Art and Culture

Concealed Carry

For more than five centuries, the humble pocket has changed the way we equip ourselves to face the world.

Like printed books, perspective drawing, and double-entry bookkeeping, pockets were heralds of the modern era. In most times and places, people have either carried their money, combs, papers, and other small items in bags separate from their garments or tucked them into belts or sleeves. Integrated pockets are a product of European tailoring, which dates back only to the 14th century. They emerged when men’s breeches ballooned in the mid-1500s.

Early pockets were bags sewn to the inside of the waistband and otherwise hanging loose. They were significantly larger than modern pockets—a rare surviving example from 1567 is a foot deep—and sometimes included drawstrings. Regardless of size, the critical change was that the pocket became part of the clothing and thus a more secure and intimate extension of the wearer. “Yoking bag to breeches in what looks like an improvisational ‘lash-up’ created a tool demonstrably more private and personal than the public-facing purse,” writes Hannah Carlson in her newly published Algonquin Books release, Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close.

To tell the story of pockets, Carlson, a dress historian at the Rhode Island School of Design, mines literature and art, including once-popular works that have lapsed into obscurity. She reads old newspapers, magazines, and advice books. She scours descriptions of runaway indentured or enslaved workers. She examines historical garments. Organized in thematic chapters across a loosely chronological arc, Pockets readably presents the results of Carlson’s impressive research, demonstrating the many ways in which material culture can illuminate social, economic, and political history.

Pockets changed the nature of clothes, allowing them to encompass hidden tools and meaningful treasures. “Once the wearer places something inside their pocket,” Carlson notes, “that thing disappears, enfolded and seemingly absorbed into uncertain depths.” If that thing is a handgun, the pocket’s combination of convenience and secrecy poses a threat. Western gun control was a response to pocket pistols.

Invented around the same time as the pocket, the wheel-lock pistol could be loaded in advance, and was small enough to be secreted in a pocket, leading to its slang term “pocket dag.” In 1549, an intruder broke into Edward VI’s apartments. When the eleven-year-old king’s dog started barking, the intruder—an ambitious and notorious rake named Thomas Seymour—pulled a pistol out of his pocket and shot it. The monarch promptly banned anyone within three miles of his residence from carrying a pocket pistol. In 1584, a Spanish sympathizer used one to kill Prince William (the Silent) of Orange, the leader of the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule. It is recorded as the first political assassination by handgun.

Once the layered ensemble of knee-length coat, vest, and breeches introduced in the seventeenth century made multiple pockets practical and easily accessible, they quickly proliferated. By 1726, Jonathan Swift portrayed the Lilliputians in Gulliver’s Travels discovering ten pockets in the clothing of the “man mountain”: two each in Gulliver’s coat and waistcoat and six in his breeches. Their contents include a handkerchief, a snuff box, a leather-bound journal, a comb, two pistols, silver and copper coins, a razor, a knife, a watch on a chain, and a net purse holding gold coins. Gulliver also records that he had an undetected “secret pocket,” containing spectacles, a pocket telescope, and “some other little conveniences.”

Pockets, Carlson suggests, encouraged craftsmen to “miniaturize useful instruments,” such as knives and sextants, “with the notion of portability in mind.” In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759, Adam Smith suggested the opposite causality. He singled out the era’s popular small gadgets, which included watches, nutmeg grinders, and “tweezer cases,” or etuis, as “trinkets of frivolous utility” whose usefulness was less important than their ingenuity. Their owners, he wrote, “contrive new pockets, unknown in the clothes of other people, in order to carry a greater number.”

For all the appeal of pocket gadgets, however, the most frequent contents of pockets may well be the owner’s hands. Carlson devotes an enjoyable chapter to the centuries-long debates over the propriety of sticking one’s hands in one’s pockets. “Anxious mothers and schoolmasters,” she reports, “stitched boys’ trouser pockets closed to prevent them from ‘the trick of putting their hands into them’ through the end of the nineteenth century.” Depending on posture and circumstances, the gesture could be sexually provocative or fashionably nonchalant, menacing or friendly.

