Canada

An Immigrant’s Ode to Canada

A survivor of Sri Lanka’s civil war who found safety and wealth on Canadian shores wonders why his well-to-do white neighbours seem so fixated on racism.

In June 2017, I was asked to give a Walrus Talk at the Vancouver Art Gallery about my experience in Canada. There were a few other speakers as well. In my speech, I briefly mentioned the very first Canadian I ever met: the visa officer at the High Commission of Canada in then-war-torn Sri Lanka, Robert Orr. After my talk, one of the other speakers told me that he knew Bob from his days in the diplomatic corps, and provided me with Bob’s contact information. I was thrilled, and sent Bob an email right away. A few days later, he replied. We set up a lunch meeting in Ottawa.

Three decades later, it was nice to again meet, and thank, the man who had granted me entry to Canada. I was a little surprised when he thanked me as well.

“You have no idea how much it meant to hear from you and to know that things worked out so well,” he said. “As a visa officer, you would see the ‘before’ picture, but rarely do you know what happened after to people you had the opportunity to accept.”

The thing is, as much as I admire and respect Bob, my friendship with him is not unique. I have been a Canadian for a long time now, and I have met countless Canadians who have treated me with the same open-heartedness. I remember once walking through the lunchtime chatter of the business crowd at Calgary’s Petroleum Club during the Stampede when I heard a booming voice from several tables away.

“There goes my favourite brown guy!”

The room got a lot quieter. I peered through the crowd to identify the speaker. Then I saw this barrel-chested man in a 10-gallon hat and cowboy getup.

He walked up to me and gave me a big bear hug, “I love you, brown guy.”

“I love you, too, honky,” I replied loudly.

We both broke out into laughter. The business crowd went back to their chatter and negotiations once they’d witnessed two old friends’ tomfoolery.

It was one of my financial firm’s big clients and, more importantly, an amazing friend, Brian Hein. One of the nicest people I have met in my life. So kindhearted and generous in spirit. Our relationship was almost two decades old. It was people like him who had given me a chance when I was a young and inexperienced salesperson travelling through western Canada.

I have met many people like Hein across Western Canada, from Winnipeg to Victoria. I have slept in their homes. I know their spouses and kids. I’ve gone on hunting and fishing trips with them. I’ve had clients bring me fresh moose meat to business appointments. I’ve attended the Calgary Stampede with them. (Never missed one in 20 years, until the pandemic shut things down in 2020.)

I suspect I got to know Canada in a way few immigrants have: by travelling through small towns, giving sales speeches to rooms full of farmers and coop managers in Dawson Creek, Prince George, Smithers, Fort Nelson, Brooks, and Lethbridge. Often, I would be the only non-white person in the room. One time, when it was my turn to address the audience, I said, “Geez, it’s a good thing I’m here, otherwise this might look like a Klan convention.” The room erupted in thunderous laughter. They got it.

Other times, to break the ice, I’d make jokes to help defuse the social anxiety in a room. Like if a guy was named James, and I called him Jim, I’d say, “Oh, you white guys and your complicated names.” They got that, too.

How many times have I heard, “Oh, that’s an interesting last name! Where is it from? Is it short for something? Tamil, eh? Where are you originally from?” Like many Tamils, I have been asked that a lot.

Does asking a question like this make you a racist? I imagine that depends on how you define racism. But do such questions bother me? Why should they? I am proud to be Tamil. Why would being asked about it bother me?

