Politics

Unrealistic Realism on Ukraine

Moral relativism, and its equally dubious corollary of moral equivalence, too often mars contemporary Realists’ conceptions of political realities.

General (ret.) Jack Keane recently expressed his worry that, from the start, the Biden administration has quietly favoured “some kind of negotiated deal to stop the war [in Ukraine] as soon as possible.” That, Keane surmises, may be either because certain members of the administration close to the president, like National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, don’t believe Ukraine can win, or because they fear the consequences of Russia’s defeat (which would also explain US foot-dragging in its provision of weapons to the Ukrainians).

If this is the Biden administration’s attitude, it would reflect the growing chorus of foreign-policy experts urging Kyiv to the negotiating table with Moscow as soon as possible. Take Richard Haass and Charles Kupchan (hereafter H-K). Both are or have been professors of international affairs at prestigious American universities; foreign-policy grandees who have held senior positions in government. When they speak, others listen.

In April, H-K co-authored an influential essay for Foreign Affairs titled “The West Needs a New Strategy in Ukraine: A Plan for Getting from the Battlefield to the Negotiating Table,” in which they argue that Ukraine must soon enter into peace negotiations with Russia. What sets their essay apart from earlier and later pieces advancing essentially the same position is its hopeful tone.

H-K hold out the promise of victory for Ukraine, while purporting to show that this outcome is consistent with a hard-headed assessment of the “realities” necessitating a more diplomatic strategy. This strong note of optimism makes H-K’s strategic proposal more persuasive—even to Ukrainians—than basically the same proposal as framed by others. H-K write:

The West needs an approach [to assisting Ukraine] that recognizes these realities without sacrificing its principles. The best path forward is a sequenced two-pronged strategy aimed at first bolstering Ukraine’s military capability and then, when the fighting season winds down late this year, ushering Moscow and Kyiv from the battlefield to the negotiating table.

Yet that rhetorical blend of hopeful and sensible is deceptive. To those who aren’t beguiled by this aspect of their rhetoric, H-K are only marginally less defeatist than others pushing for peace talks, and just as cynical.

The Overall Argument

H-K acknowledge that, since the invasion of Ukraine on February 24th, 2022, the Ukrainians have been fighting valiantly and, with Western support, achieved significant battlefield successes. Nevertheless, for at least two reasons, H-K maintain that Ukraine cannot expect to regain complete territorial sovereignty by war alone. First, the West will soon tire of providing economically costly aid to Kyiv. Second, Putin cannot risk the perception within Russia that he lost the war.

The furthest Kyiv can get by military means alone is a protracted stalemate. That risks the mutual destruction of Ukraine and Russia, escalation into a wider war, and economic dislocations as well as food and energy shortages worldwide.

The Ukrainians should therefore continue fighting, but only until they have rolled back Russian territorial gains in Ukraine as far as they reasonably can. At that point (perhaps before 2024), Kyiv should agree to serious talks with Moscow, overseen by the UN or OSCE. The aims of these negotiations would include a cease-fire, pull-back of all armed forces from embattled territories, and eventually an enforceable peace settlement that restored Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

H-K offer some ideas about how the West could incentivize both Kyiv and Moscow to arrive at a viable agreement. If not full NATO-membership, Ukraine could be offered a security pact with the US and other members that “pledges it adequate means of self-defense.” The Europeans could pour investment into Ukraine to spur its post-war economic redevelopment, thereby facilitating its eventual admission into the EU.

The West could also agree to gradually lift economic sanctions against Russia and normalize relations with the Kremlin, conditional on its good behaviour. If Putin refused to play ball, additional arms would be shipped to Ukraine to help rebuff further Russian aggression, and restrictions would be removed from Ukrainian attacks on key military installations in Russia. Domestically, “Western governments would win renewed public favor for providing such support to Ukraine.”

“This approach [which combines full but not endless Western support for Ukraine’s war effort with diplomacy],” H-K conclude, “may be too much for some and not enough for others. But unlike the alternatives, it has the advantage of blending what is desirable with what is doable.”

