Nations of Canada

The World of the Iroquois

In the third instalment of an ongoing Quillette series, historian Greg Koabel describes the revolution in agriculture, politics, and war that would transform many Indigenous societies before the arrival of French explorers.

What follows is the third instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialized project adapted from transcripts of Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name, which began airing in 2020.

In the first instalment of this series, I mentioned that there were three dramatic moments of change in Canadian history before the cataclysmic event of prolonged European contact. The first was the development of culturally sophisticated hierarchical societies on the west coast. Next came a series of migrations in the Canadian arctic, which (by the 13th century) resolved itself with the Inuit holding sway in the far north.

The final development that we’ll focus on this time is perhaps the most important—both because it sparked truly revolutionary economic and social change, and because it established a geopolitical balance of power that would guide the next two centuries of Canadian history. The arrival of the Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries will, of course, feature prominently in our story. But until the English and French came in greater numbers, the course of events was determined by the powers we’ll encounter today.

The catalyst for change was the introduction of agriculture to the portion of southern Ontario bounded by the Great Lakes, and the upper portion of the St. Lawrence River. This was a slow process, beginning around 500 AD and reaching full maturation in the 13th century (as the Inuit were consolidating their hold on the Arctic). Before this period, all societies within modern day Canada were hunter/gatherers (even the highly successful fishermen of the west coast). The Iroquoian speakers of southern Ontario were the first to grow crops, which quickly re-shaped their societies into entirely new entities.

The story of agriculture in the Americas was part of a larger global movement, but with distinct local characteristics. Like elsewhere in the world, the impetus for agriculture appears to have been some event, around 13,000 BC that released high amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This was absorbed by plants, which became rich and plentiful. In various places around the globe, humans took advantage, and began to experiment with domesticated plants. That’s the theory anyway, and it’s the best explanation we have for why agriculture developed nearly simultaneously in several different places across the globe.

The agricultural revolution in the Americas seems to have started in modern day Mexico. First came squash, followed by other gourds, beans, and avocados. But the real breakthrough came around 5,000 BC with the domestication of corn—a massively efficient food delivery system. The grains used by European farmers in the 16th or 17th centuries tended to produce six times the amount planted. In especially fertile soil, perhaps this ratio could be improved to 10 to one. Corn, on the other hand, could produce returns as high as 150 to one.

For a long time, the origins of corn were a bit of a mystery in the world of botany. Only recently have scientists been able to identify the origin point of domesticated corn in teosinte (a species of wild grass). What has always been clear is that corn (while incredibly efficient) is temperamental. In its domesticated form, it cannot reproduce without the aid of humans, and was likely the product of more than a thousand years of painstaking trial and error in selective breeding.

From its origins in modern day Mexico, agriculture fanned out across the Americas. By 500 AD, corn reached the northern limits of its livable habitat—the Great Lakes. It could not thrive in the rocky soil of the Canadian Shield, and there were not enough frost-free days for a crop to take hold.

This portion of southern Ontario and western Quebec was the home of the Iroquoian speakers—a distinct language group from the Algonquin speakers who occupied the Canadian Shield to the north and the Maritime provinces to the east, down the St. Lawrence River. In addition to language, the adoption of agriculture by Iroquoian speakers became an important distinction between them and the Algonquin-speaking hunter-gatherers.

However, despite all my talk about revolutionary change, corn did not immediately alter life among the Iroquoian speakers. At first, agriculture merely complemented the existing subsistence techniques of hunting and fishing. Growing and harvesting corn was likely seen as akin to the gathering of nuts and berries that women had always done.

