Sixty years ago this summer, American International Pictures released the first entry in a cinematic genre that would come to be known as the beach party film. Appropriately titled Beach Party, it starred (among others) Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello. It was a surprise hit, bringing in $2.3 million at the box office, which was nearly 10 times its production budget. Over the next five years or so, AIP released another 11 similarly-themed films—Muscle Beach Party, Bikini Party, Pajama Party, and so on—most of which also featured Avalon and Funicello. Although only the AIP entries are generally considered canonical, Wikipedia contends that the genre comprises over 30 films, including movies from other studios.

Wikipedia also notes that the genre owes a great deal to a fictional 15-year-old girl named Franziska “Franzie” Hofer. She was the creation of an Austrian-American novelist and screenwriter named Frederick Kohner, a Jew who fled Nazi Germany for Los Angeles in 1936. He based Franzie on his younger daughter Kathy, who was born in Los Angeles in 1941. In 1956, she began spending her days on the beach at Malibu, where she became an avid surfer and hung out with a gang of male surfers, all of whom were several years older than she was. Kathy was only five feet tall, so the surfers, who nicknamed practically everyone in their circle, nicknamed her Gidget (a portmanteau of “girl” and “midget”).

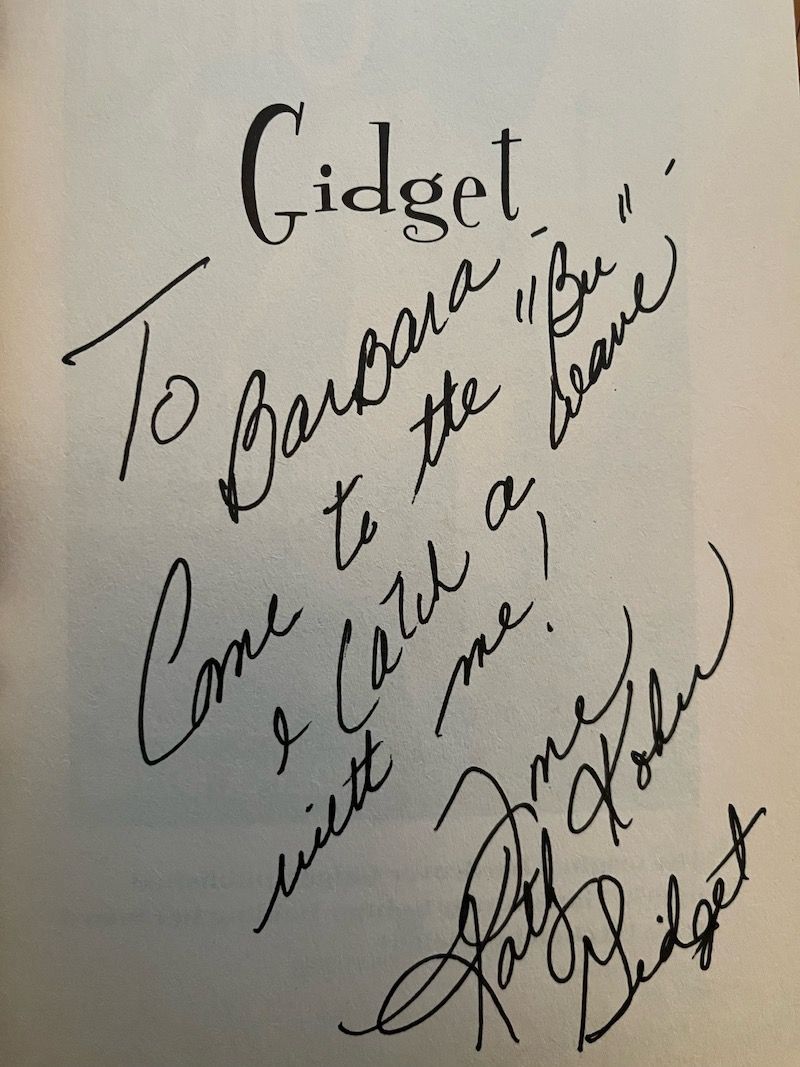

In the summer of 1956, Kathy’s father drove her from Brentwood to Malibu every day, where she would spend hours surfing with her new friends. In the evenings, he would pick her up and drive her home. During those evening drives, Kathy dazzled her father with the surfing slang she had learned from her older companions. She kept a diary and wanted to write a book about her experiences, but she wasn’t a professional writer. So, her father encouraged her to tell him all her stories with the promise that he would write the book himself. Every evening for about three weeks, Kathy described her adventures to her father. He spent another six weeks writing them up in fictional form and then sent them off to a literary agent.

