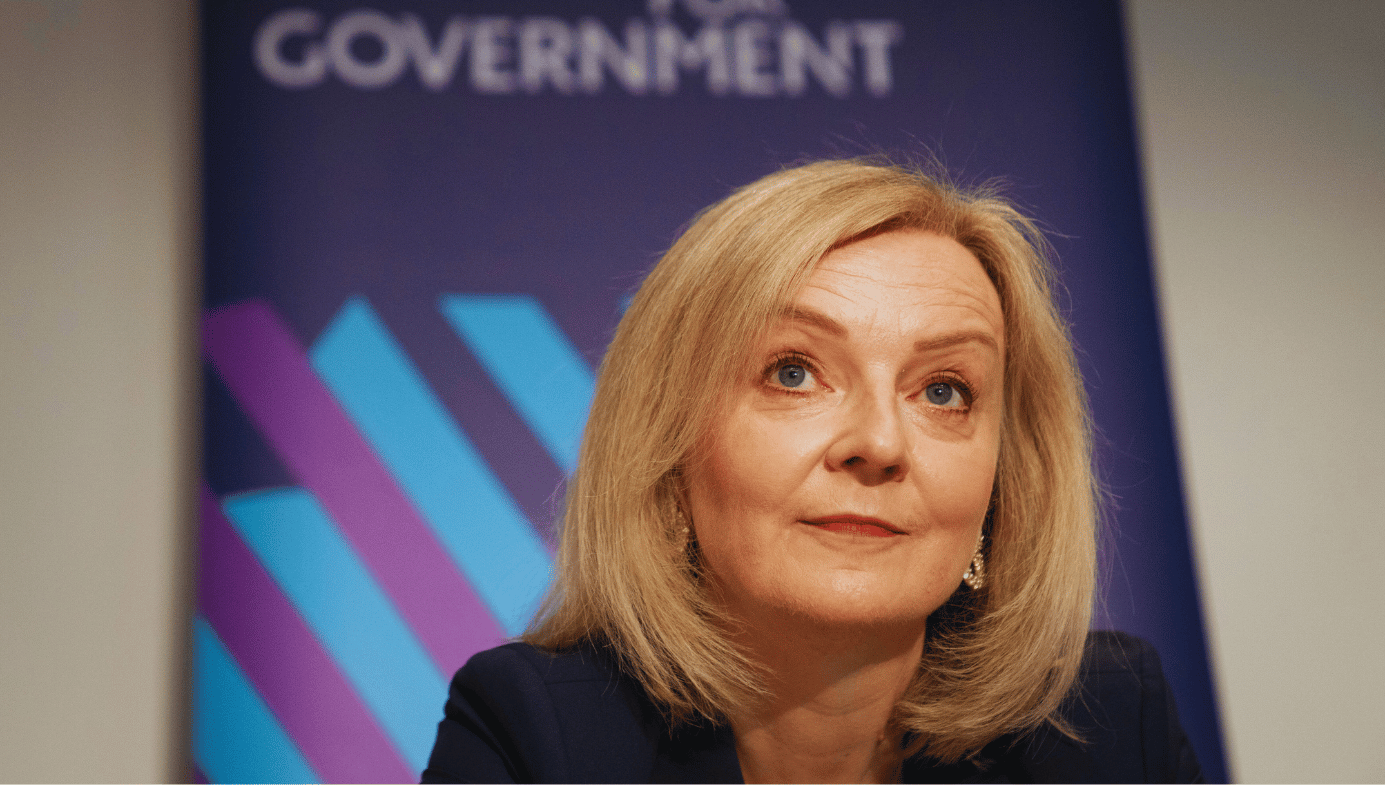

The Disaster Artist

Was Liz Truss Britain’s first affirmative-action prime minister?