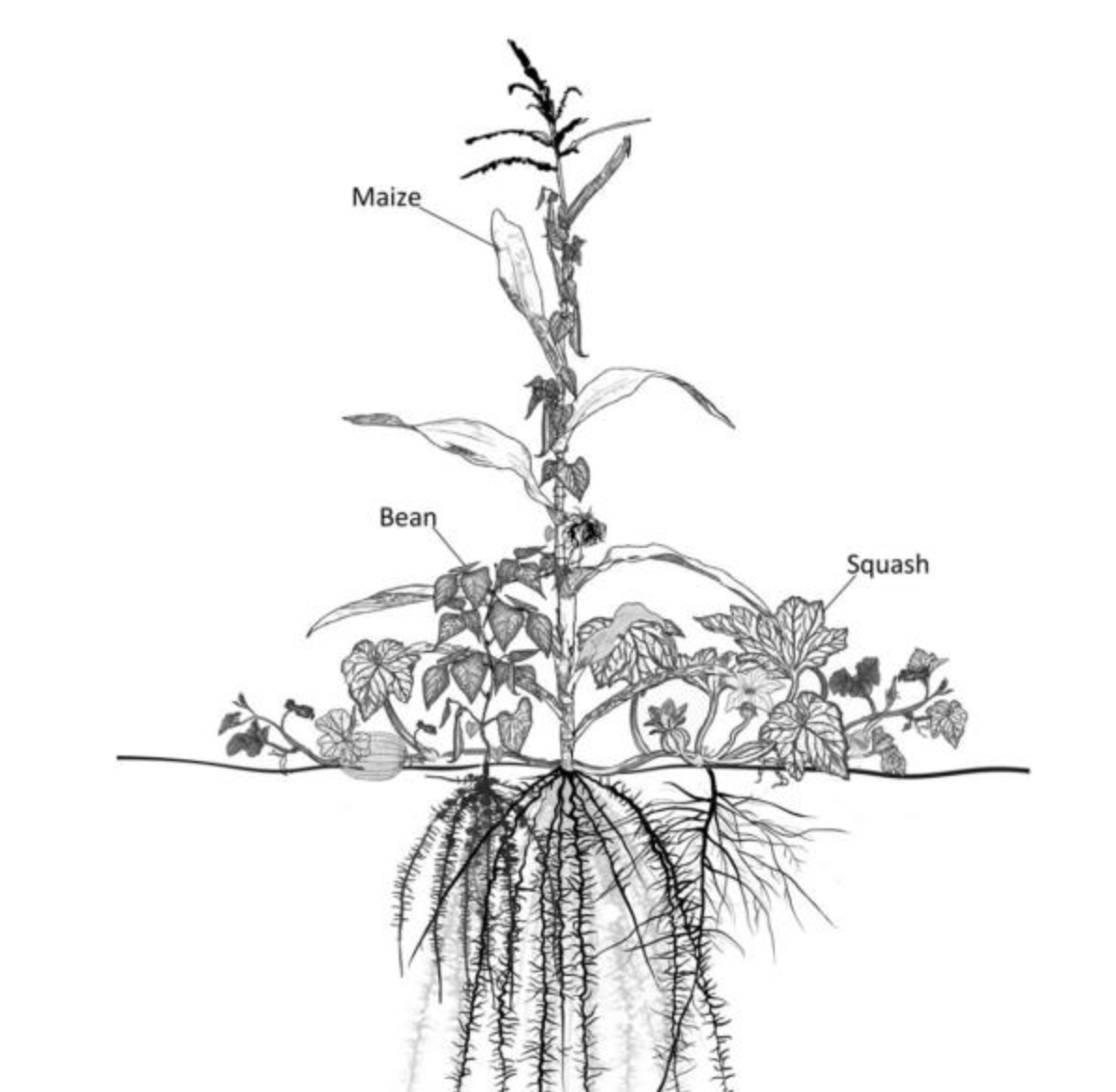

It was only over time that corn became a larger and larger part of the diet. This was accompanied by greater agricultural sophistication, especially the introduction of new crops that complemented the growth of corn. The most important of these were beans (introduced around 1000 AD), and squash (present in the area by 1200 AD). In fact, the Iroquoians referred to these crops as the “Three Sisters”—an unbeatable team that provided each other with mutual reinforcement.

All three were planted together. The corn stalks provided beans with a pole to climb, while the beans strengthened the stalks against harsh winds (while also capturing nitrogen in the soil). Meanwhile, squash shaded the base of the stalks, preventing any weeds from getting sunlight. The Three Sisters were also complementary from a dietary perspective. Corn provided the base carbohydrates, beans the protein, and squash produced important vitamins.

Once all three Sisters were in place (roughly the 13th century), agriculture took over as the dominant method of subsistence. Radical social change began almost immediately.

The most obvious change was in where people lived. Like most Canadians, up until this point, the Iroquoians had divided their time between seasonal camps. In the summer, large groups gathered at known fishing grounds, while in the winter they divided into small groups and spread out into hunting territories large enough to sustain a nuclear family.

But with corn cultivation now the focus of economic life, it made sense to live in villages permanently anchored to the fields. Energies were devoted to the crop, with the stored surplus providing food for the winter (which could be supplemented by the hunt).

However, it should be said that “permanent” is a relative term. Iroquoian farming villages tended to have a shelf life of 10 to 30 years. That was because of the slash-and-burn method of agriculture they adopted. Establishing a farming village required the clearing of forest. Stone axes were used to fell smaller trees, while larger ones were “girdled” (a method of killing a tree by removing its bark in a ring near the trunk). Over time, the tree dies, and its branches fall off. Once enough trees were removed, the resulting land was rich in nutrients and open to sunlight.

But eventually, over the course of years, the quality of the soil degraded. So too did local game populations, depleted by the high population density of the village. Iroquoian villages were therefore on the move about once a generation. This has been a boon for archaeologists, who get to catch a glimpse of Iroquoian life in roughly 25 year chunks. (In comparison, seasonal fishing settlements that were re-used by tribes for thousands of years produce a confusing cache of artifacts that can be very difficult to date.) As a result, we are able to track the changes in Iroquoian society along an unusually precise timeline.

These villages also tended to be bigger and better organized than in the past. Previously, whole communities had gathered at established fishing grounds. But these settlements had been temporary, and could perhaps rely on only informal or ad hoc responses to the conflicts or disputes that inevitably arise from people living together.

Nuclear families organized into larger extended lineages. These relationships were formalized by the defining feature of the Iroquoian village—the Longhouse. Running the length of the longhouse was a central corridor, in which fires could be built. Family apartments were created by walling off cubicles on either side of the corridor (so each fire was shared by two families, one on either side). The size of longhouses grew over time, with the rise in population. Or I should say the length of the longhouses grew: New apartments could be tacked on to accommodate growth. Usually these expansions could wait until a new village was constructed, but in periods of rapid population expansion, multiple extensions were needed in one cycle.

A village consisted of several longhouses (anywhere from 30 or so, to over 100 in the larger villages). The longhouse also acted as a kind of political unit, with men chosen to represent the lineage in its relationships with other longhouses. Village politics was marked by discussions between such representatives that (as we’ll see) became more complex over time.

It should be noted that these representatives were not necessarily figures of authority. They had no ability to coerce anyone, and could be removed if they attempted to do so. It’s more accurate to think of them as representatives rather than rulers, imbued with prestige rather than power.

But perhaps the most significant consequence of adopting agriculture was the resulting change in gender relations. Before the arrival of agriculture, the division of labour among the Iroquoian speakers was much like that in the rest of Canada. Men hunted and fished, while women gathered nuts and berries. At first, things were not radically altered by the introduction of corn. Women naturally took up agriculture as a sub-division of their gathering duties. But as the corn harvest came to dominate economic life, the relationship between the genders inevitably shifted.

The most dramatic change came in how lineages were defined. Previously (as with most indigenous societies), lineages were built around the male line, and brides went off to live with the tribes of their new husbands. But now, women were the economic backbone of the community, too valuable to be lost in marriage. As a result, the system reversed itself. After marriage, it was men who left home, to join the extended family of their new wives. Lineages were now determined by descent through the female line, which meant that those extended longhouse families were linked by a matriarch, rather than a patriarch.

The political effect of these changes was not quite as pronounced, however. The leaders who represented their kin in village discussions were exclusively male. But they were selected from matrilineal networks (often a leader would be succeeded by his sister’s son rather than his own). And in some Iroquoian societies, women had the power to select and remove these representatives.

In terms of impact on our narrative, the changing roles for men were just as important as the increasing economic and social prominence of women. Intuitively, it would seem that a greater role for women would mean a diminished role for men. But that would not be entirely accurate. Men did not tend to the crops, but they did play an important role in the corn industry. Clearing the forests of the Great Lakes region was hard work, especially if you don’t have access to iron tools. And the procedure of relocating a village to a new site was a long process that had to be started well before the move-in date. Forest clearing and construction was a job that now made up a significant chunk of a man’s duties.

