Politics

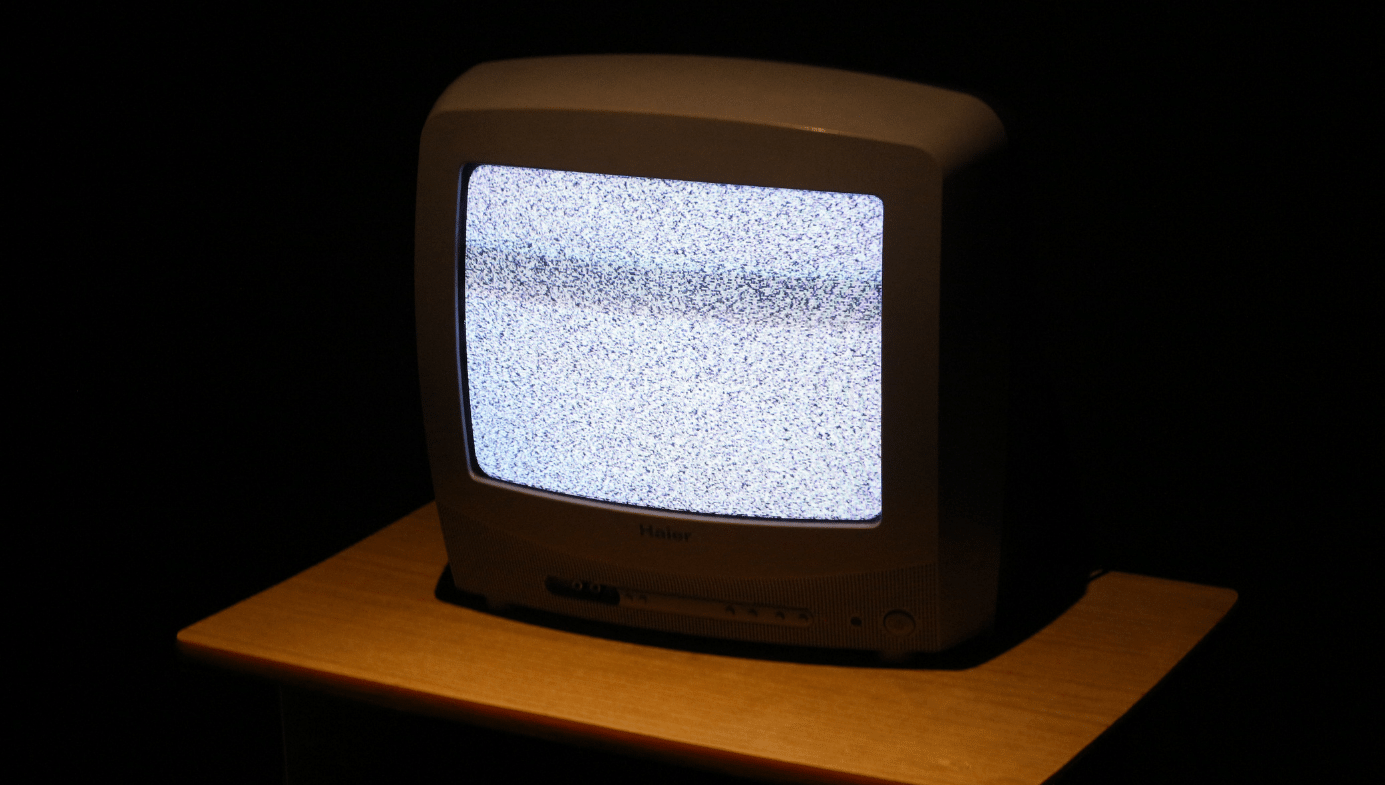

Cacophonocracy

This is what happens when the possibility of consensus among the governed deteriorates to unmanageable extremes.

