So-Called Dark Ages

King of the Goths

In the third instalment of ‘The So-Called Dark Ages,’ podcaster Herbert Bushman describes the rise of Alaric I, whose Gothic armies roamed Greece and the Balkans before marching on Rome itself.

What follows is the third instalment of The So-Called Dark Ages, a serialized history of Late Antiquity, adapted from Herbert Bushman’s ongoing Dark Ages podcast.

When we left off at the end of the second instalment, we saw the Goths victorious at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 C.E., having killed the Roman Emperor Valens (r. 364-378) and destroyed his army. The Balkans were exposed, and general war followed. In this instalment, I’ll summarize the course of that war, before introducing the man referenced in the title: Alaric I, King of the Goths.

The demise of Valens set off four years of chaos in the middle part of the Empire. After the failed siege of the town of Adrianople (now Edirne, in modern Turkey), the Goths, led by Fritigern, advanced on Constantinople, the formidably defended eastern capital of Rome’s Empire. Exactly what they thought they would accomplish there, without the necessary siege engines, is unclear. Perhaps the adrenaline of victory was still making decisions for them.

We have to remember that most of the men in the Gothic army would have only heard stories of the capital. They’d gotten very close to capturing Adrianople, so maybe anything seemed possible.

When they drew near to Constantinople and saw the extent of the walls and size of the city, however, reality was a dash of cold water. A siege was begun, but ended quickly when a squad of Arab foederati charged out of the gates and attacked the Gothic camp. One—stark naked, according to accounts—slit a Gothic warrior’s throat and drank his blood. At this point, the Gothic siege (understandably) dissolved in horror.

In Valens’ absence, command of the eastern half of the Empire fell to his magister militum—master of soldiers, or commander-in-chief—a man by the name of Iulius. His reaction to the defeat at Adrianople was not calculated to de-escalate the situation. Rather, he sent out orders to all garrisons in Thrace to massacre their Gothic federate troops, which they did. Once that slaughter became generally known, riots broke out among Gothic communities across Asia Minor, which were put down with similar brutality.

Ultimately, this was just a recruiting opportunity for Fritigern, as uncommitted Goths across the region flocked to his banner. Better to hang for a wolf than a lamb.