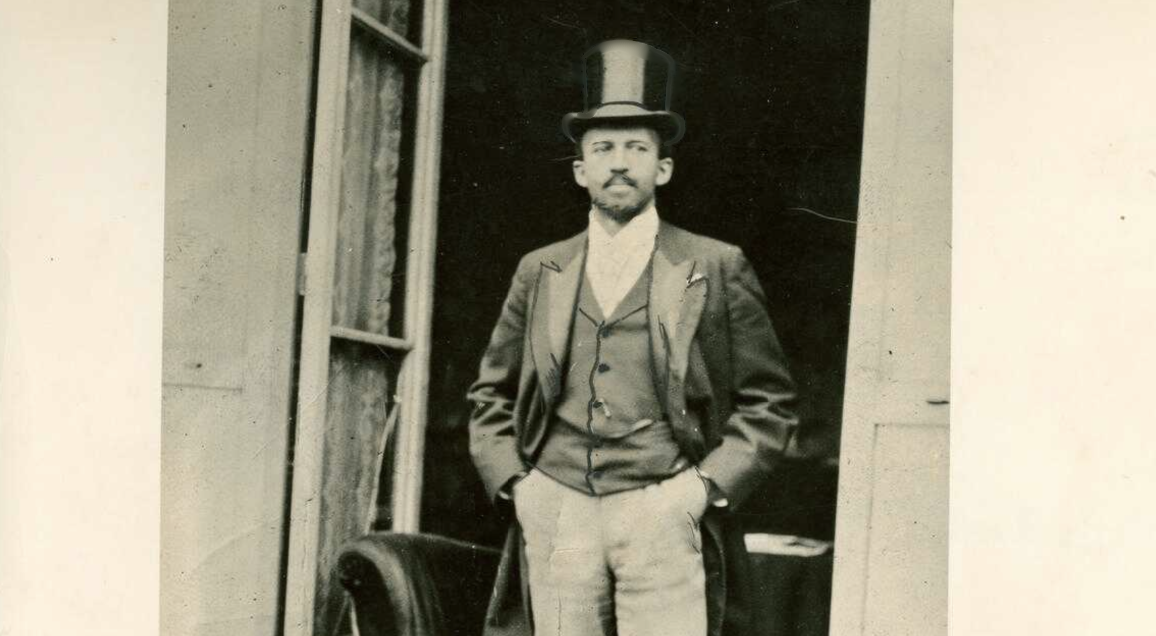

Carlson presents contrasting portraits of Walt Whitman, dressed in a loose open shirt and canvas trousers, and W.E.B. Du Bois wearing a top hat, starched collar, waistcoat, and frock coat. Whitman’s clothes are timeless work garb, Du Bois’s the height of 1900 fashion. With his right hand propped at his waist, Whitman has left hand in his pocket. Du Bois puts both hands in his pockets, sweeping his coat behind him. In each case, the resulting pose is self-assured, arresting, and quintessentially American.

It’s also implicitly masculine. Du Bois’s pose mirrors another proud image in the book—an 1860 magazine illustration titled A Boy’s First Trousers. Pockets and their contents defined boys as explorers, collectors, and tool wielders—as “real boys” and future men.

“Our fondness for pockets calls for a revision of what it means to be dressed, to acknowledge that we’ve achieved our sense of self-sufficiency with an array of concealed compartments,” Carlson writes. Pockets foster a sense of personal independence, allowing the owner to march into the world unencumbered yet prepared. So, Carlson argues, the common absence of pockets in women’s garments rankles.

Women used to have their own pockets, tied around the waist and layered where needed—outside the skirt when taking money at a market, above the petticoat for ordinary use. Like men’s original sewn-in pockets, tie-on pockets were long and capacious. And, just as men’s pockets needed enormous breeches before the three-piece suit divided up their contents, so women’s tie-on pockets required full skirts. The slim, high-waisted silhouettes of the early 19th century, often in the gauziest of muslin, made them impractical. To accommodate the classically inspired fashions of the day, women began carrying small bags known as reticules.

Skirts eventually widened, resurrecting pockets, only to have bustles make them difficult to place. By the twentieth century, most women relied on purses. Derived from sturdy luggage, modern handbags “came to be seen not just as fashionable accessories but as a sign of independence,” writes Carlson. A certain British prime minister famously wielded one, as did her sovereign.

In taking up the pocket gender gap, Carlson answers a question my husband once posed: Why do women carry their cell phones in their insecure back pockets? She cites evidence that the front pockets of women’s jeans are 48 percent shorter than comparable men’s pockets. “Such findings support the contention that midrange fashion is at times driven entirely by aesthetics rather than consideration of wearers’ needs,” she concludes. Women often put their phones in their back pockets because they don’t fit in the front.

The closer she gets to the present, the more Carlson emphasizes runway fashion, where pockets make decorative or social statements rather than seeking to unobtrusively carry stuff. (The book’s cover features a woman with an enormous, utterly impractical red breast pocket on her slim gray 1941 suit.) A call for pocket equality begs for specifics about the design challenges of everyday garments. Are pockets more difficult to fit to women’s bodies? What do designers in the outdoor apparel industry do about women’s pockets? How has the spread of casual, sports-derived clothing changed the pocket calculation? Carlson betrays her academic orientation by focusing on Miuccia Prada and Marine Serre rather than Champion and Columbia Sportswear.

Reading Pockets sent me back to a faded photo showing two smiling blonde girls in matching red plaid dresses. We were best friends, dressed for our first day of first grade in dresses our mothers sewed and hand-smocked for us. Marjory’s dress hangs with graceful symmetry while mine is pulled awkwardly to the right. With a thrust of my hand, I’m demonstrating the subtle difference in the otherwise identical outfits. Mine has a pocket.