Science / Tech

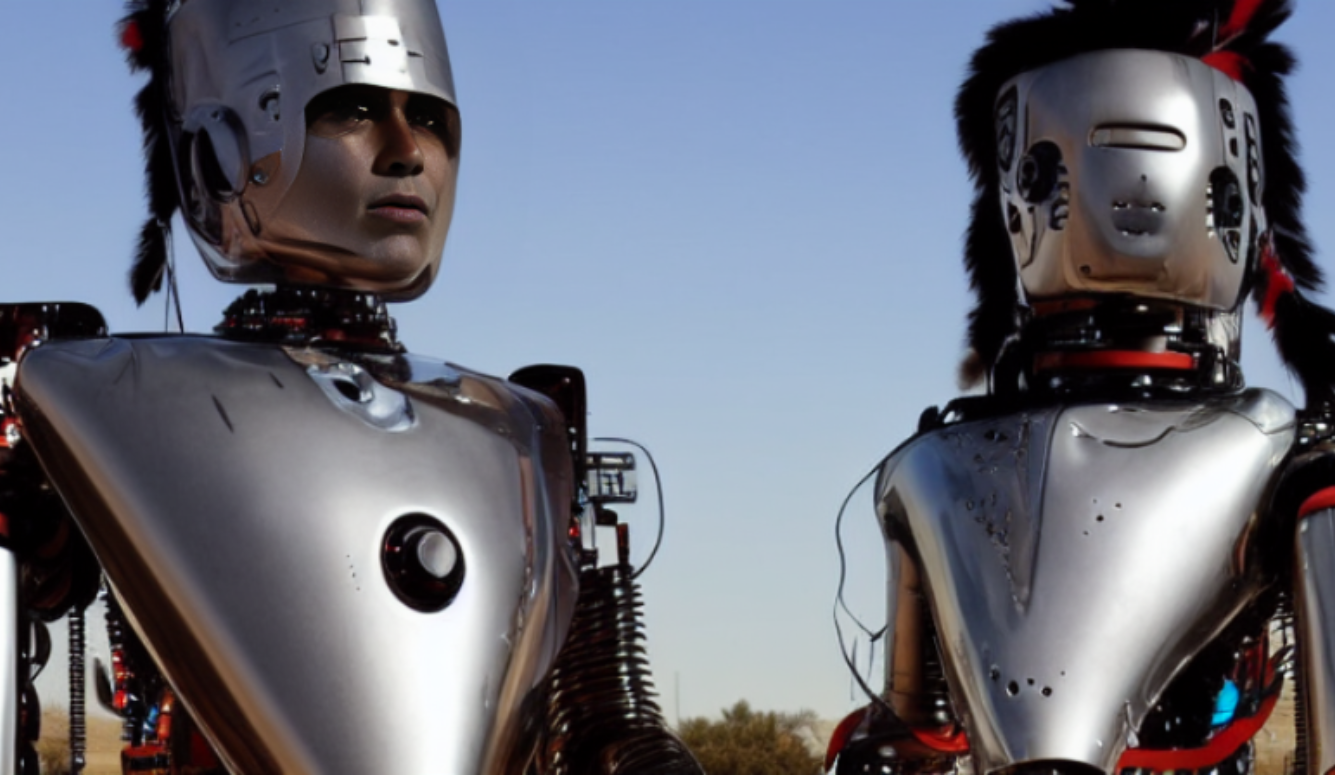

The Horseless Comanche

The new world of AI promises great peril but also great potential.

Artificial Intelligence, the Holy Grail of Computing, has received a good deal of advance hype in recent months, and the Extremely Online are extremely perturbed. In particular, ChatGPT, a programme which answers questions in coherent sentences, has the digital literati looking more pasty than usual. The Terminator is coming for tech jobs. Silicon Valley’s worker bees, who were sanguine about automation making redneck truckers redundant, are starting to panic.

Wired magazine, parish journal of the Church of Jobs, is pumping out a series of nothing-to-see-here articles to keep the flock calm. ChatGPT, according to staff writer Yunqi Li is “certainly not a monster that will destroy humanity.” It’s not? Oh good. The same gatekeepers scoffed when Elon Musk warned in 2014 that, “With artificial intelligence we are summoning the demon.” Last summer, they dismissed Blake Lemoine as a crank. Lemoine is the engineer Google suspended after he said the AI he was testing had demonstrated sentience. Damned inconvenient if your digital slave passes the Turing Test before you can sell it.