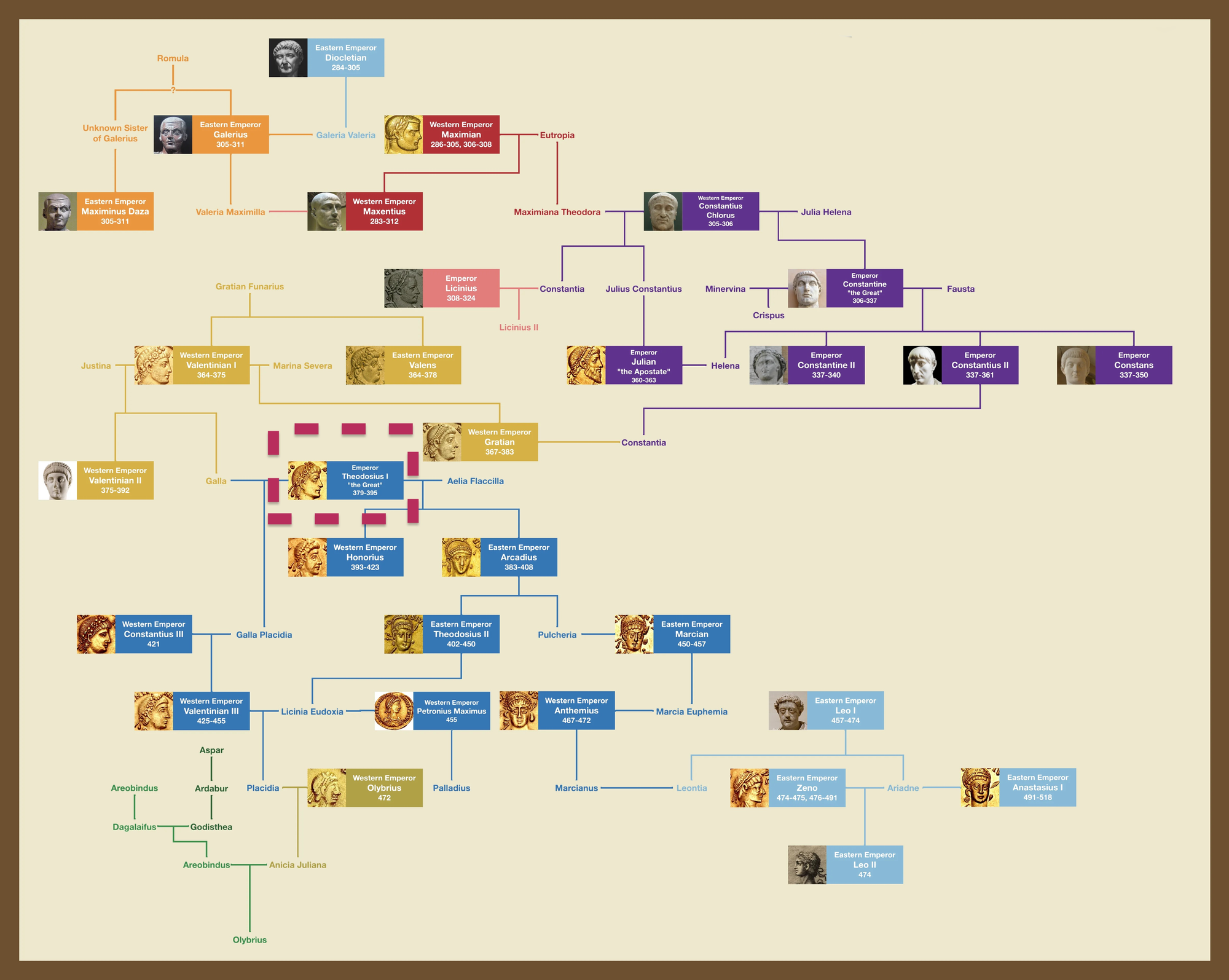

The next four years are a confused historical jumble, with sources often absent or contradictory. Overall command of Roman troops was given to Theodosius, a commander who had been successful against the Sarmatians earlier in his career. In January of 379 C.E., after a few months’ probationary period, he was invested with Imperial powers. No one knew it, but the last continuous dynasty of Roman emperors was being created at that moment.

Theodosius then moved to rebuild the shattered army. But his initial attempts were disappointing, as many of the farmers who might otherwise have been conscripted were hidden away by their landlords (a harbinger of the localized feudal reflexes that would be transforming Europe in coming centuries). And the first proper field army that Theodosius did manage to field simply ran away at first sight of the enemy. Theodosius responded with a massive propaganda effort to build up even minor victories, so as to create the impression that he was making progress against the Goths.

For their part, the Gothic forces had problems of their own. Fritigern found that it was nearly impossible to feed his men when they were gathered together in one place, so he was obliged to split his forces up into smaller groups to forage. That made them more vulnerable to Roman counterattack. And even when all of Fritigern’s forces were able to congregate, they found themselves unable to take the region’s larger walled cities, which might have provided bases of operation for a long-term campaign. So, in spite of an influx of Gothic fighters from the countryside, as well as Sarmatians, Taifali, and even Huns, from over the border, Fritigern found himself mostly treading water.

