The Retreat from Moscow

Prigozhin’s coup attempt raises a number of questions to which there are no reassuring answers.

In his inflamed response to what seems to have been a coup attempt led by his one-time ally Yevgenny Prigozhin, President Vladimir Putin invoked the year 1917. He did so not to celebrate the Bolshevik revolution of that year, but to remind his audience of the chaos that ensued when Russian troops gave up fighting the Germans and returned, angry and unpaid, to Moscow. The Tsar, Nicholas II, was toppled and murdered, along with his large family. The coup by Prigozhin’s Wagner mercenaries has apparently been called off (at least for now), but it raises the question: is this Putin’s Nicholas II moment?

Is Putin facing his Czar Nicholas II moment? https://t.co/oN3jsvp8ah

— Anne Applebaum (@anneapplebaum) June 24, 2023

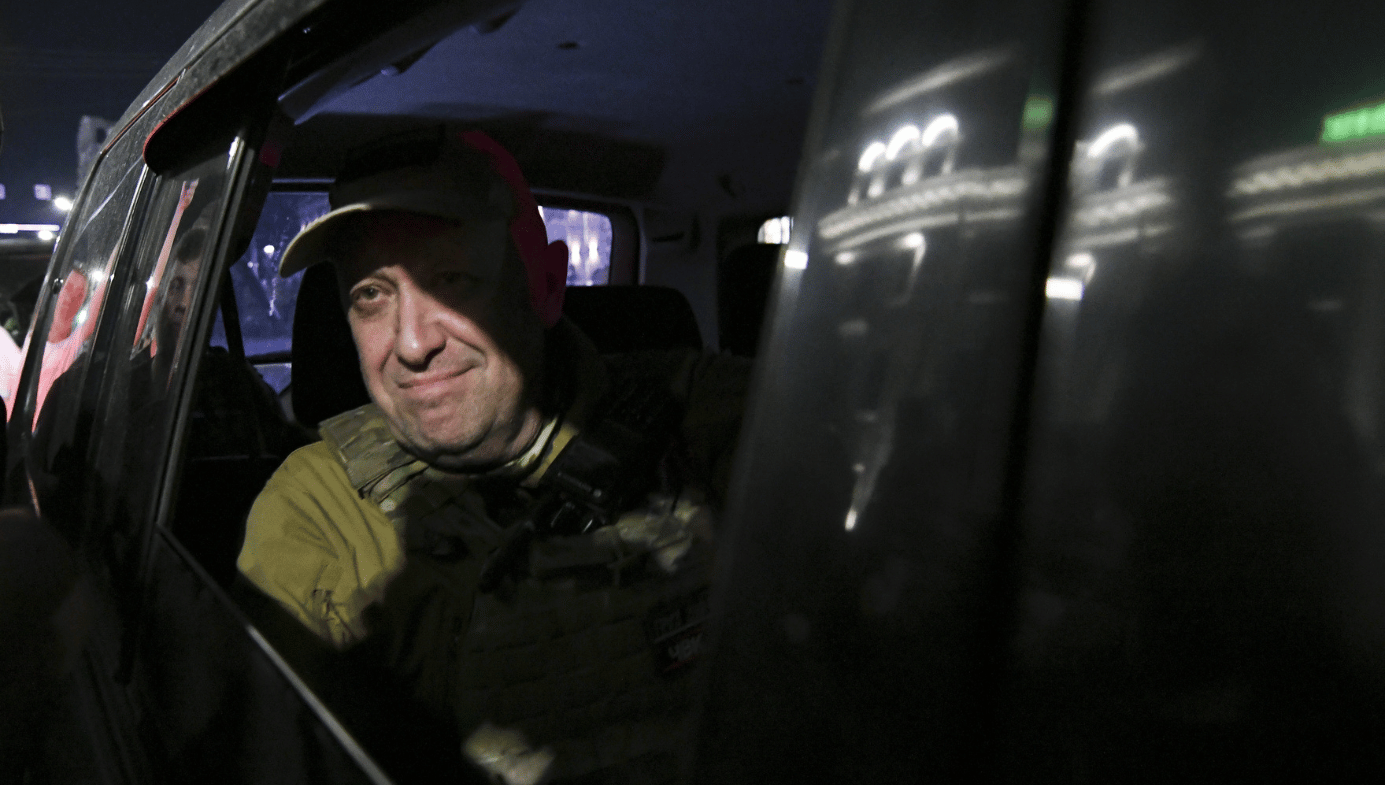

For the time being, the situation confirms Winston Churchill’s 1939 remark that Russia “is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” The facts of what happened over the weekend, insofar as they are known, make no immediate sense. On Friday, June 23rd, Prigozhin and his army of 25,000 battle-hardened and brutal soldiers crossed into Russia from Ukraine and headed for the southern city of Rostov-on-Don, where the headquarters of the Russian armies are sited. There, according to their leader, they were welcomed, or at least not repelled, not only by the people but also by senior Russian commanders. Having secured an important objective, they set off for Moscow, while the world awaited the beginning of a civil war.