If the apocalypse really is looming in San Francisco, the rest of us have barely noticed—a mark surely of our bifurcated times. Civilians only spot these things when they spill into reality. Do you remember when you folded up your road map and started navigating by phone? Of course not. You never looked back. A similar revolution is now brewing with AI and art. And you don’t need to be fluent in Python to know something remarkable is afoot.

Like alchemists extracting gold from base metal, programmes like Midjourney, DALL-E, and Stable Diffusion, are suddenly and mysteriously creating art. It’s easy. Type in a prompt: “Ape flies zeppelin to Mars” and, hey presto, illustrations appear of a space-traveling simian. You can render your hellish vision of Martian monkeys in the style of Da Vinci, Duchamp, or Disney. I exaggerate—the software is buggy, with more misfires than hits—but a glimpse into this magic cauldron is enough to know that someone somewhere will soon make a packet. We are a visual species. Delight our eyes and the world is yours.

Not everyone’s chirpy about all this. At UnHerd, a publication in danger of becoming the hub for reactionary techno-terror, Mary Harrington is creeped out by the “mushroom-like” way AI mimics details while bungling the textures, rather like the pod people in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Her critique transcends aesthetics. Machine learning, Harrington warns, is “another step closer to a world ruled by machines; machines that are brilliant at detecting patterns, but idiots when it comes to understanding what those patterns mean.”

I’ve been only dimly aware of this growing discontent. As a bronze sculptor, I essentially live in the early Middle Ages. Still, on my last visit to the foundry, the resident tech bro showed me his Midjourney experiments. Days later, a flock of social-media posts appeared urging a boycott of these unholy apps. This call to arms came mostly from righteous souls who were on the warpath against NFTs last year. While that particular bogeyman has evaporated, AI seems quite a different beast, if not a hydra.

Computers making art causes frowns in the art world for the very practical reason that most artists today rely heavily on computers. It’s damn disconcerting. One day, you are happily using a tool. The next day, the tool tells you to clear out your desk. You’re not the pivot, you’re a cog—an inefficient middleman who’ll get cut faster than Jeff Bezos can burn down a bookshop.

I sympathise. Truly. Before taking up sculpture, I did my time as an animator. I wouldn’t return to that digital salt mine but I will admit that my muddy fingers sometimes twitch to press CTRL Z. This morning, for instance. I’ve been working on an equestrian sculpture. As an Irish winter surrenders to spring, a greenhouse makes a pleasant place to work, but I left my sculpture there overnight and an unseasonable frost fell. Clay needs to be kept moist and this morning I found my horsey bloated with ice, laced with hairline cracks. There is no undo in this vale of tears called Reality so I must let it defrost in the sun. Accidents like this make me worry that I’m a reactionary fool. The AI panic reminds me that it’s tough all over.

Objectors will get no further than their luddite ancestors—which doesn’t necessarily mean they are ignorant. No one could call the game developer David O’Reilly a technophobe. His objection is ethical and particularly focused on the programme DALL-E, which essentially plagiarises online art and photography. O’Reilly’s peeked under the bonnet for us. It’s a scam, he says, that harvests human creativity, ripping “off the past generation for the current one.” DALL-E’s creators are “selling tickets to take weird photos of big data,” a business model that makes them “no better than grave robbers.” Balzac’s maxim springs to mind: behind every great fortune lies a great crime.

— AndreVieira.eth (@andrevieiraart) July 28, 2022

As with all cutting-edge tech that threatens older occupations, a sense of inevitability prompts dread in some and utopianism in others. Wherever the microchips fall, this cyberpunk Götterdämmerung is like something dreamt up by William Gibson. Gibson was my gateway drug into science fiction, back in the pre-sensitivity-reader era when the genre was a place where thought experiments were fearlessly explored. Fans exaggerate SF’s predictive powers but it has a light-year sized blind spot. Fictional futures are all hell. If tomorrow seems perfect, rest assured the curtain will pull back to reveal a dystopia: where the masses are suckered (Soylent Green) or exploited (Metropolis) or oppressed by creepy theocrats (The Handmaid’s Tale). Perhaps paradise is simply boring. Perhaps we enjoy imagining our ruin because we know, deep down, that we’re safe. A storm outside makes a crackling fire warmer.

Prose and art generating apps are currently trivial diversions—Candy Crush for the intelligentsia—but their potential is momentous. They preview a world transformed, one in which we matter less. Existential crises are never pretty. Just ask Copernicus. Conceptual revolutions that undercut the much-cherished idea of human centrality are always met with wagon-circling. Darwin published The Origin of the Species in 1859. A decade later, the Pope declared himself infallible. And here we are again, staring into the abyss and getting the willies.