There was also one crop that men (and only men) were responsible for—tobacco. Every step of tobacco production and consumption was an exclusively male affair, imbued with spiritual meaning. Smoking tobacco allowed one to disconnect from this world, and enter another one, usually only accessible in dreams. The fact that the tobacco in question had as much as four times the nicotine as modern cigarettes suggests that this was a realistic goal.

As the hunt declined in importance relative to corn, however, men lost an important venue in which they had previously won prestige. Some men, especially young ones seeking to make a name for themselves, turned to a new opportunity to stand out—war. This trend was facilitated by the larger communities that agriculture produced. Like the hierarchical societies of the west coast, larger populations and greater social organization allowed for organized violence.

From around 1200 to 1500, these various forces unleashed by the corn revolution re-shaped the Great Lakes region. Until this period, the effects of agricultural adoption had been muted. Corn probably accounted for roughly 10 percent of the overall diet, and the rhythm of life was still largely seasonal. Summer settlements were starting to be chosen for soil and drainage rather than proximity to fishing sites, but communities still dispersed in the winter. Summer villages were also still quite small, probably on average consisting of less than 100 people.

Change came suddenly though, with the adoption of the Three Sisters system of corn, beans, and squash, around 1200. Villages shot up in size, on average doubling or tripling in population. The shift from women leaving home to join their husbands, to husbands leaving to join their wives also appears to have started in this phase, an indication of the economic importance of experienced women farmers. The geographic spread of corn began taking off. The first farming communities had emerged on the Grand River, which flows south into Lake Erie. Now the practice began to expand eastwards, across the north coast of Lake Ontario towards the St. Lawrence, and northwards, toward Georgian Bay.

The spacing between villages suggests that hunting grounds were the determining factor in this dispersal. The greater concentrations of population required large hinterlands to ensure an adequate supply of game and skins.

The 13th century produced a century-long period of continuous growth, and it was capped off by a huge population explosion in the first decades of the 14th century. Where previously villages had doubled in size in a century, they doubled again in less than 30 years. In part, this was due to the surplus food the adoption of agriculture produced. But more influential was the amalgamation of smaller villages into larger ones.

This process of village consolidation does not appear to have been driven by economics. In fact, the larger villages were noticeably less efficient since women had to travel further to tend to the fields. The high-intensity farming used up the soil far quicker, and the higher population density depleted local sources of game much quicker, too. Which meant more frequent relocations, an unwelcome burden on the labour force.

So if economic necessity did not drive the move to larger villages, why did so many smaller villages join together?

The answer appears to be the need for security. The agricultural revolution brought with it more highly organized violence, as with the hierarchical societies on the west coast. This follows the general pattern that the more sedentary and socially organized a society is, the greater it its ability to devote resources to war. But the nature of the agricultural revolution among the Iroquoian peoples seems to have created a particular spur to violence: As the male hunt declined in economic importance, and women dominated the primary economic activity of agriculture, the easiest remaining avenue to win male prestige was war.

The oral traditions of the Iroquoian people generally refer to this period as a chaotic and violent time, when war was unrestrained by any inter-tribal rules of hospitality or order. Larger villages were easier to defend than smaller ones, especially when they were protected by the impressive wooden palisades that became common in this period.

The concentration of more and more people into single villages (and the common threat of the outsider) spurred on greater developments in social organization. Along with the villages themselves, longhouses doubled in size too, signalling that the social unit of the lineage had somewhat expanded to include a wider range of kin. Longhouses also became more neatly arranged within the village, rather than haphazardly constructed, suggesting more structured relations between lineages.

It seems that in this second phase of the corn revolution, between 1300 and 1330, Iroquoian villages passed a threshold beyond which old, informal systems of social organization based on direct family relationships no longer sufficed. Where previously, individual lineages had been able to live and work together in a largely unstructured way, now conflicts and disputes were frequent enough that some kind of system was required to maintain order in society.

This developing system of social organization was based on a formal elevation of matrilineal heritage links. Each longhouse built its collective identity around a matriarch, either through direct descent, or marriage. Households also selected spokesmen to represent the lineage in village politics, usually in the form of an official council, populated by representatives from each longhouse, as well as a collection of respected elders.

But by itself, this structure was not really sufficient to bind the community together. So households also fit into an over-arching structure of fictive kin relationships—in other words, a large community (known as a clan segment) that was united by a common ancestry that could only be vaguely traced by blood links.

Each clan segment adopted a symbol, usually an animal, by which to identify itself. This helped bind villages together, by giving households a larger community to belong to (rather than each one standing on its own). Clan segments also helped link villages to one another, as a single clan segment could exist in multiple villages.

Clan segments were led by chiefs—usually two, in fact: One, to manage civil affairs, and another war chief, to lead the people in arms. Again, these were not authoritarian positions. War chiefs could not order anyone to fight, but rather had to convince their fellow clan members that the cause was just. Similarly, civil chiefs were more diplomats than rulers, often chosen for their charisma and oratorical skills. In both cases, chiefs were typically chosen on their merits, but the pool of candidates was usually restricted to the men of an elite matrilineal line.

The result of these clan segments was an over-lapping network of relationships that provided opportunities to resolve disputes before they turned violent. An individual might take a grievance to his household leaders, who would in turn bring it to chiefs of the clan segment, who could then represent the aggrieved party in the larger community.

This system fell short of the kind of centralized state structure that was increasingly common in Europe—a fact that would lead to no end of confusion and misunderstandings in the future. Clan chiefs or village leaders had no coercive authority. The council did not pass legislation that subjects were bound to follow. Clan segments remained self-regulating bodies. Internal matters weren’t the business of outsiders. The apparatus was really only used to resolve disputes between groups, or to make collective decisions. A key point here is that those collective decisions were determined exclusively by consensus. Unless everyone could be convinced of one course of action, the collective would not act.

As I say, this would lead to all kinds of frustration for Europeans, who treated chiefs and other political leaders as the authoritarian rulers that Europeans were used to, when they were not.

