Indigenous History

Fictionalizing Māori History in the Name of Gender Ideology

Around the world, trans activists are cynically attempting to drape their faddish colonial theories in the garb of timeless Indigenous wisdom.

My organization, Mana Wāhine Kōrero (which translates as “Sovereign Women Speak”), was one of the two New Zealand groups that facilitated Kellie-Jay Keen’s visit to Auckland in March. We are a Māori (indigenous people of New Zealand) women’s organization and—as far as we know—the only gender-critical indigenous women’s group in the world. Our members are deeply concerned about the impact that gender ideology is having on our culture; on our wāhine (women); and on women’s rights more generally, as seen through the prism of Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview).

Following Keen’s harrowing experience in Auckland, few New Zealand media outlets accurately reported on the violent nature of the mob she faced. A notable exception was journalist Sean Plunket, an independent Kiwi radio host who has regularly endured criticism for questioning gender ideology (and identity politics in general). Following Keen’s mobbing, Plunket expressed both sympathy and shock, and gave over much of his airtime to the traumatized women who’d been at the aborted speaking event, including Keen herself.

On April 3, Plunket publicly challenged New Zealand Prime Minister Chris Hipkins to answer the question, “What is a woman?” Much to the dismay of many, Hipkins did not appear to have an answer. His stumbling response and panic-stricken facial expression soon became a viral sensation.

Sadly, the fact that the Prime Minister of New Zealand (not unlike politicians in other countries) cannot define a woman was not the main takeaway for many journalists. Instead, much of the media bashed Plunket, accusing him not only of being “anti-trans,” but also of “diminishing indigenous cultures” for posing the question at all.

And just how did Plunket serve to impugn “indigenous cultures”? The answer to that question was provided by someone called Ahi Wi-Hongi, the spokesperson for a New Zealand trans-rights group called Gender Minorities Aotearoa. In a (since deleted) article that appeared on New Zealand’s popular Stuff site, reporter Ripu Bhatia wrote that:

Wi-Hongi (Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāpuhi [the names of two Māori tribes]) said anti-trans rhetoric diminishes indigenous cultures. ‘Historically, Māori culture has included more genders than just male and female, and that’s going back a long, long way,’ [Wi-Hongi] said. ‘Pre-colonisation in Aotearoa [New Zealand], the human rights situation and gender equality was much more advanced than it was in the UK at the time.’

But my Māori women’s rights organization does not support the suggestion that Plunket deserves to be labelled as ignorant or racist. Rather, the attacks against him exemplify the tactic by which activists use bigotry accusations as a means to discourage any questioning of gender ideology by the general public.

Māori are not “one size fits all.” We do not, for example, all agree on the use of the word Aotearoa (“The Land of the Long White Cloud”) to describe New Zealand. There are 103 recognized Iwi (tribes) in New Zealand. To think that we are identical is simplistic.

Māori are similar in following the social hierarchy of Whanau (family), Hapu (sub-tribe), and Iwi (tribe). We have a common racial bond, a common tongue (albeit with regional and local variations), some shared knowledge, and revered whanau (extended kin group) history that is held by the elders. But this is typically where the similarities end. Each Iwi has its own whakapapa—history and genealogy. We have our own creation stories and tribal legends; and our own kawa and tikanga (kawa being what we do, tikanga being how we do it). Each Iwi has its own sense of self.

