Politics

Mind the Gap

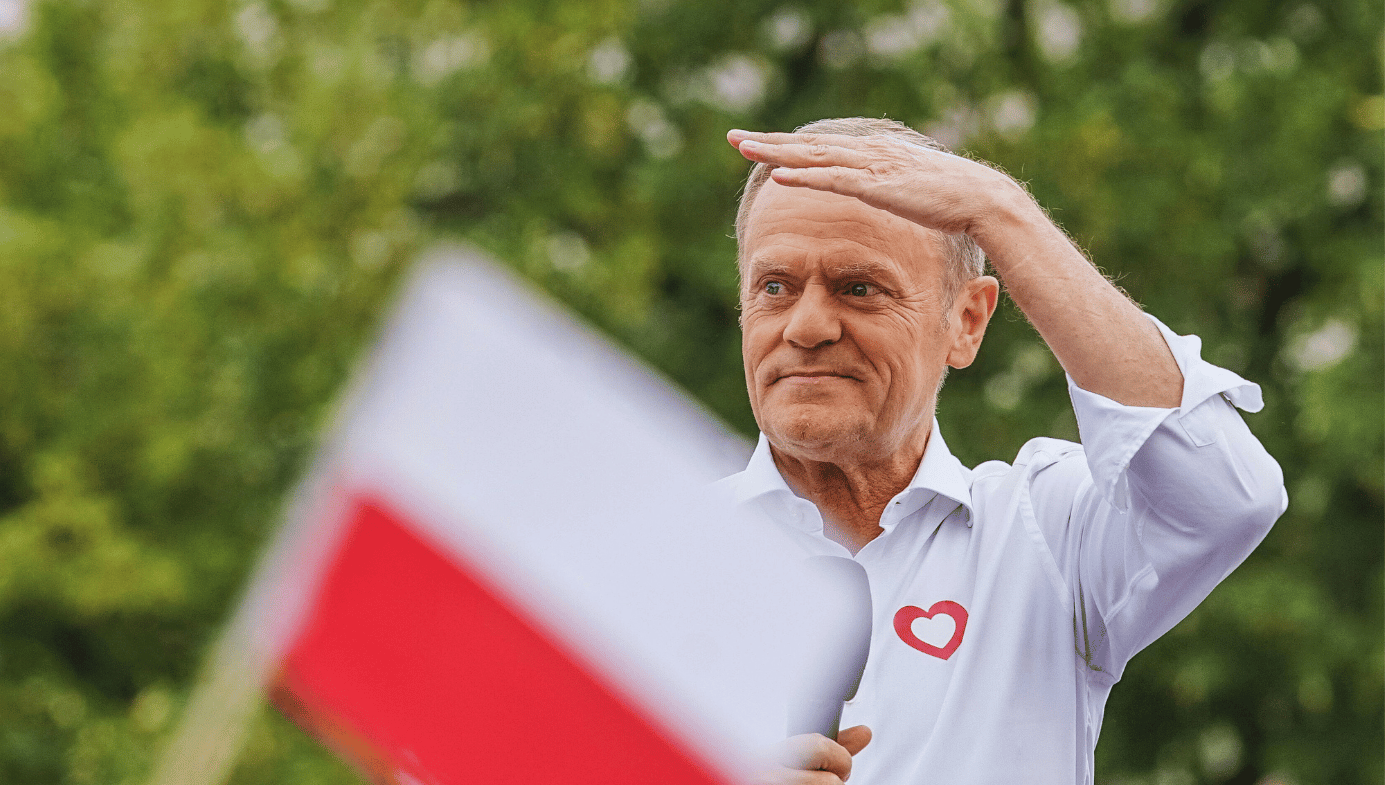

If he is to reunite Poland, Donald Tusk will have to balance his strong support for the EU with citizens’ legitimate concerns about the erosion of national sovereignty.

The citizens of Poland have voted. A government that combined conservative Catholicism with “soft” Euroscepticism (they won’t leave the European Union but they despise it) will now likely be replaced by a government led by a passionate EU advocate. This will be as radical and wrenching as Donald Trump’s assumption of US power in 2017 after eight years of Barack Obama.

