Art and Culture

Little Liliths

Contemporary feminist thought is correct to identify the male gaze as the default way of seeing, but has largely overlooked the fact that the gaze places power squarely in the hands of women, not men.

It’s Friday night. My teenage daughters have a group of friends over for a sleepover party. They’re making TikTok videos. I watch them watching themselves, dancing and giggling. They are admiring themselves. I can see the burgeoning femininity in them, their newly discovered sexual charm. They can see it, too. It is, in fact, exactly this that they’re looking for in themselves. They’re nurturing it, cultivating it, and as they do so, they feel their power increase. They finish dancing, and then sit together in a cuddle pile on the sofa, watching and rewatching their videos. They laugh at each other and at themselves, they tease each other, but they also compliment each other, telling each other how pretty they are, how well they move. They see this in each other but especially in themselves. It is a beautiful thing to behold, young adolescent girls loving each other and themselves. They choose the best videos from their drafts, which are often then heavily edited, to share publicly, displaying themselves to their friends and strangers alike. They are, in fact, objectifying themselves, turning themselves into little moving pictures, to be gazed upon and judged and appreciated. It is precisely this objectification that they want: their desire is to be desired.

In his foundational 1972 book Ways of Seeing, John Berger describes what is now commonly known as the “male gaze.” “Men look at women,” he writes. “Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relationship of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object—and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

Though we commonly understand the gaze as a demeaning form of male control over women, Berger’s real message isn’t that men objectify and govern women, it is that women control how they are perceived by first objectifying and governing themselves. The gaze causes a woman’s self understanding to be split in two: she must occupy a masculine perspective in order to maintain control over how she is seen, and consequently how she is treated. “Her own sense of being in herself,” Berger writes of women, “is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another.” This dual way of being oneself and of seeing oneself is precisely what my daughters and their friends are discovering as they dance in front of their TikTok screens. The girls don’t simply watch themselves; they watch themselves imagining how they are being watched by others. By having this dual vision they can calibrate precisely the effect of a swaying hip, a twirl, and a sultry glance at the camera.

Contemporary feminist thought is correct to identify the male gaze as the default way of seeing, but has largely overlooked the fact that the gaze places power squarely in the hands of women, not men. The young teenage girls in my basement, along with most of the other teen girls on TikTok, are expert in controlling how others will see them because they first see themselves in this way, as desirable, sexy, sweet, cute, hot, innocent, seductive, or alternately, as unsexy, serious, asexual. Men are subjected to how a woman sees herself: how can they not see a woman as a sexual object when she first creates herself as such? Berger is wrong to state simply that men act, for sight is something that acts upon them. To prevent his eye from alighting on a young woman who nurtures her own desirability with the craft of the average young teen, how can a man act but as he does: gazing, desiring, sexualizing? There is something ruthless in the girls’ looks, a hardness which accompanies their sense of growing power. Sometimes this is in conflict with their youthful innocence, and at other moments it adds a sharper flavor to their beauty.

