Politics

The Nature of the Beast

Too many Western politicians continue to delude themselves about the character of Beijing’s regime.

On Friday, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a promised 12-point plan titled “Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis.” Notably short on practical details, it called for peace talks, the maintenance of supply chains, the protection of nuclear power plants, an end to unilateral sanctions, and respect for the sovereignty of all countries. Volodymyr Zelenskyy has welcomed these “thoughts” and now wants to meet with Xi Jinping. With such a plan, the Communist Party is effectively portraying itself as the sole rational actor on the geopolitical stage, bringing order to a world of chaos (an image it has cultivated with great enjoyment ever since Donald Trump ushered in the new Age of Unpredictability).

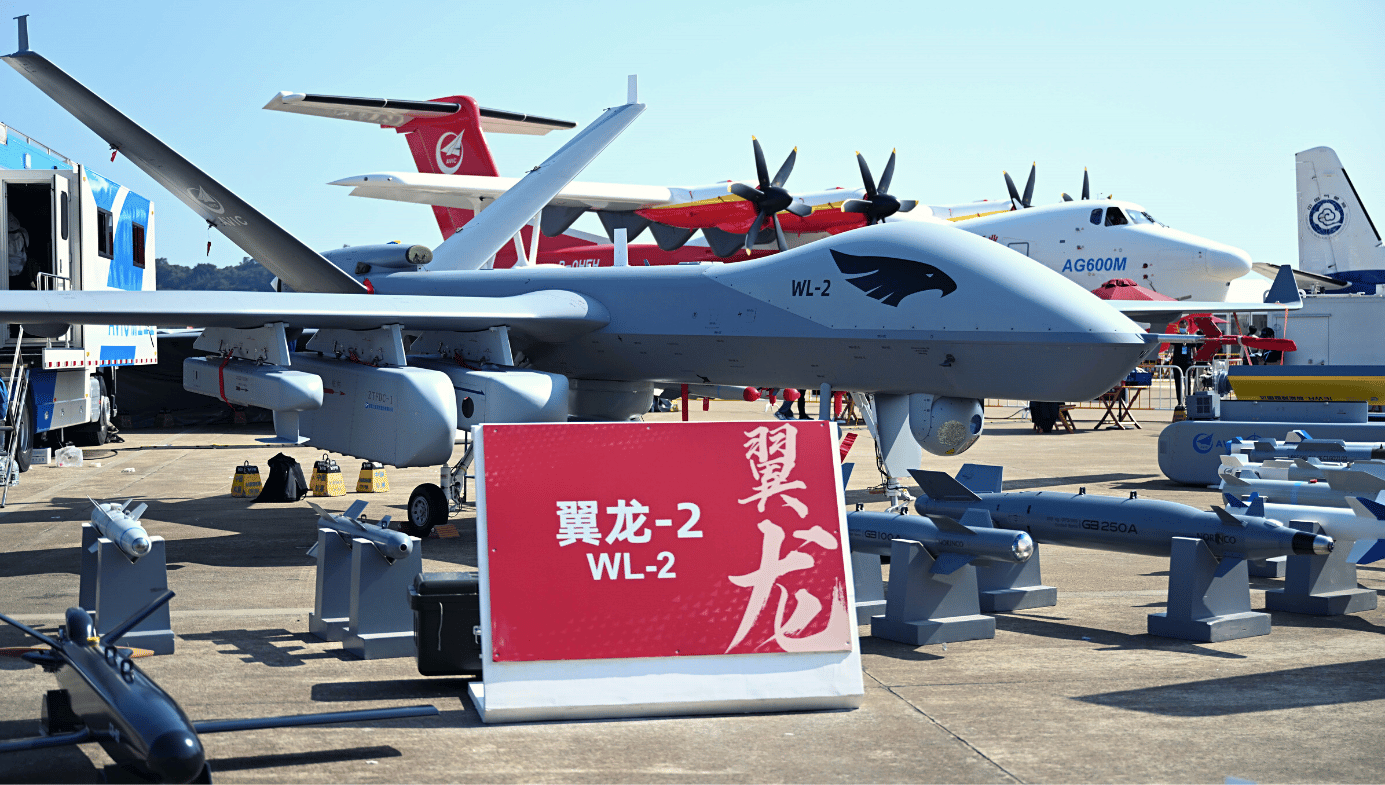

At the same time as the Party adopts this tone—grave, mature, responsible—it is preparing to send the Russian army kamikaze drones. Chinese manufacturer Xi’an Bingo Intelligent Aviation Technology is set to deliver 100 ZT-180 drones to the Russian Ministry of Defence by April, along with the components and instructions to begin further production inside Russia. Each drone is capable of carrying a 35–50 kg warhead. This follows news that a third of examined Russian missiles, helicopters, and drones have been found to contain Dutch microchips supplied to the Russian defence industry via Chinese companies. Beijing is also reported to have been providing surveillance equipment to Wagner’s brutish mercenaries.

