Art and Culture

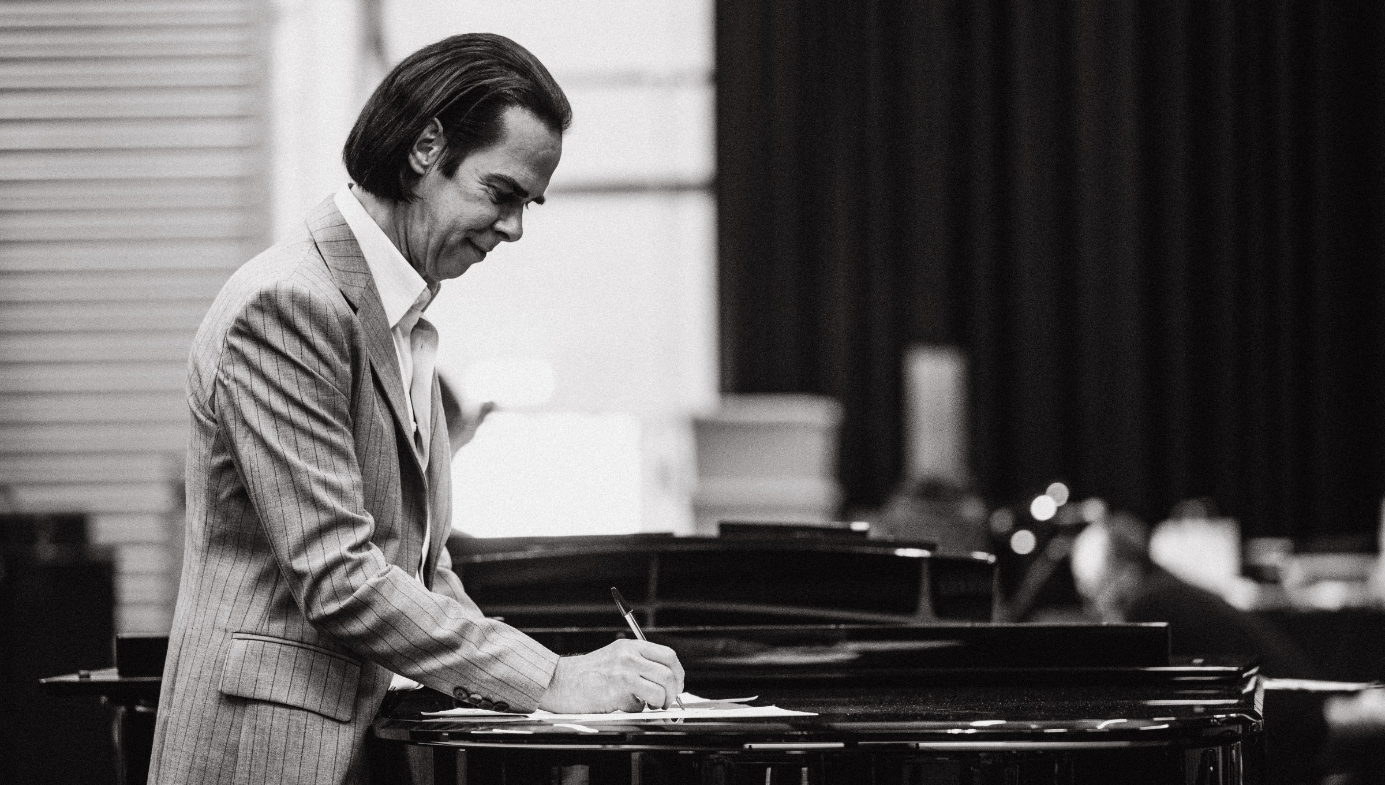

Nick Cave: “Conservatism Is an Aspiration”

The lead Bad Seed shares his thoughts on creativity, marriage, and having a conservative temperament.

In December 2022, I saw Nick Cave and Warren Ellis perform at the Sydney Opera House as part of their Australian Carnage tour. Alternating between tender melancholy and piercing defiance, Cave stalked the stage while the crowd chanted, stamped, swayed, and clapped. He reminded me of a missionary preacher committed to saving souls, including his own. When I met Cave briefly backstage after the show, I was struck by the contrast between his larger-than-life stage persona and the humility of the man in person. His ordinariness and lack of pretension are characteristically Australian.

I’ve been familiar with Cave’s music since I was a child when I was given a Bad Seeds anthology in 1998. That career retrospective was premature, however. Since then, Cave and his band have recorded a further eight studio albums (amounting to 17 in total)— including No More Shall We Part (2001), Nocturama (2003), Abattoir Blues/The Lyre of Orpheus (2004), Dig!!! Lazarus Dig!!! (2008), Push the Sky Away (2013), Skeleton Tree (2016), and Ghosteen (2019), with an 18th studio album currently in the works.

Today, Cave is perhaps best known for his elegant ballads such as Love Letter, Higgs Boson Blues, and Brompton Oratory. But his remarkably diverse musical career reaches back into London’s early ’80s post-punk movement, when his dark and discordant live performances fronting The Birthday Party would whip audiences into Dionysian frenzies.

To date, Cave has sold over five million records worldwide. In addition to his prolific output with the Bad Seeds, he has released a further two albums with another project, Grinderman; scored numerous film soundtracks in collaboration with Ellis (with whom he also recorded the 2021 album Carnage); written the screenplay for John Hillcoat’s critically acclaimed 2005 feature film, The Proposition; featured in a brace of documentaries directed by Australian filmmaker Andrew Dominik; and published several books.

In recent years, between recording, touring, writing, and sculpting figurines, Cave has somehow found time to develop a dialogue with his fans on his blog, The Red Hand Files. The site now numbers over 221 entries, including reflections on subjects as diverse as tinnitus, tattoos, free speech, inspiration, love, and more recently, ChatGPT.

In 2022, Cave released Faith, Hope and Carnage, an edited transcript of conversations with Irish journalist Seán O’Hagan, in which they discuss Cave’s unorthodox religious faith, as well as his bereavement following the accidental death of his son in 2015. Faith, Hope and Carnage has been received by popular and critical audiences with widespread acclaim.

Despite currently working on two film scores and writing the new Bad Seeds album, Cave kindly agreed to be interviewed by Quillette via email. What follows is a lightly edited reproduction of that conversation.

Claire Lehmann: The Red Hand Files is an exercise in incredible generosity not just to your fans who write in, but the wider public. You provide earnest replies to questions about bereavement, addiction, creativity, cynicism, nihilism, love, heartbreak—the full spectrum of the human experience. Have you always had this generosity of spirit—or is it something that you had to discover later in life?

Nick Cave: Well, thank you for saying that but I don’t know if generosity has much to do with it. I don’t see The Red Hand Files as a public service, as such, rather they are to do with mutuality and connectedness. It is to some degree an ongoing conversation, back and forth, with my audience and one that has benefited me enormously, changed me, pushed me toward the better end of my nature—to be less self-absorbed, more thoughtful, more compassionate, traits that do not necessarily come naturally to me. The questions in The Red Hand Files are essentially a vast repository of longing, and often extremely funny, that have helped me understand what it means to be human. What it means to be an actual person. I hope they are some benefit to those who subscribe to them.

CL: You’ve had a remarkably productive career and have contributed not just to the art of song writing, but also fiction, film, and in your spare time create ceramic figurines. Are there any limits to your creativity?