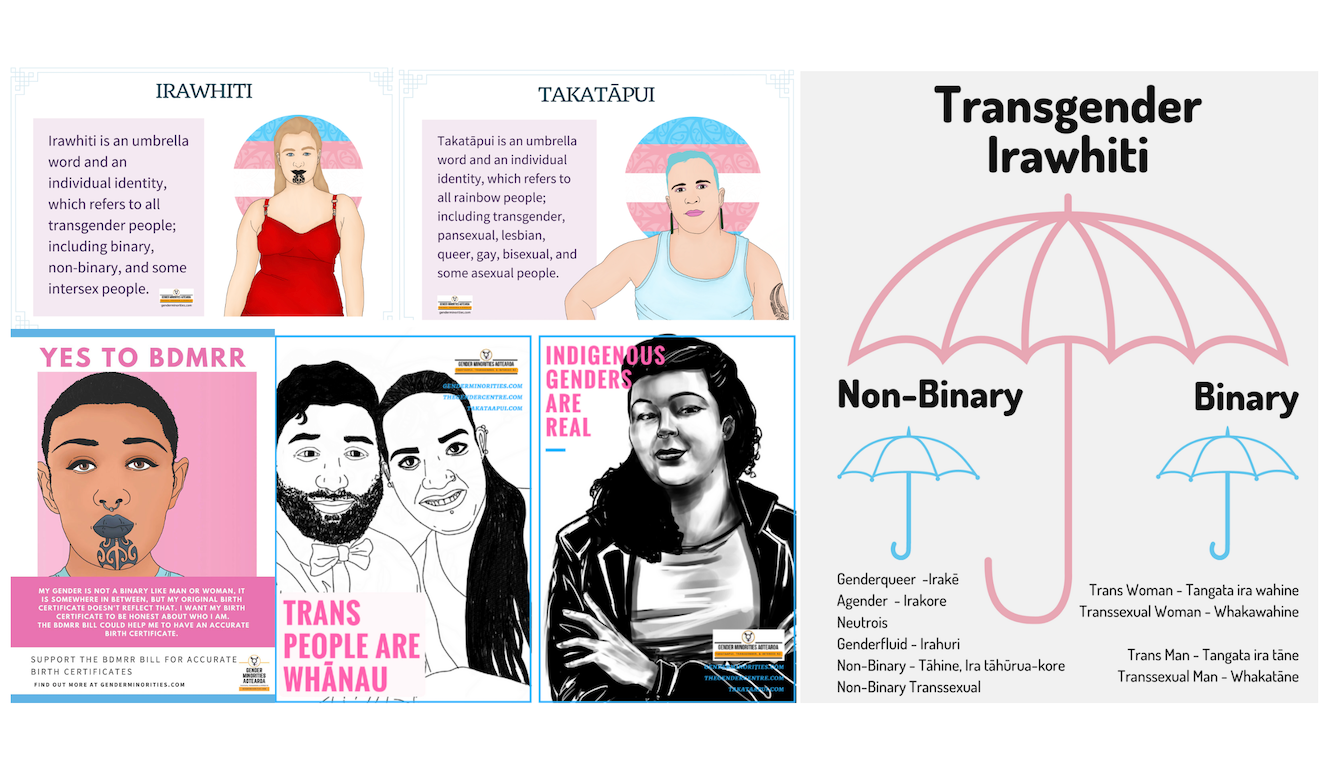

The arrogance required to take someone else’s history and claim intimate knowledge of it is quite staggering. While Wi-Hongi may be Māori, no one Maori person speaks for all of us. Certainly, “Gender Minorities Aotearoa” does not. The group does not even comprise an Iwi. It is merely a well-funded organization whose dubious activities include sending damaging breast binders to teenage girls, and inventing new words in Te Reo (Māori language) to describe wholly colonial conceptions of gender. In so doing, these activists are pretending that concepts such as “gender affirmation” have always existed in Te Reo. This is obviously contradictory: If these ideas had “always” existed, today’s activists wouldn’t have to invent new words for them.

Māori history, culture, and knowledge (mātauranga) are carried forth orally and visually through the generations—via stories, songs, proverbs, carvings, tattoos, and performing arts. These have meaning beyond artistic expression and technical skill; they tell the genealogies of individuals, families, and tribes that have gone before, and mark great moments in their histories. There are no examples of anything resembling western ideas about “gender” in any of these cultural traditions.

Nor are there any carvings, waiata (songs), or mōteatea (poetic tales of sadness, farewell, or grieving, put to music) dedicated to such themes. Not one mōteatea references the sorrow of a child “born in the wrong body.” However, we might sing one now, for those sterilized children who’ve been convinced to alter their bodies in the name of gender ideology; and for our wāhine Māori, the most incarcerated female demographic in the world, now being imprisoned with violent men.