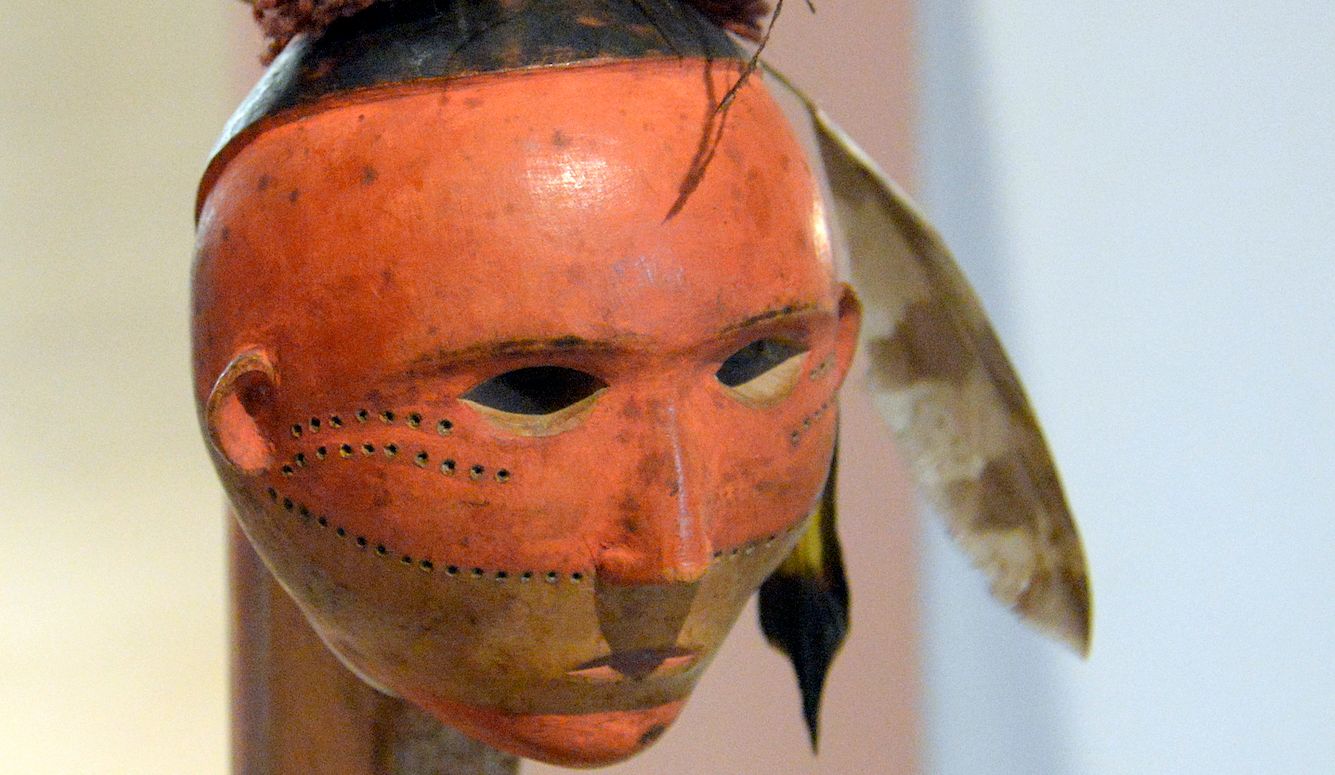

In addition to creating systems of political organization, Iroquoian speakers also tackled the problem of social cohesion through culture. Rituals of hospitality blunted the edge of inter-tribal violence, and reinforced membership in the village community. The most important of these rituals was the Feast of the Dead, a 10-day ceremony that marked the re-location of the village. Everyone who had died since the village was founded (no matter which clan segment they belonged to) were exhumed and reburied in a common ossuary. With the community moving on, the dead could now finally begin their long westward journey, toward the next life.

In addition to sending the dead on their way, the ceremonies served community-building functions. The common ossuary represented the shared identity of the villagers, no matter their affiliations of kinship. Clan and village leaders distributed gifts, reinforcing their elevated social status. And neighbouring dignitaries were often invited to participate, confirming friendly relations through the exchange of gifts.