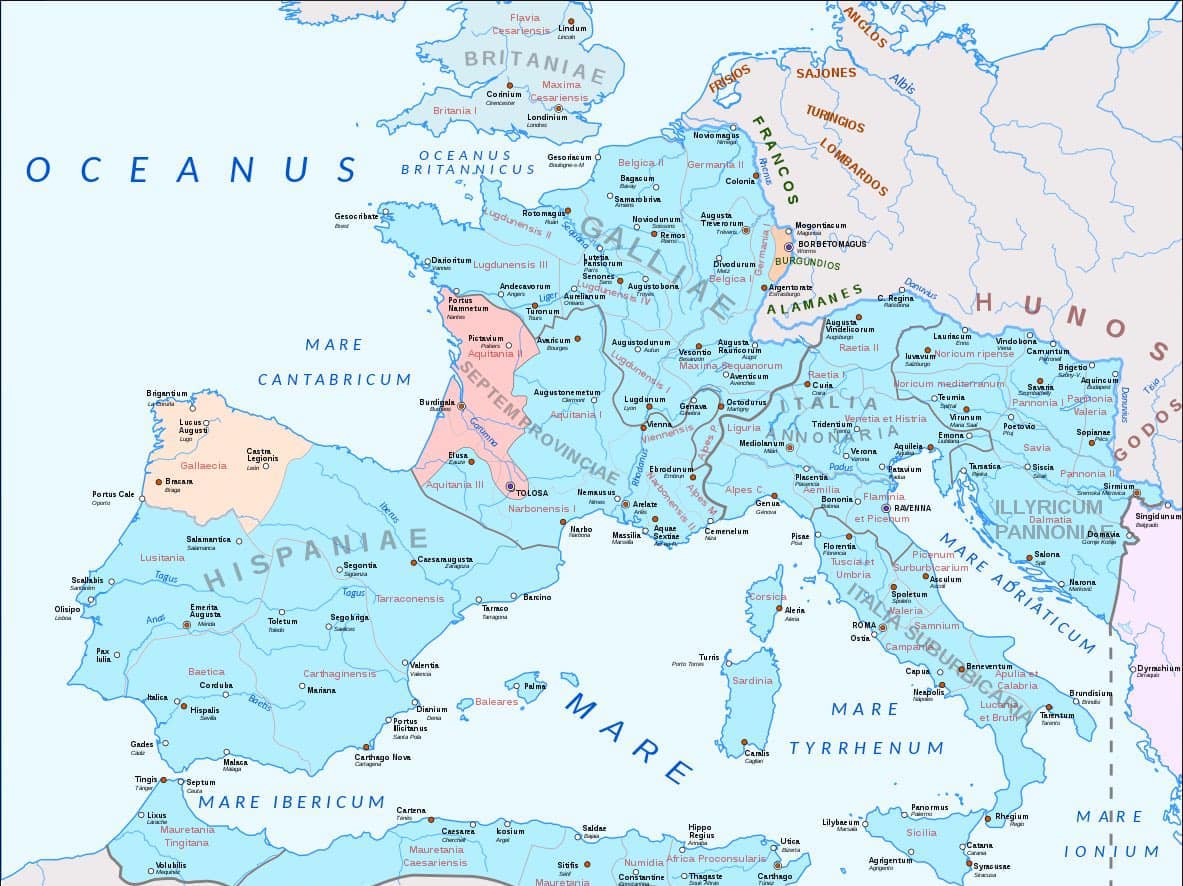

The stalemate was broken when the Greuthungi, the eastern Goths whose cavalry had been so decisive at Adrianople, went their own way in 380, and moved westward into Illyricum—the Roman province made up of plains that now are part of modern Serbia, Croatia, and Hungary. This brought the Goths under the jurisdiction of the Empire’s western Emperor, Gratian. (Technically speaking, Theodosius ruled the entire Roman Empire, being the last Emperor whose authority spanned the Empire’s eastern and western halves. But in practice, jurisdiction had been split since the late third century C.E.)

Gratian was a talented commander, and moved quickly to check this invasion. The Greuthungi were stopped and, whether by way of military defeat or diplomacy, settled in Pannonia, the area north of Illyria and south of the Danube River. Gratian then continued on and gave Rome’s eastern armies’ collective spine a much needed stiffening. A stalemate ensued, and negotiations with the Goths began.

Under the agreement that emerged in 382 C.E., the Goths were brought (nominally) into the Empire, and would serve as foederati in the Roman army. But the agreement was significantly different from those that had been brokered with other groups. Lands between the Balkan Mountains and the Danube River were granted to the Goths, who would farm them as an autonomous community residing on Roman territory. They were allowed to live under their own laws in regard to internal affairs, and were unable to legally join the Imperial community (meaning they could not marry Romans). Their foederati troops were entitled to payment and supply from the Empire, though exactly how much is lost to history.

The Romans acknowledged no specific leaders of the Goths. And so I can’t offer any kind of closure on the careers of the Gothic commanders who originally crossed the Danube—Fritigern, Alatheus, and Safrax. They simply disappear from the record after the end of the 376-82 C.E. Gothic War.

There’s a suggestion that Fritigern may have stepped down, been overthrown, or killed as the price of peace, but that’s complete speculation. And such an outcome would seem inconsistent with his high stature among his people.

In the interest of tying up loose ends, let’s also bring the story of Fritigern’s great rival, Athanaric, to an end as well. As discussed in the last instalment, Fritigern had been a persistent thorn in Athanaric’s side when the two men were vying for power north of the Danube, and physical separation apparently failed to blunt their animosity. After escaping the Huns, Athanaric had slipped across the Carpathians and carved out a small territory for his followers—an area called the Caucaland (which, in the best traditions of confusing Eastern European geography, is nowhere near the Caucasus mountains, but instead may have existed around the headwaters of the Mureš River in the north of modern Romania.

We know basically nothing of Athanaric’s life in exile, except that Fritigern still had contacts in the old kindins’ camp, and plots continued to be hatched. We know this because eventually one of them succeeded. In circumstances that are infuriatingly vague, Athanaric was forced out of his tribal position and showed up unexpectedly in Constantinople in 381 C.E., seeking Imperial sanctuary.

Theodosius met Athanaric in person at the gates, and he was treated as an honored guest of the Emperor. This was before the end of the war, and Theodosius was trying to demonstrate his willingness to forge good relations between Goth and Roman.

