Art and Culture

‘The Princess Bride’ at 50

A look back at William Goldman’s bonkers metafictional novel ‘The Princess Bride,’ which later became a much-loved family film.

Even by the eccentric standards of fantasy literature, William Goldman’s 1973 novel The Princess Bride is extremely odd. The book purports to be an abridged edition of a classic adventure story written by someone named Simon Morgenstern. In a bizarre introduction (more about which in a moment), Goldman claims merely to have acted as editor. Unlike Rob Reiner’s much-loved 1987 film adaptation, the book’s full title is The Princess Bride: S. Morgenstern’s Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure, The “Good Parts” Version. Yes, all that text actually appeared on the cover of the book’s first hardcover edition (all but the first three words have been scrubbed from the covers of most subsequent editions).

In the 1990s, I worked at a Tower Books store in Sacramento. Every few months, someone would come into the store and ask if we had an unabridged edition of S. Morgenstern’s The Princess Bride. The first time this happened, a younger colleague who had worked there longer than I had told my customer, “The Princess Bride was written by William Goldman. There is no S. Morgenstern. Goldman made him up.” The customer wasn’t convinced. “It’s metafiction,” my colleague explained. “A novel that comments on its own status as a text.” When the customer had left, my colleague told me that a lot of people still believe there is an original version of the novel available somewhere, written by Morgenstern. Having fallen in love with the story via the Hollywood film, they were now looking for the ur-text.

I don't know who needs to hear this but most of the 1-star Amazon reviews for The Princess Bride by William Goldman are people absolutely IRATE that it isn't "the original book" and is instead an "abridged version" by "the screenplay writer." pic.twitter.com/zwTqx1WIPl

— Lauren Thoman (@LaurenThoman) March 3, 2023

Although I was a big fan of William Goldman, I had never read The Princess Bride. My wife and I saw the film when it first appeared in American theaters, and we have rewatched it several times since on VHS and DVD. Only about 10 years ago did I actually get around to reading the novel. And when I did, I found myself sympathizing with all those people who still believe that, somewhere in the world, there exists an unedited edition.

In his introduction, Goldman tells us that S. Morgenstern was from the tiny European nation of Florin, located somewhere between Germany and Sweden, which is where the story’s action takes place. Such a place never existed, but it’s not surprising that many 21st-century American readers don’t know the names of every current and former European kingdom. European history is littered with microstates that rose briefly and then vanished without leaving much of a trace. Back in the 1990s, before Internet access became commonplace, confirming the existence of a small defunct European statelet would have involved a trip to the library.

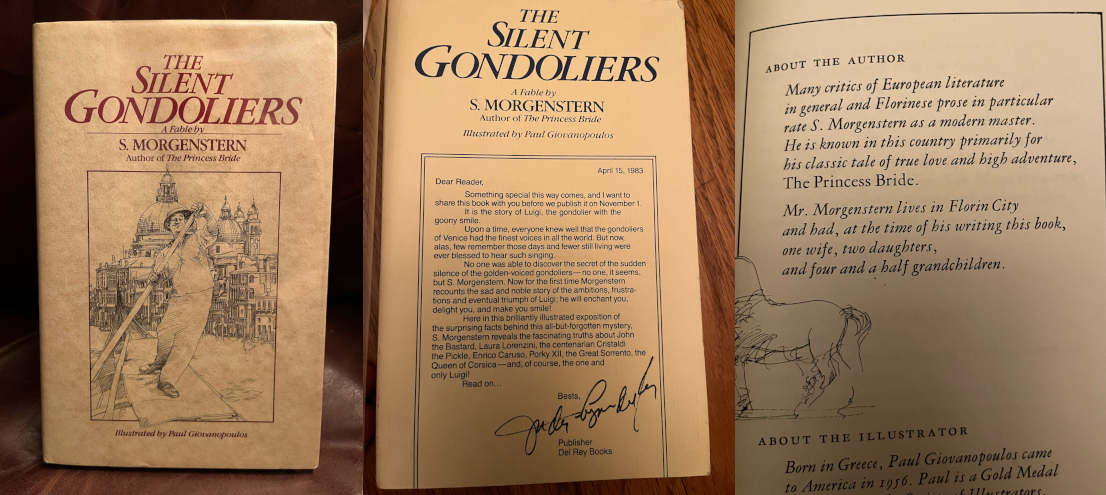

But readers in the 1970s might have been more alive to Goldman’s ruse. Back then, metafiction was all the rage. John Barth became a literary superstar (among the academic set, anyway) with books like The Sot-Weed Factor (which, like The Princess Bride, is a fantastical comic adventure supposedly written by a fictional author) and Giles Goat-Boy (the text of which, Barth writes in the foreword, was said to have been written by a computer). In 1983, Goldman would publish a second novel behind the Morgenstern pseudonym, titled The Silent Gondoliers, but this time he removed all mention of himself, even from the copyright page.

