Nations of Canada

John Cabot’s New Found Land

In the fourth instalment of an ongoing Quillette series, historian Greg Koabel describes how the quest for cod and a possible passage to China sparked England’s first transatlantic ventures

What follows is the fourth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialized project adapted from transcripts of Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name, which began airing in 2020.

The European “voyages of discovery” in the late 15th and 16th centuries have long been derided as poorly named. The lands they encountered may have been new to them, but they certainly weren’t new to their indigenous residents. That criticism is especially true of the voyages to the eastern coast of Canada in the 1490s and 1500s. Not only were these lands already populated, but they had already been visited by Europeans several hundred years earlier. In the case of Greenland, the Portuguese bragged about discovering it around 50 years after the Norse left. The English managed to top that by claiming to have discovered Greenland again a few decades later.

I start with this little aside, not to mock the early explorers of Canada’s Atlantic coast, but to draw in our earlier visit with the Norse—because the links between the voyages of Leif Erikson and those we’ll cover below are more direct than the 500 years of distance between them would suggest.

Although the Norse retreated from Newfoundland in the 11th century, they would remain a presence in the North Atlantic and the Canadian arctic for several centuries. And it was this same North Atlantic world that drove European, and especially English, interest in westward exploration.

So we’re going to start with the North Atlantic Norse in the 15th century.

As you know from our previous instalment on The World of the Iroquois, a lot was happening around the 1450s. The Iroquois and Wendat Confederacies were forming around the Great Lakes while the Norse were pulling out of Greenland. In part, the abandonment of Greenland was sparked by the cooling of the climate, which made livestock farming difficult. But for Norse Eastern Settlement, which had held on into the mid-15th century, economic factors were far more important.

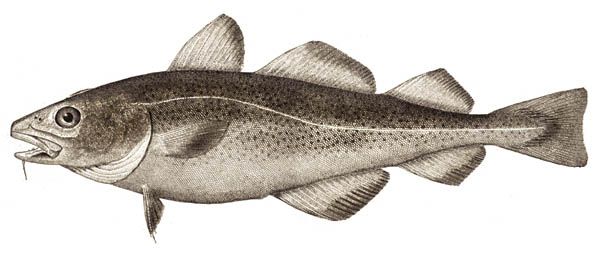

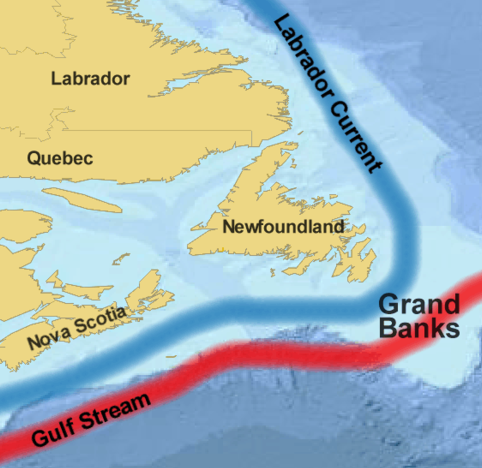

To be specific, a fishing boom was turning the North Atlantic into a competitive, at times dangerous, place. At the centre of it all was cod, a staple of the early modern European diet. Cod could be found in massive numbers in the North Atlantic. In fact, the migration path of the medieval Norse, from Iceland, to Greenland, to Newfoundland, maps quite well onto the distribution of cod, suggesting that fish was an important source of food for these travellers.

For much of the medieval period, the North Atlantic cod mostly served a local market. Other fish, such as herring, were plentiful in the North Sea and Baltic, and there was not much incentive to harvest and preserve cod on a large scale for the purpose of export. That began to change, however, as Europe’s population recovered after the devastation of the Black Death in the mid-14th century.

Cod was particularly well suited to address the growing demand for food because it could be efficiently preserved. The cod is not a particularly fatty fish. So, if properly dried and salted, it can go a long time before spoiling. In a world without refrigerators, that was a rare quality. (Herring can also be preserved by salting or pickling, but due to its high fat content, the process is more costly.)

As a result, cod became a mainstay in regional cuisines all across Europe. It was cheap, plentiful, and easy to ship. All you had to do was re-hydrate in water, and serve: a kind of 15th century cup-o-noodles. By the 16th century, around 60 percent of all fish being eaten in Europe was North Atlantic cod.

But where valuable commodities emerge, geopolitical tensions almost inevitably follow. During the 15th century, Iceland was the focal point for an international commercial struggle. The main players were the joint Danish/Norwegian Crown (which had taken control of Iceland when the commonwealth there collapsed into rival chieftains); the Hanseatic League (an international conglomerate of German merchants who wielded tremendous influence in Iceland); and English fishermen looking to exploit the seas of the North Atlantic.

The Hanseatic League had successfully cornered the market on herring in the Baltic Sea, and were looking to repeat the trick with the even more lucrative cod market in the North Atlantic. The Danish kings welcomed this as a way to turn their distant protectorate into a profit-making enterprise. And so the Danes commissioned German agents to supervise the operation in Iceland. It quickly became apparent that their number one priority was keeping competitors out. And more than anyone else, that meant the English.

Of course, there were other European fishermen looking to cash in on the cod boom, too. The Basques had been trawling the open ocean for centuries, and the growing market for salt cod was now attracting Portuguese, French, and Breton fishermen, too. (At this point, Brittany had not yet been absorbed into the kingdom of France). But each of these nations had something the English didn’t—easy access to salt. Large scale salt deposits just didn’t exist north of the English Channel.

This was a major disadvantage in the cod game, because in order to make your voyage worthwhile you had to be preserving your catch as you sailed. Basque and French fishermen (with their mountains of salt) could do this easily enough on board their ships. But the English technique (a light salting and a lengthy dry in the sun) required a base on land. England itself was too far from the cod for such purposes—and this is where the fractious relationship with Iceland came in.