Kathy never read the manuscript but, a few weeks later, her father got a call from a representative at the William Morris Agency. According to Kathy, the agent told Frederick, “[T]his is going to be a play, this is going to be a TV show, this is going to be a comic strip, this is amazing. You’ve hit the jackpot, Mr. Kohner.” The William Morris agent proved to be prophetic. The book—originally titled Gidget, The Little Girl with Big Ideas—was published in October 1957, by G.P. Putnam’s Sons, and became a cultural phenomenon. A second hardback edition was produced just one month later. A 1986 Los Angeles Times article about the Gidget phenomenon noted that, when Kohner’s book came out, “Reviewers were so startled by the life style that some of them couldn’t be sure whether he was kidding, had wigged out or was making it all up.”

In California Golden, a novel about female surfers of the 1950s and ’60s scheduled to be published this August by Delacorte Press, author Melanie Benjamin describes the Gidget phenomenon through the eyes of two young sisters, Mindy and Ginger Donnelly, whose mother is a competitive surfer:

In 1957, an earthquake shook California. It wasn’t the San Andreas fault; it was a girl not much older than Mindy. A girl named Gidget. The book—Gidget, the Little Girl with Big Ideas—was all anyone could talk about. The girl on the cover, with her dark ponytail and surfboard, smiled at Ginger wherever she went—the library, the Rex-all, the big Broadway department store in the new Panorama Mall. Suddenly everyone—not only weirdos like Mom—wanted to surf. … [S]urfing became cool, all of a sudden. And the kids at school peppered Ginger with questions about her mother—“Does she know Gidget?” “Is Moondoggie really that cute?” “Does she say bitchin? I can’t imagine my mom ever saying a curse word!”

By the time its first paperback appeared in August 1958, the novel had shed its ungainly subtitle and was now simply known as Gidget. Over the next decade or so, the book spawned five official sequels and two novelizations (written by Kohner but based on screenplays written by Ruth Brooks Flippen). The books were translated into a dozen languages and sold more than 30 million copies.

