Nations of Canada

Frobisher’s Failed Arctic Gambit

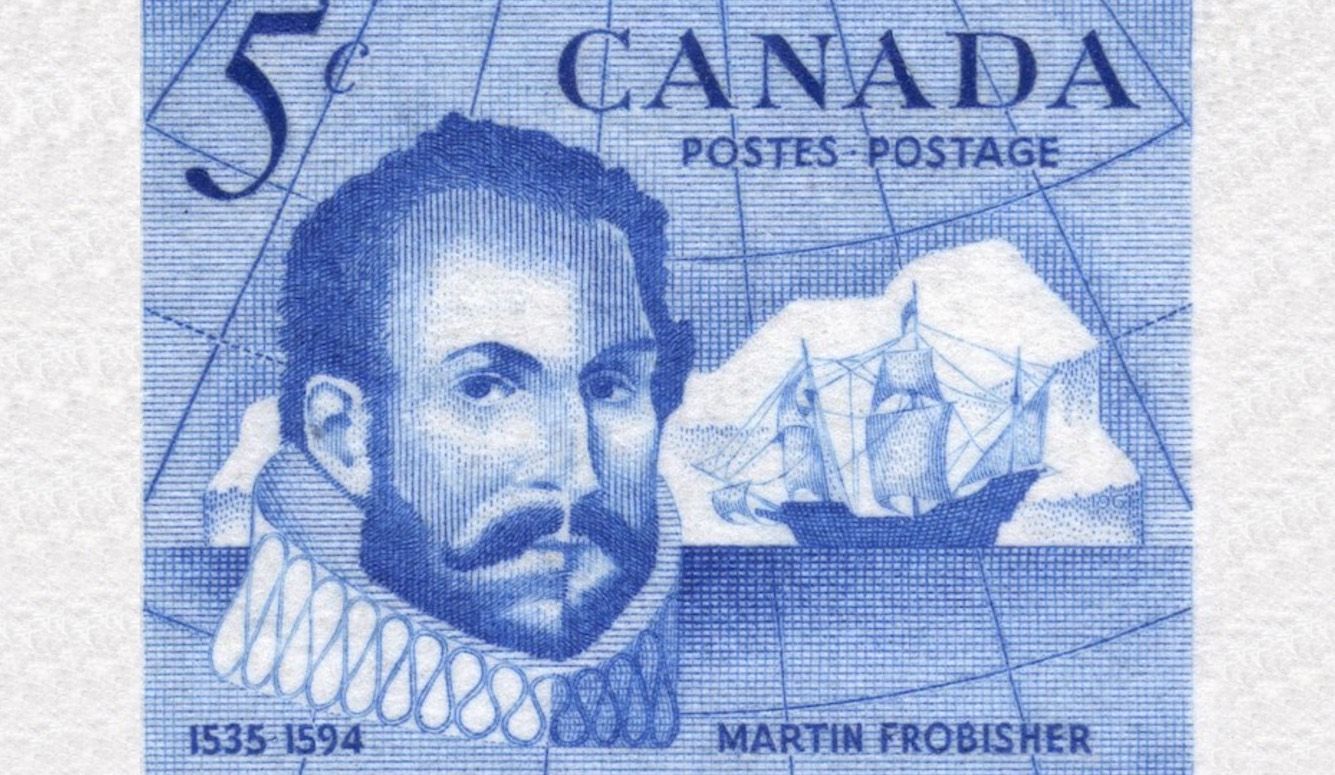

In the eighth instalment of an ongoing Quillette series on the history of Canada, Greg Koabel describes the legacy of Martin Frobisher, a brave explorer who antagonized the Inuit while harvesting worthless minerals

What follows is the eighth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialized project adapted from transcripts of Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name, which began airing in 2020.

Our story this time around is, in many ways, a repeat of Jacques Cartier’s voyages of the 1530s and 1540s—but taking place several decades later, in a different part of Canada, with a very different cast of characters. There was the same initial sense of promise, the same enthusiasm for the project back home, leading to a similar colonization effort—followed by a similar feeling of disappointment.

The goal, as was originally the case with Cartier, was finding a path to the Orient. But where the French had sought a middle passage, the English (our protagonists this time) hoped for a northern one.

Geography had quite a lot to do with this. Perched off the northwestern edge of Europe, England was ideally positioned to exploit a northern passage around the Americas. If the route existed, it was likely to be far more direct than Spain’s long detour around South America, or Portugal’s African route.

By this time, in fact, the English had already begun probing the Canadian arctic. It’s possible that William Weston (who was John Cabot’s partner in the port city of Bristol, as discussed in the fourth instalment of this series) had led a voyage in search of a path through the ice in 1499 or 1500, during the reign of Henry VII. Cabot’s son, Sebastian, subsequently tested those waters in 1508/1509. But by the time he returned to England, Henry VIII had come to the throne, and the English Crown lost interest in further exploration.

We don’t know the details of either Weston or Sebastian Cabot’s voyages, but it’s likely that what they found did little to inspire much enthusiasm anyway. The veterans of the Newfoundland fisheries had quickly learned that venturing north along the Labrador coast was unpleasant to say the least. Storms were frequent, and even in summer, floating ice presented a constant danger.

In the 1520s, the merchants of Bristol (backed by Henry VIII’s top advisor, Cardinal Wolsey) had organized another voyage. But its captain, John Rut, took one look at the ice floes north of Newfoundland, and decided the French had the right idea by avoiding this area. The only sane passage was one through North America, not around it. As England could not compete with French and Spanish power in these waters, the project went no further.

For the next fifty years, the English presence in North American waters was mostly limited to the Newfoundland fisheries. Ships from Bristol joined their French and Basque counterparts from St. Malo, La Rochelle, St. Jean du Luz, and San Sebastian in a free-for-all competition for resources.

Things began to change only in the second half of the 16th century. As has often been the case so far in our narrative, the driving force was European politics. Specifically, the emergence of England as a firmly Protestant state after a period of religious turmoil. After suffering through the whiplash of the radical Protestant regime of Edward VI, and the equally robust Catholic regime of Queen Mary, England finally achieved some stability in 1558 with the arrival of Queen Elizabeth on the throne.

The diplomatic implications of Elizabeth’s Protestant reign would take some time to emerge. But, in the interest of brevity, I’ll over-simplify matters by singling out Elizabeth’s rivalry with the ultra-Catholic King Philip II of Spain (who’d been married to Elizabeth’s half-sister, the late Queen Mary). Things wouldn’t truly come to a head until the Spanish Armada of 1588. But in the meantime, Anglo-Spanish religious and dynastic tensions were unwelcome news for England’s merchant community. England’s exports mostly consisted of wool and unprocessed cloth, which were sent to the textile factories of the Spanish-controlled Netherlands. The constant threat of war meant uncertainty for many businessmen.

It didn’t help that many of King Philip’s subjects in the Netherlands were themselves Protestant. Even if England didn’t get involved in a Spanish war, religious rebellion was likely to throw the whole region into turmoil. (And, indeed, the Netherlands did erupt in rebellion in the late 1560s, leading to what we now call the Eighty Years’ War.)

Early in Elizabeth’s reign there was, therefore, a movement to diversify England’s international trade profile. Merchants started looking for new markets—including an especially prominent trader named John Yorke. Commerce was the family business, and as a young man in the 1520s and 1530s, Yorke had acted as the family’s agent in Antwerp (the main destination for English cloth exports). While on the continent, Yorke also served in the informal spy network of Thomas Cromwell (who was then Henry VIII’s right-hand man).

