Review

The Inner Life of Transcendent Genius

In ‘The Philosophy of Modern Song,’ Dylan contemplates himself and the art form of which he is the acknowledged master.

A review of The Philosophy of Modern Song by Bob Dylan, 352 pages, Simon & Schuster (November 2022)

The last century has proved that transcendent genius is not necessarily that unusual. The science of physics, for example, produced Einstein, Fermi, Feynman, and Hawking within a few decades of each other. Cinema, meanwhile, is barely over 100 years old, and produced three authentic geniuses (Griffith, Eisenstein, and Chaplin) before it emerged from the silent era.

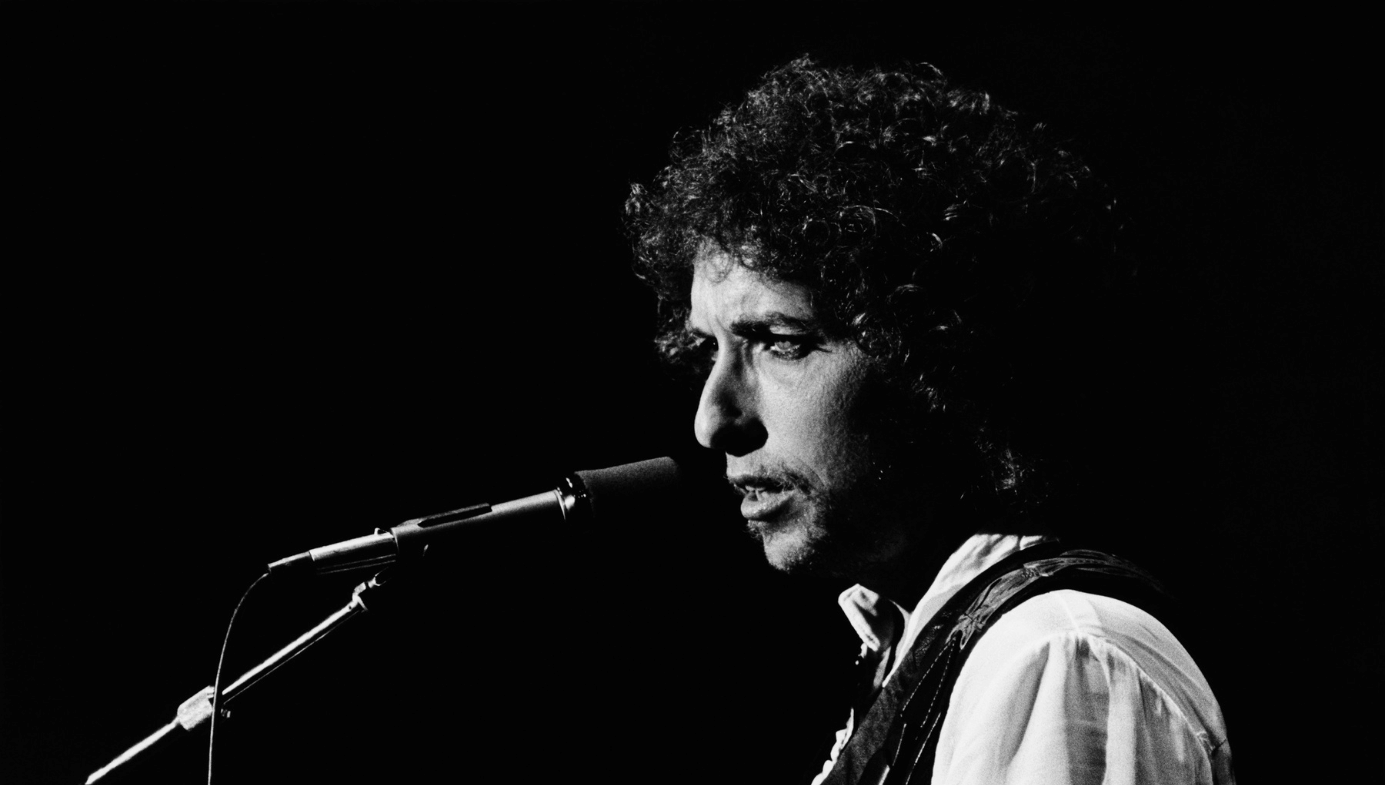

American popular music, however—if one excludes jazz—has arguably produced just one transcendent genius. Bob Dylan is now in his 82nd year, and over the course of 60 of those years, he has changed his medium as utterly and completely as Orson Welles changed cinema or Cervantes changed world literature. Dylan has effectively divided American popular music into the era before his emergence and the era that followed, in which everyone—willing or unwilling, consciously or unconsciously—trod in his footsteps.

Dylan accomplished this by liberating American pop music from itself. Pop music before Dylan was often beautiful and sometimes sublime, but it generally conformed to certain particular themes and imagery, mostly amorous, with occasional lamentations on hard times or the fervency of life lived in transient intensity. After Dylan, people could sing about anything. Forms of words that seemed at first without sense or clarity, or even comprehensibility, but nonetheless evoked something that seemed to be essential, could now reach the Top Ten.

This was not entirely to the good, of course. There were atrocities like ‘MacArthur Park’ and the wilder absurdities of psychedelia that sought but failed to capture Dylan’s cascades of imagery. But there can be no doubt that a great deal of the last six decades of pop music, including an enormous amount of extraordinary work, could not have existed without Dylan’s influence.

Beyond the question of influence, however, there is the man’s oeuvre itself. Transcendent genius is not only measured by the extent to which it transforms its chosen medium, but also by its intrinsic quality. The genius cannot only be an iconoclast, he must also be a master. In the case of Dylan, this is a difficult issue, because the oeuvre is not yet fully formed, and there is no indication that his best days are behind him.