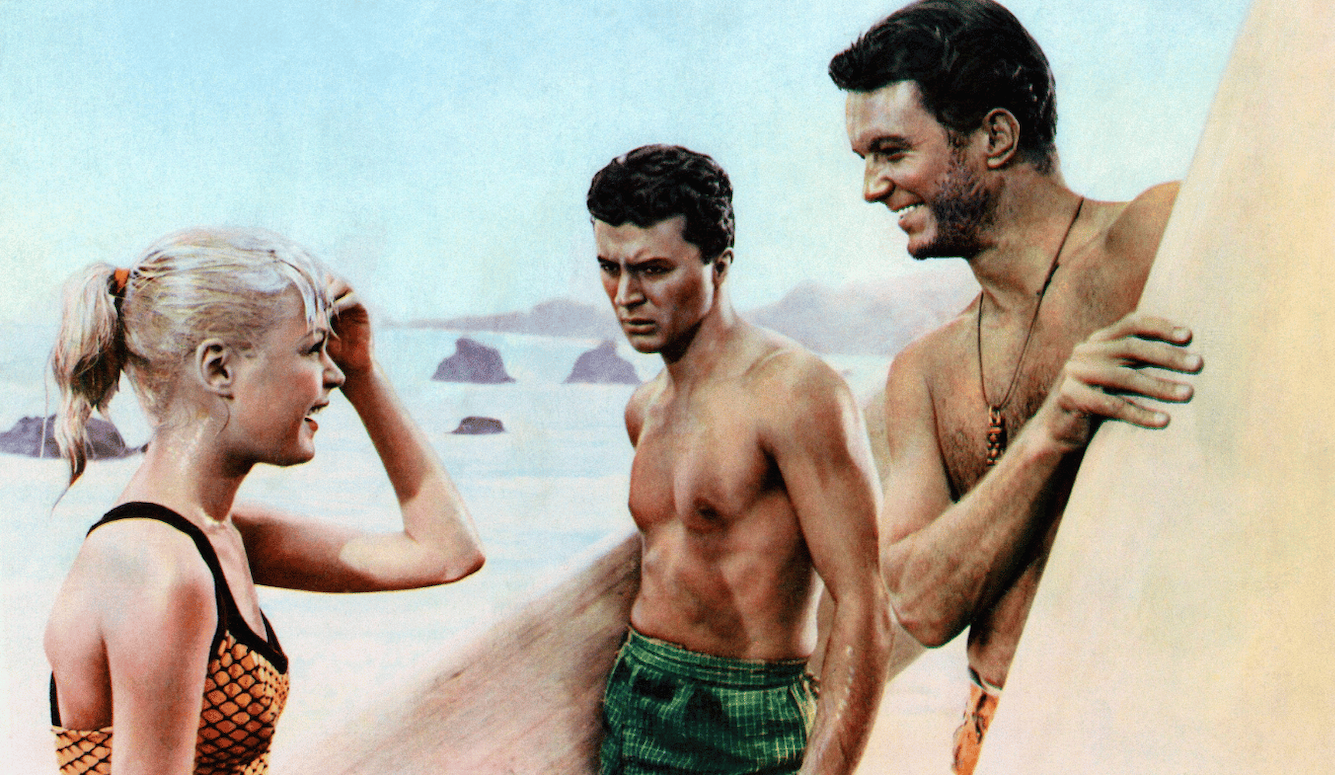

In 1959, the original novel was made into a film starring Sandra Dee as Gidget and James Darren as her love interest, Jeff “Moondoggie” Matthews (the studio wanted Elvis Presley for the role but the US military had other plans for him). The film generated two official sequels, 1961’s Gidget Goes Hawaiian (starring Deborah Walley in the title role) and 1963’s Gidget Goes to Rome (starring Cindy Carol). Darren co-starred in all three films and, according to the LA Times, “holds a special place in film history. He is the only actor to appear in a movie franchise opposite different leads in each outing: one Moondoggie, three Gidgets.”

Of course, Gidget also spawned a lot of unofficial sequels, including all those beach party films in which Annette Funicello, who stood five feet and one inch tall in her bare feet, played a variation on the same diminutive character. It also spawned a short-lived but influential TV series starring Sally Field that debuted in September of 1965, a 1969 made-for-TV film, Gidget Grows Up, which starred Karen Valentine, and a 1972 TV film called Gidget Gets Married, which starred Monie Ellis. The franchise was rebooted in the 1980s with a TV film, Gidget’s Summer Reunion (1985), and a syndicated TV series called The New Gidget, which ran from 1986 to 1988 for a total of 44 episodes. Both Gidget’s Summer Reunion and The New Gidget starred Caryn Richman. After Monie Ellis (who is too obscure even to merit a Wikipedia entry), Richman was perhaps the least famous actress to tackle the role of Gidget, but she spent more time in it than anyone else.

In the first Gidget novel, the character is given no last name. In subsequent novels, she is Franzie Hofer. In her various Hollywood incarnations, she is Frances Lawrence. Wikipedia notes that the change was made to give her a name that was “more English-sounding,” which is a polite way of saying, “less Jewish-sounding.”