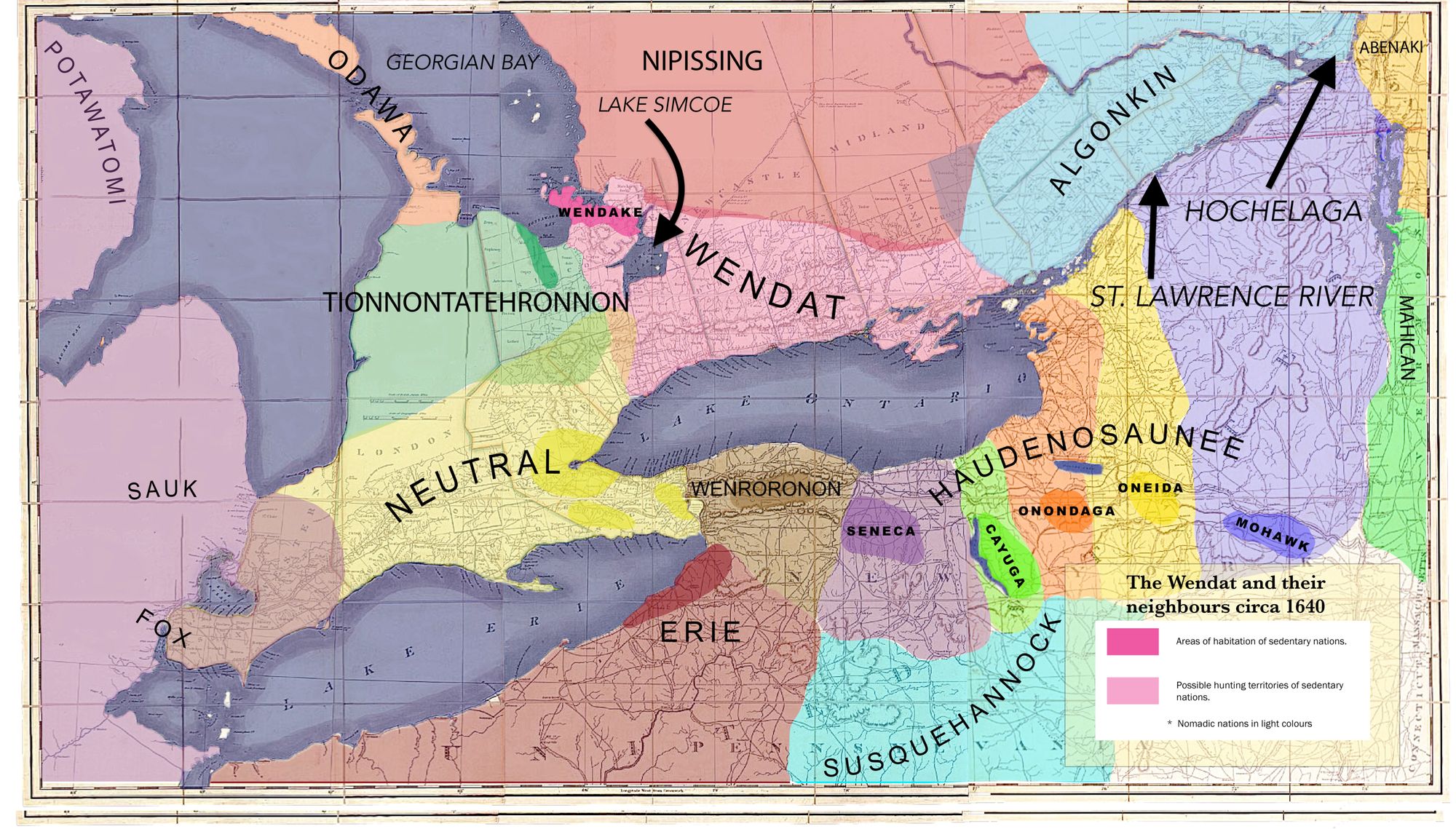

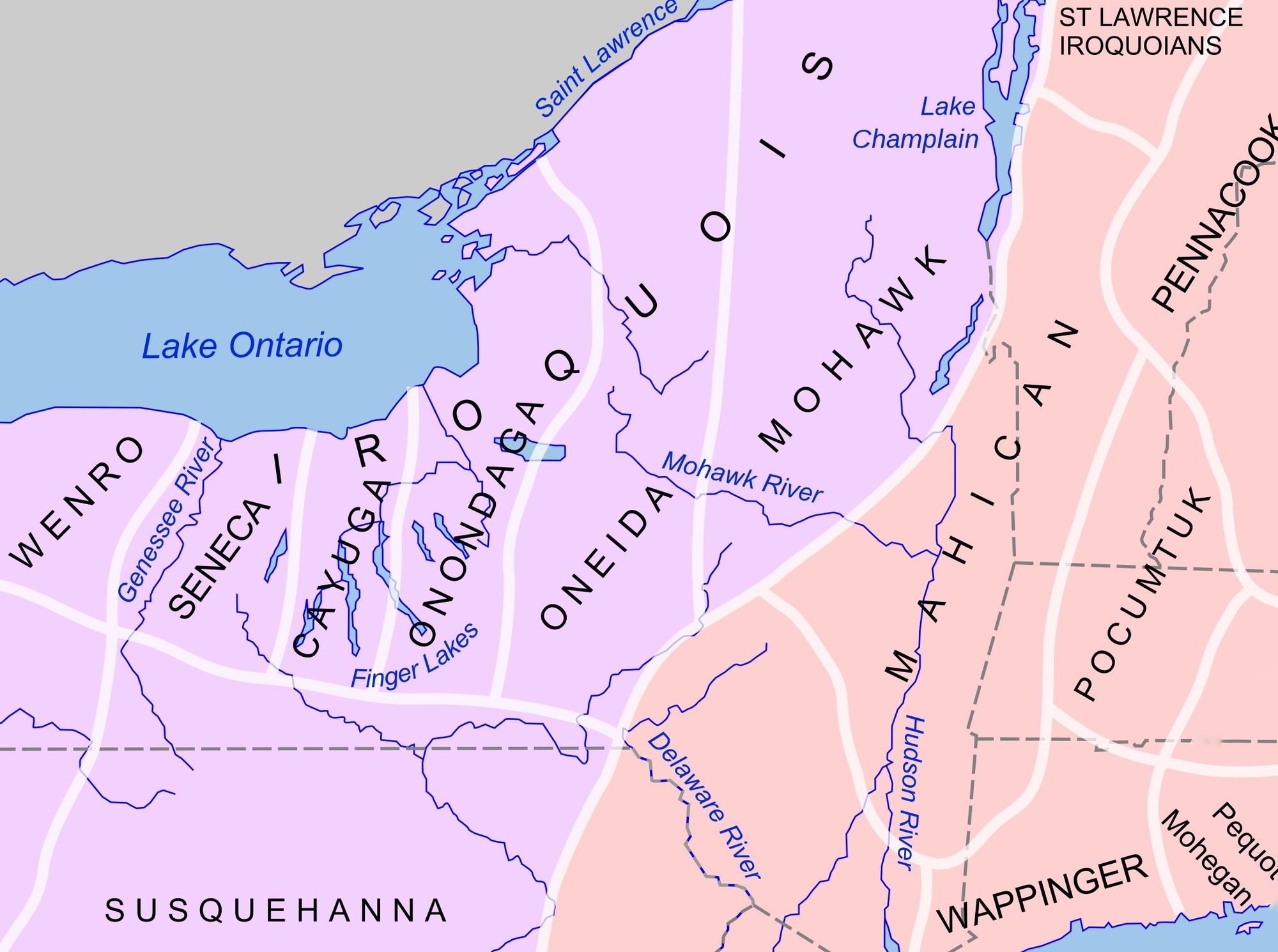

The high growth rate and greater sophistication of social relations continued throughout the 14th century and into the next. By the 1420s or so, the Iroquoian peoples had spread the agricultural revolution to the natural limits of corn cultivation, marking a rough line between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay. From there, the cornfields moved south to the shore of Lake Erie, then across the Niagara Escarpment into present day upstate New York, on the south shore of Lake Ontario. From there, it reached an eastern line along Lake Champlain, and up to the mighty St. Lawrence River. In effect, various Iroquoian-speakers occupied modern day southern Ontario, northern New York, and south-western Quebec.