The beginning of The Princess Bride—in which Goldman presents the reader with a chatty, informal introduction to the work and to himself—resembles the opening of Kurt Vonnegut’s metafiction Breakfast of Champions (published the same year). We are told that Goldman’s father migrated to America at 16 and that his English was always very “immigranty.” In 1941, when he was 10, Goldman fell ill with pneumonia. After a short hospital stay, he was sent home to recuperate and spent several weeks in bed. His only real pleasure during his convalescence was listening to sports on the radio. One evening, his father sat down at the end of his bed and began reading to him from S. Morgenstern’s novel The Princess Bride. Prior to this, Goldman hadn’t been much of a reader. But after that night, everything changed:

For the first time in my life, I became actively interested in a book. Me the sports fanatic, me the game freak, me the only ten-year-old in Illinois with a hate on for the alphabet wanted to know what happened next. … Each night my father read to me, chapter by chapter, always fighting to sound the words properly, to nail down the sense. And I lay there, eyes kind of closed, my body slowly beginning the long flow back to strength. It took, as I said, probably a month, and in that time he read The Princess Bride twice to me. … Even today, that’s how I summon back my father when the need arises. Slumped and squinting and halting over words, giving me Morgenstern’s masterpiece as best he could. … My whole life with my father reading me the Morgenstern when I was ten. … That book was the single best thing that happened to me.

We jump forward in time and William Goldman is now an adult, married to a psychiatrist named Helen. They have a son, Jason, and the three of them live together in a nice New York City apartment. Goldman reminisces about the publication, in 1957, of his first novel, The Temple of Gold. Then he tells us, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is, no question, the most popular thing I’ve ever been connected with. When I die, if the Times gives me an obit, it’s going to be because of Butch.” As Jason’s 10th birthday approached, Goldman was out west, staying at the Beverly Hills Hotel, taking meetings with the producers of The Stepford Wives, which Goldman had been hired to adapt from Ira Levin’s novel. Remembering how his life was changed when his father read The Princess Bride to him, Goldman telephones his wife in New York and asks her to track down a copy of Morgenstern’s masterpiece to give to Jason for his birthday.

But then the introduction gets even weirder. Goldman was 40 and had been married for 10 years when he accepted the Stepford Wives assignment. One sunny California day in December, he is out by the hotel pool when “from somewhere, there actually appeared a living, sun-tanned, breathing-deeply, starlet. I’m lolling by the pool and she moves by in a bikini and she is gorgeous. I’m free for the afternoon, I don’t know a soul, so I start playing a game about how can I approach this girl so she won’t laugh out loud. I never do anything, but ogling is great exercise and I am a major-league girl watcher.”

He begins flirting with the young woman and discovers that she is an aspiring actress named Sandy Sterling. He mentions that he is writing the script for The Stepford Wives, and she makes it clear that she would be willing “to do anything for a shot at that.” Unfortunately, his name is paged and he has to answer a telephone call. It is his wife. He snaps at her, telling her that he is in a story conference and that she shouldn’t be interrupting him. Helen informs him that she can’t find a copy of The Princess Bride anywhere. He tells her to call Argosy Books on 59th Street then hurries back to the pool. He thinks of telling Sandy that he doesn’t do the kind of thing she suggested. “But then I figured, Hey wait a minute, what law is there that says you have to be the token puritan of the movie business?” But once again, he is interrupted by a phone call from his wife. Argosy doesn’t have a copy of The Princess Bride, she says. At which point, Goldman snaps at his wife so nastily that she begins to suspect that it isn’t a story conference she is interrupting. They bicker for a while and then Goldman hangs up and returns to Sandy.

As they flirt in the pool together, Goldman decides he’ll try to track down the book himself. The phone is still at poolside, so Sandy waits while Goldman starts calling multiple New York bookstores. Sandy gets bored and departs. Goldman tells us that his efforts to make Jason happy cost roughly 120 minutes of long-distance calls at a rate of $1.35 per minute. The tediousness of this detail somehow adds to the story’s believability (today, I can go to Wikipedia and discover that Goldman’s wife was named Ilene and that their two children were both girls). Goldman telephones his real-life attorney and then his real-life editor at Harcourt Brace and Jovanovich and tries to enlist their help in tracking down a copy of a book that doesn’t actually exist yet. Eventually, he learns that Harcourt Brace and Jovanovich published an English-language translation of The Princess Bride shortly after World War I, when the company was “[j]ust plain old Harcourt, Brace period.”