English ships (mostly out of the western port of Bristol) were frequent visitors to Iceland—either bringing merchants looking to buy salt cod, or fishermen looking to process their catch in seasonal camps. This inevitably sparked commercial disputes with the Germans, and Danish complaints about the violation of territorial sovereignty. As this was the 15th century (long before the creation of the World Trade Organisation, needless to say), commercial disputes could get quite violent. From 1415 to 1425, a state of quasi-war existed between English fishermen and Icelandic authorities, until locals were intimidated into accepting a seasonal English presence.

But the truce did not hold for long. Throughout the 15th century, the English faced off against the Germans and Danish in a series of conflicts known as the Cod Wars. (The last of these battles took place in mid-1970s, making it one of the longest running commercial disputes in history.)

As we’ve seen earlier, the North Atlantic morphing into a war zone was bad news for the struggling Norse settlement in Greenland. It’s possible that English fishermen even raided the settlement at one point, which likely contributed to the decision to close up shop. Certainly the frequent raids on shipping played havoc with life in Greenland, as residents were so dependent on imports.

The year 1475 appears to have been a turning point in this conflict (though, sadly, one that came too late for the Greenland Norse, who had disappeared from history about 20 years earlier). In 1475, the Danish Crown appointed a new governor of Iceland, a German named Didrik Pining. Pining arrived with a mandate to expel the English merchants and fishermen from Icelandic waters once and for all. By 1478, he had succeeded. Although this was not the end of the Cod Wars by a long shot, English ships were effectively barred from the region for a number of years.

The reason we care about this turning point is because it was not just a turning point in Anglo-Icelandic relations, but also one in world history. The merchants and fishermen of Bristol decided that engaging in perpetual war was no way to run a profitable business. If they wanted to make money from cod, they’d have to find some other place to dry their fish.

Luckily, a local Bristol legend suggested an alternative. There was an old wives’ tale that had been making the rounds for years that a ship out of Bristol had once been blown way off course, deep into the ocean. Lost and far from home, the crew was fortunate enough to sight land. Unsure of where they were exactly, they fixed up their ship, and headed home. (It’s unlikely that this actually happened. The story probably grew out of the old Gaelic legend of Hy-Brasil, a mysterious phantom island west of Ireland that periodically appeared and disappeared.)

It’s also possible that the Bristol mariners who had been going to Iceland for around 80 years by this point had picked up bits and pieces of information about the Norse voyages of the 11th century. After all, many Icelandic locals were more than happy to trade and fraternize with the Bristolians. The primary source of English conflict was with their German competitors and the Danish Crown. In fact, records indicate that as many as 50 Icelanders were living in Bristol during this period—including a naturalized English subject with the (likely anglicized) name of William Ysland.

Markland (the Norse name for Labrador) appeared to be common knowledge in Iceland as late as the 1350s. So it’s plausible that through contact with Icelanders, the Bristolian had heard of the lands to the west, which breathed new life into the old Gaelic legends.

In 1480 and 1481, a handful of Bristol investors funded multiple voyages, though the details of which are frustratingly opaque in the historical record. Part of this was likely intentional: In the competitive world of the North Atlantic cod fisheries, there was no upside to advertising new fishing grounds. In fact, the Basques had long been notorious for keeping their open-sea fishing grounds a secret.

We’ll likely never know for sure, but it’s possible (if not quite bordering on likely) that the men of Bristol had found the fantastically bountiful Grand Banks fishery off the coast of Newfoundland.

Whatever they found, word quickly spread among the other cod fishing nations of western Europe. The Portuguese, who were making rapid navigational headway down the coast of Africa, suddenly turned their attention to the North Atlantic, too. Their recently established colony in the Azores, deep in the Atlantic, gave them a great base to operate from.

But the secretive world of 15th century corporate espionage isn’t the only reason this chapter of history is shrouded in intrigue. This is one of those rare occasions when the historians themselves become part of the story.

What should have been the definitive book on Bristol’s voyages of discovery at the end of the 15th century never got written. The writer of this non-existent book was Alwyn Ruddock (1916–2005), a leading British historian on the topic of Italian banking families operating in England during the so-called Age of Discovery. As you might have guessed from her area of expertise, Ruddock approached the English voyages of discovery from the perspective of the financiers who backed them, many of them being members of the great Italian baking families whose networks stretched across Europe. As a result, Ruddock came across material in Italian archives that Anglo-centric historians had not encountered before.

Or, at least, we think she did. The problem is that Ruddock died in 2005, and in her will she requested that the research notes for her long-awaited book be destroyed. Whatever her reasons, Ruddock’s decision leaves us with a tantalizing mystery. What exactly had she uncovered?

While still working on the book, Ruddock shared some of her work with David Beers Quinn (1909–2002), another leading historian who wrote about the European voyages of discovery. Quinn claimed that the book was “so revolutionary and so extensively based on new documents that it will change the whole course of the Cabot celebrations of 1997” (referring to the 500-year anniversary of John Cabot’s “discovery” of Canada while sailing under the English flag).

We don’t know exactly what material Ruddock was working on, but the various hints she gave about her book have spurred subsequent historians to piece together at least some of what was lost. The result has a been a resurgent interest among historians in Bristol during the 1480s and 1490s.

One previously obscure figure that has captured the interest of these historians is William Weston, whose story I will now tell at some length, for reasons that (eventually) will become apparent.

Weston first makes an appearance in the historical record in the late 1460s, as his name appears in the Bristol customs rolls (the documentation of the import and export taxes paid by international merchants). Weston was likely a young man at this point, probably in his mid-20s, acting as a “factor” or agent for well established Bristol merchants. His job was to travel on ships carrying goods overseas, and represent the owner when the transaction was completed in some foreign port. This was a position of responsibility, usually entrusted to young men on the rise in Bristol’s mercantile community.