Such behaviour is difficult to square with the 12-point plan and its solemn talk of “ceasing hostilities,” “reducing strategic risks,” and “resolving the humanitarian crisis.” Clearly, the CCP cannot be trusted. And yet we trust it still. America aside, the Western corridors of power overflow with those who take Beijing at its word. Earlier this month, Philip Hammond (the former British Chancellor to the Exchequer) spoke to the China Britain Business Council, during which he urged a return to “business as usual” between the two nations. The Uyghur genocide? Hong Kong? The horrors in Tibet? Mere “background noise.” The speech was quickly transcribed and published by Communist Party propaganda platform China Daily, masquerading as an official op-ed. It was taken down when he protested. (Hammond’s spokesman declared him to be “baffled” by this fraud—baffled, apparently, that long-proven pathological liars would indulge in a small deceit.)

Here’s Hammond’s team:

— Sam (@EditorBTB) February 17, 2023

“China Daily took the text of a speech he made to a business audience last week, changed parts of it, then claimed he’d written it for them. He didn’t.”

Via @e_casalicchio pic.twitter.com/bk1gE1tDM4

Hammond complained that his use of the term “business as usual” referred only to the return of in-person meetings after the pandemic. It was taken out of context, he said. The remainder of his original address belied this squirming self-justification. Hammond had enthused to the Council about Britain and China’s “reinvigorated relationship” under George Osborne, his predecessor as Chancellor of the Exchequer—a relationship that he was “only too happy to endorse.” He had hymned the United Kingdom’s long tradition of realpolitik (selling boots to Napoleon’s army while at war with them). “Political differences have never been and must not become an impediment to Britain’s strength,” he said. “Let us commit again, so that UK-China trade will flourish in the post-Brexit era.” Rather than a narrow comment about Zoom meetings, then, it would seem that “business as usual” had been an entirely fitting summary of Hammond’s speech and of his vision for the China-Britain relationship.

Hammond’s speech illustrates a persistent blind spot in the British and wider Western political establishment. Many people simply can’t reset: they were very comfortable with the old arrangement, the warm and cosy relationship with Beijing that was bookended by China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organisation and Trump’s 2018 trade war. Everyone made money, it worked nicely. Now the dream is over, and these people must adjust to a strange new age of spy balloons, concentration camps, vaccine nationalism, and looming war. They can’t manage it. They would rather believe in the China they were once presented with; the China that wined and dined them during the so-called golden age.

For those with eyes to see, that China was always a façade. Today it is much easier for everyone to recognise reality but Hammond and others continue to close their eyes and ears. They would never call for “business as usual” with Vladimir Putin, but Taiwan is in real danger of becoming the next Ukraine. These people overlook the similarities between the two regimes, such as the fact that Chinese executives go missing with the same regularity that Russian oligarchs are found to have suddenly tumbled out of windows or dropped dead along with their entire families.

Within 24 hours of the publication of Hammond’s comments, the billionaire founder and CEO of China Renaissance Holdings Ltd. vanished. When Bao Fan’s company reported that they were unable to contact him, China Renaissance’s Hong Kong-listed stock promptly dropped to a record low of HK$5 in early trade, wiping out HK$2.8 billion in market value. Bao had purportedly planned to move part of his fortune to Singapore—a haven for bankers seeking to escape the volatile Chinese party-state and its sudden storms. He wasn’t quick enough. Bao is not even the first executive from his company to be taken—last September, the police came for Cong Lin, chairman of China Renaissance’s subsidiary Huajing Securities. Cong has since been quietly removed from a list of executives on the China Renaissance website.