In effect, Yorke was getting an apprenticeship in commerce, politics, and diplomacy. His graduation came during the chaos that followed the death of Henry VIII in 1547. Again, the ins and outs of Tudor politics aren’t our concern here. So suffice it to say that Yorke was a major player in the regencies that ruled in the name of Henry’s successor, the child-king Edward VI. Yorke’s financial acumen won him the post of Master of the Mint—an appointment he used to engineer some shady currency devaluations. Yorke also demonstrated his political instincts in 1549, by abandoning the Lord Protector (and head of the regency council), the Duke of Somerset, just before his political ruin. The new man running the show, the Duke of Northumberland, gratefully accepted this useful defection. And Yorke now had friends in high places to help him pursue his goal of diversifying England’s trade.

In 1552, an opportunity arose. An experienced Portuguese pilot had become disgruntled with his employers and offered his services to England. This man had sailed to the alluringly named Gold Coast of Africa multiple times, something no Englishmen had yet done. Until now, West African navigational charts had been closely guarded Portuguese state secrets. If Yorke funded a ship and a crew, there were immense profits to be had.

Danger surrounded the voyage from the outset. In fact, the expedition very nearly didn’t happen. There was a Portuguese attempt to kidnap the defector, and then, just as the ships were about to set out in the summer of 1553, the 15-year-old King Edward suddenly died, unleashing another round of political turmoil. This time, Yorke was caught on the wrong side of history. His patron, the Duke of Northumberland, was executed as a traitor by the new regime (headed by Edward’s half-sister, and the new Queen, Mary). Yorke himself was thrown in the Tower. But he could console himself with the fact that (amid the chaos) his African voyage had already put out to sea.

The reason we’re starting this story of arctic exploration with a trip to Africa is that our main character was one of the crew—an 18-year-old apprentice named Martin Frobisher. Frobisher was Yorke’s nephew, and also his ward after being orphaned at a young age. Just as Yorke had cut his teeth running things in Antwerp, the plan was for Frobisher to gain valuable experience and contacts in Africa so that he could take his place in the family business. It was hoped that this would be just the first of many successful commercial voyages.

Frobisher and his colleagues soon arrived at Mina, on the coast of modern-day Ghana. The locals there were an important source of gold for Portuguese traders, and they seemed to welcome the opportunity to break Portugal’s monopoly and get the European powers competing with one another. This was exactly what Yorke had hoped for.

But the Portuguese defector on the voyage issued a warning. Due to the delays in setting out, they were traveling in the thick of summer. He advised against continuing along the coast to Benin, to take on pepper, as per the original plan. The ships would be running pretty much along the equator, and prolonged exposure to the summer heat wreaked havoc on European bodies.

But the English were eager to earn greater profits, and decided to push on to the east.

The result was catastrophic. Benin did provide the traders with plenty of pepper, but also a contagious disease. Whatever malady hit the expedition, it must have come on suddenly, because several members of the crew were left on shore in the rush to get away. A ship was abandoned in Mina’s harbour, as well: There simply weren’t enough men left to man it.

Of the 140 men who set out from England, only 40 made it home. Even worse, one of the fatalities was the Portuguese pilot. He was the only one who knew the currents that swept ships out into the Atlantic and sped them home. Without him, the English hugged the coast all the way home, adding weeks to their trip, and costing more lives.

The ships limped back into port in June 1554, a full 10 months after their departure.

One might think that a voyage that lost more than two thirds of its crew would be seen as an unmitigated failure. But men such as John Yorke measured success and failure in profits, not lives. Despite the loss of a ship, the enterprise was a huge financial success. The gold and pepper that the survivors brought back to England were valuable commodities.

More importantly for our story, one of the 40 survivors was young Martin Frobisher.

Yorke was able to count up his profits because while the ships had been at sea, he had won his freedom from the Tower. Once the new Marian regime was secure in power, he was no longer seen as a threat. Yorke was a money man, after all, not a political heavy weight. And with his political career now in ruins, Yorke was able to devote his full energies to his budding African project. In this, he was joined by a new partner, Thomas Lok (a name worth remembering as the story moves forward).

In November 1554, just a few months after Frobisher got home, he was roped into another African voyage organized by Yorke and Lok. Surviving the previous expedition was all the qualification Frobisher needed for the job of African agent. This new voyage was commanded by Lok’s brother, John. It was hoped that the winter months would be kinder to the crew’s English constitutions.

This time, the ships landed at Shamma, the port of another of Portugal’s trading allies on the West African coast (located in modern-day Liberia). Once again, the locals welcomed the chance to play European traders off of one another. Portugal’s monopoly provided tremendous leverage in setting prices.

However, fear of Portuguese military power caused the political leaders at Shamma to be cautious. In order to show good faith, and speed negotiations, Captain Lok offered up a hostage until the commercial transactions were completed. In selecting a candidate, Lok went with Martin Frobisher, the young apprentice who didn’t seem particularly essential to the operation of the ships.

Unfortunately for Frobisher, a well-armed Portuguese fleet arrived before a final deal could be struck. Thomas Lok made for the open sea, writing off the loss of the teenaged Frobisher as the cost of doing business.

Lok was more successful at a few other African ports of call, and the voyage was even more successful than the first one. This time, only 24 sailors failed to return home (including poor Frobisher). If Yorke mourned the loss of his nephew, he hid it well.

Besides, as it turned out, Frobisher wasn’t dead: he had merely been left behind. And he was a resourceful young man, capable of looking out for himself. He spent nine months in the custody of Portuguese traders at Mina. He was technically a prisoner, but the Portuguese permanently stationed in West Africa saw their own predicament as something akin to a prison sentence, and so they had some sympathy for their English inmate. Frobisher endeared himself to his jailers by going on supply runs into the countryside—something the Portuguese viewed as a suicide mission.

By the time a ship finally arrived to take him to Lisbon, Frobisher was quite comfortable.

What happened next is somewhat muddled by Frobisher’s subsequent self-mythologizing. He would later claim that while in prison in Lisbon he shared a cell with a disgraced Portuguese explorer who had attempted to find the Northwest Passage around North America. The attempt had failed, but this prisoner claimed it was possible. In fact, he had seen open ocean to the west, but his ships had been unable to penetrate the ice.

For the moment, this information was of no use to Frobisher, stuck as he was in a prison cell. Eventually, though the Portuguese simply released him. They had been hoping to ransom him to the English, but no one (not even his uncle John) seemed to place much value on the young captive. Seeing that they were not going to get any money for him, the Portuguese didn’t see why they should continue to provide him with room and board, and so shipped him back to England.

Frobisher did not renew his professional relationship with his uncle. In fact, there’s no evidence that Yorke ever paid him the wages he was due for his work on the previous voyage.

Left to find his own way, Frobisher branched out into a new profession. His skills (which essentially consisted of a knowledge of West Africa, and a proven ability to not die in the tropics) were well suited to a job in the exciting world of piracy. In 1559, his name appeared among those involved in a planned raid on Mina, which was discovered and broken up by agents of the new Queen, Elizabeth I.

But while Queen Elizabeth did not want any of her renegade subjects causing a diplomatic incident with the Portuguese, she did have uses for men of the likes that Frobisher was now involved with. Anti-Portuguese piracy on the high seas was one way for Elizabeth to exert diplomatic pressure without getting her hands dirty—so long as the English sea dogs didn’t go totally rogue.

Through the 1560s, Frobisher danced on that line between useful asset and diplomatic liability. Sometimes Frobisher’s voyages had the unofficial blessing of the English Crown, and sometimes they did not. More than once, Frobisher, already a connoisseur of prison cells on two continents, got a chance to see the inside of an English one, too.

For the time being, though we’ll leave Martin Frobisher, adventurer on the margins of the law, on the backburner, so that we might digress into European political developments that will prove germane to our wider narrative.

In 1568, Dutch Protestants revolted against their Catholic King, the aforementioned Philip II of Spain. The Low Countries were split in two—the northeast (comprising roughly the modern state of the Netherlands) was held by the rebel Dutch, while the Catholic south (modern-day Belgium) remained in Spanish hands. This was the scenario that English cloth merchants had feared. While England remained officially neutral (at least initially), the flow of trade was still severely interrupted. The Dutch blockaded Spanish-held Antwerp—a city that for generations had been England’s point of access to the continental market. And the impulse to diversify English trade developed a sudden urgency.