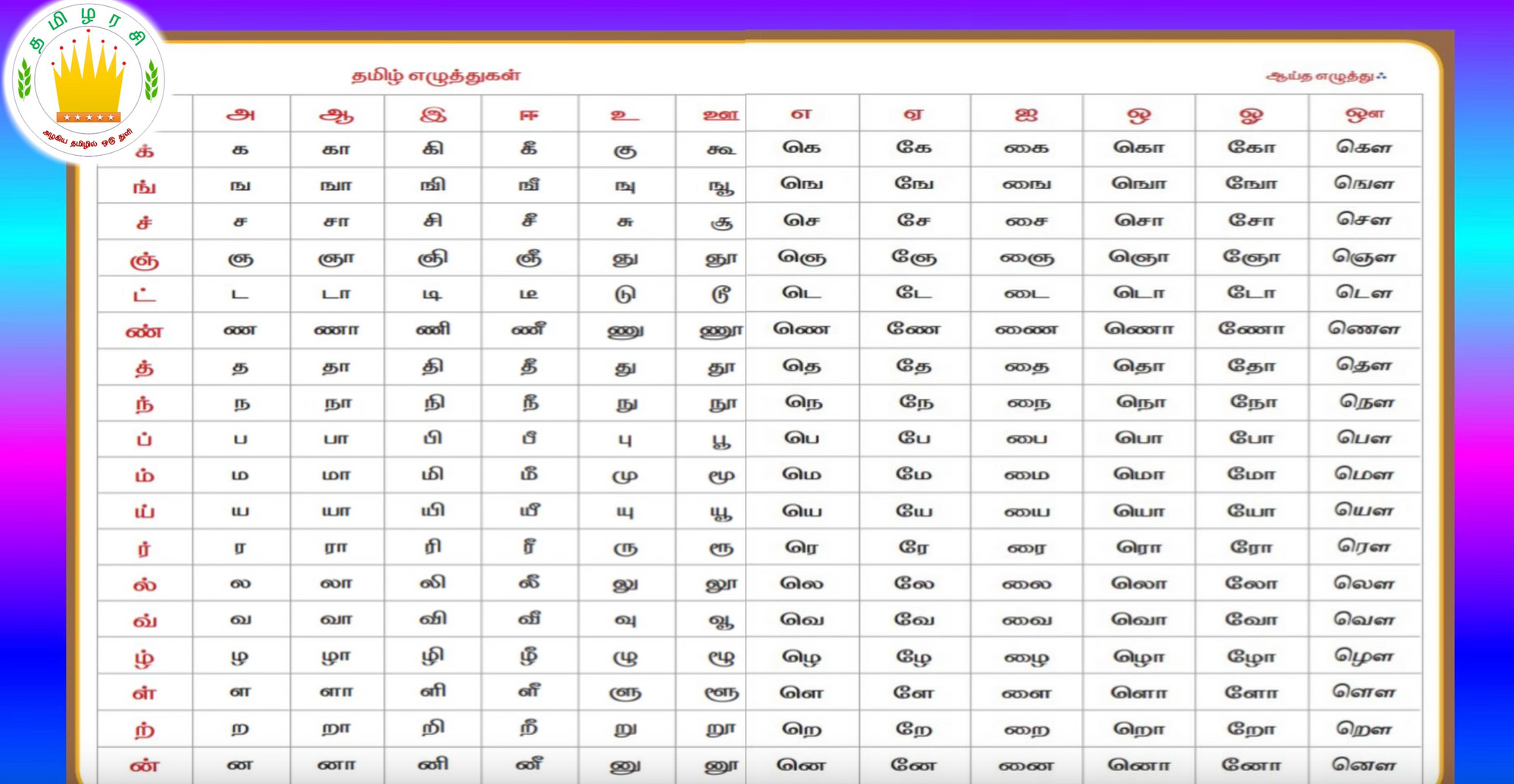

As for my name, well, the length of Tamil names is an objective fact. They’re long. Tamil names, when translated to English, take on a vast array of letters. Mostly vowels. It can look like an optometrist’s eye chart. The Tamil language has 247 characters. We have to find a way to use them all. My last name has eight letters. That’s a short name by Tamil standards. My mother’s maiden name has 16. You can’t fit that on a hockey jersey. Should I be embarrassed that the alphabet of my native language has more letters than English does? For the life of me, I can’t see why. No one has ever explained to me what I have to be embarrassed about.

Of course, I do realize that such questions are considered impolite in some circles. Every culture has its own manners, and I respect that. If asking where someone is from is like using the wrong fork at dinner, I get it. It’s frowned upon, and it separates the self-consciously polite people from those who may pay less attention to subtle rules. That’s fine. But before we dismiss the people who ask those questions as boors or something worse, I need to be clear. I have done a lot of fundraising events with my clients and friends. Some of them might have been politically incorrect, but they were the first to donate to charities. And when the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 laid waste to Sri Lanka, many of my Western Canadian friends called to see if my family was okay. They wanted to donate whatever they could.

I am proud and honoured to have been able to learn about Canada the way I have. I feel as though I have had the opportunity to see the real Canada. The generosity and warmth of the Canadians I have met match up with the humanity of the first Canadian I met. Canadians have treated me the way I would treat them.

Of course, if you grow up in Canada, you may never notice how exceptional it is. You may not notice that in many other places—perhaps most—ancient hatreds still shape everyday life. It is not everywhere that you can walk into a room of people who look different from you and expect to be greeted warmly. What we have here is special. And I want to make sure my son never takes it for granted.

Still, I was surprised one lazy Saturday morning by a jarring question from my then-six-year-old son. “Were you sad when you were in prison, Daddy?”

