Politics

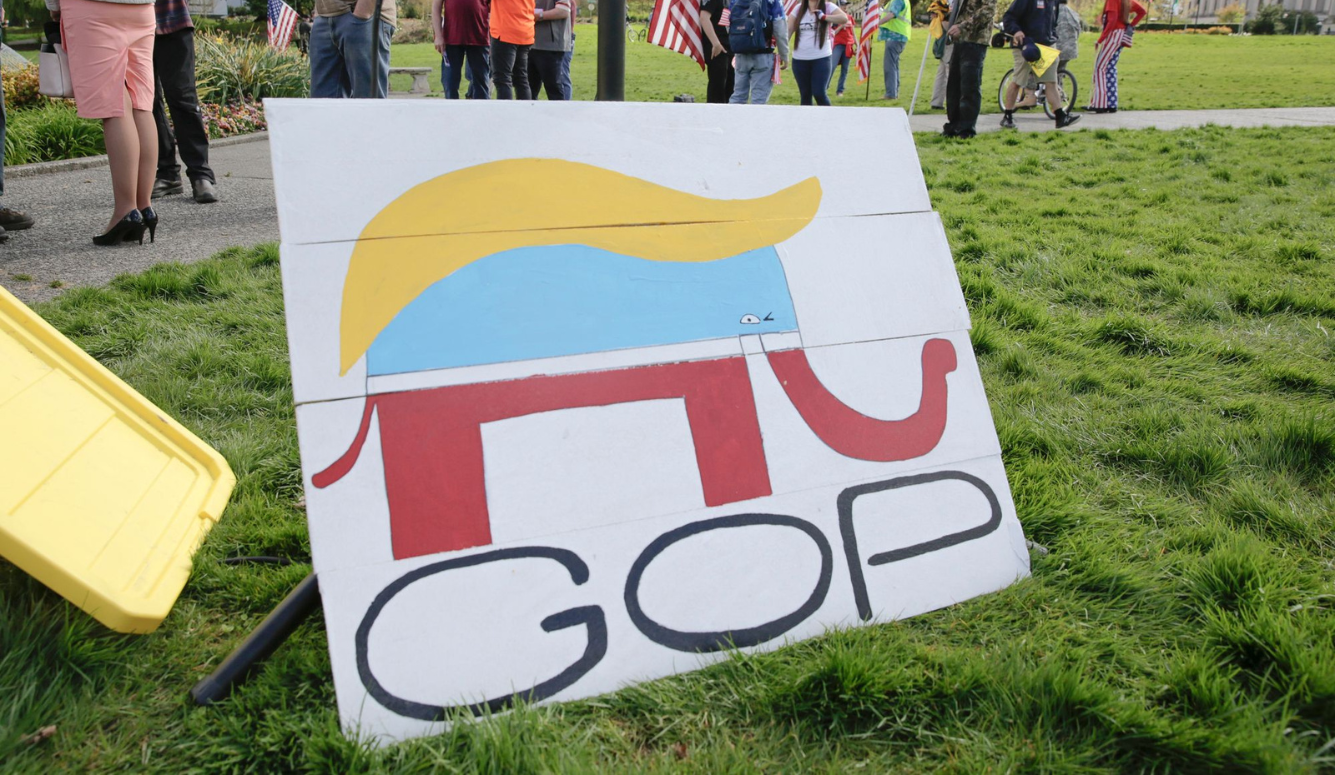

Should the GOP Continue to Embrace Populism?—A Roundtable

Editor's note: With another presidential run by Trump in the offing, we asked two writers to reflect on the costs and benefits of populism. If you would like to contribute to this discussion, please send a response of ~800 words to [email protected].

I. For a prudent populism

Dennis Saffran is an appellate attorney, political and policy writer, and a former Republican activist based in Queens, New York. You can follow him on Twitter @dennisjsaffran.

I was a conservative populist before Donald Trump came down the escalator. So, while I wasn’t an enthusiastic Trump supporter, I was a charter member of the “anti-anti-Trump” camp, seeing him as an unlikely “champion of populist revolt” who was “galvanizing the party’s voice against the trendy tyranny of ‘political correctness’ while moderating its harsh tone on economics.”

Reading that last sentence, I realize that this would be a good time to stop and define what I mean by “populism.” Definitions tend to oversimplify, but the most historically valid and politically useful one here is that employed by the Voter Study Group and other political scientists: the populist position leans left on economics but it is also socially and culturally conservative. Or, as I’ve phrased it elsewhere, populism “blends traditional social conservatism with old-fashioned New Deal liberalism—rejecting both the racial and sexual obsessions of the modern culturally liberal establishment and the growing economic inequality under that same establishment.”

An important caveat, though, is that the current iteration of populist social conservatism tends towards the “barstool” sort, focused more on issues like crime and immigration and less on religion and on sexual issues such as abortion and gay marriage. However, resistance to the Left’s efforts to mainstream transgenderism, especially among children and adolescents, links populist and religious conservatism.

