Politics

The Chinese Exodus

Fears of a CCP sponsored invasion at the Mexican border are misplaced. People are fleeing China because its economy is in dire straits.

Fears are growing about the large influx of Chinese migrants entering the United States from the south. Video footage shows mainlanders swimming the Rio Grande, crowding at checkpoints, and lining up on a windy night to present documents to border protection officials. Sunbathers on Floridian beaches stare as Chinese men and women emerge dripping from the surf, laden with luggage. But most activity is to be found along the US-Mexico border, where some 13,000 mainland Chinese were apprehended between October and June—a startling increase of 1,000 percent on the previous year. Their route, it seems, is always the same. First they fly into Venezuela and El Salvador, then they trek up through the marshlands and rainforests of Panama’s Darién Gap to the Texan border. There they request asylum, go through “processing,” and disappear into the United States.

Those who post these videos on Twitter have no doubt as to what it all means: “Majority are single, military age men sporting military style haircuts. … Why is the Biden regime allowing an invasion from our adversaries?” They see great significance in the migration route, given that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) already carries out bilateral military activities in Venezuela. The Chinese army, it would seem, is already inside the gates of Troy.

Is this really a stealth invasion? There are many reasons the Party might want to infiltrate American society with sleeper agents. They could speed the great American decline in which Beijing believes so fervently (and mistakenly: the evidence suggests US hegemony will persist this century). They could join riots, commit crimes, incite violence, establish cells. They could bolster the Party’s espionage project—just this month, CCP spies were rooted out in the US Navy. Sleeper agents could carry out targeted assassinations of key personnel (something that the CCP already seems to be planning in Taiwan as a prelude to takeover).

Proponents of the invasion theory sound both mystified and certain: a jarring mix that undermines their position. “We have no idea who these people are,” said Mark Green, House Homeland Security Committee Chairman, before revealing that he has a pretty good idea. “It’s very likely, using Russia’s template of sending military personnel into Ukraine, China is doing the same in the United States.” Many of these interlopers, he went on to say, have “known ties to the PLA.” It’s hard not to suspect political point-scoring. Sure enough, Biden’s name is repeatedly and contemptuously evoked in the threads highlighting this “invasion.”

What are the criteria, one wonders, for distinguishing between a covert military operation and an entirely predictable rise in migrant/refugee numbers? After all, now is exactly the time we would expect to see a mass exodus from the Middle Kingdom. Chinese society has just emerged from three years of zero-COVID stasis—three long, dark, claustrophobic years of snap lockdowns and mass testing. Post-opening, China’s economy is in a terrible state. Foreign direct investment fell to $20 billion in the first quarter of 2023 (it was five times that figure in the corresponding quarter of 2022, even amid the chaos and uncertainty of the zero-COVID era). Youth unemployment in urban areas rose to a record high of 21.3 percent earlier this summer, before red-faced authorities simply stopped publishing the data. That was just the cities—the unemployment situation in the country’s vast interior remains a mystery.

Lockdowns decimated small- and medium-sized businesses. As for the giants, two-thirds of China’s top 100 companies have now lowered their graduate recruitment quotas. Huawei has virtually stopped hiring; Alibaba cut 15,000 jobs last year. Local governments face bankruptcy. And now China has entered deflation. Falling prices threaten to exacerbate everything, depressing confidence that was already depressed, discouraging investment that was already faltering, bringing unemployment to a society already crippled by unemployment.

As if the future wasn’t bleak enough, there is the additional factor of the Communist Party’s incompetence and its catastrophic impact on ordinary lives. We saw this after Typhoon Doksuri, back in July. Record flooding prompted authorities to divert reservoir overflow into heavily populated areas throughout the surrounding Hebei province—an attempt to keep rising waters from Beijing. Normally, spillways would direct floodwater into a crucial expanse of low-lying land just outside the capital. But that expanse is being transformed into a brand new city: Xiong’an. Yet another of the President’s pet projects—his ill-conceived fancies—Xiong’an must be protected at all costs. And so the water was redirected, and soon became the problem of the unfortunate residents of Hebei (they would provide “a moat for the capital,” in the airy assessment of provincial Party secretary Ni Yuefeng). The resulting death toll is still unknown.