These territorial boundaries, and the villages within them, would be roughly the same encountered by the first European explorers. A normal village might have a population of around 2,500 (though some were quite a bit larger). Longhouses were, on average, around 50m long (though some pushed 100m). The great population boom levelled off a generation or two before the arrival of the Europeans, possibly due to the end of the geographic expansion. Population estimates can be quite erratic, but the absolute low end for the region as a whole is around 60,000 people in 50 or 60 villages. In all likelihood, the number was probably higher than that.

Over the course of the 15th century, a distinct Great Lakes political landscape emerged. Some villages banded together into confederations, to facilitate peaceful relations between one another, and join together for defence. The relationships and rivalries between these confederations would end up exerting a tremendous influence in the two centuries after European contact, and so it is worth spending some time on them now. (The Europeans, of course, had their own impact on the course of events, but the story of the early European explorers, traders, and settlers would be incomprehensible without understanding the geopolitical situation they encountered in eastern Canada.)

The various Iroquoian societies and confederations all had their distinct characteristics, but we’ll start with their common economic, political, and cultural traits. The pattern of slash-and-burn agriculture and single generation villages was common throughout the area. However, on the eastern margins, as you moved down the St. Lawrence River, the line between farmers and hunter-gatherers got a bit blurry.

There were broad cultural commonalities. For instance, the Feast of the Dead was a shared ritual, and would have been comprehensible to all. But, in terms of communication, we’re talking about an Iroquoian language group, not a shared language. Some languages were mutually incomprehensible, creating the requirement for pidgin trade languages between some tribes.

It’s worth dwelling on why the Iroquoian peoples fought wars. Conquest does not appear to have been a motivating factor. In most conflicts that we know of, there’s little evidence that the goal was to displace the enemy and take over their land. War parties often ranged quite far from home, and the success of their missions was measured by enemies killed and prisoners taken, not the seizure of land. Neither did competition over commerce appear to have been an important factor in war. In the past, there was some speculation that after the arrival of Europeans, competition over the lucrative fur trade instigated a wave of violence across the region. But it’s now clear that persistent war pre-dated the trade routes formed by the arrival of the Europeans.

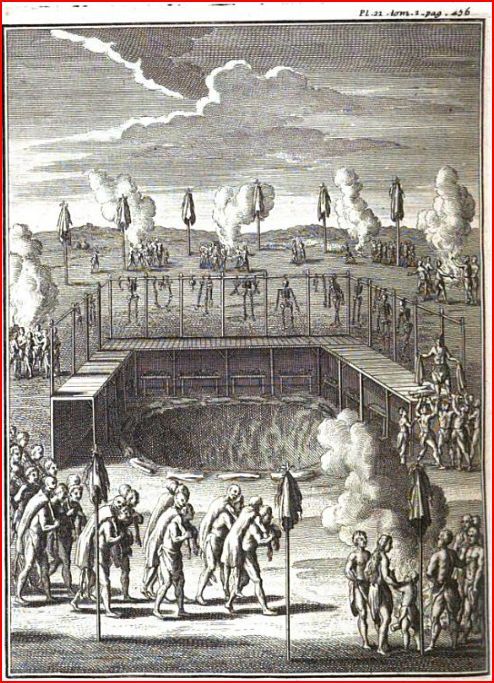

War seems to have been driven by the need of men (especially young men) to make a name for themselves, or to exact retribution for past wrongs. It seems the process of amalgamation and social cohesion had mostly re-directed violence from conflicts within the community, into well organized violence enacted far from home. Warriors who returned from battle with plenty of prisoners to ritually torture and kill won great prestige among their neighbours.

Again, this was an unfamiliar and confusing dynamic for the first European explorers, accustomed as they were to wars of conquest, religion, and economic competition. What to a Frenchman might seem like senseless barbarism, was, to an Iroquois warrior, the natural development of centuries of context. Archaeologist and historian Bruce Trigger points out that while Europeans often found the torture of prisoners barbaric, the Iroquois had a similar reaction to the elaborate torture and execution rituals of the European justice system. Both societies were comfortable with torture, in the proper context.

So who were the major players in 15th and 16th century geopolitics in the Great Lakes region? The first thing to note is that there were several groups that will not be the main stars of our narrative. And it is precisely for that reason that we don’t know that much about them. As they were not deeply involved in interactions with Europeans, we have little in the way of documentary evidence of their activities. For the most part, we’re relying on archaeological evidence and second-hand accounts from Europeans. For instance, the Petun Confederacy, which occupied the south shore of Georgian Bay, roughly from modern day Owen Sound to Collingwood. Or the Erie Confederacy, located on the south shore of Lake Erie up to the Niagara River.

Perhaps the largest of these groups was the so-called Neutral Confederacy (the label itself being an indication of why we know so little about them). Samuel de Champlain, one of the most thorough chroniclers of early 17th century Iroquoian politics, named them the Neutrals because they were not involved in the main rivalry between the Wendat and the Five Nations Confederacy. It’s possible the Neutral Confederacy (located on the Niagara Peninsula) was the largest group in the Great Lakes region, with over 30,000 people (though most historians give that title to the Wendat Confederacy).

These confederacies all have their own story, though they are more difficult to reconstruct, and are secondary to the international saga that would play out within eastern Canada over the next two centuries. As a result, they’ll mostly remain in the background of our narrative.

The same cannot be said of the Iroquoian speakers who lived along the St. Lawrence River to the east. Although much smaller than the Neutral Confederacy (with a population only totalling about 8,000 in the region), they would be the first Iroquoian-speakers to encounter Europeans, and as such played a disproportionate role in events, considering their numbers.

The agricultural revolution seems to have arrived on the upper St. Lawrence later than in the southern Great Lakes. But by 1300, corn was being cultivated as far east as modern day Quebec City. As well as being late adopters, the easterners were only partial adopters. Fishing remained an important part of economic life, especially for those furthest east.

In fact, the settlements along the river acted as a kind of agricultural spectrum. The westernmost village, Hochelaga (near present day Montreal), relied heavily on corn, just like any number of villages around the Great Lakes. Hochelaga was also a single, consolidated village, well defended by a palisade, with an architectural style similar to what could be found in Ontario.