When Britain’s liberal commentariat delivered its postmortem on Liz Truss’s prime-ministerial car crash last year, incompetence was the salient theme. “Never has a prime minister been less suited to the job than she was,” declared a Guardian editorial. Her 45 days in office had been “the most belligerently incompetent British prime ministership in modern, and perhaps any other, times.” In the New Statesman, Martin Fletcher branded Truss “the worst Tory prime minister yet”; “Inept, tin-eared and seemingly devoid of any emotional intelligence,” she had reduced Britain to “an economic basket case, a global laughing stock, a byword for shambolic government.” At the Independent, Sean O’Grady concluded that Truss simply “didn’t possess the skill set that would have made her a competent—let alone inspiring—leader.” She was “wooden, intellectually dull, weak and incompetent,” all of which had been “perfectly apparent during the leadership campaign.”

Exuberant as these denunciations were, few would deny the point: Liz Truss is a dismal politician. Though she may well have been correct in her assessment that Britain’s bloated state was a recipe for decline, her tax-cutting mini-budget spooked the markets so badly that the pound tumbled to its lowest ever level. When she addressed the nation on the day the Queen died, Truss’s awkward delivery from the Downing Street lectern was comically unsuited to the solemnity of the occasion. Her handling of her own party was little better. Colleagues reported that they could never get hold of her, and by veering between massive tax cuts and a huge package of energy subsidies, she managed to alienate both wings at once. In a final flourish, still reeling from her mini-budget climbdown, she toppled her own premiership by making a controversial vote on fracking a motion of confidence in her teetering government.

How did someone so manifestly unqualified to be at the top of politics end up there? The title of Truss biography Out of the Blue reflects the now-conventional view that her unlikely career was some kind of freak weather event. Reviewers of this sympathetic portrait, hastily completed last autumn by the Sun’s political editor Harry Cole and Spectator diarist James Heale, have noted the warnings that went ignored, her “contrarian personality,” and the fact that she “had got away with so much in the past, leading to an overconfidence about her ability to wing it.” All of which is plausible enough, as far as it goes. However, what the UK really needs, writes the Guardian’s Gaby Hinsliff, is “a more unsparing account of what allowed a politician so flawed to rise so high at the expense of us all.”

Amid all the commentary on Truss’s rapid rise and precipitous fall—which one year on blames either her free-market purism or the Whitehall “Blob,” according to political taste—one key component of her career has been conspicuous by its absence. Truss’s rise coincided with the “modernisation” era of Conservative leader David Cameron. And because she is a woman, Truss benefitted from preferential treatment within her party and sympathetic treatment in the media, even from traditionally hostile papers, in spite of numerous gaffes and failures. The liberal press may now wax apoplectic about Truss’s uselessness, but it surely protests too much—after all, it did so much to foster the tokenistic political climate that put her there.

Largely compiled before her downfall, Out of the Blue does actually make this clear to anyone who cares to notice. When David Cameron was elected Conservative leader in 2005, he introduced his “A-list” as part of an effort to remodel the party along the lines of Tony Blair’s incumbent New Labour and make it less male, pale, and stale. Truss, having stood unsuccessfully for Parliament in 2001 and 2005, was swiftly added to it. In 2009, she was parachuted into the safe rural seat of South West Norfolk for the forthcoming 2010 General Election, and selected by a vote of the local Conservative Association. However, the constituency executive had not been informed that she’d had an 18-month affair with Tory MP Mark Field when they campaigned together in 2004–05. Aggrieved, the committee voted to deselect her. Truss’s career appeared to be over before it had begun.

This simply would not do for Cameron’s favoured candidate. An ally admits: ‘‘We were putting through the modernisation and this was just not going to be allowed to happen. We regarded it as sexist to deselect this person.” A team was duly dispatched to the seat by party headquarters as the national media arrived ahead of the crunch vote of members. On the eve of the vote, Cameron issued an ultimatum: if it did not go Truss’s way, he would put the association into special measures and suspend its executive committee. The association chairman—who had been staunchly opposed to Truss after her affair came to light—flipped and threw his weight behind her. Truss avoided deselection.

Though clearly no mark in her favour, whether or not Truss’s affair ought to have disqualified her from office is secondary here. Truss had come to symbolise more than her own political career, and this enabled her to escape the usual rules of politics. (Just two years prior, James Gray, Conservative MP for North Wiltshire, narrowly avoided deselection by his association after he cheated on his wife and the mother of their three children while she had breast cancer. Cameron pointedly remained neutral ahead of the vote.) Those opposed to Truss’s rise were ridiculed as outdated Tory “traditionalists” and cruelly dubbed the “Turnip Taliban.” As a young liberal woman, Truss, meanwhile, came to represent “modernisation,” and Cameron enjoyed a good deal of positive press when he backed her.