The two men join a long list. In 2008, electronics billionaire Huang Guangyu was arrested, and two years later he was given a 14-year jail term on corruption charges. In 2012, the authorities came for Xu Ming, the country’s eighth-richest man: he died in prison in 2015. At least five major executives disappeared that same year. Fosun group founder Guo Guangchang must have given the Chinese Gestapo what it wanted—he was released after just a few days (“the most special day of my life,” he said, and indeed it surely felt like a Dostoevskian stay of execution). His personal fortune was subsequently halved.

In January 2017, billionaire businessman Xiao Jianhua was snatched from his room at the Four Seasons in Hong Kong and spirited over the border by boat, so as to avoid Hong Kong’s immigration checks. After five-and-a-half long years in the care of the Chinese police, he received a 13-year prison sentence on corruption charges. Blunt-speaking property tycoon Ren “Big Cannon” Zhiqiang went missing at the beginning of the pandemic, after he called Xi a “clown.” Months later, he resurfaced in a courtroom, where he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for “graft, taking bribes, misusing public funds, and abuse of power.” And so on and so forth.

These disappearances are supposedly connected to Xi Jinping’s touted anti-corruption campaign, which has always been a smokescreen for the removal of his rivals. Xiao Jianhua, to take but one example, had links to the CCP’s Jiang Zemin faction, which opposes Xi. However, this rationale does not apply to every vanished executive. Might the real reason be ideological? China’s president has seemed at times to be channelling his inner Maoist, like a lapsed Christian guiltily and half-heartedly returning to the faith. He works the loaded term “common prosperity” into public discourse and then eliminates the nation’s richest men. But Xi’s track record shows him to be a chronic vacillator, incapable of deciding whether he wants to liberalise the economy or not. So perhaps dissent is the real issue? Some detained executives had been outspoken critics, like Jack Ma and Big Cannon Ren. And yet other detentions appear more random.

Neither corruption, pseudo-Maoism, nor the crushing of dissent can provide a fully satisfying explanation. The truth is that Xi is driven to target billionaires by his Stalinist need for total control. Just like Iosif Vissarionovich, his spiritual forebear, Xi suffers from an insatiable desire for power over human lives. To this end, he deliberately and carefully cultivates fear among his subjects by engaging in arbitrary crackdowns. Some high-profile executives vanish, are subjected to physical and/or psychological torture, and eventually handed lengthy sentences for corruption. Others are passed over.

Of course, there were no billionaire entrepreneurs in the Soviet Union. It was a Marxist system; Xi presides over a capitalist power that only pretends to be Marxist. But these governments are both species of the genus totalitarian, and Stalin’s treatment of the major Russian writers bears comparison. While all had transgressed against the Party (a great writer is anti-totalitarian by nature), their treatment varied. Bulgakov was censored and tolerated. Zamyatin was permitted to emigrate. Babel was tortured and executed. Pasternak was left untouched while his lover was sent to the Gulag (for him this was “worse than death.”) That is the nature of the regime we are dealing with. Xi’s crimes place him in the same category as the worst of 20th-century dictators, but plenty of politicians and public figures stubbornly refuse to see the truth.

The British government does have its hawks to counter the Hammond faction. Iain Duncan Smith and Lord Alton (both stalwart anti-Party voices over the years) argue that CCP representatives should be barred from Charles III’s approaching coronation. We have seen successful pushback against mooted plans to welcome the governor of Xinjiang, the man who currently presides over the ongoing Uyghur genocide and crimes against humanity. When Erkin Tuniyaz was invited to visit the UK this month for talks with the Foreign Office (and also Europe, to meet “stakeholders”), Duncan Smith and others suggested he be arrested the moment his plane touches down. Requests were put to the attorney general to consider a private prosecution. While it is unlikely that the British authorities possess the spine to go through with it, Tuniyaz was sufficiently shaken to cancel both trips.

Europe is split down the middle on China. Ursula von der Leyen may have dismissed the 12-point plan, but the EU is relaunching a “human rights dialogue” with Beijing (talks having stalled two years ago on the eve of a major investment treaty, after a Xinjiang sanctions battle). This demonstrates that Europe has learned little or nothing from its decades of dealing with the Party. There is no possibility of any serious human-rights dialogue with a pathologically deceptive and paranoid state actor that rejects the very notion of universal human rights. While the EU rolls out the red carpet, its citizens still languish in Chinese prisons, having committed no crime. Within Europe’s own borders, the CCP continues to surveil and harass members of the Chinese diaspora.

