Politics

The Return of Terror’s Architect

The restoration of a statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky in Moscow illuminates the gulf that now divides Russian society.

In September, a new statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky was erected in the Moscow suburbs outside of the headquarters of Russia’s foreign intelligence service, the Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki (SVR). Dzerzhinsky was the Polish creator of one of the world’s great repressive political machines. In 1917, he had been instructed to create the SVR’s forerunner, known then as the Cheka, by Lenin himself, who much admired the toughness of the man who became known as Iron Felix. The organisation would be called many names—the GPU, OGPU, NKVD, MGB, KGB—and it is now split into the SVR and the domestic Federal Security Service or Federalnaya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti (FSB).

A statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the #Soviet Cheka (secret police), has been unveiled in Moscow at the headquarters of the Foreign Intelligence Service (#SVR). It is a slightly smaller version of the statue that stood on Lubyanka Square from 1958 to 1991. pic.twitter.com/40TZyJbdju

— Kyle Orton (@KyleWOrton) September 11, 2023

At the statue’s ceremonial unveiling, the SVR chief Sergei Naryshkin said a few words:

Colleagues, the sculpture in front of which we are standing is a somewhat reduced copy of the famous monument to Dzerzhinsky installed on Lubyanka Square in Moscow in 1958.

His winged words, that only a person with a cold head, a warm heart and clean hands can become a security officer have become a significant moral guideline for several generations of employees of the security agencies of our country.

That declaration of Dzerzhinsky’s alleged moral purpose illuminates the gulf that now divides Russia, and the supreme difficulties that its society will face in uniting after the war in Ukraine finally ends.

In an interview with Reuters, Nikita Petrov, a historian at Memorial, a former human-rights centre, expressed the view on the other side of that chasm: “Dzerzhinsky is a symbol of repression and lawlessness. Dzerzhinsky was the head of the first Soviet punitive agency which was guided not by the law but by political will and by a view of the world which divided people into the useful and the harmful.” Memorial was declared illegal in 2021, after years of harassment, but the centre was originally established as the Soviet Union was collapsing in the late 1980s. Petrov worked there to exhume (sometimes literally), identify, and recognise some of the millions of victims of Soviet rule.

Petrov’s remarks, just though they are, were relatively mild. Following the logic of a party that saw most of the Russian population as “harmful,” Dzerzhinsky had set in motion a human cull that destroyed millions of lives over decades. Its victims included numberless priests, members of the higher and lower middle classes, property-owning peasants, and intellectuals of every kind except Marxists. As Dzerzhinsky succumbed to heart failure in 1926, Stalin completed the logic of the punitive state by substituting his own political—and often paranoid—will for any kind of governing process, including by the Party itself, at which point many Marxists were also rounded up.

Born into the impoverished Polish nobility, Dzerzhinsky’s 20s and 30s were consumed by revolutionary organising in Poland, Germany, and Russia. Like other leading Bolsheviks, the ardour of his commitment resulted in harsh punishment and frequent spells of imprisonment, usually in Siberia. These experiences produced a perverse but unbending devotion to cruelty, which he employed in the creation of a new order, ironically intended as the eventual triumph of social ease and personal development.

Dzerzhinsky remained an official hero until the end of the USSR. Even the reformist Mikhail Gorbachev, the last General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party and the Soviet Union’s first and last President, would not have thought of removing him from the pedestal he occupied in front of the KGB headquarters in Lubyanka Square from 1958. The statue, several times higher than the human figure, was created by the famed Soviet sculptor, Yevgeny Vuchetich—a Ukrainian—whose vast creations, always in ultra-heroic poses, still stand across the Soviet Union and beyond. His most famous work is a 12-metre-high statue of a Soviet soldier, a vast sword in one hand, and a German child tenderly cradled by the other, standing on top of a broken swastika in Berlin’s Treptower Park.