As the country’s citizens look to their future, they see unemployment, isolation, declining living standards, and worse—the ever-present black swan element that is China’s modern-day Emperor, virtually guaranteed to keep interrupting their lives in random and disastrous ways. A citizen may live a quiet life, staying out of trouble, toeing the Party line on religion and politics, bribing all the right people at the right moments. It makes no difference, as the lockdown years proved. No one is safe. The main thought in many people’s minds will surely be: “How do I get the hell out of here?”

Those Chinese migrant apprehensions along the Mexican border began their radical rise in numbers around April 2022. It can be no coincidence that April 2022 was also the first month of the now-legendary Shanghai lockdown, when millions of pampered urbanites found themselves facing starvation—that dreaded ghost from China’s past, something they never expected to see, now risen from the history books and looking right back at them with hollow eyes. It was exactly the time, in other words, that people would be most likely to start seeking a means of escape.

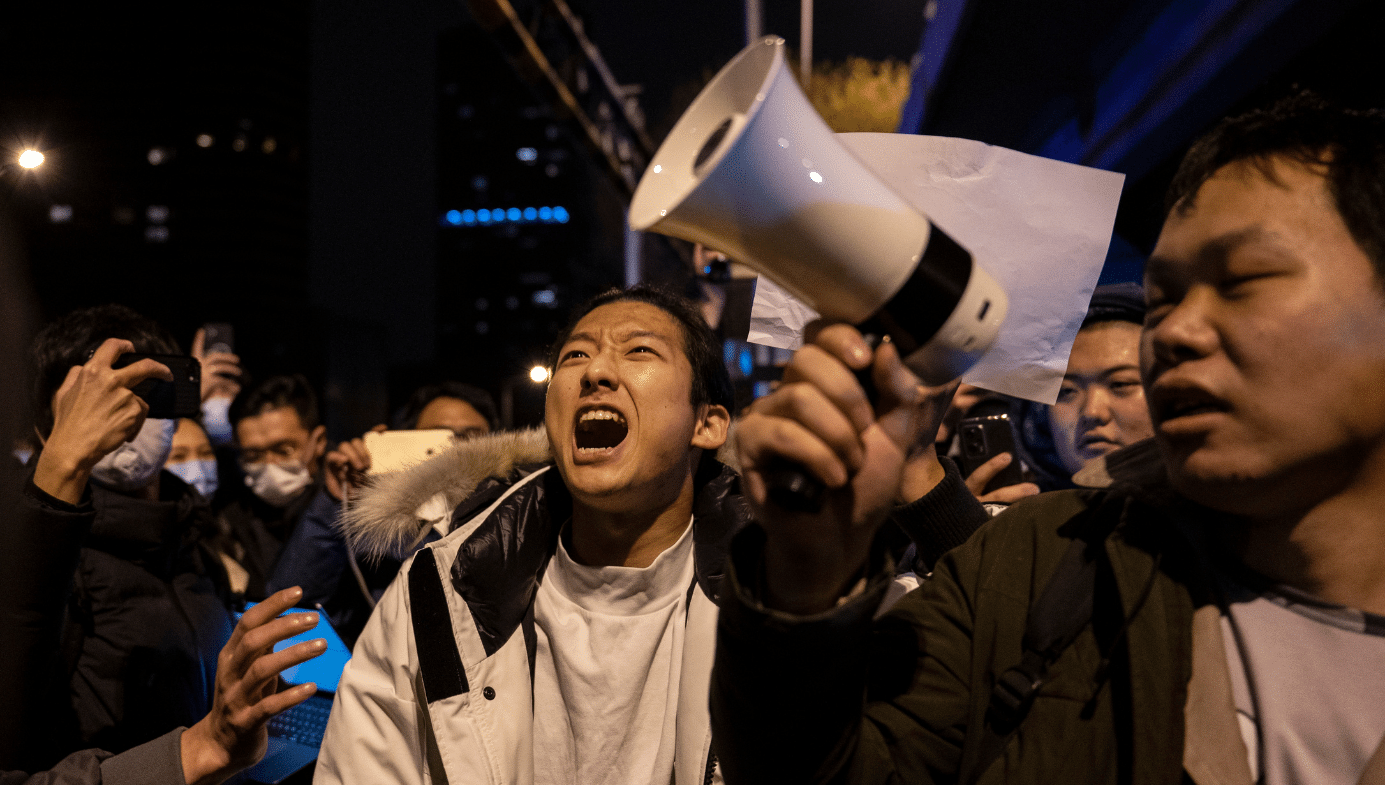

As for “single, military age men sporting military style haircuts,” most of the men depicted may be young, but first glance does not suggest military-grade. And those incriminating military-style haircuts are actually far more common among ordinary mainland Chinese than their American counterparts, due to the homogenising, collectivist culture inculcated by the Communist Party—a culture that seeks to break down all expressions of individuality. Single men of fighting age also happen to be the very demographic that has always ventured abroad, from all countries, in search of a better life. Money is sent back home to families, and those families may follow the breadmaker’s path after some years. Within China, unnoticed by these angry American commentators, huge numbers of “single, military age men sporting military style haircuts” spill into the major cities every year, looking for the work they can’t find in the rural provinces of their origin.