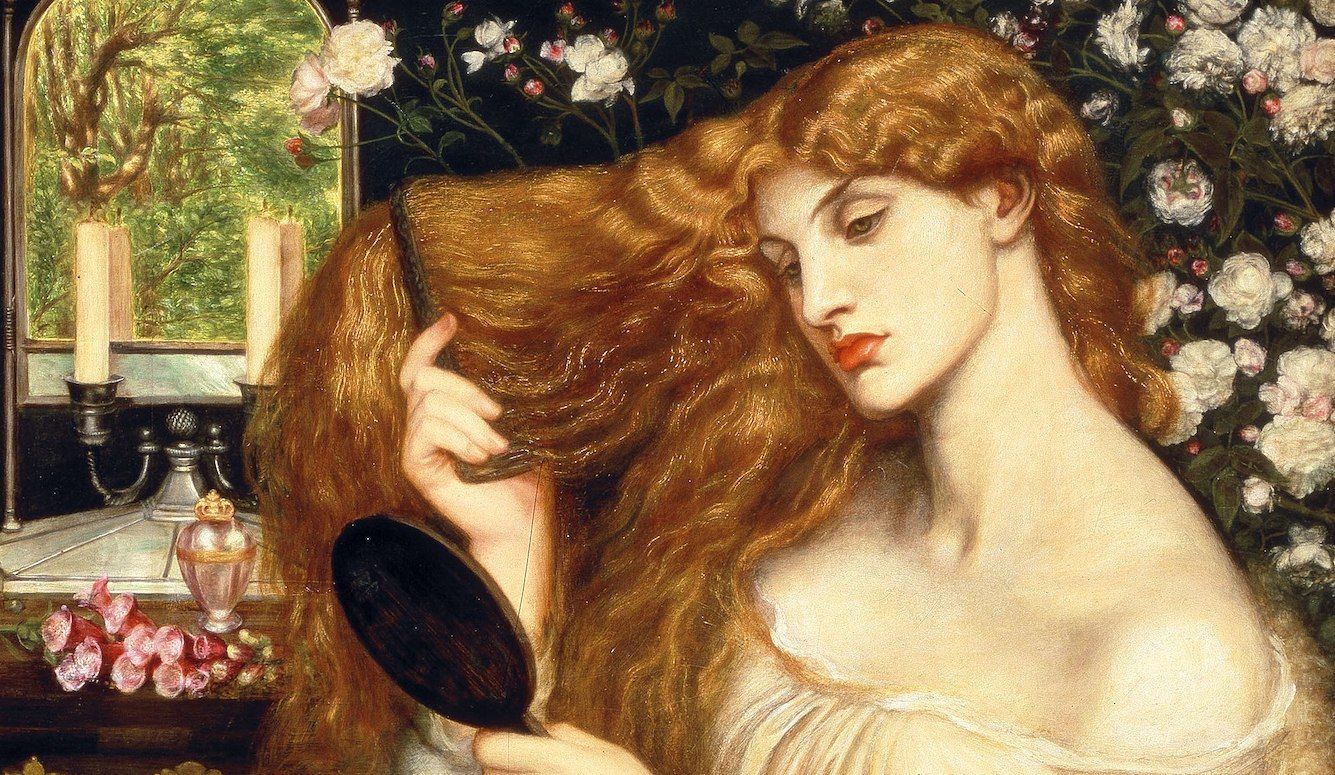

Consider the 19th-century painting with which Berger prefaces his discussion of the male gaze: Félix Trutat’s “Nude Girl on a Panther Skin” (below). The painting depicts a reclining female nude in the foreground and a man’s head leering at her through a window. It is, upon first glance, a familiar iteration of a woman being sexually objectified by a man: she is on display for his viewing pleasure. He is free to inspect her as he wishes, desire her at his leisure.

But a closer look suggests another interpretation. The woman is, first, the source of light within the painting. There are almost no shadows on her supple skin; the light seems to radiate from her rather than alight upon her. Her body is itself radiant. The eye is drawn to her, compelled to gaze upon her, whether one wills it or not. She is not merely naked, she is nude, and deliberately so. She has arranged herself so as to exhibit her beauty in the most flattering way possible. The line of her arm, torso, legs, toes is seamless and soft. One wants to run one’s fingers up the length of her leg over her slender waist to her inviting breasts. Her left breast is positioned so that we see the shape of its small, firm nipple, illuminated against the dark background. A bedsheet is draped over her hip and disappears into the fold between her legs where her sex lies, tantalizingly hidden. The crumpled folds of the sheet are shadowed and dark, suggesting both the idea of pubic hair and the dark secret of her opening, an opening that the slightest movement might reveal. The female: proof that there is a god, and that he loves us.

