In his canonical 1993 book The Invisible Dragon, art critic Dave Hickey prophesied that the “therapeutic institutions”—art schools, museums, and fund-granting bodies—will eventually jettison any art that does not fit the bureaucratic precepts du jour. Over the next three decades, as the art world’s priorities shifted from aesthetics to ostentatious displays of political virtue, Hickey’s prediction that puritanical intellectuals and activists would conquer culture in the name of social justice has been conclusively vindicated.

The conquest was slow but steady, and it included occasional victories for aesthetics, but in the end the culture warriors prevailed. In the summer of 2020, several high-profile police killings of African Americans led to a swell of protest, prompting museums, art schools, and magazines to advertize their anti-racist bona fides by posting stock statements on their websites, adopting a black square profile icon, and sharing politically correct hashtags on social media. Those who did not comply in a timely manner were mobbed on Twitter. Those who had the audacity (or the ignorance) to use the wrong hashtag were shamed and fired. By the end of 2020, the alignment between approved politics and professional access was complete.

Perhaps the most notorious instance of collateral damage caused by “therapeutic institutions” acting as self-appointed guardians of justice and virtue was the case of Philip Guston. In a bid to pre-empt any negative impact that might be triggered by his allegedly offensive portrayals of hooded Ku Klux Klan figures, museum administrators indefinitely postponed the long-awaited, multi-venue retrospective “Philip Guston Now” scheduled to open at Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art in late 2020. One of the show’s curators, who dared to criticize the decision, was effectively hounded out of his job at London’s Tate Modern. “If you work at Tate, you are expected to toe the party line,” explained a source who, understandably, asked to remain anonymous. “There is very little tolerance for dissent and an increasingly autocratic managerial style.”

Although the exhibition’s catalogue contained plentiful proof of Guston’s commitment to anti-racism, the administrators argued that it was the potential impact on the viewer, rather than the intention of the artist, that mattered. This particular story had a happy ending: due to determined pushback from artists, critics, and curators, the decision was reversed, and the show is now passing through the venues as planned. Nevertheless, the precedent was set—before arriving at aesthetic considerations, an artist will have to pass a litmus test of “impact.” Any artwork, no matter how aesthetically accomplished or historically significant, will be inadmissible unless it is cleared for the audience’s political comfort.

This new status quo is hardly ever challenged, so the recent case of a California artist successfully standing up to curatorial orthodoxy deserves notice. Born in San Bernardino in 1938, Ben Sakoguchi has been a fixture of the SoCal art scene since his student days at UCLA in the early ’60s. Sakoguchi is a career artist. His work has been shown in public and private venues, he has received half-a-dozen fellowships ranging from local to national, and he has been a professor of Art at Pasadena City College for over 30 years. Yet Sakoguchi is hardly a relic. He remains highly active, working and exhibiting in commercial galleries in both LA and NYC.