Numerous authoritative sources cite the Gidget books and films as the intellectual properties that did the most to bring surf culture into the American mainstream. Surfer magazine ranked Kathy Kohner number seven on a list of the 25 most influential people in surfing history (she has also been inducted into the Southern California Jewish Sports Hall of Fame). Through the years, thanks largely to Hollywood, Gidget has come to be seen as an avatar of the squeaky-clean American girl of the 1950s and early ’60s, before hippie culture came along and complicated the lives of American teens. Though she was a staple of the pop culture on which American Baby Boomers were raised, neither Gidget nor her real-life inspiration were actual Boomers. Kathy Kohner—who has been married to Marvin Zuckerman since 1965 and is now known as Kathy Kohner-Zuckerman—is one year older than President Joe Biden and was born into the so-called Silent Generation of Americans.

By the 1970s, the Vietnam War, the campus protests, the hippie movement, the assassinations of several major political and cultural figures, and other shocks had begun to make the world of Gidget seem like some long lost Eden. Films such as American Graffiti, Broadway plays such as Grease (which contains a song called “Look at Me, I’m Sandra Dee”), and TV shows such as Happy Days and Laverne and Shirley cast a roseate glow on an era that was only about a decade and a half in the past. But Gidget isn’t quite as innocent as you might have been led to believe.

The paperback was published the same month as the first American edition of Lolita. The books bear at least a few similarities to each other. Both Lolita and Gidget were published in hardback by G.P. Putnam’s Sons. The titles of both books are nicknames given to underage girls by an older man (Gidget is also variously referred to as Undine, Gnomie, Pinky, Shorty, Kiddo, and a lot of other handles). As noted, Gidget is 15 during the summer described in the novel. But she hangs out with, and is lusted after by, several men who are well into adulthood. She drinks beer, smokes cigarettes, and visits bars. At one point she spends a night in bed with the oldest of the surfers, nicknamed the great Kahoona, although, to her disappointment, they don’t have sex. The book is filled with language that flirts with obscenity. The male surfers, for instance, refer to Gidget (and various other young women) as a “coozy” (which would seem to be related to the word “cooze”—it’s not clear if Kohner, for whom English was a second language, was aware of the latter’s sexual connotations).

The surfers Gidget hangs out with—guys with nicknames like Scooterboy Miller, Hot Shot Harrison, Golden Boy Charlie, Lord Gallo, and Malibu Mac—are clearly interested in Gidget sexually. They frequently direct surfing-related double entendres towards her: “Want to go tandem?” “How about waxing my board?” “Let’s drag the Gidget in the hut and teach her some technique.” Kahoona warns Gidget that these guys are interested in teaching her more than just how to surf. She feigns indifference, telling him, “I’ve been around. I can take care of myself.” But Kahoona (whose real name is Cassius, though it’s usually shortened to Cass) persists: “I’m leveling with you Franzie. Those guys out there—they’re a bunch of roughnecks. Some go to college and all that—but they’re bums at heart.” He takes a sort of protective attitude towards Gidget, but the other surfers believe he just wants her for himself. One of them chides him by dubbing him “Ole Cradlesnatcher.”

Once Gidget becomes a member of the surf gang (known as the “Go-Heads of Malibu”), she seems to become a bit of a communal make-out partner. She tells the reader, “They were regular guys—none of those fumbling high school jerks who tackle a girl like a football dummy. No sweaty hands and struggles on slippery leather seats of hot rods. The bums of Malibu knew how to talk to a girl, how to handle her, how to make her feel grown up.” This is all very weird when you consider that Kohner was essentially writing about his own 15-year-old daughter (the book is dedicated: “To the Gidget—with love.”). It’s tempting to believe that Kohner’s frequent double entendres are actually unintentional, the result of the fact that he wasn’t writing in his mother tongue. But Kohner was a worldly European and apparently much more sanguine than the average American about underage girls being viewed as sex objects. In 1967, he would publish Kiki of Montparnasse, a memoir of his friendship with Alice Prin, a famous French model and muse who began posing nude at the age of 14—so young, in fact, that she had to draw pubic hair on her body with charcoal in order to appear older. I don’t think that Kohner was trying to write a softcore version of Lolita, which had been published in Europe a few years earlier. But it seems almost certain that Gidget was intended to be a sort of stealth version of Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse.