While Weston made at least a few trips to Bordeaux and Seville, he specialized in trade with the Portuguese at Lisbon. Primarily, this meant the export of English cloth, and the import of wine and salt. Bristol’s competitors in Brittany and France tended to carefully guard their strategically important salt reserves, so the English relied heavily on Portuguese salt to fuel their cod processing.

Weston continued this work through the 1470s, and at a certain point started working exclusively on a ship named the Trinity. The Trinity was owned by John Foster, one of the wealthiest men in Bristol. Foster was a big player in the Icelandic trade, but had his fingers in just about every pie there was. When Iceland closed its ports to English ships in 1478, Foster began using the Trinity (and, with it, William Weston) to look for new opportunities further afield.

In 1481, the Trinity was one of the ships used to search for the legendary island of Hy-Brasil in the western Atlantic. But that wasn’t the only place Foster sent out his feelers. The year before, the Trinity had made a voyage to Oran in North Africa (a rare and dangerous trip for an English ship). Merchants from Bristol had made attempts to crack the Mediterranean market before, but these usually ended poorly. (Most notorious was a voyage in the 1450s that was cut short by Italian pirates.)

In 1480, Weston travelled on a Breton ship to Madeira, situated north of the Canary Islands and west of Morocco—one of Portugal’s Atlantic island colonies. As far as we know, he was the first Englishman to set foot there. Likely, he was looking to use his connections in Lisbon to establish a direct commercial relationship with the sugar plantations of Madeira. Sugar was one of the hot commodities in Lisbon, but Weston figured he could get it cheaper at its source.

So by the early 1480s, William Weston was associated with some of the top merchants in Bristol, who were looking to expand and diversify their trade.

This culminated in 1483 with the construction of the Anthony, which immediately became the largest ship in Bristol’s merchant fleet. John Foster was one of its major investors, and William Weston acted as the owners’ eyes and ears on board. One of the perks Weston enjoyed in his post was the right to use some of the Anthony’s cargo space for his own private trading. Through his regular voyages to Lisbon, he was well on his way to entering the ranks of the Bristol mercantile elite. He was even courting Foster’s daughter, Agnes.

In September 1487, the Anthony set out on its biggest run yet. In its hold it carried around five percent of all the cloth that would be exported from Bristol that year. Weston, by now an established man in Lisbon, supervised the transaction without incident over the winter. But at the very end of the return voyage, with Bristol almost in sight, disaster struck. On February 25th, 1488, the Anthony sank just 10 kilometers from harbour. Weston managed to get to shore, but all the ship’s cargo was lost. Bristol’s biggest transaction of the year had been erased.

The sinking of the Anthony ruined Weston’s once promising career, and set off a lengthy legal wrangle. Weston’s private trading on the voyage had been financed through a loan from a fellow Bristolian, Thomas Smith. One of the conditions of the loan had been that if the ship was lost on the voyage, Weston would not have to pay the money back. Weston pointed to where the Anthony sat at the bottom of the sea and argued that he was free from any debt. But Smith had a stronger case than it appeared: The Anthony had sunk in the treacherous approaches to Bristol’s harbour. Legally speaking, it had arrived home, its voyage complete.

The dispute bounced around the courts for years, but over time it became apparent that Weston had the losing argument. His strategy increasingly focused on delay rather than victory.

Things were hardly better for Weston outside of court. Although the captain was determined to be officially responsible for the accident, the Anthony’s investors blamed Weston. As the representative of the owners, Weston had a responsibility to ensure everything went smoothly. The relationship between John Foster and William Weston (who had been business associates for almost two decades at this point) turned particularly sour. This was especially problematic because by this time Weston had married Foster’s daughter. So the great man of Bristol wasn’t just his boss, but also his father-in-law.

After 1488, Weston’s name largely disappears from the Bristol customs rolls. His notorious reputation among the great merchants of the city likely barred him from representing anyone in Lisbon.

Weston’s tenuous position was dealt a further blow when Foster died in 1492. Not only did the old man write his son-in-law out of his will, but he virtually disinherited his daughter as well. In fact, the one thing he left to Agnes (his fashionable mansion on Corn Street) was a poisoned chalice. Foster granted the house for Agnes’s lifetime only (her children with Weston would not inherit it). But more problematic was the fact that, connected to the property, was an alms house—a charity Foster had established to care for the poor. The Westons were now responsible for funding the alms house, and if they failed to do so they would be immediately evicted from the property. These conditions were impossible for Weston to fulfill, and he entered into yet another legal quagmire.

Now, at this point you might be thinking, this is all good fun, but what does a failing merchant in Bristol have to do with the history of Canada?

The important thing to note here are the qualities William Weston possessed. He was an experienced and well travelled sea-farer, with a desperate need for a big break: the perfect candidate for a long-shot gamble into the unknown. And in the 1490s Weston met a kindred spirit who had just moved to Bristol: another failed merchant desperate enough to try anything.