This dynamic continued throughout her career. After he assumed power as head of a coalition government in 2010, Cameron made Truss a junior minister for education in his 2012 cabinet reshuffle. Cole and Heale are candid about the reasoning behind that decision: it was “clinically designed to neuter claims Downing Street had a ‘women problem.’” New female appointees were duly met with praise in the press, and hailed in the left-wing Independent as “the rapid rise of Cameron’s new girls.”

More from the author.

Cole and Heale are clearly aware of the role played by Truss’s sex as her career was given another boost during Cameron’s July 2014 cabinet reshuffle. “With polling day then just 10 months away,” they write, “... [t]he plan to add more women around the table had already been briefed far and wide.” Before his election, Cameron had pledged that a third of his ministers would be women in the next parliament, and he was under pressure to deliver. Accordingly, Cole and Heale recount that, on the morning of the reshuffle, Cameron decided to promote Truss to the cabinet position of environment minister, a decision the former PR man would later describe as “gut instinct.” “I looked at people like [Truss and others],” Cameron recalls of the reshuffle in his autobiography, “and saw the modern, compassionate Conservative Party I had always wanted to build.” (Was this a sober recognition of her record at Education, where Truss’s main achievement had been a childcare policy that, in the words of Cole and Heale, “crashed and burned”?)

Even though Truss had clearly been the beneficiary of preferential treatment, by the next paragraph of Out of the Blue, Cole and Heale are dazzled that she had managed to smash another glass ceiling: “Be it divine intervention, or a twist of fate, or the recommendation of [her boss, Michael] Gove,” they write, “Liz Truss walked up [Downing Street] and into the history books as the youngest-ever female Cabinet minister at just 38.” Part of this reaction can be explained as gloating from right-leaning journalists who enjoy pointing out that the Conservative Party has met landmarks of representation before Labour. But Cole and Heale also reflect the attitude of the legacy media towards affirmative action.

Affirmative action is often used to placate media criticism, and politicians may even announce sex- or race-preferential appointments explicitly and be praised for doing so. Lavish praise then follows for the appointee, who is somehow held to have struck a “historic” blow for representation. But how can box-ticking be considered ground-breaking female advancement? Such cognitive whiplash reflects a phenomenon that former Trump administration official Michael Anton calls “salutary contradiction”: a rhetorical move that allows apologists for something unpopular to maintain two contradictory positions at the same time: “That’s not happening and it’s good that it is.”

Cameron’s A-list kicked off affirmative action in the Conservative Party, but Truss also benefitted from the tokenistic hiring policies of Cameron’s successor, Theresa May, who has since described herself as “woke and proud.” When May took power in July 2016 after Cameron’s post-referendum resignation, it was widely briefed that she was “determined to ensure that her cabinet comes as close to full [gender] parity as possible.” Truss was duly appointed as the youngest ever Justice Secretary and Lord Chancellor, despite the PPE graduate having no background in the law.

At this point, Cole and Heale write, faced with questions about her lack of expertise and seniority, Truss “played the sexism card.” A briefing she authorised labelled her critics “old white male judges and politicians” who displayed “thinly veiled misogyny.” The press lapped it up and Lord John Thomas (who was then Lord Chief Justice) hailed Truss’s appointment as “historic”: a “long-standing monopoly has been swept away,” he proclaimed, “and it is plainly not before time.” By the following year, he was singing a different tune before a Lords committee, where he accused Truss of having “misunderstood … completely” her own department’s rollout of a policy on rape trials, which meant he had to write to judges to explain that a ministry press release was incorrect. Cole and Heale explain this “softly spoken drive-by shooting” as the revenge of Britain’s Remainer judiciary (still smarting after Truss’s refusal to denounce an infamous tabloid front page that labelled Brexit-blocking justices “Enemies of the People”). But whether or not it was a partisan pot-shot, Truss’s hapless record at the Ministry of Justice provided no shortage of ammunition to her critics. “She made mistakes there,” a friend surmised; “she alienated everyone.” After the following election, Theresa May demoted Truss to junior cabinet minister.