But just two weeks later, Athanaric was dead. His demise came as a shock, and some suspected foul play, but there’s no way to really know. The Emperor arranged a splendid funeral for the old enemy. We don’t know how old he was exactly, but I think mid-to-late 50s would be a reasonable guess for the Gothic Vercingetorix.

Another famous Goth whom we’ve discussed at some length, the Bishop Ulfilas, died at about the same time—also passing at Constantinople, and also receiving a magnificent send-off. The founding messenger of Gothic Christianity was about 70 years old, a revered elder of his people.

There’s one more historical actor that we should say goodbye to at this point: the Thervingi. The tribal name had been in use for centuries, with these eastern-originated Goths being seen as distinct from the western-originated Greuthungi. But the term disappears from the sources after 380 C.E. (The last known reference corresponds to the name of a levied unit of foederati soldiers.) The Goths were changing inside the Roman empire, becoming a new people.

Soon, they would take the name vesi—shining, or glorious—and become the Visigoths (though there is some debate and confusion about where the name comes from). “Ostrogoths,” whom we’ll be discussing later, certainly refers to eastern Goths—and that label is usually contrasted with Visigoths as western Goths (though most of the time, they’re referred to in contemporary sources simply as Goths). But neither of these terms correspond to the original categories of Greuthungi and Thervingi.

In any event, I’ll be using Visigoths from this point forward, to indicate Goths inside the Empire; and Ostrogoths to indicate those outside the Empire. The most famous and well-known division between Goths is now in effect.

The Rise of AlaricNew leaders were also emerging—none most famous than the Alaric, a Visigoth descended from the noble Balti dynasty of the Thervingi. History remembers him as Alaric the Bold.

Alaric was born around 365 C.E., supposedly on an island in the Danube delta, though there’s no firm evidence for either of those facts. His status as a Balti descendant (and therefore a member of the second of the great ruling houses of the Goths, the first being the Amals) comes to us from the eastern Roman writer Jordanes. If true, this would make him related to Athanaric. But Jordanes was writing in the sixth century, and there is absolutely no reliable information about Alaric that can be sourced to the period before 391 C.E., when he led an (unsuccessful) invasion of Thrace.

Alaric likely would have been in his early teens when the Thervingi were forced across the Danube and fought the battles that culminated at Adrianople. Which is to say that he would have come of age in the period of fear and hunger that followed the Goths’ displacement by the Huns. He also would have seen first-hand the perfidy and high-handed treatment regularly meted out by the Romans.

He would have been surrounded by veterans of the wars, and been familiar with his people’s capabilities and traditions. An Arian Christian, Alaric contained a little of both worlds in him—a fierce loyalty to his people, but also a clear understanding of the power, wealth, and history of the Roman Empire. The quotes attributed to him are terse and menacing.

The Gothic settlements in which Alaric came of age were operating within a geopolitical system that would not prove sustainable. The agreement of 382 C.E., discussed above, allowed large groups of Gothic settlers to live cheek by jowl among the incumbent Roman inhabitants between the Balkan Mountains and the Danube River. When disputes among the different groups arose, as they inevitably did, the Goths settled matters according to their own customs, as they had always done when the chief or judge (kindins) was far away. The Roman Emperor was now their kindins, and he was, indeed, quite far away.

Theodosius was surprisingly tolerant of Gothic customs, and more or less allowed the Gothic community to get on with it according to traditional ways. Local Roman officials were irritated no end by this arrangement. But the army’s continuing recruitment problem meant that it was not possible to renege on the deal: Gothic manpower had become too valuable to lose. Ultimately, the defense of the Empire depended on good relations between Constantinople and her new subjects.

Those relations held for just under a decade, and their breakdown corresponded to the emergence of Alaric as an important historical figure. The first we hear of him is as leader of a confederation of raiders, mostly Visigoths, but also Sarmatians and Huns, as well as rebellious Roman citizens. In 391 C.E., this confederation set out plundering south of the Balkan mountains into the center of Thrace. The poet Claudian sneered that Alaric was a “little known menace.” But the raiders were threatening enough that Theodosius’ forces were denied freedom of movement through the area, so Claudian was probably sidelining in a role that we would now call spin doctor.