Or consider Tā moko—tattoos that are distinct between men and women. Only wāhine may wear a moko kauae (chin tattoo). No Tā moko for “gender diverse” individuals have ever been recorded. There are no carved whare (houses) or tukutuku panels (decorative panels depicting historical events relevant to the tribe) that suggest gender as being anything other than binary and immutable.

There are no stories of any great trans warrior or chief. Nothing exists to say that we believed in double mastectomies for teenage girls or orchiectomies for our young men. The majority of the Māori words that appear on the Gender Minorities Aotearoa glossary of trans words were, by the authors’ own admission, “developed” only recently.

Meanwhile, older words such as takatāpui (intimate companion of the same sex) have been redefined by gender ideologues channelling a colonial mentality, co-opting the Māori acceptance of homosexuality into something that promotes the lifelong medicalization and even surgical disfigurement of our tamariki (children).

The cultural taonga (treasure) referenced by Wi-Hongi to back up the idea that Māori society embraced gender ideology tend to depict same-sex relationshops—i.e., Takatāpui, meaning homosexuality. These taonga do not represent proof of social transition, surgical intervention, chest binding, “gender affirmation,” or any other such euphemism. Homosexuality, almost by definition, does not require changing gender or sex; it is distinct from transgenderism.

The linguistic appropriation endorsed by Wi-Hongi and other activists is damaging our language—turning it into what some have called “fruit-salad Māori.” My elders do not understand the new form their language has taken; modern Te Reo is unintelligible to them. It is absolutely unnatural in Te Reo to disregard wāhine, as gender ideologues do. Wāhine were respected and had distinct roles and functions within the whanau. There are many whakatauki (proverbs) relating to wāhine. It is well known that several chiefs were wāhine. None were “gender fluid.”

There is a story, Te Awa Atua (the flow of menstrual blood; the river of the ancestors), that illustrates an important difference between the western concept of female power and its importance in Māori traditions. This is not my story to tell, as it does not relate to my Iwi. However, I was born in Pōneke (Wellington), and I was told this version on the land it happened on by the Mana Whenua (the Iwi of a particular area), so I will take the liberty:

There was a powerful tohunga (chosen or appointed one; an expert practitioner of a skill or art, religious or otherwise) hunting Te Rauparaha (a famous Ngati Toa Chief). So Te Rauparaha went to a village, and there he found the chief’s wife in the menstruation hut—and this is where he hid. The tohunga looked and looked, but he could no longer find Te Rauparaha. The power of the menstrual blood—Te Awa Atua; the river of the ancestors passed and unborn—shielded him from sight.

This is an example of how Western colonization affects our stories about wāhine. The tale should be about the power of women’s menstrual blood. But in recent decades, the retellings have instead emphasized the shame of the man hiding under the skirts of a woman.

Something similar is now going on with gender ideology, a global phenomenon that attaches itself to indigenous cultures, giving activists the illusion that they are promoting an authentic and antique form of enlightenment. Ahi Wi-Hongi is an example of this, picking and choosing parts of our culture, cobbling them together into a sort of raggedy patchwork cultural cloak to wear as justification for faddish beliefs; a cloak that bears no resemblance to the beautiful original stories of Māori.

But maybe the tide is turning. In recent years, Stuff has turned itself into a particularly strident defender of gender ideology. And so it is notable that even this publication was moved to remove the article about Plunket within just a few hours of posting it. Perhaps its editors now know that the activist’s claims cannot be substantiated, and that more and more Māori are becoming aware of the falsehoods being perpetuated in our names.

Mana Wāhine Kōrero vehemently opposes this rewriting of our culture, our language, and our history. Many children who fall prey to it will be unable to have tamariki of their own, ending our whakapapa forever. What better way to engineer us extinct as a people? In place of our culture will be only that raggedy patchwork cloak. This is why we will defy the gender ideologues who claim they are the experts on our history and our matauranga (cultural knowledge). We will resist them for as long as it takes.

To our New Zealand readers, we of Mana Wāhine Kōrero lay this wero (Māori challenge) at your feet. Who is brave enough to accept it?