While Lolita’s Humbert Humbert is definitely a pedophile, the surfers in Gidget are not. Gidget may be legally a minor, but she is not prepubescent. At one point, she notes that, “ever since I got back from Europe I had become especially desperate to grow up. … Not biologically … that’s long behind me.” In fact, while she was in Europe, at the age of 14, Gidget had fallen in love with a US serviceman in Germany, an American student in Switzerland, and a travel agent in Italy. Her hormones appear to have been raging long before she fell in with the Go-Heads. (Incidentally, Lolita’s real name is Dolores, which is also the name of Annette Funicello’s character in Beach Party, a character who, like Lolita, inspires the intense interest of a much older professor.)

In Kohner’s book, Gidget and the surfers frequently use the adjective “bitchen.” I can’t determine whether this is how Kohner thought the word was actually spelled or if the publisher changed the spelling in order to make it less offensive than the more correct “bitchin’.” It was probably just a misspelling on his part. The book contains several others. The great Kahoona takes his name from a Hawaiian word meaning “artist” or “trained professional” (some insist that it merely means “chief”), but the word first appeared in a Hawaiian-English dictionary back in 1865, and is properly spelled “kahuna.” A “great kahuna,” in surfer slang, is just a master surfer. Naturally, some people nowadays consider the use of the word in reference to a non-Hawaiian to be cultural appropriation and offensive. In 2004, when Dodge was planning to produce an SUV called Kahuna, some native Hawaiians protested the decision and the plan was dropped. When the 1959 film came out, Kohner’s spelling error was corrected and Cliff Robertson’s character was called Kahuna.

Among the words that appear in the novel are “goddamn,” “hell,” “Jesus H. Christ,” “crap,” “knockers,” “boobs,” “jugs” (the surfers are all ardent fans of Playboy magazine, despite the fact that, in the summer of 1956, it had been in existence for only two and a half years), “turd,” “bastards,” “sons-of- bitches,” “Chrisamighty” (sic), and “faggot.” At one point, Gidget tries to get invited to an orgy. When all her efforts fail, she writes, “I got blewed, stewed, and tattooed, but that’s how far I got. I remained the uninvited.” The only off-color word in the book that made it into the film intact was “orgy.” It appears numerous times in the book but only once in the film.

Occasionally, Kohner disguises a term that might’ve been censored otherwise. In one scene, where a contemporary writer might use the term “tough shit,” Kohner (as Gidget) writes “T.S.” and leaves it to the reader to work out what the initials stand for. In case of any doubt, a few pages later, when a fire breaks out on the beach, the crowd of surfers begin to let fly with various expletives: “Jesus Christ!” “Dammit.” “Chrisamighty.” “Tough sh--.” Kohner’s idiosyncratic use of English can sometimes be confusing. When the fire prevents Gidget from going home, Kahoona offers to let her spend the night in his beach hut. But she has reservations:

I had never slept with a man in one room. Not to speak of a hut. I got frightened, naturally. Let’s say I’d fall asleep. He might rape me. It had happened before.

That makes it sound as if Gidget has previously been raped, but most likely she means, “That kind of thing has happened to plenty of other girls.” In any case, her fear of rape evaporates quickly when Kahoona lies down next to her in bed:

It was shocking and overwhelming, feeling a man’s body like that. At this moment I knew that I had never lived at all. Maybe I had not even been born yet. All my fears and frustrations seemed to melt away in a sudden blaze. Yes, this was the moment I had been waiting for. Now it would happen. He would make me a woman. And then I could have any man I wanted to. I could have Jeff.