Weeks pass, and Goldman returns to his New York apartment where he and Helen engage in a tiresome discussion about how difficult it is to find good domestic servants in New York. Helen seems to sack each new cook she hires after a week or two, all of whom are either “black or Spanish.” She hopes that won’t be the case with Angelica, the latest cook, whom Goldman hasn’t seen yet. When Goldman sits down to dinner, he finds that, “My pot-roast slice was not terribly moist but the gravy could compensate. Helen rang. Angelica appeared. Maybe twenty or eighteen, swarthy, slow-moving.” Helen scolds the poor girl: “Now, Angelica, there is no problem and I should have told you more than once about Mr. Goldman’s preferences, but next time we have boned rib roast, let’s all do our best to make the middle pink, shall we?” After which, Goldman tells us, “Angelica backed into the kitchen. Another ‘treasure’ down the tubes.”

Then, after Angelica backs out of the room, Goldman sets about fat-shaming his fictional son:

Jason was piling the mashed potatoes on his plate with a practiced and steady motion.

I smiled at my kid. “Hey,” I tried, “let’s go a little easy, huh, fella?”

He spattered another fat spoonful on his plate.

“Jason, they’re just loaded,” I said then.

“I’m really hungry, Dad,” he said, not looking at me.

“Fill up on the meat then, why don’t you?” I said. “Eat all the meat you want, I won’t say a word.”

“I’m not eating nothin’!” Jason said, and he shoved his plate away and folded his arms and stared off into space.

“If I were a furniture salesperson,” Helen said to me, “or perhaps a teller in a bank, I could understand; but how can you have spent all these years married to a psychiatrist and talk like that? You’re out of the Dark Ages, Willy.”

“Helen, the boy is overweight. All I suggested was he might leave a few potatoes for the rest of the world and stuff on this lovely prime pot roast your treasure has whipped up for my triumphant return.”

This fight goes on and on, like some grim scene from a dysfunctional-family film such as The Great Santini or Ordinary People (which was directed by the Sundance Kid himself). At one point, Goldman says, “You’re making a poof out of that kid,” which actually sounds like something Robert Duvall might have said in Santini. He also manages to insult both fat people and the Japanese, when he says of his son, “paint him yellow, he’d mop up for the school sumo team. A blimp. All the time stuffing his face.” While Helen is defending her son, Goldman writes, “Sandy Sterling in her bikini was dancing behind my eyes.”

