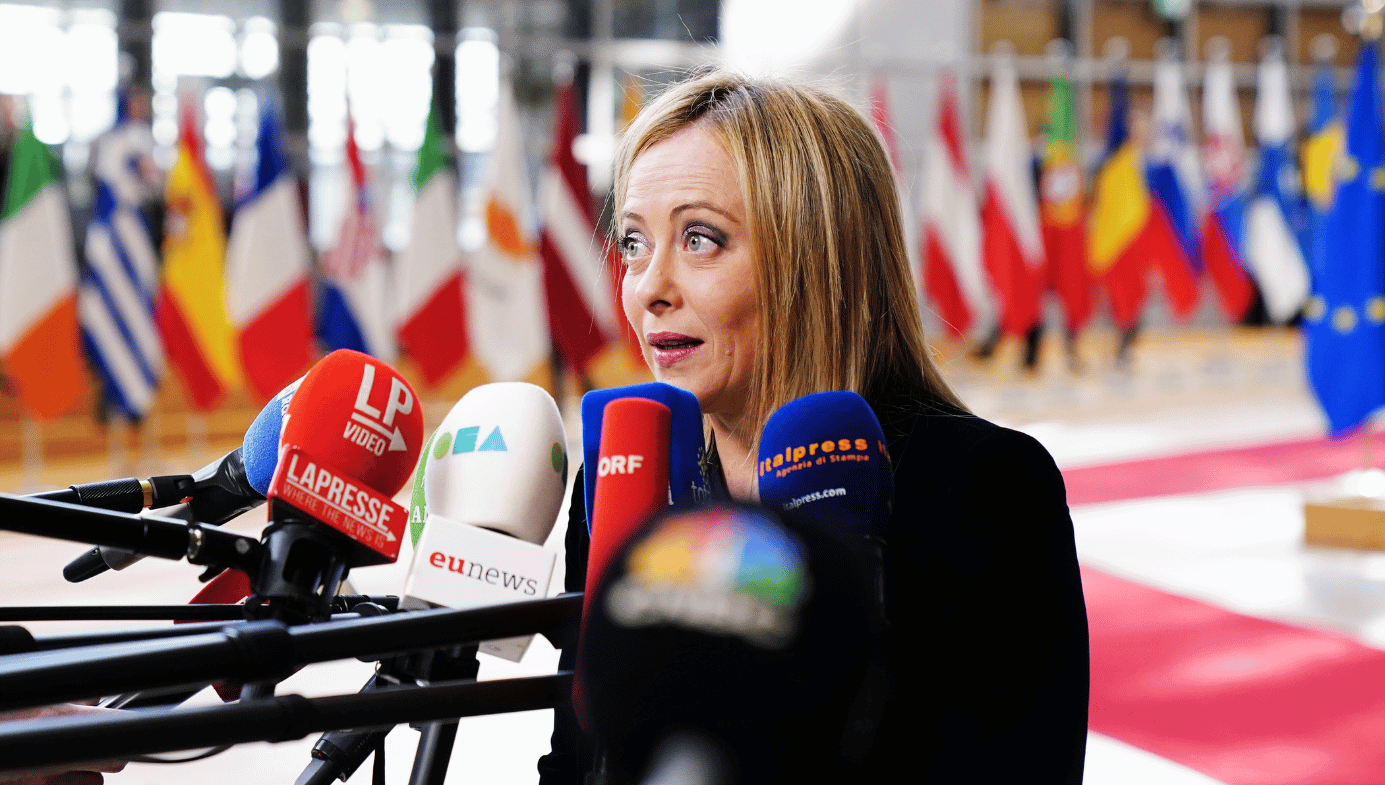

The New Right comes in two by two. In September last year, elections in Sweden and Italy delivered New Right parties into power. Jimmy Akesson’s Sweden Democrats became very influential on the centre-Right-led governing coalition in Stockholm, and Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia were placed unambiguously in charge in Rome. Two European nations less alike you’d be hard-pressed to find. Yet the triumphant parties believe in most of the same things—sharply reduced immigration, increased birth rates, Euroscepticism, distrust of globalisation and Islam, strong families, and support of the Christian faith.

Earlier this week, another sharply diverse pair joined the steadily growing ranks of the New Right. In the Netherlands, the Freedom Party (Partij voor de Vrijheid) led for the past quarter-century by Geert Wilders, won 37 seats, thereby doubling its pre-election total and placing it 12 seats ahead of Labour and the Green Left. Nearly 7,500 miles to the south-west and four hours behind, Javier Milei, an economist and popular talk-show host, won the presidency in Argentina by a considerable margin.

There are at least as many differences between these parties and individuals as there are similarities—in their national contexts, histories, and party cultures. But the fundamental lesson these results impart is that the New Right parties are increasingly—if often reluctantly and controversially—accepted. The cordons sanitaires erected around them when they first emerged was designed to keep them in the political and (more importantly) moral wilderness until their support collapsed. That strategy has not worked, leaving Germany’s Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) as the only untouchable major party.