Something significant and damaging has happened to our understanding of news, current events, and public affairs in the last few decades. To illustrate, here is a sampling of headlines from the New York Times on October 18th, 1985:

- Skin Cancer Was the Second Excised From Reagan’s Nose

- Money Fund Assets Fall

- Sandinista Target is Enemy At Home

From 1976, this selection of articles was published in the June issue of the Atlantic:

- Delusions of Power: The Great Debate Over Nuclear Energy

- The Plains Truth: An Inquiry Into the Shaping of Jimmy Carter

- The Heifetz Collection [classical music record review]

And in Canada, the country’s leading newspaper, the Globe and Mail, put these stories on its front page on October 19th, 1973:

- Saudis Cut Oil Production

- PQ Accused of Eliminating Non-French Voters

- Biggest Tank Battle is Fought Along Suez

- Nixon Supporter’s Bank Declared Insolvent in US

Now, jump to the present. This is what the New York Times deemed newsworthy on October 19th, 2022:

- Ye Is Running Out of Platforms

- Fox News CEO’s Strategy at Center of $1.6 Billion Lawsuit

- Preserving a Palestinian Identity in the Kitchen

And although the Atlantic still publishes a print edition, these were some of the pieces posted on its home page the same evening:

- Everyone Wants to Be a Hot, Anxious Girl on Twitter

- The End of a Millennial Internet Era

- What My Mother Taught Me About Black Conservatives

- TV’s Last Truly Unbothered Show

Meanwhile, the Globe and Mail’s online feed that day highlighted the following topics:

- World of Barbie Shines a Pink Spotlight on the Original Influencer

- I Went to Tahiti to Get a Tattoo. I Got a Lesson in Resilience

- Why ‘Bringing Your Whole Self to Work’ Can Be Risky for Black Professionals

We can see from these examples that, over the passage of one reader’s lifetime, the criteria for what constitutes information important enough to merit space in serious and long-established outlets (the New York Times first ran in 1851, the Atlantic in 1857, and the Toronto Globe began in 1844) has changed significantly. Of course, there was always a yellow press and tawdry scandal rags; and to be fair, the Times, the Atlantic, and the Globe still employ traditional correspondents who chronicle elections, disasters, and foreign conflicts. What’s different today, however, is how deeply triviality—for that is what it is—has integrated with substance within single forums and on single screens.

In the past, print or broadcast journalists would devote little time to Hollywood or Broadway, to hit sitcoms or underground musicians. Entertainers were widely publicized in fan magazines, trade papers, or gossip columns, certainly, but there was a strong distinction between hard news and soft, between the International and the Lifestyle sections, between scrupulously researched business or crime reporting and the simple reiteration of a promoter’s press release. A senate race and an Oscar race might not be covered in the same publication, let alone on the same page. Likewise, editorial opinions on contentious developments were firmly walled off from on-the-spot dispatches about them. But by now, those barriers have collapsed from two sides: from the production of news as a ceaseless stream of fresh content, delivered around the clock by attractive anchors or through social media; and from the dominance of news by stories from the cultural industries, with constant features on summer blockbusters, celebrity brouhahas, and endless analyses of the “meaning” of a popular song or Netflix series. The collapse may be shaking our society, our civics, and our individual psyches.

This morphing of news into entertainment has been perceived for many years. Books such as Daniel Boorstin’s The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1962), Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse In the Age of Show Business (1985), and Neal Gabler’s Life the Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality (1998) all raised alarms about the degradation of democracy and even of our essential humanity under a barrage of hype and artificial stimulation—what Boorstin named “the Graphic Revolution,” with the advent of the telegraph, photography, cinema, and broadcasting. Yet that revolution has since spawned further ones, driven by three broad influences.

