Quillette Cetera

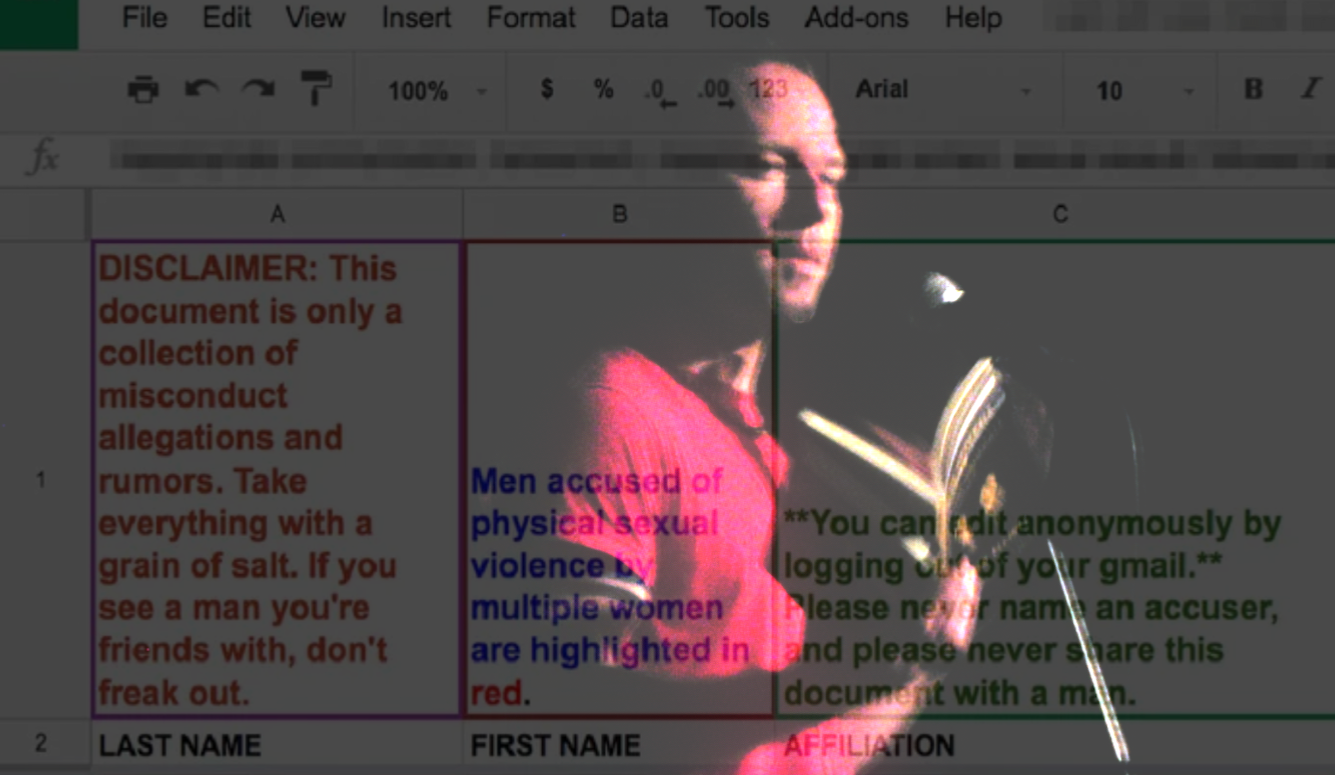

The ‘Shitty Media Men’ Legal Saga Comes to a Close

Years after being falsely accused of rape, Stephen Elliott will receive a six-figure defamation settlement from Moira Donegan.

In September 2018, Adderall Diaries author Stephen Elliott described the extended nightmare he’d endured since being falsely accused of rape on “Shitty Media Men,” the infamous Google spreadsheet created by Brooklyn writer Moira Donegan. Rape is typically a difficult crime to prove or disprove. But as Elliott noted in his widely read Quillette essay, the unusual nature of his sex life, which he’d been open about for years, made him an unlikely target for this kind of accusation:

I don’t like intercourse, I don’t like penetrating people with objects, and I don’t like receiving oral sex. My entire sexuality is wrapped up in BDSM. Cross-dressing, bondage, masochism. I’m always the bottom. I’ve been in long romantic relationships with women without ever seeing them naked. Almost every time I’ve had intercourse during the past 10 years, it has been in the context of dominance/submission, often without my consent, and usually while I’m tied up or in a straitjacket and hood. I’ve never had sex with anyone who works in media. I am not seeking to come out about my sexuality as a means of creating a diversion, as Kevin Spacey appeared to do when he was accused of sexual misconduct. I’ve always been open about my sexuality, and I have even written entire books on the topic. I’ve never raped anybody. I would even go one step further: There is no one in the world who believes that I raped them. Whoever added me to Donegan’s list, it was not someone with whom I’ve had sex.

In October 2018, shortly after Elliott’s Quillette article appeared, he filed a defamation suit against Donegan and the (still unknown) anonymous contributors who’d posted on her spreadsheet, seeking US$1.5 million and “a written retraction to each and every person to whom [the defendants] originally published the false and defamatory statements.” As first reported by the Daily Beast on March 6th, that lawsuit has now been settled, with Donegan agreeing to pay a “six-figure” sum to Elliott.

“I settled because [the suit] had already been [going on for] a very long time, and Moira settled because she knew she was going to lose if it ever actually did get to trial,” Elliott says. “If they’d stopped trying to get the case dismissed and just let it go to trial, this could have been sorted out years ago, and I would have accepted whatever the court decided.”