Strengths

A major strength of the essay is its discussion of how to interpret and respond to Putin’s nuclear threats. Unlike many other diplomacy-minded commentators, H-K acknowledge that Putin very likely never intended to follow through on those threats. Rather, he calculated that fear of escalation would deter the West from equipping Ukraine with more lethal weapons.

H-K wisely warn that if the West allows its Ukraine strategy to be influenced by the Kremlin’s nuclear sabre-rattling, other anti-Western nuclear powers will be incentivized to use nuclear blackmail to secure foreign-policy objectives. This will in turn unleash nuclear proliferation, as non-nuclear states learn to rest their own security on possession of nukes. H-K also advise the West to accelerate and, where needed, scale up its military assistance to the Ukrainians for their counter-offensive “in the coming months.”

Nevertheless, H-K’s other claims give their argument a very different overall slant—one that signals a further weakening of the West’s already faltering resolve to fully support Ukraine militarily.

The First Problem

First, H-K accept as a given that, absent a change in its Ukraine strategy, the West is bound to tire of supporting the Ukrainians’ defensive war effort. But in that case, how reasonable would it be to repose any confidence in a tired West’s willingness to renew aid to Ukraine if Kyiv were to agree to peace talks but Moscow equivocated? Or if the Kremlin did eventually sign a peace deal but then later reneged, as H-K admit could happen?

Particularly germane here is the Kremlin propaganda machine’s resourcefulness in inventing “justifications” for any predations against Ukraine or invoking “plausible deniability.” Russian persistence in such “disinformation,” coupled with the ongoing opposition to aiding Ukraine from prominent members of the Western commentariat, will further dampen pro-Ukraine sentiment in a West wearying of the burden of prolonging the war by continuing the aid. Yet H-K are strangely silent about this complication.

To compound the problem, H-K say nothing about the civic-educational role of Western leaders in this crisis. What message would a statesman of Winston Churchill’s calibre repeatedly drive home to ward off Ukraine-fatigue? One might have expected H-K to take up the matter, since, as former defence secretary Robert Gates recently pointed out, the Biden administration has thus far failed to fulfill that large educative responsibility.

These glaring omissions and the essay’s specious hopefulness are enough to make one wonder how committed H-K really are to Ukraine’s victory. Consider the following passage, which implies that Ukraine’s victory is now strategically less important to the US than it was earlier:

For over a year, the West has allowed Ukraine to define success and set the war aims of the West. This policy, regardless of whether it made sense at the outset of the war, has now run its course. It is unwise, because Ukraine’s goals are coming into conflict with other Western interests.

Evidently keeping China from invading Taiwan has in H-K’s view emerged as a greater national security priority than helping Ukraine defeat Russia: in Haass’s earliest Foreign Affairs piece on the Ukraine war, China is never mentioned. How, then, are we to understand this apparent change in geopolitical strategic thinking?

One plausible answer is that H-K have never been truly convinced that the West, and the US in particular, had a major stake in the war. American involvement in the war has from the beginning been more a matter of choice than necessity, and were the US to terminate its support for Ukraine, it would cause only minor and tolerable impairment of its national interest. Only now are H-K willing to be more forthcoming about this view, as they seek to refocus Western attention on the more formidable Chinese challenge instead.

A more charitable explanation, intimated in H-K’s essay, is that the war itself has greatly magnified the Chinese threat to Western security. China may now perceive the West’s growing preoccupation with the war in Ukraine as a good time to move on Taiwan.