The novel includes a scene in which Gidget grows uncomfortable as the surfers discuss the voluptuous bodies of various actresses—Gina Lollobrigida, Sofia (sic) Loren, Anita Ekberg, Jayne Mansfield, and so on. One surfer notes that Ekberg’s breasts “need a hammock for two.” Another makes a play on Jayne Mansfield’s last name: “I’d fertilize that Mansfield any day!” One of the surfers asks Gidget if she is a good girl or a nice girl. She responds, “What’s the difference?” And he explains: “A good girl goes on a date, goes home, goes to bed. A nice girl goes on a date, goes to bed, goes home.” “So – what kind of a girl are you, Gidget?” Malibu Mac asked with a leer.

Gidget was being sexualized by the men around her before she was really ready. What makes this so painfully ironic is that the two best-known portrayers of Gidget—Sandra Dee and Sally Field—were both abused by their stepfathers as young girls. In fact, the abuse of both girls took place in the 1950s, the era that the Gidget film idealizes as a halcyon era for the American family. At times, Field’s excellent 2018 memoir, In Pieces, reads as Lolita might have read had it been narrated by Dolores Haze rather than her abuser.

“Open your mouth,” he breathes.

I don’t.

He sets his penis, as muscular as the rest of him, between my legs and pulls my littleness towards him … and it.

Field was 12 years old during that incident with her stepfather, actor and stuntman Jock Mahoney—the same age as Dolores Haze when Humbert Humbert first came into her life. The Gidget TV series turned out to be a great experience for Field, practically a lifesaver, since it got her out of a nightmarish situation at home. In her memoir, she writes:

Approximately eight weeks and a handful of surfing lessons later, production began and I walked through the looking glass. On one side was my life, my real life as it existed, and on the other side was a greatly altered world. And my God, how I loved the girl on that side of the glass, loved her ease around people, her trust in them. She was pure and untarnished. My twin sister, who looked very much like me, was a part of me, and yet was not me. For thirty-two episodes—and many more weeks than that—her house, her friends, her family, and her perfect pink-and-yellow bedroom were mine.

The series was cancelled after one season. It had been put into a difficult time slot, up against perennial favorites like The Beverly Hillbillies. Later, when the summer rerun season rolled around, and Americans were looking for fresh programming, many younger viewers tuned in to reruns of Gidget and liked what they saw. Summer was Gidget’s natural element and the show climbed up into the top 10 of the Nielsen television ratings. Alas, it wasn’t enough to save the show, but it dispelled the notion that America had rejected the program, and the show remained popular in reruns for decades. Many cultural commentators have proclaimed Field’s Gidget the best of them all.

In the decades after Gidget was cancelled, Field would establish a reputation as one of the finest film actresses of her generation, a reputation she still holds. Sandra Dee would not be so lucky, or perhaps she just wasn’t as strong. In any case, the abuse she suffered as a child led to longterm battles with anorexia, alcoholism, and depression. By the end of the 1960s, her film career began to sputter out. She made her last film appearance in 1983. After that, she became a bit of a recluse, and an unhealthy one at that. She died in 2005 at the age of 62. Though she played the part of Gidget only once, Dee was memorable in the role. The film has its flaws, but Dee’s performance isn’t one of them. Nonetheless, by the 1970s, she had become a bit of a joke—a poster girl for sexual repression, as evidenced by that catchy song in Grease:

Look at me, I’m Sandra Dee,

Lousy with virginity.

Won’t go to bed till I’m legally wed,

I can’t, I’m Sandra Dee

In the 1978 film version of Grease, the song is sung by bad girl Betty Rizzo (Stockard Channing) to mock clean-cut Sandy Olsson (Olivia Newton-John). One can only imagine how the lyrics might have read if Sandra Dee had kept her birth name, Sandra Zuck. The male lead in Grease is called Danny Zuko, so the first name of the female lead (Sandy) and the last name of the male lead (Zuko) combine to form a stealth reference to Sandra Dee.