Radical and wrenching political transformations are presently in vogue. The Fratelli d’Italia party dominated the September 2022 election in Italy and brought Giorgia Meloni to power—a politician of a conservative-nationalist Right unknown in Italy since World War II and determined to amplify its country’s voice in the EU. In France, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (formerly the Front National) occupies the same political space as Meloni’s party. Le Pen is presently the favourite to win the next presidential election (though it will be 2027 before she has a chance to either prove her popularity or see her third attempt at winning that contest fail). The right-wing coalition government in Sweden has, over the past year, cut away at the social-democratic consensus with which the country has been identified for decades. Among large European nations, only the UK expects to see a victory for the centre-Left Labour Party next year, with very little change to economic and social policy likely.

For almost a decade, Poland has been deeply divided. In part, this is because Poles living in small towns and country villages prefer the pious nationalism of the Pravo i Sprawiedliwosc (Law and Justice) Party led by Jaroslaw Kaczyński, who is deeply religious and harbours a stony hatred for Russians and Germans. Polish urbanites, on the other hand, largely vote for centrist and left-wing parties. Among these, the major force is the Platforma Obywatelska (Civic Platform) of Donald Tusk, a former prime minister (2007–14) who is as strongly wedded to the EU as Kaczyński is to conservative Catholicism. During the campaign, Kaczyński repeatedly alleged that Tusk is a stooge acting for European (especially German) interests. The opposition side, meanwhile, depicted the Law and Justice government as a monstrous institution, determined to drag Poland into a deeper and more all-embracing authoritarianism than exists in Viktor Orbán’s Hungary.

Nearly two weeks before the vote, I attended a vast protest march in Warsaw’s centre, which ended beneath the grandiose Soviet-built Palac Kultury i Nauki (Palace of Culture and Science). Seeing the gathering, and walking beside it for a time, offered a glimpse of the PiS’s manipulation of the media. Several hundred thousand people marched that day—not a million, as Tusk claimed, but certainly many times more than the 60,000 reported by state media, which barely featured the multitude in its news programmes.

A young woman named Dominika—a lawyer who helped me with an unfamiliar language and a recalcitrant ticket machine at the metro—earnestly asserted that this would be the last chance for those opposed to the Law and Justice to vote. There would be no next time. The day after the vote, she sent me a text: “I told you we must win the elections. Today is a new beginning for this country, it is the most important moment of this century. We are back! We won!” Those words echoed the post-election rhetoric of Tusk himself. “We won democracy,” Tusk declared at a rally after the results were announced. “We won freedom, we won our free beloved Poland. … This day will be remembered in history as a bright day, the rebirth of Poland.”

Law and Justice remains the largest party by some distance, but it has few, if any, allies among the smaller parties. Tusk does have allies, and this will enable him to forge a coalition with considerably more seats in parliament than PiS can muster. But he will have to change his tone: for a future leader of the country to frame his victory as rescuing democracy, freedom, and the state itself from the clutches of the present government will only widen the gulf that the past decade has opened up in Polish society. That gulf must be narrowed if a new administration is to enjoy nationwide legitimacy, and if democracy itself is to continue.

Much of the responsibility for that gap-narrowing will fall to PiS. Its campaign described the opposition parties as something like traitors to the state, which would make their supporters complicit in national treachery. It has been PiS that has cowed nearly all the media channels into subservience; it has been PiS that has made abortion illegal in all but the most extreme circumstances (a damaged or dead foetus); it has been PiS that encouraged dislike of gays and others by declaring “LGBT-free zones”; it has been PiS that manipulated the constitutional and other courts to suit its political agenda, prompting the EU to withhold €24 billion in grants and €12 billion in loans from the pandemic recovery programme.

At the heart of that dispute with the EU, however, is a battle over which law, European or national, should take primacy in the event of a conflict—a battle by no means confined to Poland. Piotr Müller, the Polish government spokesperson, has said that “the supremacy of constitutional law above other legal systems stems literally from the Polish constitution.” Hungary likewise believes that its law is supreme. Italy’s Meloni is reluctant to tangle with an EU that is providing it with record amounts of recovery funds. Nevertheless, she plainly favours Italian law’s primacy and is testing the strength of the EU’s veto on the matter.