Unsurprisingly, a far more malign definition of populism came to dominate academia and other elite institutions during the Trump era as blue-collar, non-college voters responded enthusiastically to the President’s (often unimplemented) populist rhetoric. As Professor Colin Dueck noted in 2019, “a small cottage industry” arose to denounce populism and populists as inherently “authoritarian,” conspiracist, insular and, indeed, “fascistic.” Prior to the 2020 election, I dismissed this indictment of populism, repelled by the intellectual snobbery that typically accompanied it.

Over the last 20 months, however, as I’ve watched much of the Trumpian base go down rabbit holes of election denial, vaccine paranoia, and Putin apologia in fits of blind rage, I’ve become much more alert to the potential dangers of populism. And yet, I would still answer “yes” to the question of whether the Republican Party should continue to embrace it.

First, one can’t ignore the contribution that years of intellectual snobbery—the contempt, and often class-based bigotry, of liberals and some NeverTrumpers who dismissed millions of working people as “deplorables” and said their communities “deserve to die”—has made to populist lunacy. I’m reminded of the famous Mike Wallace documentary on the Black Muslims in the late 1950s titled “The Hate that Hate Produced” as I’ve watched the meltdown on the Right over the last year and a half.

Second, if the populist Right has gone insane since November 2020, that insanity came on the heels of the Left, and the dominant institutions it controls, also going insane. The Left’s insanity has grown incrementally over 55 years since the 1960s, and then suddenly since the onset of the pandemic in March 2020 and the death of George Floyd two months later. The latter insanity has been marked by the blatant politicization of science and other elite institutions in the service of progressive social ideology, epitomized two years ago when “experts” who’d been telling people to stay at home in fear of COVID performed an abrupt 180 and told them to take to the streets to protest the “public health risks” of racism.

This ideologization of science has continued apace—to take just one example, the Association of American Medical Colleges recently released new “diversity, equity and inclusion competencies” for medical students, declaring that the study of “systems of oppression ... deserves just as much attention as the latest scientific breakthroughs.” This has destroyed the credibility of the expert class among ordinary Americans, and rightly so. But it has also created a void eagerly filled by extremists and charlatans peddling conspiracy theories to which many conservative populists have proved susceptible. Of course, as a conservative publisher tweeted, it should not follow that because you rightly distrust the medical and media establishments you instead “totally trust what this random guy on YouTube is saying.” Unfortunately, it has. But which came first: the penchant of right-wing populists for conspiracism, or the penchant of learned liberals to beclown themselves?

I can understand how you can be skeptical of the CDC, the New York Times, and your doctor. Heck, I endorse it. They are all capable of dissembling and misleading. What I can't understand is how you then think, "I totally trust what this random guy on YouTube is saying."

— Eric Nelson (@literaryeric) August 2, 2021

Beyond these considerations, however, the more fundamental reasons why the Republican Party should continue to embrace populism are because it’s good politics and good policy. This is where Republican voters are and have been for some time. More importantly, it’s where the key swing voters in the electorate are.

Let’s start with the Republicans. As New York Times political analyst Nate Cohn writes, the 2020 election was “only the latest manifestation of a half-century trend: the realignment of American politics along cultural and educational lines.” In 2020, white voters without college degrees supported President Trump over Joe Biden by a 65 percent to 33 percent margin, while college-educated whites opted for Biden by 57 percent to 42 percent. Non-college whites made up 58 percent of Trump voters but only 27 percent of Biden voters. This was almost exactly the reverse, Cohn notes, of the class breakdown of the vote when John F. Kennedy narrowly defeated Richard Nixon 60 years earlier.

During the intervening years, millions of blue-collar “Reagan Democrats”—repelled by increasing Democratic radicalism on a broad range of cultural issues such as crime, welfare, permissiveness, and patriotism—moved to the Republican Party and became its base, transforming it from a permanent minority party of the country club set to a functional majority party of the working and lower-middle classes. However, these voters maintained their support for traditional Democratic social welfare programs like Social Security and Medicare. At the same time that working class voters were becoming Republicans, the affluent and the business community were moving dramatically to the cultural Left to become Woke Capitalists who serve as the financial mainstay of the Democratic Party and the enforcers of authoritarian progressive orthodoxy.

This realignment created an unsustainable situation in which old-line business-oriented GOP leaders fell increasingly out of step with both the financial interests and the cultural values of their own voters. John McCain denounced progressive taxation as “socialism” but refused to denounce Barack Obama’s association with Rev. Jeremiah “God Damn America!” Wright. Mitt Romney inadvertently belittled much of the Republican base, as Michael Brendan Dougherty pointed out in a perceptive 2015 column about Trump, when he infamously branded 47 percent of the American public as “takers” for receiving government benefits.