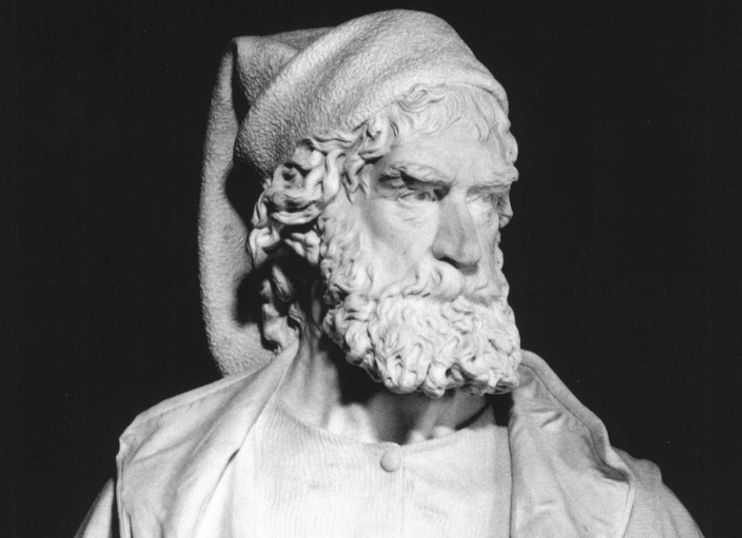

The second character in our drama was born Giovanni Caboto in the Italian city-state of Genoa around 1450—roughly the same time as another famous Genoan, Christopher Columbus). In fact, Caboto and Columbus would cross each other’s paths multiple times.

As a child, Caboto moved with his family to Venice, where he grew up within the city’s merchant community. As a young man, he travelled extensively in the Eastern Mediterranean, likely engaging in work similar to that of the young William Weston. Caboto’s early career wasn’t marked by anything quite as dramatic as Weston’s disaster. But, coincidentally enough, the nadir of his life as a Venetian merchant came in the same year as the sinking of the Anthony—1488.

That year, Caboto’s debts forced him to flee Venice. He soon popped up in Spain (around the same time his fellow Genoan, Christopher Columbus, was lobbying the Spanish Crown to support his voyage to the Indies). In 1492, Caboto started a job working with the civil authorities in Valencia, on Spain’s Mediterranean coast. He acted as an advisor on the improvements being made to the city’s harbour, and was still there in 1493, when Columbus passed through Valencia, fresh off the triumph of his first voyage across the Atlantic.

Soon after, Caboto decided to move across Spain to Seville, the launching pad for Spain’s emerging Atlantic ambitions. He had dreams of matching, or even surpassing, Columbus’s achievements. He may also have had more immediate motivations, as his Venetian creditors had started poking around Valencia, threatening his job with the local government there.

In Seville, Caboto once again joined a civil engineering project, this time the building of a bridge over the Guadalquivir, the river connecting the city to the ocean. In his free time, he lobbied the Spanish Crown to back his plans for westward exploration. Caboto saw right away that Columbus had not in fact discovered a back door to China. He urged the Spanish to let him try out a different route.

The Spanish, however, were happy with Columbus’s work, and devoted their resources to following up on his initial voyage. Frustrated, Caboto moved on to Portugal, arriving in Lisbon in 1494. There, he once again failed to convince the powers that be: The Portuguese were focusing their efforts on approaching the Indies via Africa.

In fact, just as Caboto arrived in Lisbon, the Portuguese were finalizing the Treaty of Tordesillas with their Spanish neighbours. The agreement divided the globe between the two exploring powers. The new lands on the other side of the Atlantic were Spanish; those to the east, along the African coast and beyond, were Portuguese. Caboto’s plan for a voyage into the Atlantic might cause exactly the kind of conflict with the Spanish that Portugal was hoping to avoid with the treaty.

Caboto’s dreams of wealth and fame seemed as unlikely as ever. And it appeared he was destined to be just another failed Venetian merchant.

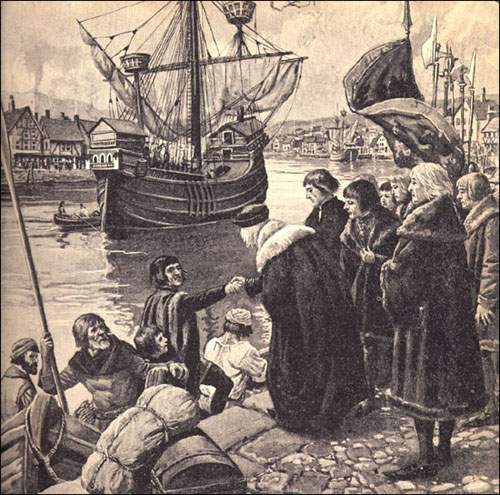

But one group in Lisbon was intrigued by the rumours of an energetic Italian, bragging about his ability to discover new lands. This group was the colony of English merchants permanently based in Lisbon (most of them associated with businessmen in Bristol).

By this point, fishermen out of Bristol had been ranging far out into the Atlantic for more than 10 years. If there really were new lands out there, the Bristolians would be the ones to know. The fishermen had an incentive to keep such information under wraps, but Columbus had changed the arithmetic. What if there weren’t just fish out there, but a whole continent full of valuable commodities?

Caboto seized on this interest as the first positive response his plans had yet received—though he also had reason to think the English were a better alternative than the Spanish or the Portuguese in any case. Just as with modern airline routes, Caboto recognized that crossing the globe near the equator, as Columbus had done, yielded a much longer trip than travelling closer to one of the poles. And so Caboto was banking on the northern kingdom of England providing a shorter route to the Orient. He immediately packed his bags and headed for England.

Giovanni Caboto’s move to England, where he would become “John Cabot,” is one of the elements of the story that Alwyn Ruddock’s research has shed new light on. Previously, we assumed Cabot headed straight for Bristol, the base of his future explorations, and the place where his family would eventually reside. But in fact, he first headed to London.

We know this from the records of the Italian banking houses that had offices in London, which is where Cabot headed. His experience in Spain and Portugal had taught him that monarchs were more than willing to offer potentially lucrative concessions, such as monopoly trading rights in newly discovered lands; but they were stingier when it came to footing the bill for start-up costs.

Cabot’s English friends warned him that this was doubly true of England’s King, the founder of the Tudor dynasty, Henry VII. Henry, who had seized the Crown through conquest just a few years previously, in 1485, was notoriously thrifty. Historian S.T. Bindoff has described him as “the best businessman to ever sit upon the English throne.” Which meant he was open to the commercial benefits of exploration, but he would not be duped into investing in a long-shot gamble.