It’s helpful to focus on one merchant in particular—Michael Lok. This was the younger brother of the Thomas Lok who’d partnered with John Yorke to fund those voyages to West Africa. In fact, there were nineteen Lok children in all, which was sort of Michael’s problem. He did not inherit the family business (that went to Thomas, the eldest). If Michael wanted a fortune of his own, he’d have to make it himself.

He saw his opportunity in the shake-up of international trade caused by the Dutch conflict. Exporting cloth to Antwerp was the past. Lok was going to get in on the global future by establishing direct trade with the Orient.

His first step was to get in with the Muscovy Company, which had been founded by English merchants in the 1550s—around the same time Frobisher was marooned in Africa—originally under the name, “Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands.” It had been the first joint-stock company recognized in England, and a forerunner to the much more famous East India Company, which would be granted a royal charter in 1600.

As the name suggests, the point of the Muscovy Company was to conduct trade in Russia through Baltic-Sea ports. But the Company had a second mission too—to see if there was a way through the Russian arctic to the Orient. If they succeeded in this goal, the company men would be granted a monopoly on trade along the route they’d discovered.

Ultimately, that second mission came to nothing. Several attempts were made to find a way through the ice, but they all ended in disaster. By the 1560s, the Muscovy Company was content to focus on the more reliable business of trading in timber and furs from Russia.

But Michael Lok had bigger plans. The text of the company charter did not specify which direction the arctic explorers had to go. In other words, the same monopoly rights would apply whether it was a northeast trade route around Russia (the shorter and most obvious path), or a northwest trade route around America. Working within the Company, Lok began pushing his colleagues toward this latter, more ambitious project.

At the time, the Muscovy Company was facing a series of setbacks. The Russian Czar, Ivan IV (the notorious Ivan the Terrible) was a less-than-reliable trading partner. All too frequently, the Company suffered at Ivan’s autocratic whim. Arbitrary taxes were levied without warning (and without any hope of legal recourse, since Russia’s courts answered to the Czar). What’s worse, the Company couldn’t rely on the supposedly all-powerful Czar to protect their property. In 1571, the Company’s warehouse in Moscow was ransacked and destroyed by marauding Tatars.

And so, when Michael Lok pushed for a radical new direction for the Company, his colleagues started to listen.

By 1574, Lok had enough of them interested in moving forward. He also had support from Elizabeth’s advisors (especially her Secretary of State and spymaster, Francis Walsingham), who were interested in extending England’s global influence.

The one thing Lok was missing was a captain for this adventure. Who was courageous enough (or crazy enough) to sail into the icy unknown when every previous project had failed?

Lok found his answer in the young man whom his brother Thomas had once employed in his African projects—Martin Frobisher. Frobisher’s career as a quasi-pirate had not been particularly successful so far. But he had the qualities Lok was looking for—including persistence, and a proven ability to survive in the harshest of conditions.

Lok and Frobisher soon began what would prove to be a rocky relationship. In fact, the mutual animosity has clouded the origin story of their partnership. Frobisher claimed that the Northwest Passage project was his idea, something he had nursed since those conversations with that mysterious Portuguese explorer in his Lisbon prison cell. Lok, on the other hand, saw himself as the brains behind the project. Frobisher was just its public face.

Whatever the truth of the matter, by 1576 Lok and Frobisher were ready to undertake their grand mission—though “grand” may not be the right word. Lok had managed to convince his Muscovy colleagues and the government that any Northwestern Passage fell within the Company’s monopoly. But convincing them to invest in the project was another matter. Until Lok and Frobisher could prove the route was feasible, they would have to operate on a shoe-string budget.

They managed to raise enough money for three ships, but they were hardly titans of the sea. In fact, one of them was a pinnace (a glorified rowboat/landing craft). Typically, such a vessel would be carried on the deck of one of the larger ships. But in this case, the two larger ships weren’t much larger. Even the relatively small complement of sailors Frobisher brought with him (35 men in total) would have been uncomfortably cramped together on the two main ships, with the pinnace following in the rear.

Frobisher’s little fleet set out in early June, late in the season for a northern voyage, but the struggle to find financing had delayed things. In the end, Michael Lok ended up paying for half the costs out of his own pocket.

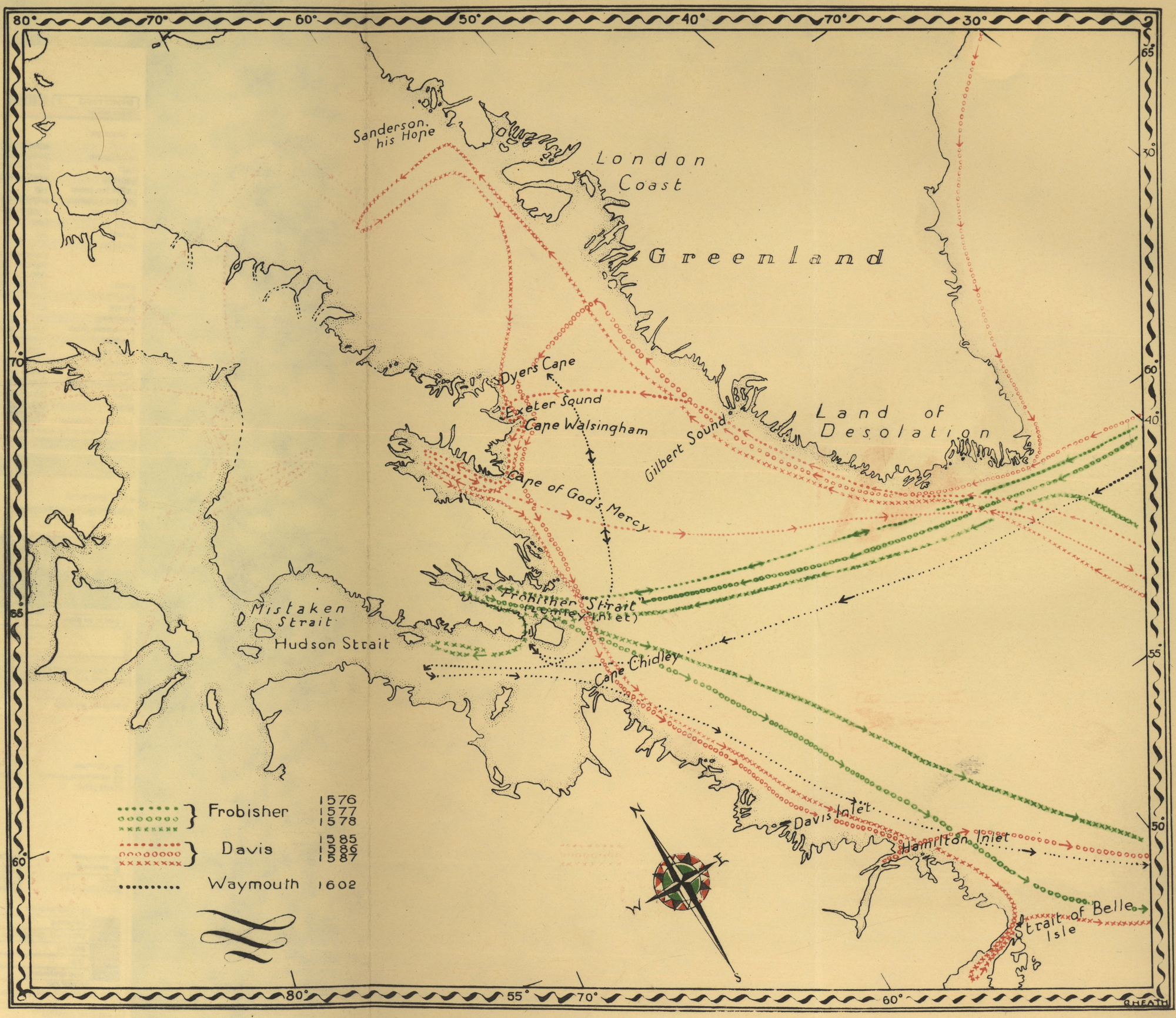

Previous attempts to find a northwest passage were not well documented, so Frobisher had little information to go on. Rumour had it that there was a channel at 60 degrees north, so he decided to sail to that latitude off the coast of Europe first, then head directly west. This took him to the Shetland islands, northeast of Scotland. On June 26, 1576, Frobisher set out into the open ocean.