Over 200 km further downstream, was Stadacona (a village that had one foot in the agricultural world of the Iroquoian-speakers, and another in the hunter/gatherer traditions of the Algonquin-speakers). The Stadaconans farmed corn, but they also went on a massive annual fishing expedition to the mouth of the St. Lawrence, a legacy of the seasonal migrations that defined life before the arrival of agriculture. Their villages were also spread out along the north bank of the St. Lawrence, prioritizing economic efficiency rather than security. This is an indication that Stadacona was on the eastern periphery of the Iroquoian world. Organized warfare did not often reach that far down the river.

Which isn’t to say the Stadaconans were unfamiliar with violence. There is evidence that they often tussled with the Algonquin-speakers whose lands they travelled through on their annual fishing expeditions (Mi’kmaq on the Gaspé peninsula or Innu on the north shore). But this was more in the vein of rival hunting parties clashing with one another, rather than systematic warfare.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians (as these Hochelagans and Stadaconans are collectively known) would be the first to make contact with Europeans, a full 60 years before the other Iroquoians. So we’ll be meeting them again soon.

But we’ll conclude with the two heavy hitters of the Iroquoian world: The Five Nations Confederacy (also known as the Iroquois Confederacy), and the Wendat Confederacy (also known by the name the French gave them—the Huron). These two rivals created a centre of gravity in the Great Lakes that drew in their neighbours and (eventually) the Europeans.

The Five Nations Iroquois Confederacy was formed out of (you guessed it) five Iroquoian nations, probably some time in the 1450s. To avoid confusion, I will note that the language group that all of these corn farmers belonged to was the Iroquoian language group. But the term Iroquois, in this context, refers to the people of this particular confederacy.

The Five Nations (with a total population of around 16,000) occupied the northern portion of modern day New York state, running from the Genesee River in the west to Lake Champlain in the east. From west to east, the five were the Seneca, the Cayuga, the Onondaga, the Oneida, and the Mohawk. These were a diverse collection of five nations that retained their own distinct identities within the confederacy. In fact, the languages spoken by the western Seneca and the eastern Mohawk were mutually unintelligible. Each member of the confederacy had its own interests and enemies. By European standards, this was a very decentralized political organization.

The Five Nations Confederacy is unique among the Iroquoian Confederacies in that it still exists today (albeit in a different form). As a result, there is an oral tradition to draw on in piecing together the initial formation of the confederacy. When combined with the archaeological evidence, this gives us a useful picture of the 15th century Iroquois.

By tradition, the Confederacy was formed in response to the period of chaos and violence I mentioned earlier. Some form of inter-tribal organization was required to limit conflicts and provide collective security against those outside the group.

The impetus for these alliances came from an obscure visionary named Dekanawideh (or “Heavenly Messenger”). Dekanawideh grew up in modern day Ontario, on the opposite side of Lake Ontario from the Iroquois homelands. It’s possible his mother was one of the many people displaced by war. As an adult, he travelled to the lands of the Onondaga with a message of peace. One of his first converts was Hiawatha, a great warrior who prospered in the world of violence, but had begun to question its effect on his humanity.

However, aside from Hiawatha, the Onondaga were not receptive to Dekanawideh’s message. In particular, the great chief Atartaho saw any political change as a threat to his power. Dekanawideh and Hiawatha fled and spent the next few years spreading their gospel among the neighbouring nations. Dekanawideh was the ideas man, but seems to have had limited skills as a public speaker, possibly due to a speech impediment. Hiawatha therefore acted as spokesman for the movement.

Over time, the pair successfully presented a case for a peaceful coalition. Their first converts were the eastern Mohawk, followed by the Oneida and the Cayuga. Bringing in the western Seneca took longer, but (aided by a dramatic eclipse of the sun), they too were brought on board. (There was an eclipse visible from the area in 1451, leading historians to date the origins of the confederacy to the mid-15th century. That timeline roughly accords with the archaeological evidence.)

The final challenge was the Onondaga and their powerful war chief Atartaho. The combined forces of the Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca faced off against Atartaho and his warriors. But rather than do battle, Hiawatha managed to talk Atartaho into joining them. Atartaho seems to have been convinced by the military threat the growing coalition posed, not to mention Hiawatha’s offer to make him the overall chief of the Confederacy.

The details of the legend are unprovable in a historical sense, but its spirit is consistent with other historical evidence. The formation of the confederacy was likely motivated by incessant warfare and the need for a mechanism to resolve disputes between villages and nations. The process would have been a drawn out and gradual affair, with each nation conducting its own negotiations, balancing cooperation and autonomy.

The result was a decentralized political organization, which sat atop existing forms of village and tribal governance. A council of 50 chiefs (drawn from the clan segments of all five members) met annually. Inter-tribal disputes were settled, and outside threats were discussed, though any communal decision had to be made by consensus. The Confederacy only really considered inter-tribal affairs. What went on within each member’s society was its own business.

The Iroquois Confederacy was probably not the first inter-tribal coalition. (A generation or two earlier, the Neutral Confederacy emerged on the Niagara Peninsula.) But the Iroquois Confederacy had a dramatic impact on the course of events around the Great Lakes. In the decades after its formation, there were several large-scale movements of population in the region. The Neutral and Erie Confederacies both moved westward; the Wendat pulled back from the coast of Lake Ontario and concentrated in the north around Georgian Bay; the St. Lawrence Iroquoians moved further down river; and the Susquehannock (a people to the southeast of the Iroquois) moved further away, towards the Chesapeake and Atlantic coast.

Two aspects of these sudden migrations are significant. First is that the one group that did not budge was the new Iroquois Confederacy. And the second is that all of these groups were moving away from the Iroquois homelands. The conclusion historians have come to is that the Iroquois Confederacy very quickly emerged as a military power, forcing neighbours to retreat into more defensible territory. Though, that may over-simplify what was happening. For instance, there is evidence suggesting that the St. Lawrence Iroquoians were more threatened by Wendat warriors than those of the Iroquois. But the foundation of the Iroquois Confederacy does seem to have been a catalyst for the division of the Great Lakes region into political units, separated by quasi-neutral zones.

By the time Europeans arrived on the scene in the 16th century, this had become the new normal in the Great Lakes region. The geographic and demographic expansion had settled into an equilibrium.