As noted, Gidget seems to have been influenced by the Françoise Sagan novel Bonjour Tristesse, which had been published just three years earlier. Both books are about teenage girls spending the summer on one of the world’s most desirable beaches, falling in love, and getting their hearts broken. Both books are narrated in the first person, some months after the action has concluded. In the very first paragraph of Kohner’s novel, Gidget tells us of the book she is writing, “It’s probably a lousy story and can’t hold up a candle to these French novels from Sexville but it has one advantage: it’s a true story on my word of honor.” In 1956, when Gidget was written, Bonjour Tristesse was the French novel from Sexville that every literate American had heard about. The Los Angeles Times’ original review of Gidget called the book: “Midsummer madness about beach bums, surf boards, Malibu, and a 15-year-old American answer to Françoise Sagan.”

Sagan (whose real name was Françoise Delphine Quoirez) was born in 1935, and so she was of the same generation as Kathy Kohner. In case the connection between Sagan and Gidget wasn’t direct enough, Frederick Kohner lets us know that, in the summer of 1956, while stuck at home for a week with tonsillitis, Gidget spent her time alternately lost in an imaginary love affair with Moondoggie and reading a brand new Sagan novel, A Certain Smile, which was published in the US on August 16th, 1956. In fact, Gidget reads it three times during the week she is laid up in bed.

Like Gidget, A Certain Smile is about a teenage girl who develops an erotic passion for an older man. Naturally, the French novel, though tame by today’s standards, is far more adventurous than Kohner’s. Gidget, however, doesn’t understand its heroine, Dominique, who abandons a boyfriend roughly her own age to take up with the much older (and married) Luc. “Imagine letting a doll like Bertrand go to waste on account of an ancient lush like Luc.” After reading A Certain Smile three times, Gidget begins re-reading, for the sixth time, James Jones’s From Here to Eternity. She assures us that she doesn’t actually re-read the entire novel, just “the dirty passages.” Kohner clearly seems to have been impressed with Françoise Sagan, who was just 18 when her first novel was published. Even Gidget’s real name—Franzie or Franziska—seems to be a nod towards Françoise. William Dean Howells once criticized the appetites of his countrymen by noting that, “What the American public wants is a tragedy with a happy ending.” In Gidget, Kohner gave Americans what they wanted, a happier version of Bonjour Tristesse—a Bonjour Bonheur, I suppose.

Although the Gidget films no doubt struck beatniks and hipsters of the era as hopelessly square and middle-class, Kohner’s novel is much less so. In fact, it bears a slight resemblance to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which was published in September of 1957, one month before Gidget. The motto of the Go-Heads—“Early to bed, early to work is strictly for those who’ve gone berserk”—sounds like something Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty might have embraced. All the action in Gidget takes place in Malibu, but Kahoona himself is a somewhat Kerouacian character—a surf bum with no fixed address who travels around the world looking for big waves. His motto, we are told is: “The only way to gain economic independence is to be independent of economics. The more money you make, the less independent you are of it.” In the novel, Kahoona remains true to his vagabond lifestyle to the very end. On the last page of the book, Gidget tells us, “As for the great Kahoona: he had to fold up his stand after the fire and now he’s probably pushing some green water down in Peru…” Alas, Hollywood couldn’t embrace such an iconoclastic character. By the end of the first Gidget film, Kahuna has given up his surf bum lifestyle and taken a job as an airline pilot (apparently he learned to fly planes in the US Air Force during the Korean war).

In both the book and film versions of Gidget, Moondoggie, though his father is a wealthy oilman, aspires to give up bourgeois living and follow Kahoona’s itinerant lifestyle. Gidget tells us that, “His old man would have gladly sent him to some private college but all Jeff did was flip the bone at his old man which is a very dirty way of telling somebody where to get off.” At the end of the book, however, Moondoggie is at a military boot-camp in Texas. This seems likely to be the first step on a path that will take him back to a conventional upper-middle-class lifestyle, although the reader can still hold out some hope for him. In the film, Moondoggie is last seen picking up Gidget at her home. He’s dressed conservatively, driving a flashy convertible, and his surfboard is nowhere in sight. He seems to have already sold out to mainstream notions of success.