She is looking directly out of the painting towards us. Her expression is sultry. Her eyes are languid, but bored rather than welcoming. She is indifferent to her audience. She wants us to look at her but shows no sign of reciprocal attraction. She is complete in herself and seems to know that our wills are not entirely our own: her posture suggests that she has an interest in co-opting our eyes, yet her expression is one of profound coolness. There is nothing about her that suggests frigidity, but clearly desire here goes only one way. We might reasonably conclude that her position, carefully arranged to show herself to greatest advantage, has been painted merely to gratify the observer of the canvas: she must submit to the discerning gaze of the viewer, exposed, while we possess her as an object of sight and stand comfortably, fully clothed, before her. The male gaze is power over her.

This reading would be compelling, were it not for the male head looking in through the window of our nude’s bedroom. At first, one might interpret his presence as the domineering male gaze and the embodiment of power. The man is in fact a version of the men in Susanna and the Elders paintings, an Old Testament story in which two men, fully clothed, spy upon a woman bathing and then accuse her of infidelity when she refuses to have sex with them. (The story, incidentally, ends with the men getting justly punished and put to death.)

Yet Trutat has complicated this familiar narrative of a man’s power over a woman by his tricks of perspective. In the painting, the man’s head is at least twice the size of the woman’s. He’s a giant. He may be able to drink up his fill of looking, but the small window frame through which he gazes is not large enough to let him into her room, except perhaps with great difficulty. Besides, he is all head. His body, the instrument with which he might hope to satisfy his desire, simply isn’t present. If this man is supposed to be the embodiment of power, he is remarkably unembodied. His gaze might penetrate, but that’s all that will. His brow is furrowed. You can see his concentration upon her, but also his frustration. He cannot look away—why would he want to?—but nor can he find release from his longing. It is she, the source of light, who controls his eyes. If we consider that both the leering man and us, the viewers of the painting, are gazing upon her, we might come to realize that we are explicitly aligned with him. And our position becomes one of discomfort. We are, like him, transfixed by her luminous body but without any hope of satisfying our desire. The painting does not present the male gaze as a look of power, but rather of powerlessness. He cannot choose but look. And she knows it.

The growing awareness of the erotic power represented in Trutat’s painting is on display in my house as the teenage girls dance and sway and giggle. They are not in the least bit interested in the boys or men who might be watching them. They are interested in their own beauty and sexiness. “The beauty of the female is the root of joy to the female as well as to the male,” wrote CS Lewis. “To desire the desiring of her own beauty is the vanity of Lilith.” This quote, from Lewis’s science fiction novel That Hideous Strength, distills the Instagram/TikTok phenomena, much derided among progressives and conservatives alike, that sees girls and women catering to the male gaze (progressives hate this) by sexualizing themselves (conservatives hate this). Lilith is a late-antiquity mythological character, Adam’s first sexual partner, a woman of fiery lust. She is a she-devil banished from paradise for her disobedience and her licentiousness. The legend of Lilith has only gained in popularity; she has become, variously, a menacing figure that embodies the demonic nature of feminine sexual power, or a heroine of contemporary feminism, celebrated for her unholy sexual power. In both cases, dangerous or powerful, she is a figure who uses her sexual capacity as a tool or as a weapon to assert her control over others, for good or for ill.

But what if, quite simply, there is a naturalness in a little Lilith’s admiring self-gaze. It isn’t merely for the sake of growing in power or control that a woman admires herself, it may be because her own beauty gives her joy. And it may also be that Lilith is a stage in development rather than an aspiration. She is, after all, a kind of proto-Eve, not fully woman. Seen in this light, the self-admiration which accompanies a teen’s social-media performance is a healthy, perhaps even a necessary, part of her development towards erotic maturity and the fulfillment of her desires.