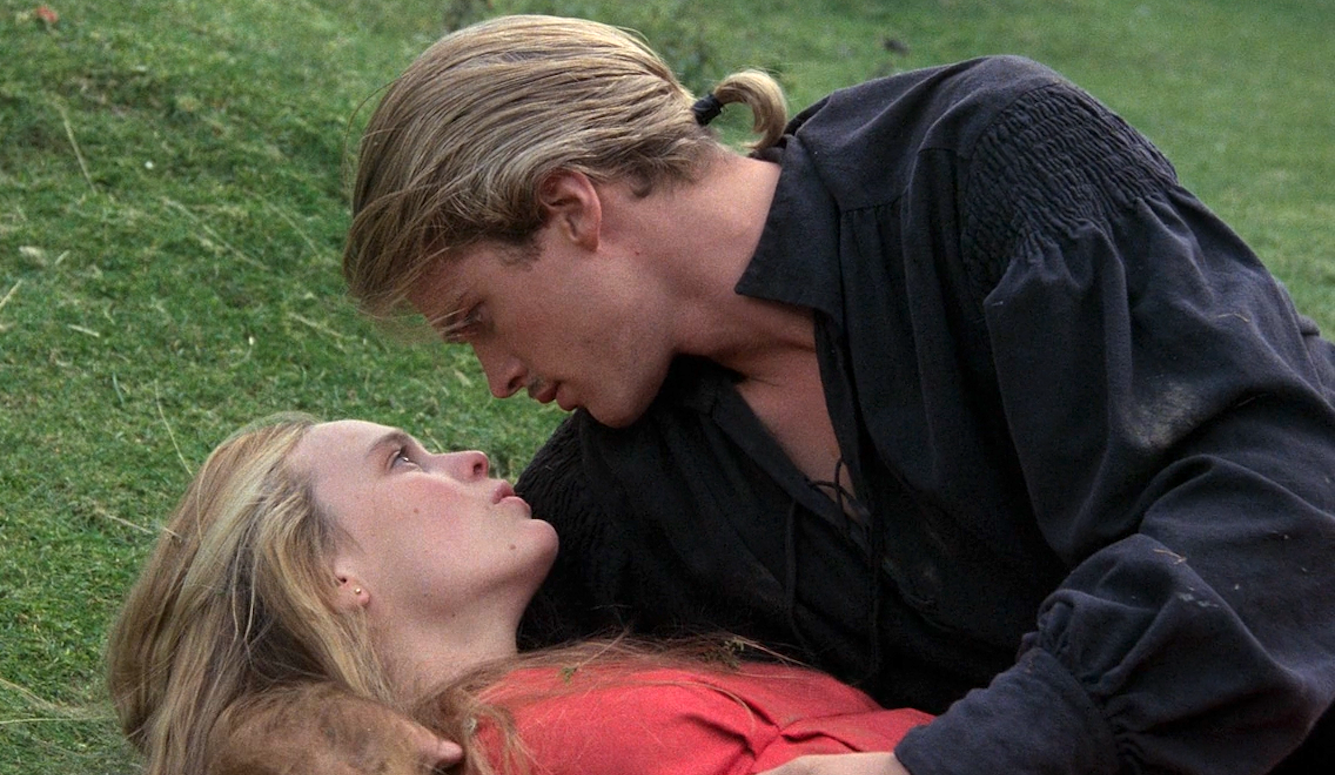

When at last we reach the end of the introduction, we arrive at the book’s first chapter, which is called “The Bride.” We are introduced to a lowly milkmaid named Buttercup and Westley the farm boy in much the same way as they are introduced in the film. After Buttercup declares her love for him, Westley hastens away to America to make his fortune, knowing that this is the only way he can win the approval of Buttercup’s father. Alas, months later, Buttercup learns that the ship taking Westley to America was attacked by pirates who (it is said) killed everyone on board.

Although we have left the introduction behind, Goldman’s commentary continues, set in italics to distinguish them from S. Morgenstern’s words. At times, The Princess Bride seems to exist primarily to promote Goldman’s other work. His first editorial interjection mentions Denise, an HB&J copy editor who has “done all my books since Boys and Girls Together” (which, by the way, was Sandy Sterling’s favorite). In the original hardbound edition, the editorial interjections are printed in red ink, but copies now cost several thousand dollars, so I have never seen one. The original Ballantine paperback edition also displayed the interjections in red, but that edition was pulled from circulation within weeks of its release because of objections over its racy cover illustration. (You can learn more about the various editions of the book here.)

The second chapter, “The Groom,” begins with another of Goldman’s intrusions. He informs us that, in the original Florinese, the chapter opens with a 66-page synopsis of Florin’s history. Mercifully, Goldman junked this material, which reduces the chapter to just three pages. It introduces Prince Humperdinck, the heir to the throne of Florin, who has decided he will marry Buttercup. His sole joy in life is killing animals, and to this end, he has built a five-level, underground Zoo of Death, in which he fights and kills a different beast each day. On this particular day, he spends hours engaged in hand-to-hand combat with some sort of simian (referred to variously as an ape, a monkey, and an orangutan), squeezing its windpipe and trying to suffocate it (“…the ape was heaving at the chest now, desperate for air”). Finally, the Prince breaks its neck.

Reminiscing about the film version of The Princess Bride in his 2000 memoir Which Lie Did I Tell?, Goldman laments that, for “budgetary reasons,” the Zoo of Death had to be replaced by a Pit of Despair. But it seems at least as likely that Rob Reiner had decided to refashion Goldman’s novel as a postmodern family film, and that parents and their young children probably wouldn’t want to watch animals being brutally murdered for sport by a sadistic autocrat. (Humperdinck weighs 250 pounds and is shaped like a barrel in the book, but he is played by the slender and handsome Chris Sarandon in the film.)

Not until Chapter Five, “The Announcement,” does Goldman’s novel truly hit its stride. Not coincidentally, this is the first chapter in which the tone of the prose most closely matches that of the film. Early on, when it appears that Buttercup is about to be eaten by sharks, Goldman employs a different kind of intrusion. It is similar to the film’s framing device, where the story of The Princess Bride is narrated by a grandfather (Peter Falk) to his grandson (Fred Savage), who is home from school, sick, and confined to his bed. Here is Goldman’s intrusion (italics in the original):

“She does not get eaten by sharks at this time,” my father said.