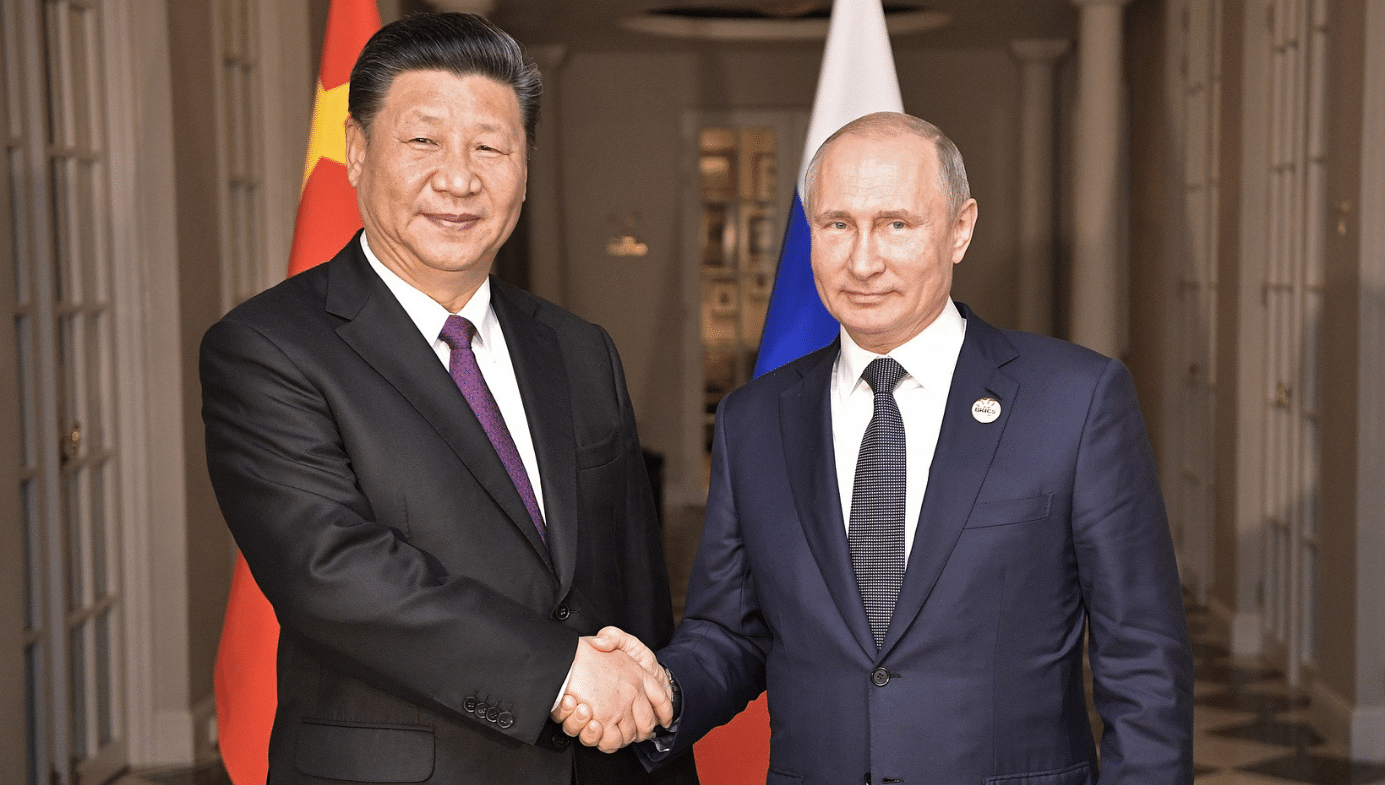

Whatever the explanation, H-K seriously underestimate the gravity of the danger the Russo-Ukrainian war in and of itself poses to the West. They have not fully or clearly grasped that the war is just one of the ongoing Russian, Chinese, and other challenges to the West. Both Moscow and Beijing increasingly perceive these challenges as strategically intertwined in a burgeoning, zero-sum, global clash of civilizations between West and anti-West, with the latter coalescing around the Russia-China “unlimited partnership.”

Nor have H-K reckoned adequately with the concomitant probability that Beijing’s decision about whether or not to invade Taiwan depends in significant part on its perception of how steadfast the West can be in supporting Ukraine’s war effort. The weaker the Chinese perceive the West’s support for Ukraine to be, the stronger their inclination to go after Taiwan. The Taiwanese understand this. Former US State Department counselor Eliot A. Cohen recalls senior Taiwanese government officials telling him that weapons Taiwan had purchased from the US should be dispatched to Ukraine instead.