Putin first delivered a speech of vengeance; the president of the small neighbouring state of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, arrived to mediate; Prigozhin (and presumably his army) agreed to divert his march from Moscow to Belarus; and Putin announced that charges would be dropped, as if treasonous insurrection during wartime were merely a forgettable tiff among old friends and rivals. Prigozhin had, as usual, not held Putin personally responsible for his grievances, a precaution against cutting their ties completely. In response to Putin’s sulphurous threats, he responded (mildly for him) that “the president makes a deep mistake when he talks about treason. We are patriots of our motherland, we fought and are fighting for it. We don’t want the country to continue to live in corruption, deceit and bureaucracy.”

On Monday, Putin returned with another speech, which this time thanked everyone for saving Russia from a coup and civil war, including the Wagner commanders (he did not mention Prigozhin by name) for controlling their troops. Meant as an important clarification of where the country stands, and touted as such by his press secretary, it only applied another coat of obscurity. Putin seems to be trying to decompress the rhetoric which has surrounded the Ukraine war since before it began. Some of the most extreme propagandists on TV, the dominant medium in Russia, have watched their audiences start to decline, and antiwar themes, so far mostly confined to the Internet and social media, have begun to filter into the media and the national conversation. Limited though that development has been, it appears to be alarming the Kremlin.

In one of several senseless instances of which we must now try to make sense in this puzzling episode, Prigozhin appeared to believe he could take Moscow with less than usually incompetent officers. Russia’s best troops may be in Ukraine, but Putin has the National Guard at his disposal—a force 340,000 strong, separate from the regular military, which reports directly to him. They were deployed near Rostov on Saturday night, but appear not to have engaged the Wagner forces. How could someone as experienced as Prigozhin believe he could win once battle was joined? And if he didn’t think he could win, then what was he thinking? And why has he accepted the terms of a deal that surely leave him in mortal danger?

Prigozhin is unlikely to find a secure sanctuary in Belarus. Lukashenko, a dictator who relies on constant force to suppress a restive citizenry of 10 million, is beholden to Putin for cheap energy and support for repression. Were Putin to change his mind about forgetting the whole thing—and that is more likely than not—he would expect to find Lukashenko helpful in detaining Prigozhin. Putin was not in the KGB to learn table manners, after all.

One possible reason for the warlord’s turnabout on the road to Moscow, according to a report in the Daily Telegraph, was that he was told a continued march on the capital would not—how can we put it?—be good for the health of his family. Another possible explanation—they come thick and fast in the fog of war—is a variation of Prigozhin’s own rationale: that he didn’t want to spill Russian blood. His column was reportedly attacked from the air, several helicopters were shot down, and some 30 Wagner men were killed. Careful of his men (and of himself), he wisely turned back.

Summary of Prigozhin's 26 June address to clarify the situation: it was to demonstrate protest against the "destruction of PMC Wagner, not toppling the Russian authorities":

— Dmitri (@wartranslated) June 26, 2023

What were the prerequisites for the March for Justice?

- PMC Wagner carries out tasks around the world.…

Prigozhin could, of course, resume operations in Ukraine, and make himself indispensable to the Russian effort. Ukrainian counterattacks have yet to be wholly successful, but they are nevertheless re-taking territory in increments. Every commentator believes that Putin has been weakened, not just by Prigozhin’s mutinous challenge, but also by the abrupt decision to abandon what would have been cruel (but usual) punishment. From that decision, myriad other questions arise, all of which Putin and his commanders will have to confront going forward. Once these facts are digested by the Russian armies in Ukraine, will they still be willing to fight for someone who will not fight for himself? Is Prigozhin merely biding his time before a second assault? Does the Wagner chief actually have his eye on the presidency? And does he have allies among Putin’s inner circle?