He was surprised to sight land much sooner than he’d anticipated. Unfortunately, he could not find a safe way to approach the icy, rocky shore. After a few days spent poking around, Frobisher decided to push west and continue his search. But first, he claimed his newly discovered land in the name of the Queen. Of course, it was not newly “discovered” at all. Frobisher had hit on the southern tip of Greenland, first discovered and occupied by Europeans six centuries ago, and more recently re-discovered by the Portuguese at the beginning of the century. Frobisher’s ignorance is a testament to how poorly understood the far north was, even by the late 16th century.

West of Greenland, the voyage faced its first real challenge when the ships were hit by one of the North Atlantic Ocean’s frequent storms. The small pinnace was lost, along with its complement of four sailors. Meanwhile, the two main ships were separated. The Michael managed to limp to the Labrador coast, its crew of twelve unsure of the fate of the Gabriel, and their leader Martin Frobisher. In early August, seeing no sign of the Gabriel, they decided to head home. They brought with them the news that the voyage had been a failure, its brave captain lost.

But Frobisher, and 17 other men, were still very much alive, and determined to complete their mission. In late July, they hit a massive landform of ice and rock—Baffin Island. Just like with Greenland, Frobisher struggled to find a safe place to land—a task that was even more difficult now that he had lost the pinnace (a craft designed for manoeuvring close to shore). All they had to land men was a single rowboat that was not capable of exploring the coastline on its own.

After almost two weeks of searching, Frobisher finally found what looked like a safe harbour, on some small outlying islands off the east coast of Baffin Island. A landing party found nothing of interest on the barren terrain, except for a black lump that one of the men assumed was coal. He brought it back to the ship, where anything that might be burned for warmth was a welcome sight.