While his early albums such as The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), Blonde on Blonde (1966), and Blood on the Tracks (1975) are Dylan’s most historically significant works, whether or not they are still his best remains an open question. After lying fallow for most of the 1980s and early 1990s, Dylan staged one of the most stunning and perhaps unexpected comebacks in American popular music. Since Time Out of Mind (1997) reestablished him as a vital force, he has turned out a series of records that constitute one of the most extraordinary runs of late works by any American artist.

Love and Theft (2001), Modern Times (2006), Together Through Life (2009), Tempest (2012), and his latest Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020) are every bit the equal of his earlier work in quality if not in significance, encompassing a long and sometimes violent meditation on the immensity of American song and its still-vertiginous possibilities. Working mostly with a stripped-down band and allowing his glorious ruin of a voice to carry the day via intricate phrasing and rhythm, Dylan’s late works walk us through the deepest recesses of the American psyche. They are emanations from the penumbra of the great unknowable McDonald’s that is life in the United States. They remind Americans, whether they wish to hear it or not, that lying below the Formica and linoleum are great tectonic powers of love and death, expressed by bluesmen and balladeers now long gone, but still there to be harnessed when the time comes—a time that seems to draw ever closer the more American music collapses into pop confection and autotuned robotics.

Dylan is not howling into the void, however. People are listening. ‘Murder Most Foul,’ the epic final track on Rough and Rowdy Ways, somehow became a massive hit despite clocking in at over 16 minutes, and the album itself became a cultural talking point. Moreover, Dylan continues to tour successfully, playing over 100 dates a year despite his advancing age. People still want to see and hear him in substantial numbers.

His legacy was also more or less cemented when he received the Nobel Prize for literature, an award that caused not inconsiderable controversy. I would contend that any man who can write “the ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face” deserves a Nobel Prize several times over. It is a line that means nothing and everything simultaneously, and while I cannot explain its precise meaning, it conjures a vivid image, perfectly suited to a David Lynch film, of both horror and intense charisma, of uncanny fascination, a distillation of love, death, and vital power—it captures perhaps, the terror of women felt by all men who are nonetheless prisoners of their desire. I am not alone in admiring its potency.