The morning’s tranquility was shattered. Honesty isn’t easy in a moment like that. Not when it invites the ugliness of the dark past to the sunny breakfast table. Once he had asked me what happened to his appāppā (grandfather), and I lied, saying he had died in an accident to spare the kid from my nightmares. In fact, he had been killed in Sri Lanka on April 21st, 1988, just three days after he put me on a plane to Canada.

I was shocked by the question. I had never told him that I had been in prison when I was a teenager in Sri Lanka. He must have overheard conversations between my wife and me. But this was no time to lie.

“Yes,” I said.

“Are you happy now?”

“Yes, very happy.”

“Why, Daddy?”

“Well, because I feel safe to live with my family in Canada—that’s why. In this country, people of minority groups do not wind up dead.”

That was probably the wrong answer to give a six-year-old. At that age, injustice is something that happens on the sandbox scale, and death is something distant and abstract. Aaron probably had no idea what I was talking about. He just went on doing his own thing.

But I thought about it a lot. And I see now that the reason Canada is safe is that Canadians treat others the way they want to be treated, just like Bob Orr.

Canada has taught me some important lessons. I didn’t arrive here fully formed or brimming with wisdom. Like all young people, I thought I knew more than I actually did. One important lesson was offered to me at an investors’ meeting in Lethbridge, Alberta.

If you’re like most Canadian urban-dwellers, you’ve probably been told that Lethbridge is a town full of rednecks. That’s what I thought, too. When I walked into the hall where all the investors were sitting down to dinner, the only spot I could find was with an older, blue-collar couple. I assumed I was in for a dreary evening trying to make conversation with these bumpkins.

I discovered how wrong I was as soon as I sat down and made an observation about the wine. As it turned out, the husband knew more about wine than I did. When I mentioned that I was from Sri Lanka, the husband spoke knowledgeably about the northern part of the country; it turned out that he had spent months there, volunteering in the effort to rebuild in the wake of the 2004 tsunami.

Despite whatever I thought I could tell about this couple from their appearance, they were well read, widely travelled, and generous, decent, warmhearted human beings. We remain friends to this day. When I got back to my room that night after hours of great conversation, I was humbled and ashamed. What had led me to think I had been entitled to judge them? That in itself bespoke a blinding vanity. And I was blind. I thought I knew who they were at a glance, and I was completely wrong.

I have never forgotten that lesson. You can’t tell what a person thinks from what they look like. Few people would disagree. We all learn that in school. But many of us act as though you can tell. Some people think I’m oppressed just because I’m not white. Some people think a white person who is not wearing fashionable clothes is a bigot.

As a youngster, I had seen Sri Lanka fall to pieces in a war rooted in a very real and deadly form of bigotry. I know what real hatred looks like. It is human nature to prejudge people in a group based on what we’ve heard or our past experiences. There is no changing that. It is what comes next that we control. We take those prejudices and compare them to the individual. If our eyes are truly open, we are often humbled.

A bigot is a person who doesn’t change their mind regardless of the character of the person they meet—no matter what colour their own skin may be. Trust me, there are plenty of brown bigots. The overwhelming majority of white people I’ve met are not. Like other characteristics, bigotry has nothing to do with skin colour.

Just to be clear—this is a source of great optimism to me. This is why a certain Colonel Dudley Fernando saved my life after I was arrested, tortured, and thrown into a Sri Lankan prison three-and-a-half decades ago, even though he was Sinhalese and I was Tamil, just like the Tamil Tigers the government was then at war against. He didn’t see me as an ethnic enemy. He knew my father, and saw me as a friend’s son.

That’s humanity. And this is why I have many Sinhalese friends. Their ethnicity does not implicate them in the policies of a government that killed many innocent Tamils. I treat them the way I would want to be treated. They do the same for me.

It is amazing what you can learn over dinner. When I go to small towns, I meet people who don’t even think about race. When I have dinner with well to do urbanites, I sometimes get the impression that race is all they think about. Nice white ladies often go out of their way to sympathize with me about all of the barricades that racism has thrown up to thwart my success here in Canada.