Assuming that the hellish war in Ukraine continues for some time, Putin now has to figure out what to do with his own commanders. His chief of the general staff, Valery Gerasimov, and especially his defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, have both demonstrated that they are not up to the job. In a short but scathing essay for UnHerd, the US historian and military strategist Edward Luttwak dismissed both Shoigu and Gerasimov as men unable to rise to the occasion of a hot war. Prigozhin, Luttwak wrote, had “started to voice his complaints increasingly loudly, eventually asking why Shoigu and Gerasimov were still in-command when they should have been shot for incompetence, or at least kicked out of their jobs. Inexplicably—not only to him—Putin failed to take advantage of his dictatorial power to get rid of the pair of failures.”

The Wagner leader has also pointed out that the Russian invasion of Ukraine last year was predicated on a lie peddled by the Minister of Defence. “There was nothing extraordinary happening on the eve of February 24,” he wrote on his Telegram channel:

The Ministry of Defence is trying to deceive the public and the president and spin the story that there were insane levels of aggression from the Ukrainian side and that they were going to attack us together with the whole Nato block. The special operation was started for a completely different reason.

That reason, he hinted, was that the ruling group hoped to enrich itself with the spoils of what they believed would be a successful and rapid conquest.

This version of events is closer to the truth than Putin’s risible claim that Ukrainian Nazis had taken over the government in Kiev. Once this is absorbed and discussed by ordinary Russians, many thousands of whom will have close relatives at the front, it will further destabilise the Kremlin’s already shaky grip on power. On NBC’s Meet the Press, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said (not without schadenfreude) that the disruption Prigozhin has caused is “just the latest chapter in a book of failure that Putin has written for himself and for Russia. … Prigozhin himself, in this entire incident, has raised profound questions about the very premises for Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in the first place.” Naturally, a little later than usual, the West was blamed.

BREAKING: Russia's foreign minister says the country's agencies are investigating whether Western special services were involved in the Wagner rebellion

— The Spectator Index (@spectatorindex) June 26, 2023

The consensus among most Russian and foreign observers is that Putin knows how to retain power by pitting possible rivals against one another. In this way, he keeps them busy with feuds rather than allowing them to build support for a serious attempt against him. Even though no single contender for the presidency has yet emerged, that game may be nearing its end.

In the New Yorker, Joshua Yaffa, one of the most subtle and well-informed of Russia watchers, wrote that:

Wars abroad have a way of unleashing uncontrollable political processes at home. Power everywhere, but especially in an autocracy such as Putin’s Russia, is ultimately a myth—a kind of collective agreement, often subconscious, to acknowledge and abide by the authority of a given individual. Putin, at least for now, appears to have put down the Prigozhin coup, but the myth that undergirds his rule will have taken its most serious hit yet, and the echoes of 1917 may prove far closer than Putin would like to imagine.

In this shifting and shadowy scene, yet another possibility exists—one which carries less disastrous overtones than many of the alternatives. Wolfgang Munchau’s EuroIntelligence briefing on Monday raised the intriguing possibility that the Russian regime is now looking for some sort of exit:

Putin’s notion that Ukraine is integral to Russia has disappeared from the discourse. … There was a lot of media coverage of the trip of a delegation of African presidents to Moscow recently, who showed an interest in mediating between the two sides. A commentary in the Russian news agency RIA expressed regret that all the previous attempts to broker a deal had failed, including China’s 12-point plan. It concluded with the observation that the “great patriotic war has ruined us, and produced a demographic catastrophe for future generations.”

[...]

Margarita Simonyan, the editor of Russia Today, and one of the hard-liners in the early days of the war, is now talking about an armistice and a demilitarised zone, secured by the UN. She even asked the question of whether Russia needs territories whose inhabitants do not want to be Russian.

Such a multifaceted shift is surely not accidental.

However Putin’s rule may end or continue, the larger and unanswerable question remains that of Russia’s post-Putin future. Lists of possible candidates are being circulated, with the Prime Minister, Mikhail Mishustin, as a leading moderate, together with Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin. On the hardline side, a continuation of Putin by other men, is Nikolai Patrushev, secretary of the Security Council. A longer shot is his 54-year-old son, Dmitry, who presently serves as Agriculture Minister.

Even after his mutiny, Prigozhin remains on the list, though the British Russia expert Mark Galeotti observes that, “You would have to have an absolutely catastrophic collapse of the state” for the warlord to assume power. And such a development would spread panic around the globe. Still, such a possibility cannot be discounted on that basis. After all, spreading global fear in generous quantities is presently Russia’s chief contribution to world politics.