First, and for better or worse, the size of the information or communications economy makes it a legitimate concern for everybody. In the same way that the fortunes of General Motors or US Steel warranted front-page attention in 1950, so now the colossi of Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Apple have justifiable claims to public import in 2022. This is the age of the staple luxury. The ominous military-industrial complex Dwight Eisenhower discerned in 1961 has been supplanted by an entertainment-industrial complex, a force so pervasive and a lobby so powerful that it can’t be ignored as mere frivolity, even though frivolity is much of what it provides. This is why the weekend box-office grosses of Marvel movies now make headlines alongside news about pandemics or mass shootings. We are, in effect, held hostage by a global arcade game, forced to keep plunking in our quarters by the gazillion or risk toppling the financial pillar on which we’re perched. What were once distractions or indulgences have become vital to national security and social stability.

Second, so much human activity has already migrated from the physical to the virtual that news has naturally followed the trail. There was a telegenic US president in 1960, an actor president in 1980, and a reality-TV president in 2016, not to mention an action-star governor of California from 2003 to 2011, a media magnate prime minister of Italy during the 1990s and early 2000s, and a comedian president of the Ukraine today; the responsibility of their offices means that the officeholders have to be taken seriously, whatever their unconventional or deficient qualifications for the job. Inflammatory tweets, Facebook posts, or leaked videos are all news today; they had no real equivalents 50 years ago. Politics is no longer only practiced in union meetings, or town halls, or voting booths, but in the casting of superhero films, in choosing the mascots of professional sports teams, and in boycotting the latest output of a disgraced performer. And whereas we once sought integration in our schools or our neighborhoods, we now celebrate diversity at our awards shows and in our swimsuit editions. Unlike assassinations or airline accidents, these stories come with their own publicity. Publicity, in essence, is what the stories are. The problem here is that the principles of justice, accountable government, and democratic representation which news is supposed to uphold have become measured by technologies and symbols that did not exist when the principles were originally conceived.

As much as anything, the explosion of content and our shriveled ability to focus in a mediated world has for several generations been affecting the mental processes of linear thought and self-reflection on which citizenship and learning are founded. The Graphic Revolution Daniel Boorstin described in 1962 was a mere intimation of what David Shenk called Data Smog in his 1997 book of that title, and which, 25 years later, is again but a fraction of all the printed and electronic information available to us. Newspapers and news magazines—indeed, the very premise of “news” itself—evolved at an early stage of this history. They were designed to collect and curate relevant facts at most twice a day, or once per week or per month. Now they must work at the speed, and the indiscriminateness, of everything else.

Their first competitors were radio and newsreels, then television, then the 24-hour crawl of CNN (launched in 1980) and its imitators, and eventually the Internet. Over this period, as well, the invention of home video players allowed viewers to play and replay favorite material at their convenience rather than wait for it to be shown by theatres or TV networks, affording them an initial expectation that they could be connoisseurs of information and not just consumers of it. Then there were television programs like the widely syndicated Entertainment Tonight, about movies and TV shows but formatted as exclusive updates and breaking stories, and often scheduled seamlessly after the actual 6pm news. “Both the form and the content of news become entertainment,” Neil Postman observed.

Alongside these were the appearance of People, Vanity Fair, and Entertainment Weekly magazines, blending movie and music reviews, celebrity profiles, and straight-up promotion in glossy Time- or Newsweek-like packages. Talk radio and panel television capitalized on the emotional appeal of anger and argument rather than the practical value of impartial intelligence. Newspapers began to run regular “Culture Desk,” “Everyone’s Talking About,” or “What’s Hot” sidebars, bylined by “media savvy” young writers not quite qualified for assignments in legislatures or war zones; activist Naomi Klein got an early break penning think-pieces about irony and hipness in the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail in the 1990s. And the OJ Simpson trial and the sex scandals of the Bill Clinton presidency pushed the mainstream news to adopt the prurience of supermarket papers. “Once television … began airing tabloid stories that had little traditional claim to importance but that could attract more viewers,” wrote Neal Gabler, “the respectable press was no longer bound by its old obligations.”