The demotion notwithstanding, Truss was now milling around the top of Conservative Party politics. In 2019, a newly crowned Boris Johnson promoted her to international trade secretary after she backed his leadership bid. By spring 2021, Johnson was also under pressure to promote more women. He pledged to “improve how representative his Cabinet is of the population at large,” and announced that he is a “feminist.” Accordingly, in his September reshuffle, he promoted Truss to Foreign Secretary (a move that resulted in a glowing profile in the New Statesman). From there, helped along by hundreds of taxpayer-funded Instagram snaps of her travels, Truss was able to generate a big enough profile to win last summer’s leadership contest.

It is a long way from prole to PM, and there are doubtless other factors behind Truss’s rise. Nevertheless, the benefit her sex had on her career is surely indisputable. Each prime minister she served under explicitly promised to promote more women to cabinet positions. Again and again, Truss’s career progress was offered as evidence of her party’s “modernisation” in spite of her weak record and she was treated with kid gloves in the press. On the rare occasions that she faced resistance, she trotted out the ready cry of “sexism” to silence critics. (Even at last summer’s head-to-head debate between leadership candidates, after Rishi Sunak slammed Truss’s tax plans with a barrage of facts and figures, the Truss camp accused the former chancellor of “mansplaining,” as did much of the media.)

Was Truss’s time in the spotlight at least good for women’s advancement? “We all know that the stereotype of women as Instagram-obsessed intellectual lightweights lacking gravitas or charisma is outdated and unfair,” despaired New Statesman writer Pravina Rudra in August 2022. “So it’s immensely frustrating to watch Truss play into so many of these sexist tropes, making people suspect they might carry some weight.” This is the inescapable irony of affirmative action—by over-promoting the under-competent, it creates the very seedbed for such views. The problem is not that women cannot be strong leaders (Margaret Thatcher, who Truss so unconvincingly tries to emulate, is surely evidence enough of that), it’s that those who have to fight their way to the top will, by and large, be more competent than those who are given an easy ride. That is why politicians should be judged on the quality of their leadership, not on the accident of their identity. Doing otherwise only devalues the achievement of those who actually do deserve to be there.

The very question of “women's advancement” requires us to view individual female politicians as representatives of women in general—a supposedly monolithic political category, whose interests are presumed to be the same. In reality, Truss’s rise was good for one woman and one woman only: herself (though the honour of being the UK’s shortest serving prime minister ever is surely a dubious one). To consider Truss’s high-flying a win for women as a whole is to subscribe to a collectivist mindset over a meritocratic one that values individual talent and ability. It asks us to believe that a woman, say, opposed to Truss’s economic agenda or disdainful of her weird speeches, should nonetheless support her simply because they're the same sex. Reductive as this worldview is, Rudra’s article demonstrates just how firmly entrenched this kind of thinking has become. At the end of a biting polemic, she nevertheless admits: “I want to support Liz Truss … [because] she is a woman.”

One might simply conclude that all this reveals the shallowness of modern democracy. Today’s politicians often seem to be mere figureheads: a media presence, an impression in voters’ minds, someone to cut a ribbon or deliver a speech written by someone else. The average voter will seldom have any idea how good a politician is at the daily task of managing a department or a party, most of which will be done by officials anyway. So while this dispiriting reality shouldn’t excuse tokenism, perhaps it goes some way to explaining it—if politics is mostly image, why not favour the faces that generate the best headlines?

In fact, it isn’t only a politician’s public image that counts. As the chaos of last autumn demonstrated, top politicians do get their hands on a lot of real power. If they end up being mismatched to the job, everyone suffers for it. This will be worrying news indeed to a Western intelligentsia increasingly preoccupied with engineering equal outcomes around race, sex, and sexuality. If Liz Truss’s car-crash premiership is to be a cautionary tale, let it be one about the dangers of affirmative action.