But Hollywood’s biggest betrayal of Kohner’s book concerns Gidget herself. Just prior to the film’s final scene, Gidget has a heart-to-heart talk with her mother up in her bedroom. Mom wants Gidget to give up all the surfing nonsense and follow the advice of an old sampler, stitched by Gidget’s grandmother and hanging on the wall above Gidget’s bed: “To be a real woman is to bring out the best in a man.” The end of the film makes it clear that Gidget will heed that advice. The last time we see her, Gidget’s beachwear is gone and she’s wearing a frilly white dress. Already she is preparing to become Mrs. Geoffrey Matthews, respectable housewife and mother. Betty Rizzo would howl.

But that is not at all how Kohner’s novel ends. Four pages before the end of the book, Moondoggie and Kahoona are on the beach at Malibu, engaged in a fistfight over Gidget. She considers stepping in to break it up but doesn’t think that’s likely to work. “So I did the next best thing to give vent to my soaring spirits. I lifted the board in my hands over my head and ran down to the water.”

All summer long, Gidget has longed to shoot the curl of a really tasty wave, but she’s only been able to accomplish this feat when riding tandem with another surfer. But now the surf is up and the waves are as high as houses. Gidget lies down on her board and paddles out beyond the breakers. By the time Moondoggie and Kahoona realize what she’s doing, it’s too late for them to catch her. She’s never gone out into the surf by herself before, and they begin frantically screaming at her to return to shore. But Gidget is having none of that.

No I wouldn’t go back. Not for the life of me. … A few more strokes and I was beyond the surfline. I couldn’t see the coast any more, so high rose the wall of waves before me. I whirled around and brought the board in position. There was no waiting. I shot towards the first set of forming waves and rose.

Gidget finds herself being lifted up onto a monster wave. She rides down the face of it and remains standing on her board, something she’s never accomplished before.

I was so jazzed up I didn’t care whether I would break my neck or ever see Jeff again—or the great Kahoona.

I stood high like a mountain peak and dove down, but I stood it.

The only sound in the vast moving green was the hissing of the board over the water. A couple of times it almost dropped away under my feet, but I found it again and stood my ground.

“Shoot it, Gidget. Shoot the curl!!”

My own voice had broken away from me and I could only hear the echo coming from a great distance.

“Shoot it…shoot it…shoot it, Gidget!”

There was the shore, right there. I could almost reach out and touch it.

Gidget would seem to be an intellectual property ripe for rebooting. You wouldn’t have to remake her as a feminist, because the original book has a feminist story arc. The character is, in some ways (though certainly not temperament), similar to Wednesday Addams. Wednesday debuted in a New Yorker cartoon on August 26th, 1944, three and a half years after Kathy Kohner was born, although she wasn’t given a name until she became a TV character. (Gidget lacked a surname in her first incarnation and Wednesday lacked a first name in hers.) Wednesday debuted as a TV character on Friday, September 18th, 1964, on ABC Television. Gidget debuted as a TV character almost exactly one year later, on September 15th, 1965 (a Wednesday, curiously), also on ABC Television. (Gidget begins on July 4th, 1956, also a Wednesday.) Wednesday Addams has no fixed age, but in her most recent incarnation, for Netflix, she is 15 when the series begins, the same age as Gidget in the first novel.

But, unlike Wednesday Addams, whose character was rebooted in the 1990s and in every decade since then, no official Gidget spinoff has come to the big or small screen since the 1980s. Also unlike Wednesday, Gidget probably couldn’t be easily updated for the 21st century. A 15-year-old girl who spends an entire summer hanging out with a bunch of sex-crazed males, all of whom are at least five years older than she is, would be a hard sell in 2023. To make Gidget any older would be to essentially abandon her true character—the word “girl” is baked into her nickname. The world of the mid-1950s also seems essential to her nature. The “midget” part of her nickname would be considered politically incorrect these days, but in the 1950s, it was just a bit of innocent fun. Likewise, surfing is no longer the exotic, outsider activity it was then. To properly resurrect the character, you’d have to keep her in her original milieu: Malibu in the mid-1950s.

A reboot could be interesting. But an update? Not so bitchen.