Caboto therefore turned to London-based Italian bankers for financing. He found a willing partner in Giovanni Antonio Carbonaro, an Italian monk in the Augustinian Order who was a major player at court. Carbonaro served double duty as diplomatic envoy from the Duchy of Milan and a tax collector for the Pope. (England after all, would remain faithful to the Catholic Church until Henry’s son, Henry VIII, changed things.)

Carbonaro’s interest in exploration was driven by reports from the missionaries who’d joined Columbus on his second voyage (which was still ongoing when Cabot arrived in England). Carbonaro imagined himself as the architect of a religious mission to China that might be possible if Cabot found a more direct route to the east.

The monk proved to be a valuable ally, as he was able to usher Cabot into the upper echelons of the Italian banking community. With Carbonaro behind Cabot, the financiers were willing to look past his spotty credit history back in Venice. Taking the lead was the Bardi family, a banking conglomerate with its headquarters in Florence. Enough money was duly raised to finance a small-scale voyage.

Next, Carbonaro brought Cabot to Henry VII’s court. While they didn’t need the King to foot the bill for the project, his blessing was required if the voyage were to be profitable. Cabot’s investors were banking on him creating a lucrative trade route, not just going on a one-time trip. Ideally, the King would reward Cabot with a monopoly on all English trade with the new lands he discovered. This would provide the real return on investment.

Secondly, Cabot needed diplomatic cover for his project. All indications were that Spain and Portugal were serious about enforcing the Treaty of Tordesillas. That meant that the Spanish Crown would regard any unlicensed traders or explorers in the Western Hemisphere as criminals. If Cabot’s trip was going to work, he needed a royal backer of his own, so as to stand up to any potential Spanish opposition.

I realize that much of this may feel far afield from goings on in Canada. But making sense of the narrative surrounding Cabot requires us to at least briefly get into European power politics. As mentioned earlier, Henry (more than any other English king of his era) had a keen eye for commerce. He saw trade as an instrument to rebuild England’s wealth and stability after the destructive Wars of the Roses. In fact, in the first year of his reign, Henry had graced Bristol with a rare royal visit, and promised to encourage ship building by making investments in the city’s infrastructure. So, developing a trade link between Bristol and whatever was on the other side of the Atlantic was something Henry was willing to consider.

But Henry was practical, and so knew that in the short-term, England’s trade relationship with Spain was more important. The King therefore saw any potential voyage of discovery through the lens of European diplomacy. The Spanish would not be pleased with English interference in their declared sphere of control. In fact, not long after Cabot arrived in England, Spanish agents warned Henry that a charlatan with pretentions of being another Columbus had arrived in his country.

But King Henry was wily enough to see that the threat of an English colonial venture offered leverage in his relationship with Spain. If he could establish an English presence in the New World, that might be a chit he could then trade in exchange for concessions from the Spanish. And he had a very specific concession in mind. In the 1490s, Henry was deep in negotiations to marry his eldest son, Prince Arthur, to Catherine, daughter of the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. (In 1509, Catherine of Aragon, as she became widely known, would, of course, become the first wife of Henry VIII.)

At the time Cabot was seeking Henry’s blessing for his voyage, the marriage talks were at a standstill—though not (as you might think) because Arthur was eight years old and Catherine was nine, but because the Spanish were playing hardball.

Henry had won the throne at Bosworth Field in 1485 by defeating Richard III in battle, bringing to an end the Wars of the Roses. But Henry’s hold on power was still far from secure. In retrospect, we know that England’s long period of civil war was now over, but that was much less clear at the time. Ferdinand and Isabella were not willing to marry their daughter off to a possibly-soon-to-be ex-prince of England.

The source of this uncertainty was a curious historical figure named Perkin Warbeck, a pretender to the throne who claimed to be one of Edward IV’s sons. (The story went that he’d mysteriously disappeared from the Tower of London when Richard III had stolen the throne back in 1483.) We don’t really need to get into the various conspiracy theories surrounding this odd episode in English history, but the important point here is that Spain was holding off on finalizing the marriage treaty until Henry could prove that the Tudor line could hold the English Crown for the foreseeable future.

John Cabot provided the King with an opportunity to apply some pressure on the Spanish, and get them to start taking talks seriously.

With both financing and the backing of the Crown, Cabot headed to Bristol to begin preparations. And by 1496, the project was sufficiently advanced for the King to pay Bristol another royal visit. This was a deliberately showy affair, intended to send a message to Europe. Henry was demonstrating his willingness to annoy Spain, and even hinting at a possible shift in English foreign policy, toward an alliance with Spain’s rival, France. It was carefully engineered theatre, designed to prod the Spanish toward the marriage alliance.

But behind all the bluster, Cabot’s project was running into problems. Although the Italian bankers and the English Crown were on board, the sea-faring community in Bristol required some convincing. The charter Henry had granted allowed Cabot to sail five ships across the Atlantic. But despite energetic arm-twisting, local suppliers had only outfitted a single ship. It’s possible that the fishermen of Bristol were not enthusiastic about their secret fishing grounds becoming common knowledge. Or perhaps there was still bad blood in Bristol as a result of the merchants who’d fallen victim to Italian pirates in the Mediterranean over the previous generation. The idea of an Italian-led and Italian-financed voyage may not have been popular.

Based on the events of the next few years, it seems that one of the few Bristolians who welcomed Cabot was our old friend William Weston. The riches of China were perhaps the one thing that could deliver him from his legal and financial predicaments.