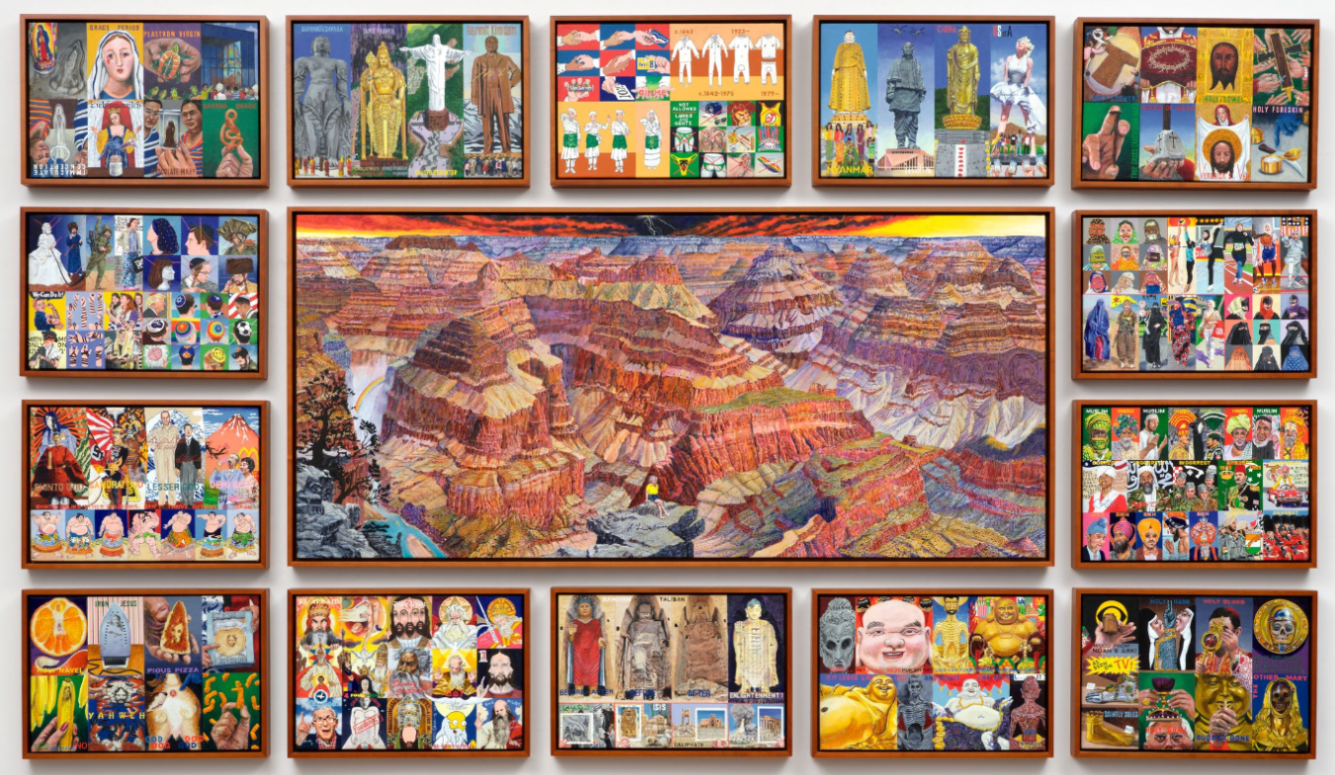

In January 2022, he was among 20 artists invited to participate in the California Biennial, to be held at the Orange County Museum of Art, which was reopening with great fanfare in a brand new $94 million Morphosis-designed building. According to the museum website, the exhibition, entitled Pacific Gold, “reflects on California and its unique place in the popular American imagination … [r]evisiting mythical stories and reimagining California as a changing land.” (There is also an obligatory reference to “distinctive voices” that “question” and “challenge.”) By June, the curators had selected a Sakoguchi work for inclusion: a 16-panel polyptych titled Comparative Religions 101. So far, so good.

But with all the paperwork completed and the artwork ready to ship, Sakoguchi was informed that OCMA’s Education Department had “raised questions about the content of his submission.” The painting contained images of swastikas. Sakoguchi was handed a list of 17 questions the museum wanted him to answer. He was also asked to provide a series of teaching-aid videos. In the following weeks, Sakoguchi set aside his studio work to answer the questions and record the videos.

Three days after submitting his written responses, Sakoguchi was informed that Comparative Religions 101 would not be included in the show “because the museum will not show any work that depicts a swastika.” It is safe to assume that the painter, who was still mired in the laborious process of recording and editing teaching-aid videos to meet the museum’s request, felt betrayed. He had taken precious time out from painting to answer the questions, record the videos, and put together explanatory slideshows, only to have his sincere and thoughtful responses dismissed with a generically flippant rejection.

Among the 20 artist invited to participate in the California Biennial, artist Ben Sakoguchi was absent, as the institution refused to display his painting Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019) on the grounds that it contains representations of a swastika: https://t.co/dCbHgZyaky pic.twitter.com/zZBz6fEKe4

— ArtAsiaPacific (@artasiapacific) October 18, 2022

Having accused an 85-year-old survivor of a Japanese internment camp of hate speech, the curators’ ensuing scramble to save face was tragicomic. Matt Stromberg’s comprehensive account of the exchanges between the Biennial curators, museum staff, the artist’s studio and his dealers reconstructs the drama that played out between the September 12th rejection and the opening of the Biennial two weeks later. Stromberg recounts the predictable shifting of blame between museum administrators and exhibition curators, the bid to secure a different work by Sakoguchi (declined), the attempts to go behind his back to obtain work from his dealers (unsuccessful), and finally a groveling email imploring the artist to re-enter the offending painting into the exhibition (denied):

Your work needs to assert its rightful place within the biennial as a reminder that communities of color are the social and economic backbone of this country and of California, in particular. Your participation in the biennial is a radical act of cultural resistance and we need your artistic voice to state loudly and clearly that we will not cower to right wing political agendas that are attempting to culturally whitewash our histories and our truths.

Sakoguchi, however, was unmoved by this flattery and remained steadfast in his refusal to have anything to do with the Biennial. Instead, he opted for a policy of glasnost, posting the entire timeline of the events, together with the 17 questions and his responses on his website. The curatorial bureaucrats were hoist by their own petard.