It’s clear now that most Ted Talks of the noughties celebrated “disruption” because the bourgeois caste who profited from the IT revolution imagined that disruption was something that happened to other people. Now, they glimpse their own obsolescence in apps like ChatGPT and Midjourney. Petitions to ban the siege engines circulate in besieged ivory towers. But it’s too late for a Butlerian Jihad.

Back when computers were a novelty, William Gibson warned that the future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed. Twenty years ago, chess aficionados went through this agony when IBM’s Deep Blue defeated Kasparov. Today, chess remains as diverting a waste of time as ever, enjoyed by more people than any time in history—and mostly online.

But it would be a gross simplification to pretend that the only ones wary about AI are those who fear for their jobs. To some the objection is more philosophical. To others theological. To the environmentalist Paul Kingsnorth, also writing in UnHerd, it’s both: “Artificial intelligence is just another way of saying Anti-Christ.” What he means, I think, is that technology increasingly impinges on our few remaining sacred spaces, like the family hearth. He’s on to something too. “The work of what we have come to call Progress,” he laments in a different UnHerd article, “is the work of homogenising the world.”

Kingsnorth is at the intellectual deep end of a modern cult of the Primitive. The troubled youth who once became Young Torys or Unabombers are now pumping iron and extolling the virtues of the Bronze Age Mindset. (I’m a sucker for this atavistic malarky myself. Much to my wife’s concern, I unwind watching six-hour YouTube videos of axe-wielding men building log cabins in Baltic forests.) We’ve all been cornered at a party by one of Uncle Ted’s nephews and told we better have our bugout bag prepped, man, because AI will do to Homo sapiens what we did to the Neanderthals.

This Black Mirror scenario may be entertaining but it’s not really plausible. As Steven Pinker and Hans Rosling have exhaustively demonstrated, we’ve never had it so good, and thanks largely to technology. All of us everywhere live better than our ancestors, by any metric you care to use. Yes, past performance is no guarantee of future earnings and, yes, we have much to worry about—overpopulation, peak oil, and Harry Styles going back into the recording studio—but should Artificial Intelligence be on the list?

Artificial or organic, I rather like intelligence. Frankly, I’d like to see more of it. Whatever trouble tomorrow brings, we need our wits about us. In the next half-century, augmentation of those wits by means of drugs, genetics, and computers will be big business. The widespread use of smart phones is a preview of the benefits and also of the unforeseen harms. Consider again navigating by phone. Unlike a compass, prolonged exposure to GPS makes you an incompetent pilot. But GPS is, on-average, more effective and easier to use, so too bad for the compass makers.

No one with a Twitter account could credibly argue that we use smartphones optimally. Everyone is hauling an encyclopaedia set around in their pockets and the result is bedlam. Life flows a little smoother for those few who are already, at some level, informed, but the mob gleefully uses it to entrench their ignorance. We know experts are subject to groupthink and overconfidence, but these tendencies can be offset by aggregate studies that reveal and screen bias and the type of crowd intelligence best tapped by technology—technology we’re mainly using now to find somewhere downtown that does good ramen.

My pet metaphor for this great untapped potential, if you’ll indulge me a moment more, is the Horseless Comanche. Throughout history, the Eurasian Steppe repeatedly threw up ferocious tribes—from the Huns to the Turks—who terrorized their neighbours through mastery of the horse. Although the American Great Plains are geographically similar to the Steppe, the modern horse only came to America with the Spanish in the 1500s. Once loose, these mustang herds changed everything. In Empire of the Summer Moon, S.C. Gwynne tells how the horseless Comanches were a nondescript tribe of hunter-gathers transformed in a single generation to mounted warriors as skilled as the Mongols. For two centuries, they lived a glorious Indian Summer, hunting, raiding, becoming legend.

My metaphor, I admit, has hard limits. Although the horse allowed the Comanche to fulfil their potential, techno-sceptics will observe that it came from the same place as the diseases that ultimately destroyed Native American culture. Perhaps that perfectly sums up the journey we are beginning: great peril but also great potential. And wherever this ride ends, we shall not recognise ourselves when we arrive.

The journey is already underway. Were a research moratorium to be imposed, it would simply surrender AI and all its promethean promise to the military, and AI is too important to be left to the generals. It’s time to put aside childish fears of novel technology and face facts. We already live in a world built by dauntless engineers and have long sped past the point where the precautionary principle might apply. The problems we have cannot be solved by retreat—even if retreat were possible. So, mount up, caballeros. Somewhat later than advertised, the 21st century is about to begin. Me? Sorry, I’m needed back in the Middle Ages. My horse has defrosted.