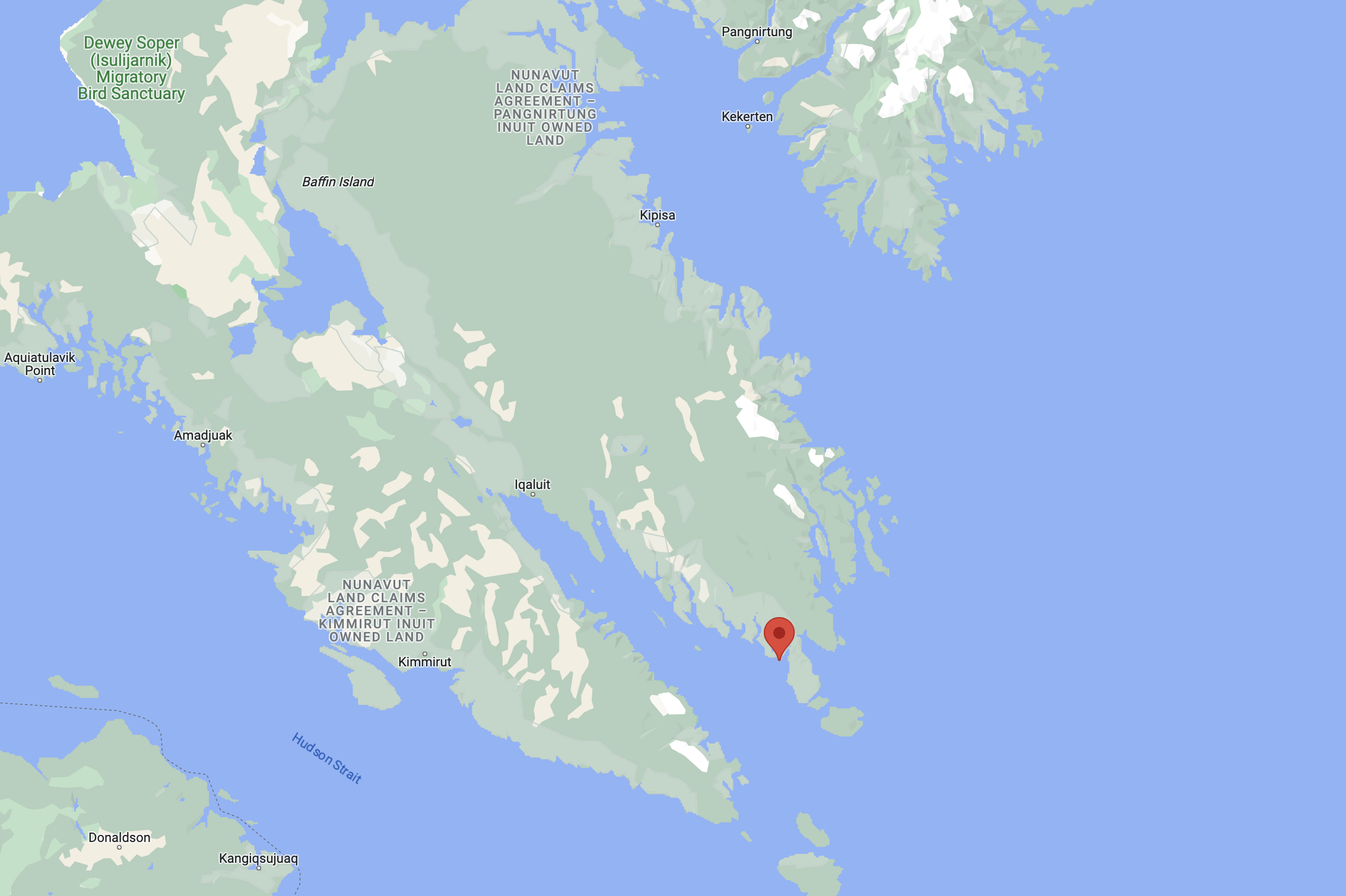

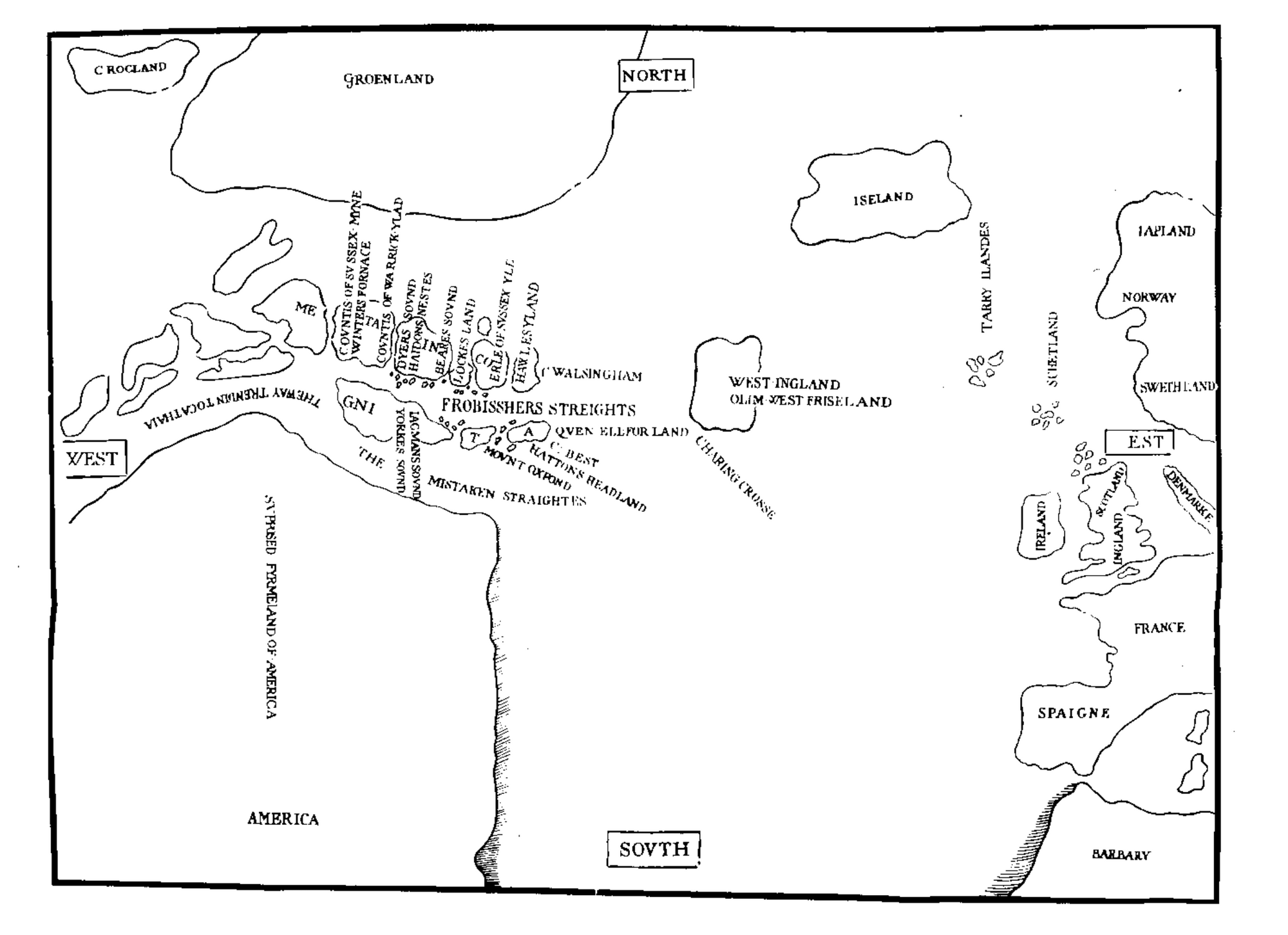

Frobisher was more interested in pushing on. After all, the goal was a passage through the ice and rock, not mineral deposits. And Frobisher thought he had found a lead: Around where the men had gone ashore, there was a massive gap in the coastline. Frobisher had discovered what became the aptly named Frobisher Bay.

Which was bad news for him. Because as the name suggests, this was not a passage through Baffin Island, but a long inlet. Frobisher was going down a dead end.

And at the rate he was moving, it’s unlikely that he would discover his mistake any time soon. The narrow bay (or channel, to Frobisher) was clogged with ice and rocky outcroppings. Unwilling to risk the safety of his ship (the only way to get back home), Frobisher moved carefully.

After several days of inching forward, Frobisher sighted another potential landing site about 150 km into the bay. This time, the men sent ashore discovered something much more exciting than a lump of coal. From a high inland ridge, they were able to spot several men paddling in small boats further down the coast. Frobisher had made contact with the Inuit.

Like the other European explorers we’ve seen so far, Frobisher reacted cautiously upon spotting Indigenous locals. Even more than Jacques Cartier at Stadacona, Frobisher was keenly aware of how vulnerable he was. He had only 18 men with him, and he was far, far from home. The Inuit approached with caution, as well. From a distance, Frobisher thought their one-man kayaks looked like “porpoises, or seals, or some kind of strange fish.”

The groups kept their distance from one another on the water, but both dispatched emissaries to meet on dry ground. Without any common language, only rudimentary communication was possible. But a group of Inuit eventually agreed to come aboard the Gabriel as guests. One of Frobisher’s men (a veteran of several voyages to Russia) noted of these strangers, “they be like to Tartars [a variant spelling of Tatars].”

The conference seemed to go well. The Inuit offered gifts of seal skins, meat, and fish, while the Englishmen offered metal tools and various ornaments they had brought as samples to show off English craftsmanship to Oriental traders. Like the Mi’kmaq whom Cartier encountered in his initial voyage, the Inuit seemed accustomed to trading with Europeans.

Before the Inuit departed, they extended an invitation to Frobisher to visit their settlement nearby. Two days later, Frobisher and four of his men took them up on the offer. Typically, an Inuit settlement would have included several families—a large enough group to supply the dozen or so adult males needed to crew an umiak. That meant Frobisher and his crew were outnumbered. But Frobisher was getting more comfortable now. What he initially perceived as a threat was turning into the most promising development of the voyage so far, as a local guide would be invaluable to his mission.

Again, communication was difficult. But by the time Frobisher returned to the Gabriel, he was confident that he had secured the agreement of one of the Inuit to act as a guide. Ideally, they could set off right away. And in fact, the man Frobisher presumed he’d just recruited accompanied him back to the ship.

But here’s where the story gets a bit muddled. Again, just like in the case of Jacques Cartier and the Stadaconans, we only get the European version of the story. We know what Frobisher was attempting to communicate to the Inuit, but how they actually understood things is a mystery.

According to Frobisher, his guide was eager to help out, but couldn’t leave right away. After a few minutes on the Gabriel, he indicated to the English that he would have to return home to gather the supplies necessary for a long trip. Frobisher readily agreed, and ordered five of his men to row the Inuk guide back home, collect what was needed, and bring him back. (An Inuit person is commonly referred to as an Inuk.)

However, for the next two days Frobisher saw no sign of his men or his boat. Fearing that he was in fact facing a hostile force, Frobisher panicked. His ship was down to a complement of twelve men, barely enough to get them back across the Atlantic. And with the loss of the rowboat, they had no way of putting in to shore. They were sitting ducks in an inhospitable and alien land.

Worse still, it was the last week of August. By now, the fishermen in Newfoundland were packing up and heading home, before the ice forced them to spend the winter in Canada. And Frobisher was almost 2,000 km deeper in the icy danger zone than those sailors.

Hoping that a display of force might intimidate the Inuit (or maybe just get their attention), Frobisher moved in as close to the Inuit camp as he could and fired off a small cannon he had on board his ship. But it was a futile gesture. If his men had been abducted or otherwise injured, there was little he could do about it.

Frobisher decided to alter his approach. Remembering that the Inuit were interested in many of his goods, he sought to entice some of them to his ship by holding out objects for trade. Some kayaks came out, but kept a cautious distance. We have no idea how the Inuit understood the situation they found themselves in, but they must have sensed that the goodwill these strangers had demonstrated a few days ago had disappeared.

After much cajoling, Frobisher got one curious shopper to get within arm’s length of the ship. Suddenly, his entire kayak was lifted out of the water and dumped on the deck. Frobisher now had a hostage with which to buy back his men.

But either the Inuit did not consider the captured Englishmen to be hostages, or they could not understand Frobisher’s attempt to negotiate an exchange. Frustrated and fearful of both the Inuit and the oncoming winter, Frobisher decided to cut his losses and get back home while he still could. It was a dispiriting end to the first voyage of Frobisher’s new career as an explorer.

The Gabriel arrived back in England in the Fall of 1576, to the surprise of everyone (since Frobisher and his crew were thought to have died during their initial crossing).

The trip produced three significant outcomes. First, Frobisher was confident that he’d found a passage through North America. As it turned out of course, he hadn’t. He had discovered Frobisher Bay, not the Frobisher Channel. (Had the Gabriel hit North America just a degree further south, Frobisher would have found an actual channel between Baffin Island and continental Canada. But that discovery would have to wait one more generation.)

The second significant item Frobisher brought back from his trip was an Inuit kayak—and, more importantly, the Inuk man who’d been using it. After his failure to ransom his hostage, Frobisher had decided to bring the man back to Europe (just as Cartier did with the Stadaconan brothers). If he could be taught English, he might serve as a useful translator and guide for future voyages.