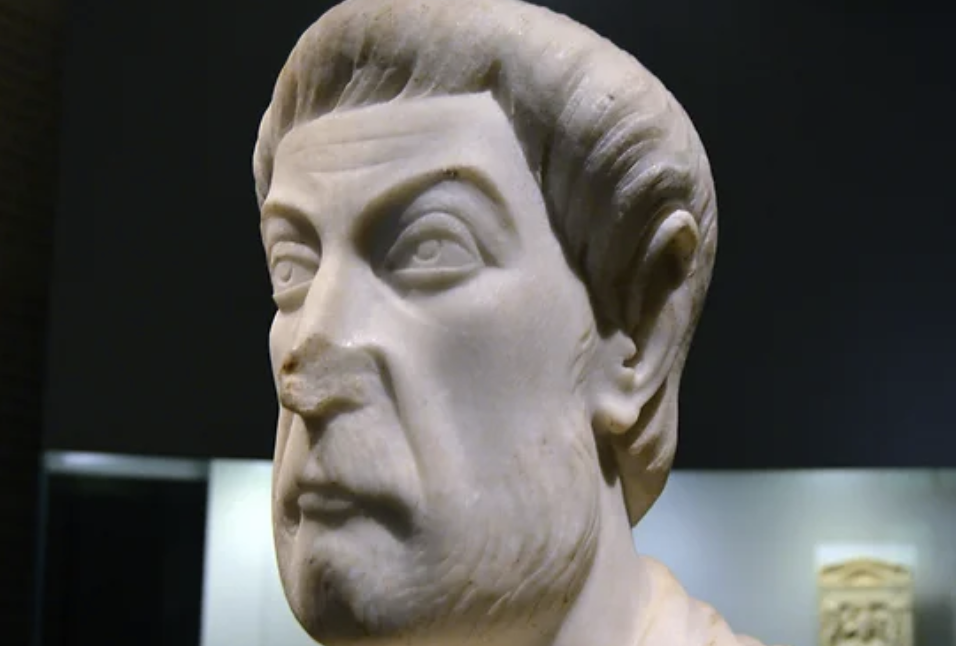

Alaric’s raid of 391 C.E. serves to introduce another character to the story: the Roman commander Stilicho, who was then a trusted general in service of Theodosius. In time, Stilicho would become the most powerful man in the Western Empire, but we’ll leave that fact to one side for now.

The first encounter between there two great leaders was anti-climatic. After maneuvering around Alaric for a while, Stilicho defeated and surrounded his army. And then orders came from the Emperor telling Stilicho to let the Goths go. The Empire could no longer afford to destroy such huge pools of potential federate troops. An agreement was reached, which gave Alaric a position in the Roman military hierarchy. The first agreement—the foedus of 382 C.E.—was also reconfirmed. Nevertheless, the cracks separating Roman and Goth were starting to show.

Alaric’s position was then subordinate to a fellow tribesman named Gainas, a Goth who had been serving the Romans for some time. Despite being only in his early twenties, Alaric apparently felt slighted by this lesser stature, as Gainas was a man of “no lineage.” This kind of personal rivalry often played a significant role in barbarian politics—as we’ve already seen with Athanaric and Fritigern, and Alaric would become involved in several such feuds over the course of his career. But for now, he bit his tongue and got on with his duties, like a good soldier.

Alaric learned a lot in the Imperial service, including some hard truths. In 394 C.E., he was leading Gothic troops in Theodosius’ army against Eugenius, one of the many usurpers who popped up during this late stage of the Roman Empire. At the Battle of The Frigidus, in what is now western Slovenia, Alaric’s Goths were lined up in the vanguard against Eugenius’ Frankish soldiers. When battle commenced, Theodosius’ strategy was to overwhelm the Franks with wave after wave of Goths. Little to no concern was spared for the heavy casualties they endured.

Ten thousand Goths are reported to have been killed. Even allowing for the usual exaggeration exhibited by chroniclers of the period, it’s clear that the battle was devastating to the Gothic forces. Worse, Theodosius seemed to take little notice of Alaric or his men after the battle was won. And there were rumours that the Emperor, along with his native Roman generals, were privately quite pleased that they had both defeated the usurper and thinned the ranks of the Goths. Alaric was left with nothing to show for his service except the knowledge that he and his people would never be treated as anything but second-class citizens and cannon fodder.

But then the situation shifted at the beginning of 395 C.E, when Theodosius suddenly died. He would be remembered as the last Roman Emperor to rule a (technically) united empire single-handed.