Hamas’s brutal October 7th assault on Israel, backed by Iran with more distant support from Russia, also begs to be understood as a phase in the global West-anti-West confrontation. Israel has become the second major battlefield on which the anti-West axis, this time with Iran supporting the attack behind Hamas and Hezbollah, seeks to inflict a major defeat on Western civilization.

In an October 8th interview on RT, senior Hamas official Ali Baraka said, “Russia is happy that America is getting embroiled in Palestine. It alleviates the pressure on the Russians in Ukraine. One war eases the pressure in another war. So we are not alone on the battlefield.” What’s more, Iran is using its proxies in Iraq and Syria to achieve its second goal (the first being Israel’s annihilation): to erase the American presence in the Middle East and establish itself as regional hegemon. It’s getting no push-back from Russia or China.

Taiwan could yet become another such battlefield, and it is much more likely to do so if Beijing perceives handwringing irresolution in the West’s handling of radical Islam’s existential threat to Israel and/or Russia’s war on Ukraine. Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin sees these developments as answering his decade-long call for a global clash of civilizations. That possibility appears nonetheless to have eluded H-K.

Those powers of Islamic World who dream still of mediation and normalization of Israeli-Palestine conflict are traitors of Islam and of humanity. The islamic world needs the consolidation and solidarity -- not palliatives that already undermined Islamic unity. Stay strong - form…

— Alexander Dugin (@Agdchan) October 21, 2023

Other Problems

H-K adduce two other circumstances in support of their claim that Ukraine can’t win the war and must soon switch to diplomacy. First, that “the war is eroding the West’s military readiness and depleting its weapons stockpiles.” Second, that China “will not stand idly by as Russia suffers a decisive loss.” This ostensibly amoral and factual analysis smacks of defeatism.

The essay treats these and other such factors as “material” givens, structural vectors of economic and military power, that a priori will determine (in the causal sense of the word) the outcome of the war. The possible choices pertaining to those factors get short shrift. H-K could instead have thoroughly explored what steps the US and its European allies might immediately take to dramatically bolster their own military readiness while applying strong pressure on China to stop backing Russia and refrain from giving it any military aid.

H-K do recommend approaching China to “support [a Western] cease-fire proposal,” but this recommendation, apart from its timidity, is made moot by their tacit suggestion that we can reasonably expect only “an empty gesture” from Beijing. This contrasts sharply with the sanctions the Europeans are planning to slap on Chinese firms for supplying weapons to the Russians.

The Moral Paucity of H-K’s Argument

H-K do make a moral case for the West’s aid to Ukraine, but it is too thin to carry conviction. Presumably because of the admirable “fortitude” and “skill” with which they have waged a “morally justified” war against Russia, the Ukrainians “so deserve” (besides the aid already provided them) full EU membership, albeit only once certain benchmarks have been met.

Yet whatever the grounds of that “desert,” apparently it is not enough to warrant unstinting Western backing for Kyiv up to the point of a just—meaning deserved—Ukrainian military victory. This, despite Western leaders’ repeated moralistic declarations that Ukraine is defending not only its own freedom but also the freedom of the West.

What makes that weak moral case weaker still is the fact that, like so many advocates of a more diplomatic approach to resolving the crisis, H-K are silent about the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. Co-signed by the US, UK, and the Russian Federation, that agreement provides security assurances against threats to Ukraine’s “territorial integrity or political independence,” in exchange for the voluntary surrender of its nuclear weapons.

By neglecting to mention the memorandum, notwithstanding its obvious importance, H-K betray their wish to minimize the weight of America’s obligation to Ukraine. Their silence is consistent with the ultimate effect of their overall argument, which is to pry apart the US and Ukraine, especially militarily, irrespective of what the obligation might entail.

Moreover, even as H-K sweep the Budapest agreement under the rug, they enjoin us to give peace negotiations with a demonstrably untrustworthy Russian adversary a chance. Others say explicitly what H-K will not, but their argument nonetheless tacitly indicates the same conclusion: for negotiations with Russia to succeed, Kyiv must be “[willing] to make some concessions,” including territorial ones. Which is to say that Russia would ultimately be rewarded for its extreme injustice to Ukraine. It is hard to imagine anything more cynical, however camouflaged.