Frobisher’s Inuk hostage was an instant sensation back in England. At least two court artists produced portraits of the strange visitor. However, the excitement was short-lived. Just days after his arrival in England, Frobisher’s would-be guide died of one of the many European diseases to which he’d suddenly been exposed.

The third find that Frobisher brought back might seem barely worth mentioning—the hunk of coal one of his men had spotted on their first landfall. It certainly seems that Frobisher didn’t give the black lump much thought. But it would radically alter the whole project. By the time Frobisher set out on his second expedition the following summer, finding a passage to the Orient had become an afterthought. It had been supplanted by a much grander prize.

To understand what that new goal was, we’ll have to return to the man who footed the bill for Frobisher’s voyage—Michael Lok. Lok had sunk much of his personal fortune, as well as his reputation, on the success of the voyage. Even more than Frobisher himself, he needed the enterprise to succeed. Lok was a desperate man, willing to grasp on to anything that might offer hope. Frobisher’s report of an ice-choked channel that may or may not lead anywhere wasn’t exactly a ringing endorsement of their work. Lok was anxious for something more tangible.

And it doesn’t get much more tangible than mineral wealth. Frobisher presented the black lump to Lok as a memento of the voyage. Upon closer inspection, the crew of the ship had determined that it was not, in fact, coal, but some other kind of mineral. Lok took it directly the royal assayers at the mint. They informed him that it was marcasite, iron sulfide in crystalline form. In commercial terms, it was worthless. In fact, it was in the same family of minerals as the fool’s gold that Cartier had found on the St. Lawrence.

This was not the answer Lok was looking for, and so he sought out a second opinion. In January 1577, he found his man in Goivanni Baptista Agnello, a Protestant refugee from Venice. Agnello worked in London’s goldsmithing industry (in which continental migrants were well represented). Recognizing in Lok a man desperate for good news, Agnello claimed that the rock contained a significant amount of gold ore. It would take a far more sophisticated furnace than he currently owned to extract the gold, but his preliminary tests were absolutely definitive.

It was this news (rather than Frobisher’s reports of a channel) that spurred interest in a follow-up voyage. Francis Walsingham (Lok’s contact in government) initially dismissed the report as “an alchemist matter,” but then seems to have been won over by the confidence of Agnello’s assessment. Due to a lack of specialized knowledge among the English, foreign metal workers were more trusted than royal officials.

A whole slew of new investors now approached Michael Lok, hoping to get in on what was starting to look more like a gold-mining company rather than one focused on oriental trade. After all, that’s how Spain’s global empire had been born. Queen Elizabeth herself invested £1000, and contributed a royal ship to the expedition.

The Queen also chartered a new Company, the Cathay Company, to oversee the venture (with Michael Lok at its head, of course). Like the Muscovy Company, it would be organized on a joint-stock basis, with shares of the company being bought up (and eventually sold) by many shareholders.

Resource extraction was front and centre in the Company’s charter, with the prospective passage to the Orient included as a mere afterthought. The fleet (now expanded to three ships) was to carry a group of miners, and a professional assayer of gold (once again, not an Englishman, but a German named Jonas Schutz).

Frobisher was also tasked with a few side missions. His passenger manifest included a group of convicts who were to be left in the arctic over the winter. Much as with the French attempt to colonize the St. Lawrence, the English turned to convicted criminals rather than the more expensive option of recruiting willing settlers. No matter their rap sheet, their presence would fulfill a key criterion under international law (such as it then was): If English subjects lived all year round on Baffin Island, their presence would confirm Elizabeth’s claim to the territory in a way that seasonal explorers or fishing vessels could not.

The Queen also tasked Frobisher with improving relations with the Inuit—though, paradoxically, she ordered him to achieve this goal by abducting a handful of them and bringing them back to England in a kind of (forced) cultural-exchange program. Future English explorers could learn Inuit customs and local geography, which would aid in their work, while the Inuit could learn English, and act as translators. Much like Cartier, the English failed to anticipate the reputational damage they would incur due to such forced abductions.

On May 31, 1577, Frobisher set out, this time with a team of 160 men spread across three ships. The problem was that the expedition organizers had accounted for only 120. (It seems that the promise of gold attracted a few unofficial volunteers.)

In order to correct the matter, Frobisher put in on the English coast on his way north and left forty men on shore. For the most part, these were the convicts who’d been picked to spend the winter on Baffin Island. Frobisher was likely glad to be rid of them. And it’s possible they were glad to go as well. There’s no indication that Frobisher transferred them to the custody of any local authority figure: He simply pushed them off the ship and let them go about their business.

By mid-July, the expedition was back in Frobisher Bay. But this time, instead of looking for a passage through the ice, they were looking for black rocks on shore. Frobisher scoured the north side of the bay with the Gabriel, while the Queen’s ship, the Ayde, searched the south.

Frobisher found plenty of black rocks on his side. But before he could sight a suitable place to set up a mining camp, he came across a group of Inuit. Just as in the previous year, they were wary, but seemed interested in trade. Frobisher had other plans, though. Partly, he was thinking of his mission to bring some of these locals back to England. But he had not forgotten the five sailors he’d lost the previous year. This was an opportunity to seize hostages, and possibly negotiate the return of his men, assuming they were still alive.

The two groups kept their distance, and each sent a two-man delegation to meet on neutral ground. When they met face-to-face, Frobisher (who was acting as one of the English delegates) attempted to grab his Inuk counterpart and carry him back to his ship. A scuffle ensued, and both groups rushed forward. Frobisher managed to escape the melee with an Inuit arrow lodged in his backside and a single hostage. (One of his crew, a Cornish sailor renowned for his wrestling skills, had tackled the Inuk man, crushing his ribs in the process.)

Frobisher had his first “volunteer” for the Queen’s cultural-exchange program. But this was not doing much to further the goal of improving Anglo-Inuit relations.

Meanwhile, on the south side of the bay, the crew of the Ayde were doing their own part to sour relations with the local population. They had a golden opportunity to fulfill the Queen’s desire for foreign guests when they came across an Inuit settlement. Thanks to their superior numbers (the Ayde’s crew was more than double the combined complement of the other two ships), they were able to surround the camp. The terrified Inuit made a desperate bid to fight their way out of the trap, and the English killed five or six of them in the confused battle that followed.

Most of the Inuit escaped in their kayaks, but they were forced to leave behind a child and two women. The younger woman and the child were led to the ship. But the other woman was believed to be probably too old to survive the trip back across the Atlantic, and so she was released—though not before the men stripped her, “to see if she were cloven footed.” (This quote, like much of the information we have concerning this voyage, comes from a book subsequently written by one of Frobisher’s crewmates, Dionyse Settle, A True Reporte of the Laste Voyage Into the West and Northwest Regions.

While exploring the remains of the Inuit camp, the English came across a set of European-style clothes, which had been torn quite badly. The immediate assumption was that they belonged to the men who had been lost the previous year. A ghoulish and much less well-founded assumption soon followed: the heathen Inuit had eaten these Englishmen as part of some kind of dark ritual. A fear of cannibalism, fuelled by rumours and fantastical reports about the New World in popular media back home, had hung over the expedition from the beginning.

On the August 3, the ships re-united at Kodlunarn Island, on the north side of Frobisher bay, near its mouth. There were more promising mining sites, but Frobisher was worried about security. The Inuit were clearly hostile (for reasons that no modern reader will fail to find understandable), and so it was too dangerous to send out miners without protection. Best to choose an easily defensible island and keep everyone close together.

As Frobisher expected, a group of Inuit soon appeared near the island. It is likely they came from the same community Frobisher had encountered a few weeks earlier, their numbers possibly supplemented by a call-to-arms to deal with this alien threat. A stand-off ensued, with the Inuit too cautious to approach such a large assembly of Englishmen, and Frobisher’s men too wary to stray outside their defensive positions.