I looked at him. “What?”

“You looked like you were getting too involved and bothered so I thought I would let you relax.”

“Oh, for Pete’s sake,” I said, “you’d think I was a baby or something. What kind of stuff is that?” I really sounded put out, but I’ll tell you the truth: I was getting a little too involved, and I was glad he told me. I mean, when you’re a kid, you don’t think, Well, since the book’s called The Princess Bride and since we’re barely into it, obviously the author’s not about to make shark kibble out of his leading lady. You get hooked on things when you’re a youngster; so to any youngsters reading, I’ll simply repeat my father’s words since they worked to soothe me: “She does not get eaten by the sharks at this time.”

Chapter Five also introduces us to three of the most memorable characters in the story. At first, they are described merely as the Sicilian, the Spaniard, and the Turk. Eventually, we will discover their names. The Sicilian is a self-proclaimed intellectual giant named Vizzini (played by Wallace Shawn in the film); the Spaniard, Inigo Montoya (Mandy Patinkin), is a brilliant swordsman on a years-long quest to find the six-fingered man who murdered his father; and the Turk is Fezzik (André the Giant), a massive but kindly and slow-witted professional wrestler. Almost all of the most memorable lines in the movie come from Chapter Five, and most of them were lifted verbatim from the novel. Chapter Five, by itself, is probably the best piece of prose fiction Goldman ever wrote. It’s a long chapter and could practically stand alone as a classic fairytale in and of itself.

In the final decades of his life, Goldman told just about anyone who would listen that he wrote only two things in his long career, “not that I’m proud of, but that I can look at without humiliation.” These were the original screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and The Princess Bride novel. Goldman sells himself short here. At least three of his other screenplays (All the President’s Men, Misery, and The Princess Bride) are masterful. And his 1974 novel, Marathon Man, was one of the best thrillers of the 1970s. But if Butch and Bride were, in fact, his two best works, Chapter Five brings the two of them together in many ways.

Butch is essentially one long chase, wherein a posse doggedly pursues the titular outlaws across hundreds of miles of Western terrain. Again and again, Butch and Sundance look back at the men pursuing them and wonder, “Who are those guys?” In Chapter Five of Bride, Vizzini, Montoya, and Fezzik, who are attempting to kidnap Buttercup, are pursued by a man in black who seems to be constantly gaining on them. Over and over again they wonder, Who is he? In Butch, the posse’s tracker possesses an unnatural ability to trace his quarry. In Bride, there is a long scene (a shortened version of which appears in the movie) in which Humperdinck recreates an entire sword fight simply by looking at the footprints on the ground.

In Butch, the two outlaws find themselves stymied near the top of a sheer cliff. In Bride, the three kidnappers find themselves stymied, briefly, at the base of the Cliffs of Insanity. When they finally make it to the top of the cliff, they look down and see the man in black climbing towards them. Vizzini feels certain the man will fall, and tells the others, “[H]e will be dead long before he hits the water. The fall will do it, not the crash.” In his introduction to Bride, Goldman tells us that the most famous scene in Butch is “the jump off the cliff.” Sundance tells Butch he can’t swim. “Are you crazy?” Butch laughs. “The fall will probably kill you!” The line is so iconic that it has been copied in other pop cultural products. In his introduction, Goldman claims it was the Cliffs of Insanity in Morgenstern’s book that inspired the scene in Butch. Clearly, it was the other way around.

Further parallels abound. Both feature a giant who is defeated by the hero in a fistfight. Both feature a character who dresses in black and possesses an uncanny amount of skill with his preferred weapon. Both stories feature an ornamental female character/love interest. And both Butch and Bride (the novel) end with the protagonists facing almost certain destruction by their enemies. The two stories seem to be funhouse-mirror images of one another.

Reiner’s movie is probably better than Goldman’s book, but Chapter Five of the book is better than the corresponding scenes in the film, because backstory is much easier to establish in a novel. Chapter Five brings Inigo Montoya’s father, Domingo, alive for us in a way that the film never even attempts. It also gives us Fezzik’s backstory: his birth, his childhood, his kindly parents, his long career as a globetrotting professional wrestler hated by audiences because of his invincibility in the ring. And it tells us much more about the relationship between Westley and the Dread Pirate Roberts.