However, the aid of Weston and a few other visionaries (or, desperate men, depending on your perspective) was not enough to sustain a trans-Atlantic voyage. Cabot’s 1496 expedition barely got past Ireland before poor provisions, storms, and a less than enthusiastic crew forced him to turn back to Bristol.

After another year of preparations, Cabot was ready to try again in the summer of 1497. We don’t know for sure, but William Weston probably accompanied him. As one of Cabot’s closest allies in Bristol, and an experienced traveller throughout the Atlantic, Weston would have brought needed skills to the voyage. And the fact that Cabot would later include Weston in the royal privileges the King granted for the exploitation of the newly discovered lands suggests Weston was more than just a passive backer.

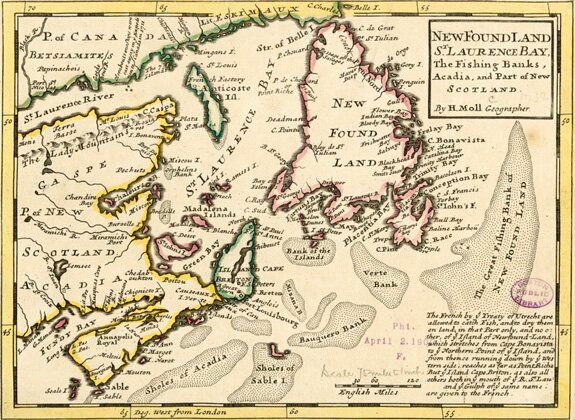

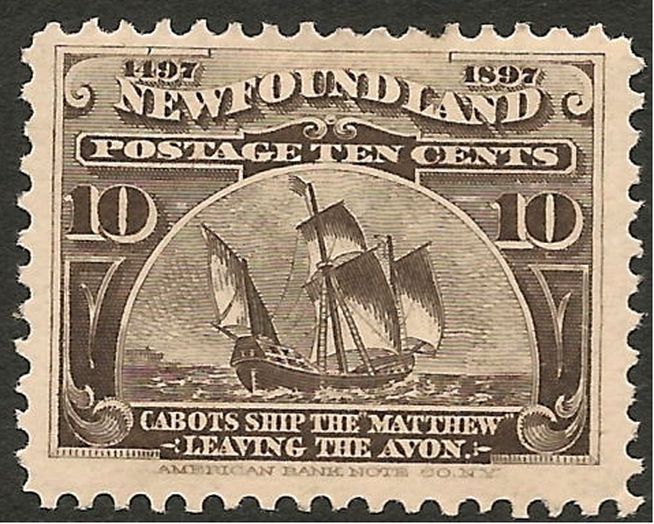

This time, the crossing was uneventful. In June, the sailors sighted land—likely, historians believe, modern day Newfoundland. The Norse had visited the island five centuries previously, and it’s possible that fishermen still had active knowledge of its existence. But for the general English and European audience, this was the first evidence that the land that would become known as Canada existed.

Cabot went ashore in a densely forested area, but did not stray far from the safety of his ship. His tendency toward caution was reinforced when he and his men came across a campsite that had only recently been abandoned. Likely, the camp belonged to the Beothuk, an Algonquin-speaking group then living in Newfoundland. During the winter, they hunted in the interior of the island, but now, in the summer season, they moved to the coast to fish.

Cabot, who commanded a small crew, had no great desire to run into the locals. In this, he exhibited the same tentative attitude as the Norse had exhibited centuries earlier. Outnumbered and far from home, Cabot erred on the side of caution. It would become a pattern among the European explorers who followed him.

Instead of waiting around to meet the residents of the land he’d found, Cabot erected a cross, signifying England’s claim to the territory, then quickly re-boarded his ship. The crew spent the rest of June and all of July exploring the coast, but never again spent any significant time on land. By August, Cabot was back in Bristol, his objective of finding land on the opposite side of the Atlantic complete.

The Italian captain was welcomed with celebrations. King Henry now had his own Columbus to brag about in his correspondence with the other monarchs of Europe. He honoured Cabot as a conquering hero, and awarded him a royal pension. But aside from the fact that Cabot returned as a minor celebrity, we don’t actually know a great deal about the voyage beyond what I’ve already noted.

Some of our best information about the trip actually comes from archives in Italy, rather than England. The agents of the Bardi banking family in London immediately wrote to the head branch in Florence, reporting on the progress of their investment. Their assessment of the value of Cabot’s discoveries, while pretty thin and speculative, is some of the best information we have to go on.

Carbonaro, the monk-financier, also wrote an account of the voyage. As luck would have it, his term as envoy from the Duchy of Milan was coming to an end, and it was common practice among Italian diplomats for outgoing officials to write a kind of school report on the nation they’d served in, in order to help prepare their replacement. Due to his interest in the New World discoveries, Carbonaro included Cabot’s voyages and the potential for future expeditions in his assessment of England.

Part of the reason for the lack of English documentation on the voyage is that Cabot’s return was quickly pushed out of the headlines by much more sensational news. Just a few days after Cabot returned to Bristol, the pretender to the throne, Perkin Warbeck, landed a force in nearby Cornwall. Cabot’s hopes that his discoveries would spur preparations for a follow up voyage were dashed, or at least delayed.

For the next few weeks, Henry and the residents of south-western England were preoccupied with the invasion. By October, Warbeck and an army of Cornishmen had captured Exeter, and were standing outside the walls of Taunton—ominously, just 50 kilometers down the road from Bristol.

Eventually, however, Henry responded with overwhelming force. At the approach of a large, well-trained army, Warbeck lost his nerve and fled his army camp. He was soon captured, and the rebel army surrendered. It was winter before things had settled down enough for Cabot and his friends to lobby for another expedition.