"The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face" Bob Dylan #selfie pic.twitter.com/o4qsDwQ2Zv

— Suzanne Vega (@suzyv) January 2, 2016

Those of us who approved of Dylan’s receipt of the Prize, however, are faced with the dilemma that Dylan is, at least in a sense, not a writer. He is a lyricist, a songsmith, and a performer, not a man whose words are set down on the page to be contemplated in silence as mere letters. This changed somewhat with the publication of his fascinating quasi-memoir, Chronicles Vol. I (of which it now seems safe to assume there will be no Volume II). Chronicles proved that Dylan has some talent for pure prose, but in a somewhat affected and assumed style. Yet the fact that a coherent and singular voice was present throughout was a refreshing change from the usual ghostwritten rock star autobiography. Perhaps the best part of Chronicles was Dylan’s retelling of the creation of his album Oh Mercy (1989), in which he recounts his emergence from the creative doldrums and the beginning of his artistic renaissance and return to form.

Chronicles, however, has now been matched with a new and superior book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, in which Dylan turns to the exploration of his art form, with results that, while occasionally flawed due to purplish language, are nonetheless fascinating. The Philosophy of Modern Song has, as great works usually do, a formal structure that permits the non-existence of any structure at all. Dylan picks a collection of songs, mostly lesser-known deep cuts by artists as varied as The Clash, Elvis (Presley and Costello), Frank Sinatra, and several by Johnny Cash—who Dylan, rightly, seems to revere above all—among a multitude of others. His exploration of each song usually consists of two parts; the first a free-associative, Kerouac-style contemplation of the song itself, and the second a more straightforward recounting of either the song’s creation and legacy or a tangential issue raised by both.

While there are moments of linguistic excess in the book, watching Dylan enthuse is mesmerising, as he forges non-linear, associative connections with the assurance of a Talmudic scholar. A remarkable soliloquy on Presley’s ‘Viva Las Vegas,’ normally considered one of the King’s more vapid efforts, produces “this is a song about faith. The kind of faith where you step under a shower spigot in the middle of a desert and fully believe water will come out.” This leads to a riff on faith healing in which he declares:

The interesting thing is, you talk to the guy in the wheelchair, and he believes it too. It’s powerful medicine to be onstage and have people cheering for you. Adrenaline, endorphins, and who knows what else were pumping through that person’s system and he probably actually was without pain for the first time in maybe his whole life. No matter how you explain to him what just happened, he too thinks he was part of a miracle. And that’s how faith works. And real hustles, the really good ones, have to have a little faith in them. Like W.C. Fields said: “You can’t cheat an honest man.”

Then, the ecstatic prose abruptly turns to melancholy, with Dylan noting, “Today, Elvis is gone, the Colonel is gone, Doc Pomus is gone. B.B. and Dr. John are gone. Meanwhile, Hilton now owns thirty-one hotels in Las Vegas. The house always wins.” In this single passage, we find a meditation on faith, religion, charlatanism, live performance, suffering and death, corporate capitalism, the mystical experience, and the thought that perhaps the age of miracles is not quite past. This would be a formidable achievement by any definition, but particularly so for a writer who does not usually work in prose.

At times, Dylan’s associative discourse can be disarmingly perceptive, such as in this passage about ‘I’ve Always Been Crazy’ by Waylon Jennings:

This is a song where you’re giving some hard-earned advice to the woman who’s thinking about giving her heart to you. You’re being honest, on the up and up, you don’t want her to have the wrong idea about you. In other words, you may be too good to be true, you’re being candid and want her to be certain that you’re the one for her, but you’re not sure she knows what you’re getting at.

All of which reminds the reader that, contrary to certain misandrist stereotypes, men are often quite honest with women about what they want, and just as often, women do not listen, and chaos ensues.