We’ll end with the Confederacy that would become the main rival to the Iroquois within this equilibrium—the Wendat (who, as noted above, would eventually be known to the French as the Huron).

The Wendat Confederacy probably began around the same time as the Iroquois Confederacy, as a coalition between two nations—the Attignawantan and the Attigneenongnahac. The Attignawantan was the larger of the two, and would remain the dominant force in the confederacy even as it expanded its membership.

In in its origins, the Wendat Confederacy likely shared many similarities with the Iroquois Confederacy. Its function was to preserve the peace through institutions and ceremonies that bound its members together. Both confederacies also created an infrastructure through which disputes could be resolved amicably.

But the Wendat Confederacy differed in two important ways.

First, while the members of the Iroquois Confederacy continued to live in their traditional homelands, the Wendat Confederacy was as much a place as a political coalition. The term “Wendat” meant those who dwell on the island, or the peninsula. This referred to the Wendat territory which was bounded by water on three sides: Georgian Bay to the west, Lake Simcoe to the east, and the marshy border with the Canadian Shield to the north. Membership in the Confederacy entailed moving into this region. The constituent tribes of the Confederacy remained distinct entities, but their villages and cornfields were concentrated in a single territory.

The second feature of the Wendat Confederacy that set it apart from that of the Iroquois was its relationship with its neighbours. In particular, its neighbours to the north. The Wendat Confederacy was located in the northern borderlands between the agriculturally friendly Great Lakes region, and the Canadian Shield. As a result, the Wendat had much more direct contact with Algonquin-speaking hunter/gathering societies that the other Iroquoian peoples.

Inevitably, this sometimes led to conflict, but the Wendat Confederacy was self-consciously designed to facilitate trade with the Algonquin speakers. The surplus of corn the Wendat produced was highly valued by the hunters (as their own food supply could be unpredictable and precarious). In exchange, Wendat traders received meat and skins. These were valuable to the Wendat, as their sedentary lifestyle and relatively high population density depleted the stock of local game. The Wendat were also more accomplished fishermen than hunters.

Tracking pre-European trade routes is difficult work (especially as most of the goods exchanged—furs, for instance—have not been preserved for archaeologists the way stone or pottery would be). But judging by future events, it seems likely that the Wendat had mature trade relationships with the Nipissing people to the north (who lived around Lake Nipissing, the western end of the east-west Ottawa River valley trade route). They also dealt with the Ottawa people—who, confusingly enough, did not live in the Ottawa River Valley at this time. They lived further north on the coast of Georgian Bay, and had their own trade networks that extended across to the western extremity of the Great Lakes.

The importance the Wendat placed on trade was evident in their legal traditions. In all Confederacies, the primary method of resolving disputes between members was gift giving. Rather than seeking revenge for past wrongs, proper balance was restored through generosity. Among the Wendat, however, this tradition expanded outside of the Confederacy. In fact, in the case of making amends for causing the death of a family member, the Wendat offered much larger gifts if the aggrieved party was a foreigner. This would seem to indicate the economic importance the Confederacy placed on trade relationships.

It also suggests the potential danger associated with trade. Small groups of Wendat traveled quite far into foreign lands, where they were at the mercy of the locals. Maintaining personal relationships was therefore key. Hard nosed deal-making existed alongside a culture of reciprocal gift giving and hospitality. In the future, this melding of a commerce and community would befuddle European traders who were single-mindedly devoted to profits.

Internal Wendat traditions were also geared towards trade. By custom, the clan segment that originally established a trade route retained a kind of monopoly on its future use. Other clan segments within the confederacy could trade along that route only with the permission of the monopoly holders (which was usually given after a suitable gift was offered).

The proceeds of these trade routes were distributed within Wendat society through lavish gift-giving ceremonies that won status and prestige for the traders. A central pool of resources was maintained by the Confederacy as a whole, for diplomatic gifts or in case of emergency.

Trade may also explain the geographic location of the Wendat Confederacy. Although the land was suitable for the growth of corn, the lands to the south and east (the north coasts of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario) were more fertile. In fact, during the formation of the Wendat Confederacy in the 15th century, the member nations actually retreated from these fertile lands and concentrated on the northern extremity of corn-friendly terrain, along Georgian Bay.

In part, this was likely motivated by a desire to put some distance between themselves and Iroquois war parties. But the Wendat Confederacy was larger than the Iroquois (with rough population estimates of 30,000 and 18,000 respectively). And there is ample evidence that the Wendat were more than capable of holding their own militarily.

Archaeologist Bruce Trigger speculates that the Wendat were drawn by the advantages of the north as much as they were pushed there by Iroquois aggression. Trade was once again the key: The Wendat territory was ideally placed along several key trade routes. By moving up the coast of Georgian Bay, Wendat traders could go west through the Great Lakes; north all the way to James Bay in the Arctic; or east along the Ottawa River.

Frequent encounters with Algonquin speakers may have also contributed to the Wendat sense of self. Unsurprisingly, they saw their sedentary lifestyle as superior to that of the hunter-gatherers to the north. The Wendat Confederacy was the wealthiest society in the known world. All too often, poor hunting seasons would leave the Algonquins dependent on Wendat corn.

While maintaining amicable trading relationships was important, that did not mean those relationships had to be equal. Algonquin speakers were expected to learn the Iroquoian tongues of the Confederacy, not the other way around. And while Wendat men could marry Algonquin women and bring them into the Confederacy, it was unthinkable for Wendat women to leave home and join an Algonquin husband in the north. Part of this, of course, has to do with the fact that the Wendat lived in a matrilineal society while the Algonquin speakers lived in patrilineal ones, but a sense of cultural superiority had a role to play, too.

Needless to say, Algonquin speakers put little stock in these Wendat pretensions to superiority.

And speaking of pretentions of cultural superiority, we are now prepared (in the next instalment) for the entry of Europeans into our Canadian story. The Iroquoian context we’ve covered in this installment is the same one those Europeans would encounter when they moved up the St. Lawrence. But it would take some time for these new explorers to penetrate that deep into Canada.

Next time, we start our story in the mid-15th century, around the time that the Wendat and Iroquois Confederacies were being formed, and the last Norsemen were leaving Greenland. While all that was going on, a group of fishermen in south-western England were on the prowl for new waters in which to ply their trade.