Contemporary feminism instinctively valorizes a woman’s sexual power and also criticizes men’s sexual objectification of women. But these things cannot be disentangled. A woman’s desire to be desired is her sexual power, the power of Lilith. If it exists in isolation, as it does on social media, it may serve to give a woman the joy of her own beauty. But this comes with a cost: it encourages her to first objectify herself in order to control how she is then perceived by others. As a result, she is caught in this paradigm of self-objectification. The upside of this is that she experiences the pleasures of being desired, which is a pleasure of control. The downsides are not only that this control is often illusory (we are all familiar with the well-catalogued mental-health ailments that afflict teens), but that she is also lonely. The woman in Trutat’s painting may be in full control of the male gaze, but she cannot move past herself into sexual pleasure. The desire of her own longing consigns her to an unfeeling, cold existence, gazing at herself as though through our eyes. The problem in turning herself into an object of desire isn’t that it’s debasing, it’s that it’s boring. The vanity of Lilith is not merely that her desires make her vain, it is that it is done in vain. Hers is a fruitless sexuality.

The complete passage from Lewis reads, “To desire the desiring of her own beauty is the vanity of Lilith, but to desire the enjoying of her own beauty is the obedience of Eve, and to both it is in the lover that the beloved tastes her own delightfulness.” It is an arresting conclusion. The word “obedience,” especially when it comes to a woman sexually delighting a man, feels strangely like a violation rather than a compliance. Something is being transgressed. Her will? Her decency? Her self-respect? Social codes? Modern agency? It isn’t exactly clear, but what we do know is that a woman’s sexual obedience feels wrong. Which is why it is so tantalizing.

Eve’s obedience is not due to a man. It is due to herself, to her own nature. It is to the desiring of her enjoyment that shows Eve’s obedience. Obedience is the fullness of her desire. For Eve, the enjoyment of her beauty is exciting. It thrills because it offers the chance for real touch and pleasure, and, more importantly, because it is only in obedience that there is genuine freedom. Eve is freed from self-gazing to become wholly embodied rather than cooly calculating. Hers is the freedom of sexual ecstasy.

We think instinctively that the opposite is true, that the opposite of obedience must be disobedience, and that only disobedience makes us free. But disobedience and obedience may mean simply following our own inclination; we may comply or not as we’d prefer in the moment: we may simply be indifferent to all but ourselves. But obedience is doing something we may not want to do precisely because we are told to do it. It is deliberate. It is the act of being radically free because it involves a real assertion of will and agency. It is more than surrender. Obedience is for adults. The vanity of the little Liliths who dance for their TikTok videos knows nothing of the strength that accompanies assent, nor the thrill that comes from obeying freely. The culmination of a woman’s erotic power is to joyfully surrender it to a man for his enjoyment precisely so that she may taste her own deliciousness through him.

Of course, one shouldn’t say such things in polite society. And that is exactly why it is such fun to say such things. Nothing is so naughty as obedience. This is also what makes it dangerous. To desire the enjoying of one’s beauty as a form of obedience is to put oneself in great risk. It is to make oneself open to degradations and humiliations. One’s humanity may be ignored, or even defiled. Obedience is not for the faint of heart. It shouldn’t be toyed with by the young and inexperienced, which is why for them the game of playing for the camera is the innocent vanity of girls. Bravo, little Liliths, I say! Claim your power. But then… what are you going to do with it? What is power for?

It might be simply said that power gives one pleasure. Pleasures come in many forms and most of it is secondary, such as power leading to the acquisition of material resources. But there is also a more direct connection between pleasure and power, as Nietzsche famously said, “Happiness is the feeling of power increasing.” When it comes to a uniquely feminine erotic power, we can appreciate the power that comes with simply controlling the male gaze. This means she delights in having others see her as she herself has determined to be seen.

On the other hand, if a woman’s delight in her beauty occurs through her lover, then her greatest pleasure is to enjoy herself through him. This is a radical departure from the dialectic of power. For a woman to obey the authority of her own beauty is to move beyond the pleasures of power to the pleasures of the body itself. She triumphs over the push and pull of men’s and women’s desires for power by joyfully relinquishing control. To desire as a mature woman, fully in possession of her erotic power, is to desire more than self-admiring vanities. It is to taste of her own power in the act of giving it away so that it may be enjoyed. Quite simply, her own pleasure is itself the act of love.