The issue is an existential one. The EU is likely to avoid a showdown with Poland now if, as expected, the PiS government is replaced by the Civic Coalition of parties. But in the Union’s presently febrile state, the quarrel over sovereignty is certain to arise elsewhere, as other nations and powerful right-wing parties chafe at their loss of legal supremacy. This is a fight the EU cannot afford to lose. It believes that:

[W]here a conflict arises between an aspect of EU law and an aspect of law in an EU Member State (national law), EU law will prevail. If this were not the case, Member States could simply allow their national laws to take precedence over primary or secondary EU legislation, and the pursuit of EU policies would become unworkable.

This, more than any other argument between Brussels and the member states, is the one which most strongly reminds the member states that they are subservient to the Union. It is at once the EU’s strongest card and its weakest link. A strengthening of the Eurosceptic New Right parties, coupled with a loss of momentum in Brussels, will likely result in further attempts to limit integration, and even to take back powers the states have surrendered, including the primacy of domestic law within their own borders.

Tusk strongly believes in the primacy of EU law, but must try to reunite a fractured country which has, under PiS, been taught to see the European Union as more of a threat to sovereignty than a family of which its citizens are proud to be members. The PiS leaders, Kaczyński and Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, have worked hard to reduce the EU’s pretensions to greater power. In a speech earlier this year, Morawiecki gave a succinct view of a Union seeking power at the expense of nation states: “Smacking others with the whip of ‘European values’ without agreeing on their definition or understanding what changes must be made by particular countries is […] self-destructive for the European Union. … Do we really want a pan-European cosmopolitan elite with immense power but without an electoral mandate?”

Tusk could only view such a speech with contempt; his commitment to the EU and further integration is total. After his first period as prime minister, he moved to Brussels to become president of the European Council, the body which brings together the leaders of the member states. In that capacity, he was dismayed by Brexit, calling it “one of the most spectacular mistakes in the history of the EU” and “the most painful and saddest experience” of his five years in the president's office. He blamed David Cameron, who was then UK prime minister, for the “mistake” of organising a referendum “he had no chance to win,” and even asked the British prime minister if the result was “reversible.” When the two men spoke the morning after the vote, Tusk was still hoping that the decision could be undone. Saving the UK from Brexit, by whatever means, was more important to him than observing the result of the referendum, which Cameron had said would be binding.

But Tusk is flexible enough to change his mind. He once believed, as PiS still does, that abortion ought to be severely limited, and only moderated that view when he returned from Brussels to lead the opposition. He may yet leave at least some of his passion for the EU’s further integration behind him as he shapes a premiership not too antipathetic to disappointed PiS voters. The Euroscepticism of the departing government ran deep and is shared, at least to some degree, by many of the smaller nations and by the growing ranks of the far-Right continental parties.

In Poland, I spoke with former PiS government minister Ryszard Legutko, a conservative intellectual, university professor, and close ally of Kaczyński. The “extreme polarisation” in his country, he says, is “very violent—I see it between the forces for sovereignty, and those who want Poland to become totally dependent on external institutions, [such] as the EU or other European countries” (by which he means Germany). In a speech he delivered in the European parliament earlier this year in the presence of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Legutko stated that Europe is ruled by “the big guys, and the biggest of these is Germany. They never bother to consult anyone, and they call that leadership.” He laid two grave mistakes at Germany’s door—opening Europe to mass immigration (in 2015, during Angela Merkel’s chancellorship) and the “long and murky political romance” with Russia, largely aimed at securing cheap energy.

PiS and Kaczyński overplayed the German and Russian cards, laying every sin of omission and commission at the doors of both. Nevertheless, memories remain strong of Poland’s violent bifurcation and occupation during World War II, and of the Soviet Union’s ruthless imposition of communism, even among those with no direct experience of that era. One of the PiS policies that Tusk has said he will continue is the demand for reparations from Germany for that occupation—a demand estimated to be US$1.5 trillion, a third of that country’s GDP.

Still, Tusk's enthusiasm for the Union will likely benefit him as prime minister, particularly among the highly educated and young. Poles accept the EU (though they have not adopted the euro currency) and would be very unlikely to vote for a Polexit. But the desire for real sovereignty remains following centuries of foreign oppression and the dismemberment of the country by Austria, Prussia, and Russia for over 120 years at the end of the 18th century. Poland’s fraught and bloody history has understandably made its citizens protective of their country's sovereignty. If Tusk deploys his undoubted political skills to good effect, he may be able to heal the country’s deep political fissure. But he will need to set a limit on the “Europeanisation” of his country if he is to reassure his fellow citizens that self-governance will be safe in his hands.