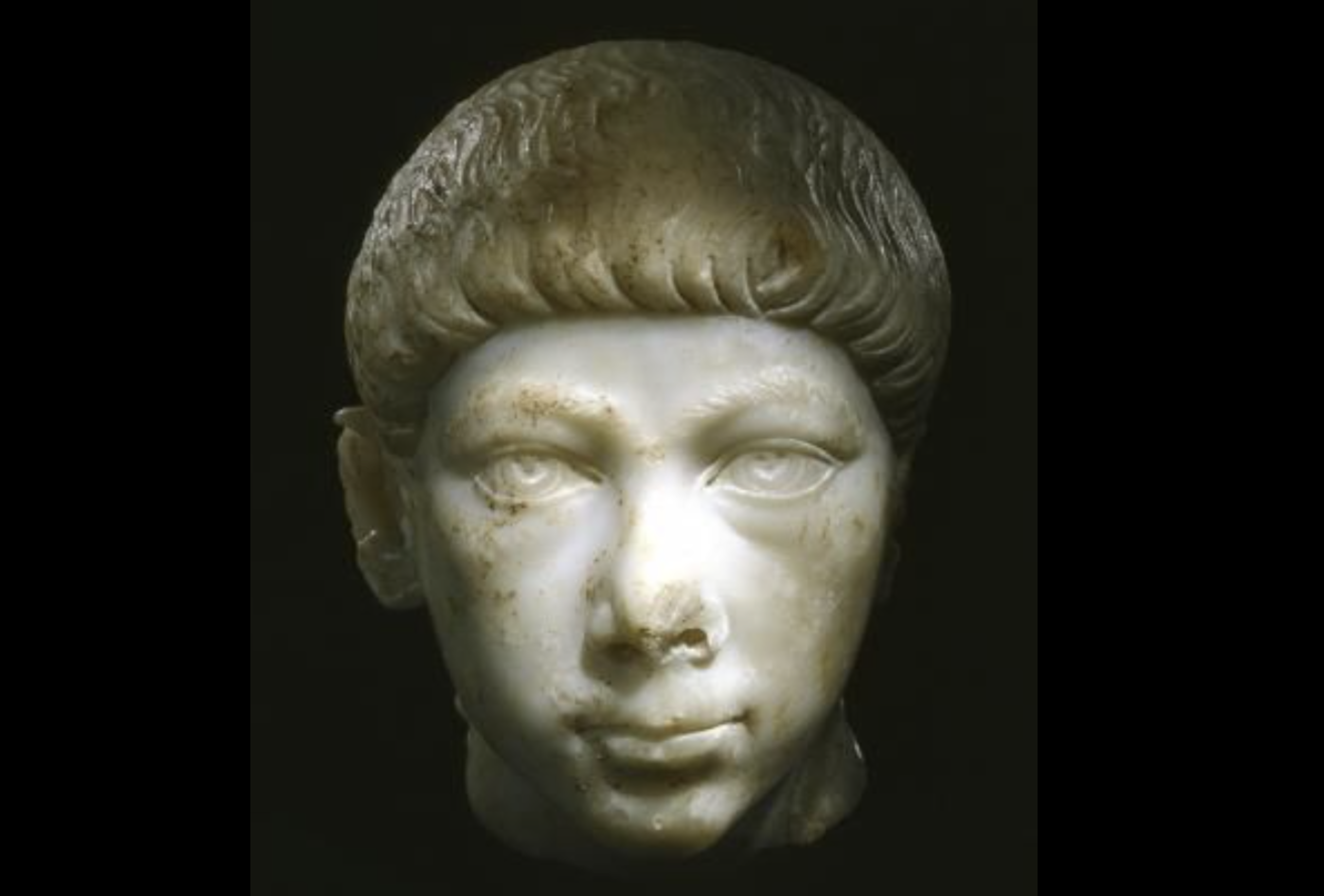

Both of Theodosius’ heirs were still underage at the time of his death. And it was decided that the eastern part of the Empire would go to his elder son Arcadius, who was 17; with the west going to the younger Honorius, then just 10.

Neither of them were the men (of boys) for the jobs, it turned out, in terms of temperament as much as age. Real power fell into the hands of the officers that surrounded them—ambitious soldiers and administrators (such as the aforementioned Stilicho). And this would remain the status quo for the remainder of the life of the western Empire.

Alaric took advantage of the confusion that surrounded this regime change. The original foedus had been rendered void by the death of Theodosius. And outrage had grown when the Roman army failed even to arrange enough supplies for Alaric’s army to return home following its heroic performance in the battle against Eugenius. And so, on the way back from that campaign, Alaric led raids against towns in Illyria that lay along their route.

This put Alaric at odds with the Empire, needless to say. But by this time, Roman leaders had become distracted by large organized Hunnic raids into Imperial territory. Gainas was in command of the Roman response, which meant Alaric (beeing an eastern Roman asset) would not take part. Instead, he returned to the Balkan plains and convinced the Goths still residing in his homeland, which was itself now the target of Hun raiders, to join him in a general rebellion.

In marching his followers toward Constantinople in 395 C.E., Alaric was trying to force the Empire to the negotiating table. His Visigoths wanted new lands, further south, in the valleys of Macedonia, or really anywhere where they could be safe from the Huns.