We even have detailed stories from some of the Chinese who undertook the great Latin American odyssey. Daniel Huang was struggling to find work, and also facing the threat of jail time after participating in protests over contracts, so he decided to make a run for it. First, he obtained a passport after paying for a fake overseas college acceptance letter. Then he obtained a visa after convincing Chinese border officials that he needed to go to Turkey to survey restaurants. Safely out of China, he flew to Istanbul and on to Ecuador, where he paid smugglers to drive him over the Colombian border before sailing him to the edge of the Darién Gap—one of the most inhospitable places on the planet, and the most dangerous of all migrant routes.

Once inside, there are no roads. The Gap is 66 miles long. Travellers must wade through swamp and hack through jungle, keeping an eye out all the time for Brazilian wandering spiders, fer-de-lance pit vipers, scorpions, jaguars, and the poison dart frogs that have traditionally provided certain tribes with the toxins for lethal blowdarts. Unexploded bombs lurk beneath the mud like another deadly species—the legacy of US military training runs during the Cold War. Sometimes gunshots echo under the forest canopy, indicating the presence of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). They position themselves along the trail and rob migrants. The jungle seethes with parasites, and most people fall sick sooner or later. For some of them it becomes impossible to go on. Huang realised the fetid stench hanging over the trail was likely caused by unburied corpses in the undergrowth.

Things hardly improved once out of the jungle and back to civilisation in Mexico. To avoid the police, Huang and three other Chinese ended up traversing Mexican Federal Highway 101 on two motorcycles. Commonly referred to as the “Highway of Death,” this is 300 miles of road patrolled by gangsters who hijack buses and cars to carry out random rapes, decapitations, and forced gladiatorial contests in search of new cartel recruits. Sure enough, just outside La Coma, the migrants found themselves pursued by a van full of men waving guns and shouting “Chino, Chino!” Huang made it to the nearest military checkpoint, but the second motorcycle was caught. One occupant escaped by crawling under a fence, inches from death, banditos clawing at his feet and taking his shoes. His companion was hauled into their van, where he had the lifesaving idea to fake a heart attack. He was found much later by soldiers, lying at the roadside in a state of severe dehydration.