The more straightforward sections contain their own insights. A particularly affecting passage on Ricky Nelson recounts Nelson’s participation in an oldies revue in his middle age, alongside “Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, the Coasters, Bobby Rydell, a bunch of others”:

They were all good, did their hits. Rick was the only one out there trying to do new material. Oh, he did a couple of familiar songs. But he also did some of his newer songs. People booed. Later he wrote a song about it, called ‘Garden Party,’ and took that song into the top ten. The people who came and saw him again didn’t even recognize themselves in that song.

With great economy and clarity, Dylan conveys the essential tragedy of Ricky Nelson, a young man forced into rock ’n’ roll by unscrupulous stage parents. He found enormous success he could not enjoy, because he knew it was a manufactured thing to which his talent was irrelevant. But he succeeded in making something real from it even so, despite the opprobrium of his ancient fans. Yet Rick Nelson would always be Ricky, even if he at least had the distinction of starring in Rio Bravo, one of the greatest Westerns of all time. Cinema, thankfully, lasts forever. In Dylan’s hands, Rick Nelson becomes a tragic hero of sorts—an Orestes of the lower depths of American popular culture, and a perfect Dylan character as well, given that the master has always had a strong sense of time, transience, and tragedy. If Rick Nelson had not been real, Dylan might have invented him as a character in one of his songs.

The most striking aspect of The Philosophy of Modern Song is how autobiographical it is, and how revealing of an artist who has assiduously cultivated his own mystery for 60 years and done almost everything possible to reveal nothing about himself. In some ways, it is more like a memoir than Chronicles, as it is a memoir of Dylan’s art, which is all that he has ever been willing to reveal. Sometimes, as in his Bootleg Series, he has only revealed it years after the fact.

This is a strange, misdirected, indirect autobiography, but no less intimate for all that. “Knowing a singer’s life story doesn’t particularly help your understanding of a song,” Dylan writes. But perhaps it is possible to know a singer’s life, the inner life that is the only real life of any artist, even if one does not know the story, and one can glean it only from the artist’s stories of other people. At one point, for example, Dylan says gnomically, “in the past you entertained yourself with other people’s hearts, you stretched the rules.” This is precisely what Dylan has done throughout his career, most famously when he “stretched the rules” by “going electric” and scandalizing the entire folk music establishment before creating some of the most extraordinary rock music ever hurled into the faces of an unsuspecting audience.

Indeed, despite the oblique denial Dylan employs, there is a strong feeling throughout the book that he is writing about himself while ostensibly writing about other people. He speaks, for example, of the man who clothed many of the great country singers, as well as Elvis Presley, as “a Ukrainian Jew named Nuta Kotlyarenko who came, like so many others, to the United States one step ahead of the pogroms of czarist Russia.” This is a man not so different from Dylan’s own ancestors—Jews who fled persecution to the United States, even if to so strange a destination as quasi-Arctic Minnesota.

Dylan hints again at his own ambiguous identity when he writes:

There’s lots of reasons folks change their names. Some have new names thrust upon them as part of religious ceremonies, coming-of-age rituals or arrival into new lands where the unusual diphthongs or combinations of consonants coupled with hitherto unseen umlauts and tildes force ethnic names to be shortened into blander alternatives.

Bob Dylan was, of course, originally Robert Zimmerman and he too took a new name as part of something like an arrival in new lands and a coming-of-age ritual, his ethnic name shortened, perhaps not into a blander alternative, but at least an alternative. In this strange, associative way, Dylan also hints at his Jewish identity, which may be the deepest and most complex and fraught of any Jewish artist since Kafka. He is both a quintessential Jewish Jew and a quintessential “non-Jewish Jew,” and whenever one conquers the other—such as when he briefly converted to fundamentalist Christianity—his artistry dies, only to be resurrected when he re-embraces the paradox of his ambiguous identity.

