China

Beijing’s Campus Offensive

Chinese-supported student groups in the West are being used to control discussion about China, censor critics, and lead protests against invited speakers

In many parts of the world, China is increasing its efforts to control groups and individuals connected to civil society, politics, and universities. Its means of doing so include cultural influence; educational diplomacy; the funding of political parties; control of student organizations; swaying policy through the use of allies placed within other states’ business and governmental elites; and the operations of the United Front Work Department (UFWD), a large state intelligence organization that reports directly to the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Beijing’s use of such tactics was limited. But in the Xi Jinping era, Beijing has boosted the size and power of the UFWD, and given it far more operational latitude—particularly when it comes to overseas ethnic Chinese communities, university groups, and youth organizations. The UFWD’s operations are mostly covert, and often are manipulative in nature.

Beijing has always viewed ethnic Chinese communities in other countries as being naturally inclined to support China; and so, with it, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—though this is often far from true. UFWD-linked organizations have used their influence to sway voting intentions among ethnic Chinese voters, and even sought to insert preferred candidates into the electoral politics of such countries as New Zealand and Canada. UFWD-linked figures have played sizable roles as donors and organizers in these countries’ politics, and increasingly have brought their influence tactics into state and local politics, as the Associated Press uncovered recently in Utah.

In the field of education, China has expanded its efforts to woo foreign students, with the soft-power goal of boosting future opinion leaders’ views of China. Beijing also regularly hosts principals and other academic administrators from schools in various regions, including Southeast Asia. Once back home, these officials often prove inclined to pitch their students on the merits of attending university in China.

A study by AidData found that, at least before the pandemic, such efforts to promote study in China have had a significant effect: Over a third of surveyed international students who studied in China said they’d learned about the scholarship opportunity from a public announcement, often at school, while roughly another third said they’d heard about it from personal contacts (a group that would include school administrators).

Meanwhile, China’s government, operating through the UFWD, linked organizations, embassies, and consulates, has used student groups to advance its interests in other countries. As a study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies has shown, for instance, some student groups and ethnic Chinese community organizations in Australia are used by the UFWD to help those with sympathetic views of China’s foreign policies “rise to local prominence.” (Like Canadian universities, Australian schools tend to be highly dependent on income from foreign students, especially from China, and have seemed reluctant to investigate and crack down on student groups that could be linked to the UFWD.)

In some cases, Chinese-supported campus groups have sought to control discussion about China, censor students and professors critical of Beijing, and lead protests on campus against invited speakers with links to Tibet, Taiwan, or organizations that oppose Chinese government policies (or even posters that highlight China’s rights abuses in places such as Xinjiang and Hong Kong). The Chinese President himself declared in a 2015 speech that control of these kinds of Chinese students associations overseas should be a priority.

A study by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute found that, in Australia and elsewhere, such students associations have surveilled Chinese nationals, organized “rallies and promotional events in coordination with the Chinese government,” and pressured students not to discuss topics sensitive to Beijing. Such concerns have been raised in Canada. And a study by the Washington-based Wilson Center came to similar conclusions about Chinese government influence at US universities.

This activity has had a chilling effect: Chinese students and even non-Chinese nationals at many universities increasingly censor themselves when speaking about topics related to China; and fewer universities invite speakers who comment on certain topics. According to researcher Isaac Stone Fish, even leading academics in the United States are becoming more cautious about any open criticism of the Chinese government. As Stone Fish notes, some of these effects are obvious, as when schools such as North Carolina State University cancel visits by the Dalai Lama. But often it happens in less overt ways, with Chinese national students being harassed and bullied on social media to censor themselves.

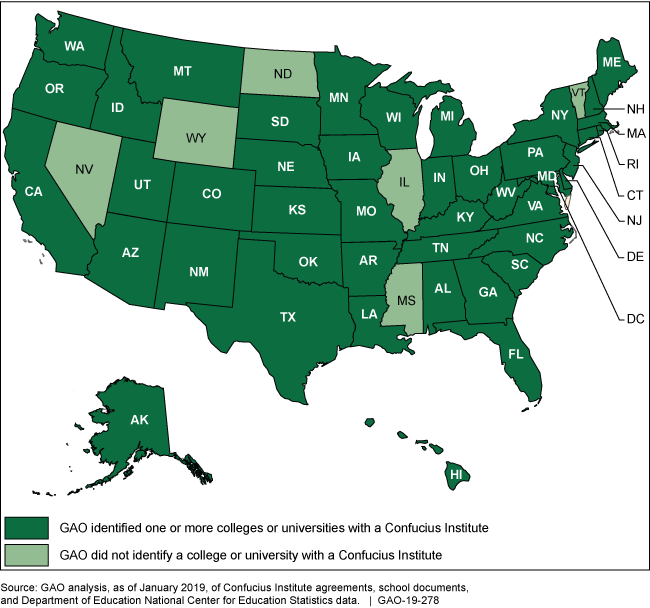

Confucius Institutes—the Chinese language and culture centers seeded by Beijing on many foreign college campuses—have sometimes contributed to silencing critical commentary about China; as has Beijing’s willingness to offer visas to foreign researchers who avoid criticism of Chinese policies, while withholding visas from the scholars who are most critical of Beijing. A US Government Accountability Office study of Confucius Institutes found that a broad range of school officials, researchers, and other staff from schools that hosted the institutes expressed concerns that their operations could be narrowing the scope of dialogue. And a Senate Homeland Security subcommittee report on the same subject offered an even more severe assessment. Its authors concluded: “Absent full transparency regarding how Confucius Institutes operate and full reciprocity for U.S. cultural outreach efforts on college campuses in China, Confucius Institutes should not continue in the United States.”

This article is adapted from the author’s newly published book, Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World.