The reasons for this spectacular embarrassment become apparent in Sakoguchi’s written responses. Ignoring Henri Bergson’s identification of humor’s social function—that its purpose is to correct pompous rigidity, thus serving as an evolutionary safety valve—the curators opted for a literal interpretation of Sakoguchi’s work:

OCMA: Some of the visual elements and language in your work can be read as provocative and even inflammatory for the general public. How might you advise the museum to address an audience member who is uncomfortable, upset, triggered, or angry as a reaction to some of the language and/or imagery in the work?

Sakoguchi: I have no advice for the museum in that regard. I’ve never believed my role as an artist was to make work that ensured comfort. My paintings are purposefully subject to alternate interpretations, and a reading of Comparative Religions 101 that provokes anger is certainly possible if the viewer is a literalist. But I can’t explain the humor and irony in the work to a literalist, any more than I can explain Red to a person who is (red/green) colorblind.

Irony, as Sakoguchi knows, is the enemy of literalism. His approach, evidenced by the questionnaire, is nuanced and open-minded. It is the inverse of the ideological dogmatism embraced by the “therapeutic institution.” Asked what he wants audiences to learn from his work, the painter expresses hope that they will be “motivated to think and to question.” In Sakoguchi’s view, “it is okay for the viewer to be left wondering about the original source material.” Driving the point home, he ends the questionnaire by stating that he “ha[s] no answers, just questions.” The goal of Comparative Religions 101 is that “audiences will recognize some of the questions … and will posit their own as well.”

Sakoguchi uses irony, satire, and humor in general to prompt his viewers to question the rules, and to escape literalistic torpor, in search of deeper meaning. His treatment of world religions is humorous and irreverent; it does not involve the wholesale condemnation of the kind popularized by Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. He does not pretend to know all the answers. Rather, his use of humor as a discursive tool evokes the theoretical position of the Scottish psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist.

McGilchrist started out as a literary scholar at Oxford before training in psychiatry and becoming interested in neuroscience. In 2009, he published The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, which set out a hypothesis of epistemological and metaphysical differences in the ways the left and the right hemispheres of the brain may operate. He argued that, while the left hemisphere may privilege certainty, categorization, literalism, humorlessness, and fixed rules, the right hemisphere may tend towards openness to possibilities, contextualization, use of metaphor, irony, humor, and flexibility. The hallmark of the left hemisphere modality, according to McGilchrist's hypothesis, is rigid, rules-based, black-and-white thinking, whereas the right hemisphere is adaptable in its approach, and ready to change theoretical paradigm in response to changes in reality.

McGilchrist expands his hypothesis into an analysis of our current political and sociological predicament in his most recent book, The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World, published in 2021. He draws a dismal picture of what he sees as the left hemisphere’s modality gaining cultural power:

We sit in judgment on other times and other places, the art, literature and history of the past, and other people’s cultures; yet we have no idea how very weird our own values are when set in context. … There is a growth of machine-like inflexibility, loss of judgement and discretion, and a culture of petty rules that strangle initiative and affront our humanity. We are witnessing the triumph of black and white judgements, especially in the “culture wars,” where there is no vestige of subtlety in our thinking, no patience for the complex, and often little or no empathy, but rather anger and self-righteousness. We are newly beset by a tyranny of literal-mindedness—affecting our capacity to understand metaphors, humor, and irony, which increasingly are being driven out of public converse and out of our lives.

Since, according to his hypothesis, the arts are right hemisphere-dependent, McGilchrist reminds us that poetry, music, and humor are abjured “once fundamentalism rules.” He writes that “humor is dying along with wisdom: the left hemisphere Puritans are seeing to that.” “Puritanism,” McGilchrist concludes, “always was the enemy of both; and it has historically often been associated with aggression, destruction and a ferocious need to control—with power, in other words, above all else.” OCMA’s declaratory rejection of Sakoguchi’s work—“the museum will not show any work that depicts a swastika”—is a fine example of this ferocious need to control.

Sakoguchi resists not only dogmatism, but also binary thinking as such. Responding to a question about his use of “Correct”/“Incorrect” labels in Comparative Religions 101, the painter cited his traumatic childhood incarceration because of his ethnicity, which led him to reject all black-and-white thinking and embrace nuance. Sakoguchi’s account of his family’s internment, as well as the xenophobic and racist abuse he received throughout his adult life, recalls McGilchrist’s assertion that “wisdom and humor are both expressions arising from the shared suffering … both important elements in turning us away from aggression and towards healing.” The California Biennial debacle was a face-off between pedants and poets, and this time the poet won.

Correction: An earlier version of this article described McGilchrist's writing on left/right brain hemispheres as a theory, rather than hypothesis. Quillette regrets the error.