The man who then held power in Constantinople was Flavius Rufinus (known to history simply as Rufinus), who’d been appointed magister officiorum (“master of officers”) under Theodosius. It seems that Rufinus had a preexisting relationship with the Goths to build on, and there were rumors that his own lands in Thrace had been untouched by plunderers.

Rufinus met with Alaric in person, and quickly granted his Visigoths lands in Illyria and Macedonia. He may have also granted Alaric the title of magister militum per Illyricum—commander of all troops in the Illyria region. Even Alaric must have seemed shocked by how easy that was.

Indeed, it was too easy. What Rufinus had done was what a modern lawn-care enthusiast might apply the “leaf-blower solution”: he transformed his own problem into his neighbor’s problem.

That’s because the lands that he’d oh-so-graciously ceded to Alaric were actually under the jurisdiction of the Empire’s western court. They weren’t his to give away. And the people who lived there resisted the newcomers’ presence fiercely.

Alaric was able to get around the militias that were mobilized to fight him, and took up a position on the Thessalian Plain, south of Mount Olympus, where he set up his wagon fort, in full knowledge that a Roman army would be coming from the west.

Stilicho, now the power behind the throne in the west, was the man leading that army. But when he arrived, his Roman soldiers simply stared at the Goths across the plain, with no battle taking place for several months. This (second) anti-climactic encounter with Alaric ended when Stilicho was forced to withdraw back to Italy, on orders from the eastern Imperial court, which was irritated by the presence of western armies on Arcadius’ territory. By giving in, Stilicho effectively ceded Illyria and Macedonia to the eastern portion of the Roman Empire, a concession he would later come to regret.

Rufinus, Stilicho’s eastern counterpart, tried to protect the Greek communities that were now exposed, but with no success. Alaric forced his way past Thermopylae—yes, that Thermopylae—and began plundering cities. Piraeus fell, and the Goths plundered the great temple at Eleusis. Athens was supposedly saved by the appearance of Athena and Achilles on the city walls, though the massive amount of cash the city forked out to the Goths probably had more to do with its survival. With ridiculous ease, the Visigoths reached the Peloponnese peninsula and looked for all the world as if they meant to stay there.

But then, in the spring of 397 C.E., Stilicho arrived again, this time as part of a joint operation with the eastern armies to handle both Alaric and the Huns. He landed in Greece and began a campaign for position, which he turned out to be vastly better at than Alaric. Within a few months, he had Alaric bottled up on a high, waterless plateau. Alaric must have been cringing in anticipation of the final blow, but it never came. Instead, Stilicho made yet another deal with the Visigothic chief, and withdrew. The Roman commander’s rationale for doing so is debated to this day.

When the eastern contingent that was under Stilicho’s command returned to Constantinople, Rufinus rode out to meet them—at which point he was promptly assassinated by Gainas, Alaric’s old commander. The new new power-behind-the-throne in the east would now be a eunuch named Eutropius, who promptly declared Stilicho a public enemy.

Whatever the nature of this latest agreement that Alaric had reached with Stilicho, the Gothic leader broke it as soon as the western Roman commander’s forces had passed over the horizon. He moved his people into Epirus—roughly corresponding to the southern half of modern Albania, along with portions of Greece. And at this point, Arcadius—this being the name of the young eastern Emperor, if you recall—made yet another foedus with the Visigoths—the fourth since 382 C.E.—making Alaric magister militum of Illyria again.

“Why on earth would he do that?” you might ask. It’s only been six years, but Alaric has already reneged on at least three agreements in that time. It goes to show the desperate straits that the Roman state found itself in at this late stage. It did not have the capacity to exterminate the Goths, or expel them from the Empire; and even if it did, its army would then become critically underpowered and so unable to keep the many other threats at bay.

Remember, too, that the Goths were the most Romanized of the major barbarian groups, and so striking agreements with them was still seen as the least bad option available. That fact made Alaric’s position much stronger than might otherwise appear.

At this point, we can start to refer to Alaric as King of the Visigoths. He now was the only recognized leader of the Gothic peoples within the Empire, and held a position in the Imperial Roman bureaucracy. This was a new development for the Goths. In the course of the previous decade or so, their leadership had shifted to combine the traditional roles of reiks and kindins in the single figure of king.

With Rufinus dead and Stilicho expelled from eastern lands, Alaric seemed to be on his way to achieving his major goals, having been granted military title to Illyria, along with gold and grain subsidies for his people.

But things changed quickly when another palace coup rocked Constantinople, pushing Eutropius out of power (and eventually into the grave). Gainas, Alaric’s old Gothic rival (and Eutropius’ former ally), became magister militum, and promptly transferred control of Illyria to Stilicho, while stripping Alaric of his title and repudiating the deal made by Eutropius. New management, new rules, as the expression goes.