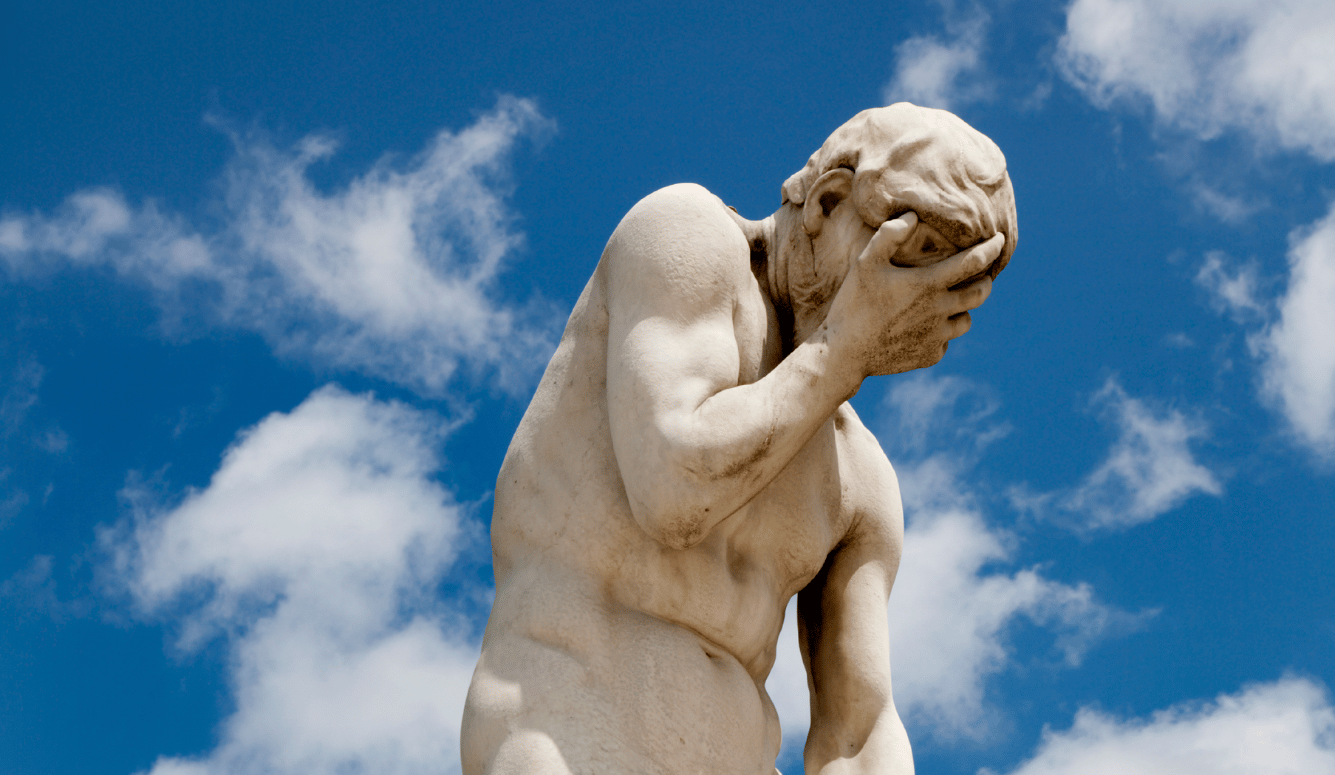

For his statue of Dzerzhinsky, Vuchetich favoured a pose often used in the many Lenin statues—the noble head tilted upwards, looking resolutely into a future he was himself creating. A long coat reached down to his feet, emphasising the subject’s dignity (and simplifying the task of fashioning the body and legs). When I was a correspondent in Moscow, I witnessed the toppling of that statue on a warm summer night of 1991, a few months before Gorbachev resigned. The crowd was numerous but not vast, and mainly composed of young anti-communists.

The crowd threw a rope round the statue and tried to haul it down, but it proved to be as unyielding as its subject. Only when Sergei Stankevich, deputy chairman of the Moscow City Council, introduced an emergency motion to sanction its removal was a heavy-duty crane enlisted to accomplish the task. The statue was lifted vertically from its plinth and placed on a flatbed truck to cheers, shouts, and applause. It was then consigned to a space near Gorky Park, where other statues, mainly of Lenin, had been dumped.

I was cheered by all of this, and said so to Jaromir Stetina, a reporter for the Prague daily Lidove Noviny (and later a Czech MP). Stetina, who had lived his life under Soviet hegemony, did not share the optimism expressed by many Western journalists and diplomats. This was the era of the End of History: liberal politics and neoliberal economics held the policy ring across Europe, North America, and beyond. It was too little noticed that, in China, the Communist Party retained its tight grip—careful loosening of state ownership of the entire economy notwithstanding—and had decided that Gorbachev’s reforms were not a path to be followed.