Our old friend William Weston and a group of other Bristol merchants joined Cabot for an official audience with the King to authorize a follow-up expedition in the summer of 1498. This lobbying campaign is the first direct evidence we have of Weston working actively with Cabot (though it is likely their relationship started earlier). The King singled Weston out with a cash prize, which historians treat as further circumstantial evidence that he had been on the earlier voyage with Cabot.

This new voyage promised to be better supported by the Bristol community. Perhaps the confirmation that there were in fact new lands out there drew the interest of the once-skeptical. It also helped that King Henry was pleased enough with Cabot’s discoveries to offer material support this time around: Of the five ships to take part, one would be funded by the Crown. Cabot had no problem filling out the other four vessels.

For the third time in as many summers, John Cabot once again headed west in 1498. Despite this being the largest and best outfitted of the three voyages, we actually know very little about it. Until relatively recently, in fact, it had been assumed that the fleet was lost at sea, since there is no record of its return (though we do have evidence that at least some members of the expedition were alive and well in England a few years later).

It’s in regard to this third voyage, so clouded in mystery, that historian Alwyn Ruddock made her most provocative claims. And in discussing the following, I’ll try to be as clear as possible in differentiating between what Ruddock argued, and what has been confirmed through evidence other historians have subsequently uncovered.

We know that one of the five ships carried a group of clergymen, intent on spreading the gospel to the inhabitants of Cabot’s new found land. Among them was none other than Giovanni Antonio Carbonaro. We also know that early on in the trip, Carbonaro’s ship turned back for repairs in Ireland.

Ruddock believed that Carbonaro’s ship eventually caught up with the other four in Newfoundland. Carbonaro and his colleagues then supposedly established a Church in Conception Bay, on Newfoundland’s south-east coast. Although we have no direct evidence of this (and it’s unclear if Ruddock had any), circumstantial evidence suggests it is a possible scenario. For instance, a later folk tradition held that the European fishermen in the area were tended to by Italian friars. Also, three years later, a Portuguese expedition to Newfoundland discovered Italian-style swords and Venetian silver earrings among the Algonquin-speaking Innu people of Labrador. Strictly speaking, that merely proves contact with Europeans more generally. But a group of Italian friars building the first church in the New World is not an implausible explanation.

Ruddock suggested that Cabot left Carbonaro and his fellow monks in Newfoundland and conducted further explorations down the east coast of America. Cabot may have been at sea for two full years, and could have travelled as far as the Caribbean (where there are reports of the Spanish encountering a European vessel encroaching on their turf during this period).

Whether that was the case, or Cabot and his ships returned home after a more modest interlude of exploring the coast around Newfoundland and Maritime Canada, is not exactly clear.

What we do know is that while everyone waited for Cabot to return, William Weston (who had not gone on this latest voyage) started working on his own expedition, which set out in the summer of 1499 (a year after Cabot’s third departure). As one of Cabot’s initial backers, Weston likely had faith that there were profits to be had across the Atlantic, and it’s likely that Weston had seen Newfoundland with his own eyes during Cabot’s second voyage. But our old friend also had his own, personal reasons for taking up the mantle of explorer.

As his father-in-law had hoped, Weston was unable to afford the upkeep associated with the massive Corn Street mansion he and his wife had inherited. Weston had exhausted just about every delaying tactic he could think of in the courts. The forfeiture of the property was imminent. But the down-on-his-luck merchant had one final trick to play: If he was absent from the kingdom leading a royally sanctioned mission of exploration, then the King would surely offer protections for his property.

Sure enough, when King Henry authorized Weston’s voyage, he also issued a royal injunction, delaying any seizure of Weston’s property until he returned. With any luck, Weston would return a hero, and his legal and financial problems would disappear amid popular acclamation.

It wouldn’t be the last time that an Englishman sought glory in Canada in order to erase his dishonour back home.

If Carbonaro had established a mission in Newfoundland, it’s possible he informed Weston (once he arrived) about where Cabot had gone. Where Cabot had explored the coast south of Newfoundland, Weston turned north. As noted, one of the factors that had originally driven Cabot to work with the English was the fact that any potential passage to the Orient would be shorter the further you got from the equator. With this in mind, Weston may have been willing to brave the colder waters north of Newfoundland.

Hard evidence is sketchy, but it’s possible Weston went as far as the northern tip of Labrador before turning back. He was likely disappointed with how far north the rocky, rugged terrain stretched. As we shall see, he would not be the last Englishman to be frustrated in his quest for a north-west passage.

By 1500, Weston was back in England, and though his efforts were once again recognized with a royal gift, without a passage to the Orient, the monopoly on trade he and Cabot enjoyed would not produce any profits. In the end, Weston’s bid for wealth and fame failed to pan out, and he eventually had to submit to legal and financial realities.

As for Cabot’s fate, we have even less information. If Ruddock is right, he returned from his two-year voyage in 1500 (soon after Weston arrived back in England). The evidence for this is almost entirely circumstantial though. This time, there were no celebrations. This may have been because, after all the initial excitement, multiple trips had confirmed that there was no quick and easy path from these new lands to the lucrative markets of the Orient. It’s also possible that Cabot’s return was swept under the rug because of diplomatic embarrassment. If Cabot did sail into the Caribbean, it would not have been with the blessing of King Henry. Flexing some muscle in the North Atlantic for the benefit of the Spanish was one thing, but infringing on their turf in the tropics was so provocative as to be counter-productive.

Besides, the plan to marry Prince Arthur and Princess Catherine was finally making some progress. In 1499, the young couple was married by proxy, the final step before the treaty could be concluded with the arrival of Catherine in England, and a formal ceremony. Henry may have felt that Cabot’s voyages had served their purpose, having helped bring the Spanish to the negotiating table. A conflict in the Caribbean could only ruin things at this point, and so (the theory goes) Henry quietly pushed the whole business to the side.