The Goths Invade Italy (Part I)Unable to challenge the ascendant Gainas for the moment, Alaric turned west. He may have been encouraged in this move by news from the north, as a combined force of Alans and Vandals were then invading the provinces of Noricum and Raetia, on the northern side of the Alps. This had drawn Stilicho and his army away from the Italian heartland, allowing Alaric to pounce.

His first attacks on northern Italy began in 402 C.E, or maybe late 401 C.E. Probably driven mostly by the need for provisions, the Visigoths crossed the Alps near the ancient coastal fortress city of Aquileia (now situated on Italy’s northeastern border with Slovenia), but passed it by, and attacked smaller towns as well as traffic along the roads.

Alaric’s ambition was not limited to stolen produce though. He wanted a new deal, and he worked his way across northern Italy, aiming to force the Empire to offer him one. For somewhere between six and nine months, Alaric’s army had its way with the settlements of northern Italy. He even laid siege to the Roman capital at Milan. But by then, Stilicho had managed to extract himself from his northern entanglements and marched back into Italy, fuming.

Alaric tried to maneuver to avoid Stilicho, but the Roman army caught up to him, and they fought two battles, the first and larger at Pollentia, in what is now Piedmont, and the second at Verona. At Pollentia, we are told, Stilicho took a large number of prisoners, including Alaric’s wife, and recaptured most of the treasure the Visigoths had taken. Verona was another crushing defeat, and Alaric was forced to withdraw from Italy altogether.

This certainly seems like a win for Stilicho. But as the legendary historian J.B. Bury pointed out, it actually undermined his status.

Yes, he had driven the Visigoths off, but he had been unable to prevent them from entering the Imperial heartland in the first place, and they had been free to pillage and burn across northern Italy for nine months before Stilicho had mustered an adequate response. He was supposed to be the supreme military commander; that meant that he was supposed to be protecting the security of the Empire. In the eyes of his rivals at court, most of whom were members of the landowning nobility whose farms had been ravaged, Stilicho had failed.

The invasion also prompted the transfer of the Imperial residence from Milan to Ravenna on Italy’s eastern coast. The new location was easy to defend, as it was protected by swamps. But what kind of look was that for an Imperial capital?

On top of that, in spite of beating the Visigoths twice, quite convincingly it seems, Stilicho had allowed Alaric to leave Italy, and had even offered to return prisoners in an exchange that Alaric turned down. Stilicho did not destroy this clearly destabilizing force that had wreaked so much havoc on the home country. Why? What was Stilicho up to?

What he was up to was a cold war against the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Stilicho was clearly a man of towering ego and ambition. And after Theodosius had died, it was obvious to Stilicho that he should be the man who shepherded the man’s young sons through the difficult early years of their reigns—both of them (or, by another interpretation: take advantage of the youth and general weakness of the Emperors, so as to set himself up as the de facto dictator of the entire Roman Empire). In Alaric, Stilicho recognized a potentially useful tool.

For Alaric’s part, the issue was the same as it had always been. The great raid had kept his Goths fed. But if he didn’t find a place for his people within the Roman Empire, with dignity and a stable livelihood, they would find themselves a new king. Several subordinate commanders had already taken the opportunity to defect to the Romans, in fact (including one named Sarus, who would have a key role in later events). So a deal with Stilicho in 402 C.E. would have been eminently practical from Alaric’s point of view (though we have only intimation and rumours that any deal had in fact been made at this point).

Stilicho’s other schemes included a plan to bring Illyria back into the west’s orbit. And in 405 C.E., he even prevailed upon the Emperor to name Alaric as magister militum there again. But his plans were upset, first in 405 C.E. by an invasion of Ostrogoths across the Danube; and then again in 407 C.E., by the total collapse of Rome’s Rhine frontier.

Yep, you read that right: total collapse. It’s a development that gets us into the Huns, Vandals, Alans, Suevi, and other apparently unstoppable groups pouring into Gaul. But this series is on the Goths. We’ll have other opportunities to explore these other groups in future arcs.

For our purposes now, the important thing is that Stilicho was forced to make peace with the east so he could race north. This meant that Alaric was suddenly unnecessary. The Romans broke the agreement they’d made in 405 C.E., and left the Visigoths high and dry, once again without a dependable source of land and food.

In the spring of 408 C.E., Alaric took his men and marched them west again. He parked himself in the highlands of what is now Slovenia, and demanded a payment of 4,000 pounds of gold—or he would invade Italy, again.

And this time, as we shall see in our next instalment, things would turn out quite differently.