After Chapter Five, the novel takes some extremely dark turns. Traditional children’s literature is full of horrors, of course, but the latter half of The Princess Bride presents a good deal of torture as entertainment for the reader. Some of these scenes occur in Buttercup’s nightmares, where she imagines giving birth to Humperdinck’s child only to have it die in some hideous fashion right before her eyes. As in the film (where he is played memorably by Christopher Guest), Count Rugen, Humperdinck’s six-fingered right-hand man, is an authority on torture. In the book, he is writing a treatise on pain, and he researches it by torturing animal and human subjects.

Rugen sets Westley’s hands on fire in one scene. In another, he unleashes insects known as Spinning Ticks, which screw themselves into the flesh and have to be burned out. As in the film, Rugen invents a machine for inflicting pain on living creatures. In one of the book’s most disturbing scenes, he straps an animal into it; a trial run for the torture he will later inflict on Westley:

Yellin [Florin’s chief law-enforcement officer] had heard many things in his life but nothing quite so eerie as this: he was a brave man, but this sound frightened him. It was not human, but he could not guess the throat of the beast it came from. (It was actually a wild dog, on the first level of the Zoo, but no wild dog had ever shrieked like that before. But then, no wild dog had ever been put in the Machine.) The sound grew in anguish. … It would not stop. It simply hung now below the sky, an audible reminder of the existence of agony. In the Great Square, half a dozen children screamed back at the night, trying to blot out the sound. Some wept, some only ran for home.

Among his many other writerly gifts, Goldman was an expert at dreaming up exquisite torture (the dentistry drill scene in John Schlesinger’s 1976 adaptation of Marathon Man became particularly notorious). It’s nevertheless curious that he gave this gift its fullest expression in what was (ostensibly, at least) a children’s fairytale.

Throughout the 1970s, various directors—including Robert Redford, François Truffaut, Richard Lester, and Norman Jewison—became interested in filming The Princess Bride but were unable to secure studio backing. I suspect that the enormous interest in the 1981 royal wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer helped convince Twentieth Century Fox to greenlight the film. The stars of the film, Cary Elwes (born 1962) and Robin Wright (1966), were, like Lady Di (1961), part of the late-Boomer early-Gen-X birth cohort. The film was shot in England and its look tends to mimic British fantasy tales rather than Germanic ones.

But if this resonance was intended to produce box office gold, Fox were to be disappointed. During its initial theatrical run, Bride earned $31 million on a production budget of $16 million. Once you account for its advertising costs, the film probably wasn’t especially profitable. In his foreword to Cary Elwes’s 2014 memoir, As You Wish: Inconceivable Tales from the Making of The Princess Bride, Rob Reiner writes, “We opened to some critical success but only moderate business. Luckily through VHS, DVD, and TV it managed to take hold, and over the past twenty-five years its popularity has grown.”

Like Groundhog Day, the film’s modest box-office earnings do not reflect its massive cultural influence. Millions of Boomers and Gen-Xers can recite lines from memory, which suggests that most of them absorbed its dialog from multiple VHS viewings rather than a single theater experience. Elwes notes that for a year or so after the film’s original release, he rarely heard anyone mention it. It seemed to be mostly dead.

And then—I can’t pinpoint the time when it actually occurred—a strange thing began to happen: The Princess Bride came back to life. Much of this can be attributed to timing—in particular to the newly developing video market. The Princess Bride came to be enormously popular in VHS format. And it was via this relatively new medium that the film began to gain traction, and not simply as a rental. After careful scrutiny by those who do these things, it became clear that fans were not only recommending it to friends and family members, they also began purchasing a copy for their own home libraries. Copies of it were being passed down from generation to generation in much the same manner that children were introduced to the magic of The Wizard of Oz by nostalgic parents who wanted to share one of their favorite movies.

In the late 1990s, for a 25th-anniversary edition of The Princess Bride, Goldman added two things to the end of novel that made it even weirder, and not in a good way. One of these additions is the first chapter of a sequel that Morgenstern supposedly wrote, titled Buttercup’s Baby: S. Morgenstern’s Glorious Examination of Courage Matched Against the Death of the Heart. But before that, we get another long (25-page) authorial intrusion in which, among a lot of other nonsense, Goldman explains that the trustees of the estate of S. Morgenstern have decided to hire Stephen King to write the abridgement of Buttercup’s Baby. After that, Goldman flies to Bangor, Maine, for a meeting with King and the whole thing just becomes way too meta for its own good. The joke about Goldman not having been the real author of The Princess Bride was never that funny to begin with. By 1998, he had beaten it thoroughly to death.