Instead of fighting, the Inuit sent a diplomatic delegation to negotiate. Language was still a barrier. But quite clearly, the Inuit wanted Frobisher’s captives returned to them. Frobisher replied with his own demand for the return of the five men who’d been seized the year before. The Inuit appeared to know what Frobisher was talking about, and indicated that they would return in three days with proof that the men still lived.

Neither Frobisher nor his men believed this for a second. This was clearly a ploy to buy time. George Best, one of Frobisher’s deputies, was one of many who believed their expedition was in grave danger. “Our flesh is so sweet meat for them,” Best (dubiously) claimed, “that they will hardly part from so good morsels.”

Whether the five Englishmen were still alive is a bit of a mystery. It’s likely that they survived for at least a few months. Inuit oral tradition tells of a group of five Europeans who lived among the Inuit for a winter, but that they died trying to re-cross the Atlantic on a makeshift boat. These may well have been Frobisher’s men, though the tradition gives no clue as to how they ended up living among the Inuit.

Perhaps the Inuit had killed the men, or perhaps they had died over the winter of other causes. Either way, Frobisher did not trust the Inuit claims. That distrust seemed well-founded when three days passed without any word from the Inuit. In fact, the situation only seemed to grow more menacing. Likely, the Inuit understood that Frobisher would release his prisoners only in exchange for Englishmen. So they intended to seize any opportunity they could to procure one to trade.

The standoff held until the third week of August. Every morning, the men had to break up the ice that had congealed around the ships during the previous night. Time was running out. They had to return to England before their ships were permanently trapped.

Establishing a winter colony was impossible under such circumstances, but Frobisher had completed his other two objectives. Although security concerns had limited the mining operation, the ships were well laden with black rock. And the scars cut into the ground on Kodlunarn Island by English miners are still visible today. Frobisher also had three Inuit prisoners—the man his Cornish wrestler had captured, and the woman and child that the crew of the Ayde had seized.

As it turned out, two out of three was enough to rate the voyage a fabulous success. Again, the Inuit visitors were a sensation. The man, named Kalicho, impressed crowds of English men and women by paddling his kayak up and down the Bristol Avon. However, he died a few weeks after his arrival in England. An examination of his body revealed that he had a collapsed lung and several broken ribs, suffered at the hands of his Cornish captor.

The English called the Inuit woman Egnock, though that appears to have been an anglicization of the Inuit word for “woman” (ᐊᕐᓇᖅ arnaq) rather than her name. She, too, died a few weeks after landing in Bristol, whereupon she was buried as a “heathen” in a local church. The baby, known as Nutaaq, survived a bit longer, and was transported to London, but soon succumbed to measles.

The English attempt to establish relations with the Inuit was an unmitigated disaster, both morally and practically. The abductions had only served to alienate the Inuit, at the cost of several lives. And the English were no closer to knowing anything about Inuit language or customs, nor the geography of the arctic.

But by this point, all of this, like the possible passage to the Orient, had become a sideshow to the question of whether gold might be extracted from the arctic rocks. The ships full of the stuff supposedly offered proof that this was something more than just some alchemist’s fever dream. Powerful forces in the English government were taking the project seriously, and the rest of Europe noticed. The Spanish ambassador even bribed one of Frobisher’s men to be Spain’s eyes and ears on the inside. And the French floated the idea of becoming joint investors in Elizabeth’s operations.

The gold itself remained shrouded in mystery, however. Although Agnello (the Italian goldsmith) had claimed he could extract gold from the original rock sample, he had not actually done so yet. He claimed he needed a larger specimen, and larger ovens to work with. The Privy Council kept tight controls on the recently arrived shipments. Only the Queen’s top advisors (and Michael Lok) were kept abreast of the assessment of the goods.

Jonas Schutz, the German metallurgist who’d joined the expedition, took over as the top analyst. He gave a more conservative estimate of the gold contained within the rocks, estimating 40 pounds of pure gold per ton (less than the 240 pounds per ton that Agnello had projected, but still a good haul). Frustratingly, this was still just an estimate though. Like Agnello, Schutz claimed he did not have the facilities necessary to extract the precious metal. Until he had a state-of-the-art apparatus (paid for by the Company and the Crown, of course), work could not begin.

As a result of these delays, investors got nervous through the winter of 1577-1578. It had been months since the cargo was unloaded, and there was still no evidence of any gold emerging from the rocks. Until the Company was able to produce actual gold, attracting new investors would be impossible. Even worse, some of the existing investors were warning Michael Lok that they might have to pull out.

At this point Lok was in over his head. Whether the gold was real or not almost didn’t matter. He’d been keeping the project alive on a shoestring from the beginning, and he was now fully committed to its success. If his dream was to survive, he needed to raise confidence by outfitting another voyage in 1578.

So, despite the uncertainty still surrounding the gold, he issued a double-or-nothing threat to his investors: If the project failed now, they would lose all their money. If they wanted to avoid ruin, they needed to back him one more time, for a third expedition—the scope of which would dwarf their previous efforts.

In order to retain their share of the profits, Lok demanded that each investor buy in again, at higher rates than before. Since Lok seemingly had the confidence of the government, the investors complied.

The new round of funding was enough to build a massive smelting facility at Dartford, in Kent, and mount another, much larger expedition in the summer of 1578.

In fact, the 1578 voyage still ranks as the largest ever attempted in the Canadian arctic. Officially, the fleet consisted of ten vessels, but several independent ships also tagged along, in hopes of cashing in on the gold rush. In total, 400 men set out, about 100 of whom were to remain in the arctic all winter. The expedition even brought enough lumber to build an entire settlement (a necessity as there were no trees on location).

The weather would only permit mining for a few weeks in the summer. But as noted above, a permanent colony was crucial for England’s claim to the land. As historian James McDermott puts it, most of the colonists’ time “would be devoted to the more mundane task of not dying.”

Again, the ships set out on the May 31, and were at the mouth of Frobisher Bay by the beginning of July. At least, most of them were. Rough seas once again scattered the fleet, and Frobisher’s ship was pushed off course. He went a few hundred kilometers down the Hudson Strait before realizing his error and turning back. (Without knowing it, he’d stumbled on the passage between Baffin Island and continental North America—the opening leg of a true Northwest Passage.)

While Frobisher was busy getting lost, the rest of the fleet was getting into its own trouble. The gold-hungry captains were eager to push into the bay and start mining as soon as possible. Every day they waited was another load of gold they wouldn’t be carrying back home. But the voyage’s top pilot, Christopher Hall (who had been on Frobisher’s first two voyages) urged caution. The Bay was narrow and treacherous, and was far too clogged with ice at the moment. Best to wait a few days, and let the warmth of the summer do its work.

Hall was just a pilot though, and was out-ranked by the inexperienced captains. On July 2, they sailed into the bay and were immediately surrounded by ice. The ships holding up the rear were able to escape, but eight vessels were trapped. They spent a terrifying night, battling lumbering chunks of ice. Crews tied mattresses to the sides of their ships to act as bumpers, and men grabbed whatever poles they could find to push the approaching ice away. The bravest men went out in rowboats and swarmed toward whichever ship seemed to be in the most danger.

In the aftermath, the bay looked something akin to a battlefield. Every ship was badly battered, but miraculously only one of them had gone down. Unfortunately, the ship that had been lost was the one carrying the bulk of the building supplies for the settlement. It wasn’t clear how they’d be able to construct a colony now—especially since much of the lumber stored on the other ships had been used up fighting the ice.

Also, while most of the ships had been able to fight their way back to the open sea when the ice cleared the next morning, not everyone had been so lucky. The commander of the planned new colony, Edward Fenton, was on the Judith, which had become firmly lodged in the ice during the night. It would take three weeks of combat against the implacable ice before Fenton and his men were able to get ashore.

It was a month before the bulk of the fleet (now re-joined by Frobisher) was ready to brave the bay again. On July 30, they landed at base camp, and found that Edward Fenton and his marooned comrades had already set up shop a week earlier. However, without equipment, Fenton and his men had not been able to do any mining yet. Nor did they have the materials to build a permanent settlement.