The more dovish officials cannot even see the Communist Party’s attempts to turn them against one another; the age-old tactic of “divide and conquer.” At the Munich Security Conference on February 18th, top diplomat Wang Yi simpered at EU representatives—his “dear friends”—as he encouraged anti-Washington sentiment: “Some forces might not want peace talks to materialise. They don’t care about the life and death of Ukrainians, nor the harm on Europe. They might have strategic goals larger than Ukraine itself.” While Wang pretends to care about the victims of war, Xi prepares to visit Moscow in the spring. By that time, Russia will have received its kamikaze drones. No doubt Putin will have further requests.

Dialogue is hopeless, as demonstrated in recent weeks by the saga of the spy balloon: the “high-altitude lighter-than-air vehicle” spotted loitering over an Air Force Base in Montana, and shot down off the coast of South Carolina. The airship had been detecting and collecting intelligence signals, its surveillance equipment alone the size of a regional jet.

The issue here is not espionage. We live in a world where everyone spies on everyone else, and everyone else knows they’re doing it. The problem is with the CCP’s response: its inability to defuse a crisis, to level with people, to act with the maturity it seemed to call for in that 12-point plan. On one hand, the Party has doubled down, absurdly, on its original weather balloon charade (even if this were true, China’s civil-military fusion would render it moot). On the other, it has demanded the immediate return of the debris to China, and threatened counter-measures against US entities, unable to drop for a second the hyper-defensive “Cold War mentality” that it identifies in others, and routinely wields as a favourite accusation.

The Party’s representatives are not listening to us, they don’t take us seriously, they are not telling us the truth. They consider the West to be their fundamental ideological foe. Few things could be more contemptible than the sight of Western officials clamouring to restore a friendship that never really existed in the first place.

Those who have been inside the Chinese system know the truth. In 2014, Romanian professor Marius Balo took a job with a small financial company in Beijing, providing loans to businesses. It soon turned out that someone else at the company had been failing to return evaluation and legal fees to clients whose applications had been rejected. Rather than launching an investigation, police simply arrested everyone in the company. In China, all arrests lead to convictions, despite the illusion of a functioning legal system (it is a far simpler prospect in practice: a punishment system). To live in China is to be guilty when noticed. To float within view of the judiciary is to be instantly condemned. Thus, poor Marius Balo was sentenced to eight years in prison.

Earlier this month, he looked back on his experience. He had been subjected to psychological torture and forced labour. “I witnessed a Turk die because warders denied him access to medical treatment,” Balo said. “I saw suicide attempts. I met a man whose wife and little girl had been arrested alongside him in order to extort a confession from him. No evidence was ever necessary. A simple coerced confession sufficed.”

Balo sees all this talk of a thaw in relations as illusory. He laments the sad spectacle of “our European leaders competing with each other over who goes to China first to kiss the ring.” And he is clear-eyed about the CCP. “We cannot expect such people to be ethical. There are no ethics inside that system because there are no principles and there are no principles because there is no love. They will never stop. Once they get the upper hand, there will be no limit to how evil they will allow themselves to be.”

Once we have understood the fathomless depravity of the Chinese Communist Party, as Balo now understands it, we should act accordingly. There will always be a temptation towards tribalism and dehumanisation. But each individual Party member is a complex human being who could have their eyes opened at any future point. Many important Chinese dissidents were once believers and managed to exit the cult. The real enemy is the Party itself. We might conceptualise it as a sickness, a mind virus, a manifestation of the totalitarian impulse in the human soul.

As Balo realised, we cannot let the Party get the upper hand. A show of strength is required. We need to revise the laws on human-rights due diligence, and on the market exclusion of products manufactured using forced labour, in order to make them as rigorous as humanly possible (a methodically enforced total ban on all goods from Xinjiang, for instance). Top CCP officials have assets in London, Manhattan, and Switzerland—we should seize them. For all its bravado, Beijing needs the West. Now is the time to press the advantage. And we must make Taiwan our number one focus, with a pan-Western commitment to defence of the island. The US should accelerate delivery of the long-promised and much-delayed HIMARS (High Mobility Artillery Rocket System), while all democratic states should assist with stockpiling food, munitions, fuel, and medical supplies—currently Taiwan has a woefully inadequate seven-day fuel supply. We won’t change the nature of the beast that lurks in Beijing, but with sufficient resolve we might change its behaviour.