A Possible Realist Rejoinder

International-affairs professor Emma Ashford gives this succinct description of foreign-policy Realism:

Although the school of thought comes in a variety of flavours, nearly all realists agree on a few core notions: that states are guided primarily by security and survival; that states act on the basis of national interest rather than principle; and that the international system is defined by anarchy.

Accordingly, what may appear to non-Realists as cynicism or defeatism will be said by Realists to be dispassionate recognition of non-negotiable constraints of political reality, stripped of unreasonable hopes and moral expectations.

We need not delve into the intricacies of Realist theory, such as the similarities and differences among Classical, Structural, and Neoclassical Realisms. If Realist approaches to Ukraine, like the diplomacy-oriented approach examined here, fall wide of the mark, then it’s no saving grace that they are proffered as applications of clear-eyed pragmatism. Indeed, they should be rejected as insufficiently realistic.

Earlier proponents of Realism, foremost among them American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, “grappled with how to recognize that all human action is tainted by self-interest while avoiding the paralysis of moral relativism.” Yet as political scientists John Owen and William Inboden also point out, this same moral relativism, and its equally dubious corollary of moral equivalence, too often mars contemporary Realists’ conceptions of political realities. This is evident in their failure to refute the false but popular maxim “Might before Right,” a crucial effect of which is to devalue a key rhetorical advantage the democratic West possesses over its anti-democratic enemies.

A Stronger, More Realistic Strategy

Even on their own amoral, power-centric terms, foreign-policy Realists like Haass and Kupchan are not realistic enough.

As historian and political theorist Walter Russell Mead argues, emboldened anti-Western powers are, with increasing speed and coordination, probing the West’s weak points to cause disruption or destruction by any expedient means. This includes the use of war and terror—as already in Ukraine, now in the Middle East, perhaps later in Southeast Asia. The overall strategic aim, more or less consciously shared, is to break apart—a lot or a little at a time, as circumstances permit—the Empire of Liberalism and replace it with their own expanded spheres of hegemony.

The US and its allies must therefore be firm in simultaneously blocking the expansionist efforts of Russia, China, Iran, and other anti-Western actors. That is what “containment,” a strategy NATO deployed largely successfully against the Communist bloc during the Cold War, will mean today. The West’s long-term “security and survival” require no less.

Thus, any real victory for Putin, be it obtaining from NATO a promise to deny Ukraine membership, or retaining, with or without a peace settlement, control over some Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine, will be a major setback for the West. It will show the world that invading one’s neighbours, though unjust, can yield substantial material gains, and that the decadent West is at bottom too weak to defend its values and fight for its interests and friends, and too ready to appease its foes.

On the other hand, confronted with a toughened, resolved, re-armed West mobilized in the defense of its liberal civilization through (among other measures) robust military support for Ukraine, Beijing will be that much more wary of risking a similar confrontation with the West over Taiwan or elsewhere. Iran too may be checked. The as-yet unaligned Global South will be more inclined to align with the West than with China or Russia. The West’s position in its global Kulturkampf with the tyrannical, anti-liberal anti-West will become far more powerful.

Consistent with this more truly realistic, “clash of civilizations” line of reasoning, military historian Frederick W. Kagan proposes promptly giving Ukraine all the military and other aid it needs to drive Russia out of the country completely, while helping Taiwan prepare for a potential Chinese attack:

Other analysts similarly implore Western policymakers to think through how best to assist Ukraine militarily, possibly for years after the current offensive. Some fear “Western countries have not effectively signaled their commitment to a prolonged effort,” because of which “Moscow could assume that time is still on its side and that bedraggled Russian forces can eventually wear down the Ukrainian military.”

“There is time,” says Eliot Cohen, “for clever policies, subtle diplomacy, considered overtures, and exquisite compromise. This is not it.”