Some 60 days after leaving China, Daniel Huang finally scaled the border wall into Texas, where he began the process of asylum application. Is this extraordinary two-month ordeal really the means by which Beijing sneaks government operatives into the country? Even the most passionate of scaremongers must concede the oddness of the method. Those invasion reports begin to feel like an insult when we think of China’s desperate escapees, out there at night in seas and swamps and mountain passes, risking it all as they climb through the Isthmus of Panama to the long ribbon that links North and South America—the dangling lifeline to the land of the free.

“Another company of military-aged men headed for the United States,” fumes a recent Muckraker post. In the accompanying video, a camera ranges over long queues of men, women, and children at the San Vicente migrant camp in Panama. Several men turn their heads so that their faces will not be captured. Perhaps that is what a sleeper agent would do. Perhaps it is what a drug mule would do, with fentanyl precursors concealed about his person. It’s also what you might do if you were a normal Chinese citizen making your first nervous foray into a foreign land. Paranoid enough after growing up in totalitarian China, with its perpetual sea of cameras, your paranoia would only increase when planning a long-term hazardous escape for your family. And now complete strangers are filming your face, barking at you: “China? China?”

Unfortunately, the treatment of Chinese may be about to worsen in many parts of the world. Beijing’s economic folly is to blame. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) saw a trillion dollars given in loans to 150 countries, with repayment due in the latter half of the 2020s. Many of these countries are unstable, still developing. The loans will not be repaid. By the Communist Party’s own estimates, it stands to lose 80 percent of its money in Pakistan, 50 percent in Myanmar, and 30 percent across Central Asia. This leaves Beijing with two options. It can simply write off hundreds of billions of dollars in losses. Or it can begin seizing assets in debtor states, many of which are struggling to feed their own people.

We’ve already seen where this leads, as the scholars Hal Brands and Michael Beckley remind us in their book Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China. In 2017, Sri Lanka defaulted on BRI loans:

Charges of “debt-trap diplomacy” reverberated from New Delhi to Tokyo to Washington, droves of countries dropped out of BRI or demanded to renegotiate their contracts, and anti-China political parties swept into power in several partner nations. Meanwhile, Chinese citizens wondered aloud why their government was investing, and losing, billions overseas when more than half of China’s population still lived on less than $10 per day.

That same narrative could play out time and again over the coming years. The BRI has already sparked protests in Malaysia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Cambodia, and Zambia, as angry locals protest colonisation, corruption, pollution, lost property, lost income, damage to livelihoods, and so on. These protests have led in some cases to the hasty cancellation of infrastructure projects. In Pakistan earlier this month, longstanding anti-BRI protests escalated when a convoy of Chinese engineers was attacked en route to the deep-water port at Gwadar (a Belt and Road project). The assailants detonated a roadside bomb, and then opened fire on the vehicles.

Anti-China sentiment is on the rise. As the Chinese economy continues its steady decline and Beijing loses the protective shield of its long-formidable financial clout, the cynics and the hypocrites will suddenly find that they have a million and one reasons to hate China—starting, of course, with the multiple genocides committed by the Communist Party.

If a desperate Beijing begins seizing assets across Asia and Africa later this decade, then the anger will reach a deadly new apogee. We might hope that such anger would be directed solely at the murderous brutes who lead the Party. Sadly, this is probably expecting too much from most people. The distinction between regime and nation has been hopelessly muddied by the CCP’s own overseas propaganda. And it’s just easier to identify phenotypic markers than political affiliations.

Perhaps there was a harbinger of the future in those keen cameras scanning the lines at San Vicente, hunting for the giveaway features. “China? China?” This is not to say that any of those journalists were Sinophobes. But the scene is one that may repeat itself in a darker context, especially as the situation worsens and the great Chinese exodus increases. If large-scale race hatred is looming on our horizon, then we need a solution.

A wish to avoid Sinophobia does not require us to be incautious. Chinese spies are real and numerous. Those with proven connections to the PLA—or even the CCP—have no place in the United States or in any other Western country. But these people are not likely to be found queueing at the Mexican border after navigating the horrors of the Darién Gap. They find other points of ingress.