With the arrival of the main fleet, the work could begin. Judging by the previous voyages, the miners had less than a month to gather as much ore as they could before the ice made the return voyage impossible. On the positive side, the sheer size of this new English operation had apparently scared off any Inuit in the area.

While the miners worked over-time to make up for the late start, the expeditions’ leaders held a conference. Fenton stepped forward and bravely (or more accurately, insanely) offered to stay the winter. While the materials they had planned on using to build a permanent settlement were at the bottom of the bay, Fenton was confident that he and 60 men could make do with a few makeshift shacks. Everyone else saw this for the suicide mission it would be, and convinced Fenton to back down. Instead, they redoubled their efforts on mining, literally working around forty men to death in the process. By the end of August, they had an impressive 1,300 tons of rock in their holds (as compared to the 200 tons brought back on the second voyage).

Before leaving, they used what wood they had to build a small house. It was a bit of an experiment to see how the structure would hold up over a winter. They also still hoped to establish friendly relations with the Inuit, and so left in the house some of the European goods the locals had expressed an interest in, as well as a loaf of bread for the Inuit to try.

The rest of the excess food, which had been intended for winter use, was buried, in hopes that next year’s expedition could make use of it. On August 31, the English departed.

On the surface, the operation had been a qualified success. Despite the short time window, the ships actually brought back more ore than expected. But while Frobisher had been on the other side of the Atlantic, the doubts surrounding the value of the rocks had only continued to grow.

In June, Spanish agents finally got their hands on a sample. And they concluded that it was quite obviously worthless marcasite. In fact, it was so obviously worthless that, at first, the Spanish thought their spy had been duped. There was no way the English could be stupid enough to invest so much in a bunch of common rocks.

But after the return of the third expedition, it was impossible to continue hiding the truth. In November and December, rumours started to fly that there was no gold at all. Investors decided to cut their losses and pull out before Michael Lok demanded yet more money out of them. Frobisher turned on his partner, accusing him of cooking the Company books. Lok countered by insulting Frobisher as an incompetent pirate whose mistakes had undermined the whole project.

While neither man came out of the business smelling like roses, Lok got the worst of it. He would spend the next few years in and out of prison on various charges of fraud and non-payment of debts. Frobisher returned to his career of service to the Crown, working the fuzzy line between anti-Spanish warfare and piracy.

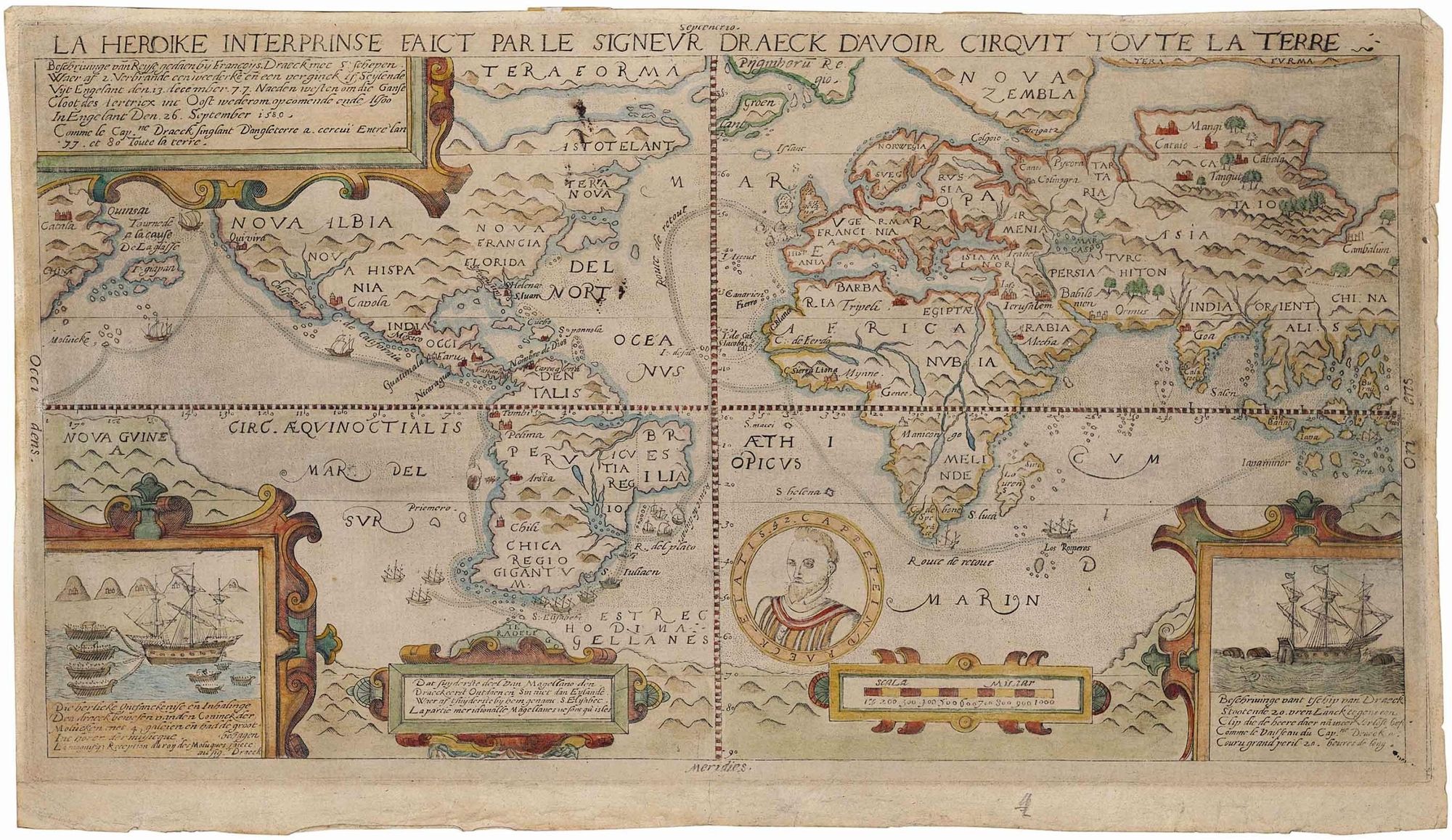

The Lok/Frobisher escapade had a lasting influence on England’s overseas policy. Francis Drake’s voyage around the world (which returned to England in 1580, about a year after Frobisher’s arctic gold was revealed to be a mirage), was far more profitable. And Drake’s success would influence English thinking for the next fifty years: The way to make money on the high seas was to raid Spain’s vulnerable shipping lanes, not carve out a new passage to the Orient. This became easier once England officially intervened in the war between the Dutch and the Spanish in the 1580s.

The arctic experience also influenced England’s approach to colonization. The climate in the north was too inhospitable, and the land too barren. When Elizabeth sponsored her next attempt at a permanent settlement in America (some ten years later), she chose a destination much further south—modern-day Virginia. This first attempt, known as the Colony of Virginia, failed. But the English would continue to see the south as the only viable place for settlement.

I mentioned at the outset that Frobisher’s voyages shared certain similarities with Cartier’s on the St. Lawrence. Both had originally set out to find a passage to the Orient, but both found that task much harder than they imagined. Instead, Frobisher and Cartier turned to the promise of valuable commodities that they found in the lands they’d searched. For both of them, that promise evaporated as soon as they returned to Europe.

To this point, the only Europeans who’d made a success of their trips to Canada were the seasonal fishermen and whalers plying the coasts. Until Canada’s mainland offered up a commodity as valuable as salt cod or whale oil, European interest would be limited.

In the next installment, we’ll track the emergence of just such a commodity. In the years immediately following Frobisher’s third and final expedition, there was a dramatic rise in the number of European ships sailing into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. But these captains were not chasing fish, or whales, but fur.