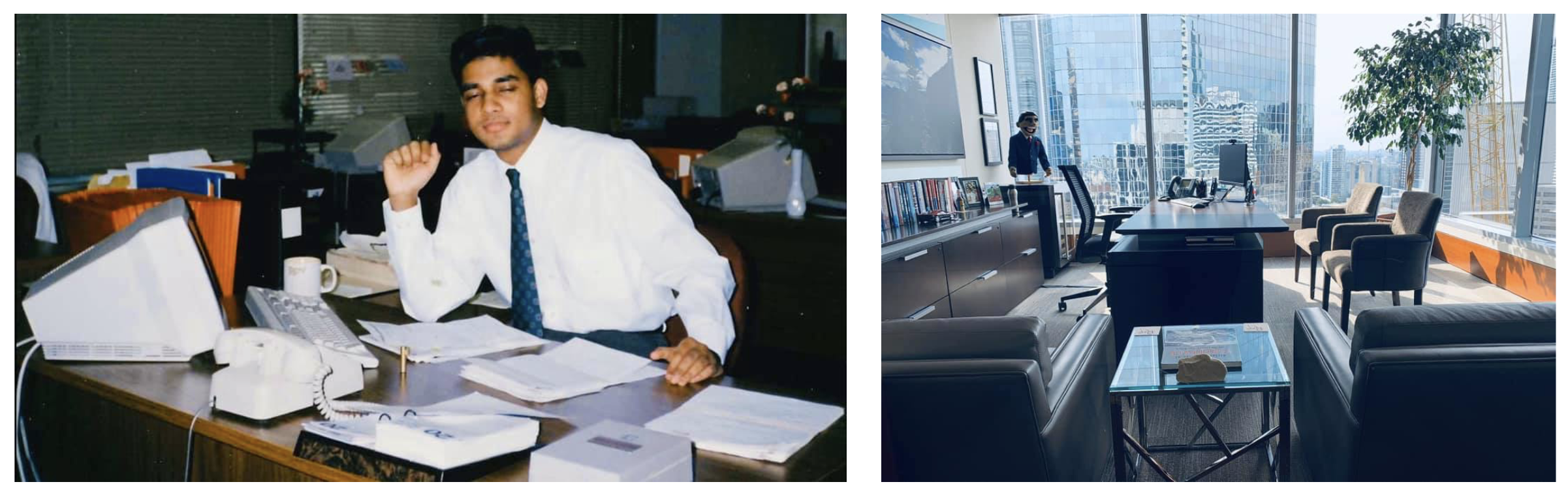

Oddly, I don’t see things that way. I think I’ve done all right. I was named one of Canada’s 50 best executives in 2020 by Report on Business. The award was for individuals leading their companies through COVID and helping build a better country in the process.

I’m not saying I deserved all that. When Report on Business contacted me about it, I thought they had the wrong guy. My point here is not that I’ve done a great job. My point is that white Canada has not held me back. It’s that Canadians have helped me every step of the way.

I have to admit that this testimony almost never changes people’s minds. One particular well to do progressive made the argument that if I hadn’t been oppressed by white privilege, I must therefore have benefited from it. In her view, I am now part of the denigrated, despised “one percent.” Since I live in a nicer part of Toronto and have moved up a few rungs on the economic ladder, in her view, I’m now incapable of understanding or sympathizing with the plight of people of colour, despite my past. “You have sold out to the system,” she claimed.

She may have meant that as a compliment—since now I, too, would be entitled to make a spectacle of hating myself. But what boggled my mind was her assumption that by becoming successful, I had also become white. This sentiment is also common among some brown folks. According to them, I’m a coconut: white on the inside, brown on the outside.

Recently, someone took offence when I said that I believe in lowering the barrier, not the bar. I believe in meritocracy, and I only hire talent, regardless of race, religion, or sexual orientation. To my amazement, a white person replied, “You don’t understand the struggles of people of colour.” It was a virtual meeting, so I thought I must have had my camera off. But no. It was on. This white woman was looking at my “coconut” brown face and assuming that she knew better than I did what life is like for someone like me.

That logic is simple: if you happen to be a person of colour, you are by definition oppressed. If you are not oppressed, you are not a person of colour.

This kind of attitude feels a lot like condescension. The immigrants and people of colour I know want no part of it. In fact, most of us don’t want to be seen as members of a group at all, let alone members of a group to be pitied.

It took me over 30 years to get here. As a South Asian migrant who came to Canada as an impoverished teenager, and rose from a mail-room job to assume a leadership role on Bay Street, I don’t believe that there is a shadowy white man out there trying to keep me or people of colour down in life. Like many newcomers, I achieved success through hard work and determination. Now so-called progressives want to discredit that and take it away from me? No thanks.

I had to create my own life. I had to go from “Subēndraṉ” to “Roy.” I had to learn how to properly enunciate words in English, and I had to learn to crack jokes and endear myself to Canadian sales audiences. I had to outwork everyone and everything. I never wanted to be a victim. So don’t call me that.

Excerpted in abbreviated form from the #1 best-selling Canadian book Prisoner #1056: How I Survived War and Found Peace by Roy Ratnavel. Copyright © 2023 Roy Ratnavel. Published by Viking Canada, an imprint of Penguin Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.