Stetina thought that the removal of Dzerzhinsky was a welcome development, but that it was of no particular importance. Russia, he predicted, was not a country on the verge of a democratic revolution, but a country whose leaders retained a stubbornly imperialist and authoritarian mindset. Its new leader, Boris Yeltsin, made much of his new friendship with US president Bill Clinton. But although he was a man of courage, willing to shoulder an onerous burden of leadership, Yeltsin was also prone to debilitating bouts of depression and heavy drinking. He did not—and perhaps could not—strengthen a rule of law and new civil society in their vulnerable infancy.

The modest size of the crowd around the fallen secret policeman was testimony to the reluctance of Muscovites to show their support for the statue’s removal. Many preferred to wait and see what kind of post-communist regime would emerge. Celebration was mainly in the West, led by a journalistic liberation narrative of which I was a part. As it turned out, this was a shallow reaction. The book I wrote about that era included many caveats and warnings of deep problems, but I still gave it the unduly optimistic title of Rebirth of a Nation.

Stephen Kotkin, one of the great contemporary American scholars of Russia, has recently published a three-volume biography of Stalin. Kotkin is among those who see Russia as largely unchanged over centuries—a nation that remains deeply averse to democratic institutions and an independent, lively civil society. In an interview with David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker, he was asked if the fear of expansion of NATO had been the principal cause of the invasions of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022. He was categorical: Russia’s imperial and despotic approach was deeply inbred:

What we have today in Russia is not some kind of surprise. It’s not some kind of deviation from a historical pattern. Way before NATO existed—in the nineteenth century—Russia looked like this: it had an autocrat. It had repression. It had militarism. It had suspicion of foreigners and the West. This is a Russia that we know, and it’s not a Russia that arrived yesterday or in the nineteen-nineties. It’s not a response to the actions of the West. There are internal processes in Russia that account for where we are today.

Western states have been mugged by reality. Those who, like me, believed that Russia was open to a move away from dictatorship have largely given up on that illusion. Those still attracted to the country and its president Vladimir Putin are those who believe that authoritarianism is a form of government better suited to a world in crisis than at any time since the Second World War. Democratic institutions have seemed feeble in their own defence, while authoritarian states and parties have, as Freedom House reported last year, “become more effective at co-opting or circumventing the norms and institutions meant to support basic liberties, and at providing aid to others who wish to do the same. In countries with long-established democracies, internal forces have exploited the shortcomings in their systems, distorting national politics to promote hatred, violence, and unbridled power.”

At the same time as authoritarian rule has spread, individuals and institutions in democratic states have taken to self-flagellation for past sins, such as slavery, racism, colonialism, and homophobia, often denying that their societies have changed much. “The west,” the Algerian writer Kamel Daoud has observed, “sees the world through its guilt, as it once saw it through its desire for domination.” And so, a tragic asymmetry has been created. Some of the most ardent spirits in Western democracies are preoccupied with showing that their states remain bastions of prejudice and imperial nostalgia, tearing down or defacing statues to prove their point. Meanwhile in Russia, the Putin regime, which shares much with the worst years of the Soviet Union, has now restored a statue of someone who fashioned the most useful tool of state terror then known. Dzerzhinsky is back on his pedestal to provide a reminder of the terrible power of the Russian regime.

The “moral purpose” Naryshkin invoked when proudly unveiling his predecessor’s new likeness may simply have been a speechwriter’s cynical trope. But more likely it was intended to echo his president’s worldview. Putin has always seen the KGB, in which he had been a mid-ranking officer, as a force not just for order, but for moral good—a boon to the world he sees as inherent to Russia as a whole. “We know,” he said in his annual state of the Nation speech in 2013, “ that there are ever more people in the world who support our position in defence of the traditional values that for centuries have formed the moral foundation of civilization.”

For Putin and those who serve him, morality is whatever advances the state (and the interests of his own regime, in particular). He claims to support Christian and family values, but discards those that might interfere with state governance, imperial expansion, and bloodthirsty war. This was at least more forthrightly admitted by Felix Dzerzhinsky: “We stand,” Dzerzhinsky said in his most quoted speech, “for organized terror—this should be frankly admitted. Terror is an absolute necessity. … Our aim is to fight against the enemies of the Soviet Government and of the new order of life.”

Terror has once again become an integral part of Russia’s rule—terror that has killed thousands in Ukraine, tortured captives, raped women, and seized children for re-education in Russia. This did not need the symbolic replacement of Felix Dzerzhinsky outside the headquarters of the secret police to make the point, but no doubt it helps.