Yet even the AfD’s pariah status is waning. The German centre-Right will be forced to concede that there is no alternative to an alliance with the party once it scores over 20 percent in the opinion polls. Wilders has also been saddled with pariah status during his decades in opposition (albeit less definitively than in Germany, where Thomas Haldenweg, head of the country’s domestic intelligence agency, called on Germans to boycott the AfD). The other main Dutch parties are now hedging their bets, either remaining silent about coalition possibilities, or saying they would accept Wilders’s support, but not as a prime minister.

Most of the centre-Left and centre-Right parties in Europe are struggling, though some more than others. On the Left, only in Britain does a major social-democratic party—the Labour Party—seem to be poised for office. In France, Sweden, Italy and Greece, centrist parties are much weakened. This is also true in Germany, where the Social Democrats presently lead the governing coalition. In Denmark, the Social Democrats are still in power, but only achieved a win last year by legislating for the toughest anti-immigrant regime in Europe, a move that turned out to be popular.

The most obvious conclusion to be drawn from all this is that European publics dislike tens of thousands of immigrants arriving in their states at a rate of hundreds per day. A recent column by populist blogger Matthew Goodwin forecasts that our “ongoing and visibly failing experiment with mass immigration has placed a ticking time-bomb at the heart of our politics … the status-quo, for millions of ordinary people out there in the country, is completely unsustainable.” He believes that “a shared sense of national identity, culture, values, and ways of life—are now being readily sacrificed by a new ruling class which either struggles to relate to these things or simply does not care about them.”

Goodwin maintains that a “new ruling class” composed of centre-Left and centre-Right politicians, senior civil servants, most of the media and creative industries, the highly educated, and the churches now dominates much of national life. They care little for their country and impose their liberal views on the lower classes while being largely exempt from the problems high immigration brings. This view is now a staple of New Right politics and aims to solidify these parties’ status as the authentic representatives of the working class. In an impromptu speech, Wilders told a gathering of his supporters that “the Dutchman will get his country back.”

The New Right is no longer willing to be the reluctant partners of centre-Right parties hoping to use them to form governments. They are making a strong claim to become a new normal. “The people of Western Europe,” writes Ralph Schoellhammer in UnHerd, “are losing their hesitancy when it comes to voting for right-wing parties, and Wilder’s success is most likely only the beginning.” In a similar vein, Ross Douthat, a conservative columnist at the New York Times, invited his readers to “imagine a future in which this order stabilizes and normalizes somewhat and people stop talking about an earthquake every time a populist wins power, or democracy being saved every time an establishment party wins an election.” (That future may be some time off, especially for most readers of the New York Times.)

Douthat had the new president of Argentina in mind when he wrote that. It’s an observation more easily made of a country like Argentina, where (unlike European and North American democracies, for all their many problems) the economy really is in a dire state. An inflation level of nearly 145 percent means prices rise at least once a week; a 40 percent poverty rate means hunger for many, and stunted growth for their children.

Milei is someone whose erratic behaviour and promises—wielding a chainsaw to dramatise the swingeing cuts he hopes to make to various ministries and the Central Bank, a vow to immediately introduce the US dollar as the country’s currency, calling Pope Francis “a filthy leftist” and climate change “a socialist hoax”—are more comic operatic than political. Aware of all this, the country has plainly decided that nothing could possibly be worse than the succession of Peronist rulers who have driven the country into a cul-de-sac. “I have been waiting for this all of my life,” enthused a Buenos Aries psychotherapist as he banged a drum in the street. “No more Peronists, no more thieving, no more lies. My children will get to live in a free country.”

🇦🇷 JAVIER MILEI, NUEVO PRESIDENTE DE LA ARGENTINA

— antiprogre.com (@antiprogrecom) November 19, 2023

HA ARRASADO EN LAS ELECCIONES#Elecciones2023 #EleccionesArgentina #EleccionesArgentina2023 #Ballotage2023 #Ballottage2023 pic.twitter.com/2coKzpd45s

Though Meloni and Trump both sent their congratulations welcoming Milei into the broadening church of the New Right, he is less classifiable than either. Nor is he a close copy of Jair Bolsonaro, the former President of neighbouring Brazil. Bolsonaro struggled to understand economic issues, while Milei, although unconventional, is well-trained and well-read in market economics. And, at least before the prison gates of governance close about him, he has said that he is keen to privatise as much of the Argentinian economy as possible.

There is no shortage of astute commentary pointing to the immensity of Milei’s task. His party has only a handful of MPs in the parliament and none of the powerful state governorships. The central bank has almost no dollar holdings and cannot borrow. His own positions are difficult to categorise—a strongly pro-capitalist anarcho-libertarianism mixed with social conservatism (he is against abortion). As the Spanish journalist Federico Molina writes, he “throws ideas around like grenades, waiting for them to go off.”

In the Netherlands, the 60-year-old Wilders will likely soon begin to negotiate his way through the country’s ultra-fragmented politics in the hope of securing a premiership he must have thought would never be his. In Argentina, the 53-year-old Milei has jumped every conventional political fence to try and mend a broken economy. Neither result seemed likely; but their separate victories provide evidence of the vigour, variety, and global reach of the New Right.