There are other seeds of self-revelation in the book, remarkable for someone who has always shrunk from self-revelation in everything except, perhaps, his music, and even this is occult and allusive. “Marriage,” he writes, “is the only contract that can be dissolved because interest fades.” And “putting melodies to diaries doesn’t guarantee a heartfelt song,” words from a man who created Blood on the Tracks, perhaps the most intimate and devastating “divorce album” ever made.

There is also this: “Each generation seems to have the arrogance of ignorance, opting to throw out what has gone before instead of building on the past,” an approach Dylan has long rejected, with his roots struck deep into the firmament of American song. And we read, “Joni Mitchell’s ‘The Circle Game’ tells a story about a boy whose dreams are dashed at age twenty but hopes there will be brighter days ahead. It’s supposed to be optimistic but if your dreams are fulfilled at twenty, what do you do with the rest of your life?” something Dylan could have easily said about himself at the height of his early fame.

There is even a barely concealed reference to his own singing style when he refers to a singer who “jammed phrasing in all over the place, and he was doing it way back when. Try to sing the last verse of this song without jamming phrasing in all over the place.” Dylan, of course, has long rammed innumerable words together, overwhelming his rhyme scheme but overcoming it with perfect diction and timing.

Indeed, a great deal of The Philosophy of Modern Song is not just Dylan contemplating himself, but also the art form of which he is the acknowledged master. He often seems to be dropping careful hints as to how he actually does it, such as “A big part of songwriting, like all writing, is editing—distilling thought down to essentials. Novice writers often hide behind filigree”; excellent advice for writing in any medium. There is also the revelation that “sometimes songs show up in a disguise. A love song can hide all sorts of other emotions, like anger and resentment,” something that has always been the case with Dylan’s often strange and ambivalent love songs such as ‘Just Like a Woman.’

He further notes, “Songs can sound happy and contain a deep abyss of sadness, and some of the saddest sounding songs can have deep wells of joy at their heart,” which reminds me of lesser-known tracks like ‘I’ll Remember You’ and ‘Death Is Not the End,’ which despite their intense melancholy, always on the verge of tears, nonetheless contain a certain defiance and joy at the remembrance of life and love. In many ways, Dylan is an expert at conveying the essential tragedy of all song. Happy people, after all, do not write songs, and usually do not write at all, but hopeful and defiant people do. They serve and redeem tragedy through ambivalence. Even Aeschylus, after all, eventually gave Orestes a happy ending.

In the end, Dylan describes music as something almost ecstatic, summing up the essence of his art as a movement of time and space, asserting that music

is of a time but also timeless; a thing with which to make memories and the memory itself. Though we seldom consider it, music is built in time as surely as a sculptor or welder works in physical space. Music transcends time by living within it, just as reincarnation allows us to transcend life by living it again and again.

This, in many ways, sums up Dylan’s view of music in general, and of his own music in particular. He has often said that his ambition is to write songs in which time stands still, and all things past and present can be seen simultaneously in a mosaic of the fourth dimension—all things frozen in a single moment. All of this comes from a writer who has reincarnated himself innumerable times. He has been a folk singer, a rock singer, a blues singer, a country singer, a gutter-voiced crooner, and finally, perhaps, simply himself, as we know him today, with his late works emerging from his final confrontation with the lengthening shadows before him.

A cliché holds that writing about music is like dancing about architecture. This has never been true, but The Philosophy of Modern Song disproves it more conclusively than most. In this book, Dylan demonstrates that one can evoke music via careful allusion, allowing it to spin you off in directions you would never have taken without it, allowing it to give birth to prose as powerful as sound.

Such writing may not convey the immediate experience of music, but it can be great writing if it allows music to be Epicurus’s swerve—an atom flung into the void to find itself in some new configuration; in something else unique and unknowable. Bob Dylan has always been, and will likely remain after he passes into the world to come, unique and unknowable, but in this book he allows us to know him slightly. In his allusive way, he evokes himself, and we may regard this as a great gift. As one of America’s greatest artists, he unquestionably has something to tell us.