While this general drift had begun before anyone had heard of Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg, it was amplified and accelerated when society went online. The nature of the Internet is its reciprocity between distributor and viewer, so that anything published can be instantly republished, refuted, or at least responded to by whoever sees it. News organizations, which used to have a monopoly on the public record, have thereby ceded the last word to their audiences. At first, the prospect of “citizen journalists” was touted as a liberation from the censorious gatekeepers of the Establishment, but in practice the web analytics of any single outlet let established producers steer their own product towards select subsets of the same passive recipients. Far from giving free access to anyone who wants to contribute, today the gatekeeping simply runs two ways. Many sites offer customized feeds to individual users based on preferences determined by metrics—not only social media sites, where the customization is the point, but also supposedly definitive sources with “Trending” or “In Case You Missed It” sections that defer to the clicks of readers rather than the wisdom of editors. Again, there was always a drive to boost circulation figures with Page Three Girls and exclusive paparazzi shots; it’s just that the boosting is now done by algorithm, second by second instead of issue after issue.

Much of what comes to us as news is just basically information about other information: not the proverbial five-W descriptions of “Man Bites Dog,” but “Government’s Dog-Bite Numbers Don’t Add Up, Says Our Expert”; or “One-Third of All Men Would Bite Dogs: Poll”; or “Dog-Biting By Men: Last Year’s Thing?”; or “Top Ten Reasons Everything You’ve Heard About the Dog-Biting-Men Narrative Is Wrong.” A lot of this falls under the category of so-called pearl-clutching, where opposing camps opportunistically profess shock and dismay over some petty affront committed by their adversaries. In other instances, though, it’s the news that does the pearl-clutching on the news readers’ behalf, digging up mites of indignation in order to keep us upset and logged on. Unlike Marshall McLuhan’s global village, the effect is of being in a global school yard or hair salon where a gaggle of bored troublemakers whisper dirt all day—Did you hear what she had the unmitigated gall to say to him? Can you believe what they said about it? Don’t listen to those big mouths, let me give you the real scoop! Wait till I tell you, you’ll simply die when you find out! “Demanding more than the world can give us,” Daniel Boorstin summed up in 1962, “we require that something be fabricated in order to make up for the world’s deficiency.”

Across 50 or 60 years, then, the recurring implication has been that advertising, style, show business, and raw sensation are not just commercial ephemera but as meaningful as new laws or scientific discoveries, and can be reported as such. The hard line between incoming bulletin and puff-piece has evaporated. Combine that with legacy media’s increasingly desperate rearguard defense of its own mission (“Democracy Dies In Darkness,” vows the Washington Post’s webpage slogan, over headlines like “On TikTok, Instant Fame Often Comes with a Price” and “9 Highly Anticipated Book Adaptations Are Coming to Big and Small Screens”) and the result has been termed the epistemic crisis, or a regime I’d label cacophonocracy: rule by discord.

Cacophonocracy is not a system of government, obviously, but it’s what happens when the possibility of broad consensus among the governed deteriorates to unmanageable extremes. Cacophonocracy is the sheer volume of I-know-you-are-but-what-am-I exchanges that have displaced the imperfect but orderly dialogues between people and their institutions we knew in generations past. It’s manifest in the ongoing political clashes around objectivity and neutral authority, whereby what’s persuasive rhetoric to you may be dangerous disinformation to me, and one person’s fair and balanced is another’s partisan propaganda. It’s manifest in the prominence of advocacy or commentary over beat journalism, with multiple daily deconstructions of what pundit X said on talk show Y about candidate Z’s Instagram post. It’s manifest in continued battles over free expression versus hate speech, over removing Maus and Dr. Seuss from school classrooms, in pronoun wars and the n-word and canceling and reckoning and truth and reconciliation and lived experience. But it’s also there in the way even stentorian voices such as the Globe and Mail, the Atlantic, and the New York Times, which once seemed well above the fray of the diversion and disruption otherwise deafening us, have gradually been diminished into only further shouts amid the clamor—in the way they’ve joined the mob and caved in to running articles about how Barbie is the original influencer, about how everyone wants to be a hot, anxious girl on Twitter, and about how Ye is running out of platforms.