A final possible explanation lies with the fate of John Cabot himself. It’s unclear if he died on the voyage, or soon after his return to England. Either way, the driving force behind the expeditions was lost, and so the whole project may have simply faded away.

However, interest in the newly discovered lands in the North Atlantic did not entirely end with Cabot’s death. In fact, his discoveries sparked an interest in the region among the Portuguese.

You’ll recall that the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the globe into the Spanish west and the Portuguese east. But in 1494, neither side knew the contours of the American coastline. As it happened, the eastern tip of Brazil fell on the Portuguese side of the line. And, potentially, Cabot’s newly discovered lands did, too. The only way to be sure was to do some exploring. The Portuguese were motivated to do this before the English embedded themselves in the region.

King Manuel I commissioned Gaspar Corte-Real, the son of one of Portugal’s great explorers, to defend the kingdom’s interests in the North Atlantic. In 1500 Corte-Real (re)discovered Greenland—about 50 years after the last Norse settlement had been abandoned. He returned in a follow up voyage the next year, then pressed on to the west, exploring the Labrador coast down to Newfoundland. (These were the Portuguese I mentioned earlier, who discovered possible evidence of Carbonaro’s mission.)

Unlike Cabot, Corte-Real met the Beothuk people who populated the island. But it was not a pleasant encounter. Corte-Real seized more than 50 locals, and shipped them back to Portugal in slavery. The experience was a formative one for the Beothuk, who learned to hate and fear Europeans. As more and more Europeans arrived in the area (mostly to fish), the Beothuk retreated further inland, altering their usual seasonal migrations to the coast for summer fishing. This set them apart from the other peoples native to the east coast, who (in the coming decades) would welcome European fishermen as trading partners.

Corte-Real diverted two of his ships to bring his human cargo back to Portugal, but he himself decided to continue charting the coast to the south. It’s unclear how far he got. No one saw him or his ship ever again. Corte-Real’s brother, Miguel, set out to find him the following year, but he too was lost at sea.

Henry and the English would continue to have an interest in Cabot’s new found lands, too. As long as the voyages were limited to the North Atlantic, friction with the Spanish was more diplomatically useful than provocative.

The King was aided in this by the highly competitive job market for Portuguese explorers. Portugal’s overseas trade and navigation schools produced more pilots and explorers than could be employed by Crown-authorized commissions. Portuguese graduates who failed to win government contracts looked to England for work.

In 1501, King Henry commissioned Joao Fernandes, an explorer based in the Azores, to make an English claim on the newly re-discovered Greenland. Fernandes had been on Corte-Real’s voyage in 1500, but on his return, had failed to secure a Portuguese commission to conduct exploring of his own. His first voyage to Greenland was successful. But, following in the tradition of Corte-Real, Fernandes was lost at sea the following year.

While all this was going on in the North Atlantic, a diplomatic crisis suddenly erupted. In November 1501 (in between Fernandes’s two Greenland voyages), the Spanish princess finally arrived in England, and Arthur and Catherine were married. Henry’s Tudor dynasty was secured, and the alliance with Spain formalized. Then, just months later, in April 1502, disaster struck: Arthur, the heir to the throne and still just 15 years old, died of an illness.

There was a way to salvage the situation, however. Henry had a younger son, the future Henry VIII, who could potentially step into his brother’s shoes. The alliance need not be lost.

This, however, would require more rounds of negotiations, as the Bible had a clear injunction against a man marrying the widow of his brother. Both England and Spain would have to appeal to the Pope for a special dispensation allowing the marriage to go forward.

Also, Prince Henry was just 10 years old when Arthur died, meaning a formal wedding would have to be delayed anyway.

Eventually, this second marriage would go forward. In fact, it would end up being perhaps the most consequential marriage in English history, setting the stage for Henry VIII’s English Reformation.

What’s important for us here is that while the negotiations remained in progress, English voyages into the North Atlantic retained their diplomatic importance (in addition to their overt commercial goals).

After the death of Fernandes in 1502, Henry adapted the commission he had given to the Portuguese explorer into a company, based in Bristol, with a charter to seek further opportunities in the newly discovered lands. Several voyages followed, culminating in 1508, when John Cabot’s 34-year-old son, Sebastian Cabot, led an expedition in search of the north-west passage that William Weston had failed to find. Again, we don’t know precisely how far Cabot got, but it’s possible he penetrated into the Hudson Strait, between Baffin Island and northern Quebec.

However, if Sebastian Cabot hoped for a follow up voyage to push further west, he was to be disappointed. When he arrived back in England in 1509, he was greeted with momentous news. King Henry VII had died. His son now reigned as Henry VIII, alongside his new Spanish wife, Queen Catherine. The diplomatic incentive for the Atlantic voyages disappeared, and the new Henry was not as interested in commercial opportunities as his father had been. For Henry VIII, true power lay in European geo-politics, not catching fish on the other side of the world. Royal support for voyages of exploration dwindled, and a frustrated Sebastian Cabot left England for Spain, in search of a new royal patron.

English fishermen (primarily based out of Bristol) continued to travel to Newfoundland every summer. But state-backed attempts to find a passage to the Orient, or any other commercial opportunities in the New World, would be off the table for the next few decades. It would take another set of shifts in Atlantic commerce, and European diplomacy (as well as a few changes in leadership at the top of the Tudor monarchy) for English interest in Canada to pick up again.

In the immediate term, further exploration would fall to other powers. Following years of European fishermen plying the shores around Newfoundland, knowledge of the area was improving. Some began to suspect that Cabot and Weston had been mistaken: The passage to the Orient was not north or south of Newfoundland, but to the west.

Beyond the island lay a wide channel that appeared to run deep into the continent. Soon, a new group of Europeans, the French, would seek the riches that lay up what came to be known as the St. Lawrence River.