Trump, on the other hand, in addition to transgressing all the politically correct niceties on most social issues, blasted “hedge fund guys getting away with murder” and, alone among GOP candidates, pledged to preserve Social Security. This combination of views resonated with not just the GOP base but the general electorate as well. According to a Voter Study Group report, 73 percent of voters are liberal on economic issues such as taxes and inequality but 52 percent are conservative on social issues such as abortion, LGBT matters, and immigration.

These majorities are comprised as follows: across-the-board conservatives are 23 percent of the electorate; across-the-board liberals are 44 percent; while “the sweet spot in American politics, the place where elections are won,” as F.H. Buckley terms it, “is the socially conservative and economically liberal quadrant” consisting of 29 percent of voters. Pulling up the rear are the fashionable libertarian elites, socially liberal but fiscally conservative, who account for less than four percent of the electorate—“an army of generals without any troops behind them” Buckley calls them.

You may have seen the report’s chart illustrating this breakdown. Those are the lonely libertarians in the lower right quadrant:

While elections turn on many factors, it’s probably no coincidence that Trump, who hit the sweet spot, won in 2016 and did better in 2020 than McCain and Romney before him, despite all his self-inflicted wounds. In any event, the party can’t risk going back to the days of either Paul Ryan economics or the soft social liberalism of the post-Romney-Ryan “autopsy.”

Beyond the politics, though, maintaining a populist approach is the right thing to do in terms of policy, particularly for the non-affluent families who now dominate Republican ranks. And it is in no way inconsistent with the traditional conservatism that focused on non-market institutions like religion and the family before the modern Right allied with corporate interests. As conservatives like Oren Cass have argued, the Reaganite tax-cutting and budget-cutting policies that may have been appropriate to jumpstart the economy in the 1980s no longer make sense 40 years later when the rise of globalism and disappearance of blue-collar manufacturing jobs has led to a sharp increase in inequality between upper-income households and everyone else.

Tucker Carlson may now be leading populists down Putinist rabbit holes, but he was onto something three years ago when he observed that corporate abandonment had led to the same devastation and family breakdown in rural white America today as misguided liberal social programs had in urban black America 40 years ago. Of the economic philosophy that allowed this abandonment, he declared:

[M]arket capitalism is not a religion. Market capitalism is a tool, like a staple gun or a toaster. You’d have to be a fool to worship it. Our system was created by human beings for the benefit of human beings. We do not exist to serve markets. Just the opposite. Any economic system that weakens and destroys families is not worth having.

In this economic and political environment, the GOP, far from abandoning Trumpian populism, should, as I’ve written elsewhere, go beyond it to explicitly break with the old pro-business and “free market” orthodoxies on economic issues like tax fairness and healthcare that impact our voters. We should, for example, drop our opposition to Obamacare until we have a viable replacement that leaves no one uncovered and no one worse off. We should consider a modest wealth tax on the super-rich, given that the nation has long relied on a far larger and more regressive wealth tax (the property tax) on the one form of wealth possessed by large numbers of middle-class Americans. And we should equalize the treatment of earned and investment income, on the theory that George Soros and Meryl Streep should pay the same rate on their portfolios that a West Virginia coal miner or a Staten Island sanitation worker pays on his wages.

But what of the downsides of populism of which I acknowledged I had become more mindful at the beginning of this piece? I don’t have a full answer to that. I recognize far more than I once did that those drawn to anti-elitist rhetoric may also be prone to a dangerous conspiracism. At the same time, in an era of Drag Queen Story Hour and gender transition for children, I also think that William F. Buckley Jr.’s famous quote that “I would rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone directory than by the Harvard faculty,” is more true than ever. The central populist conservative truth of the last half century is that the people are right far more often than the self-styled “experts.” I still believe that, but I would just add that they’re sometimes wrong.

II. Populism is dangerous but it should not be ignored

Bo Winegard is an essayist and holds a PhD in social psychology. You can follow him on Twitter @EPoe187.

Populism is a symptom of a disease; it is not the cure. Like other symptoms, it communicates an underlying malfunction, a breakdown in health. It may impel responses that promote convalescence. But if indulged and nurtured, it can exacerbate the disease because it is, by its very nature, a divisive and myopic political style. Although it can be right-wing (or left-wing), it is not conservative, it is radical, railing against a deceitful, superannuated elite and their corrupt institutions. Inevitably, this means that it often derides tradition, respectability, and the status quo. Furthermore, it often promotes a cultish loyalty to a strongman believed to have a singular connection with “the people,” and who is thus a messenger of justice and vengeance on their behalf. Populism should, therefore, be rejected by the Republican party. However, it should not be ignored.

Modern American populism—and its most successful manifestation, Trumpism—is a signal of an underlying divide between cultural and political elites and a large part of the population. This divide is especially acute on issues about demographic and cultural change and political correctness, issues that Donald Trump successfully parlayed on his path to the White House in 2016 (and almost again in 2020). Today, honest conversation about these topics remains difficult; and the mainstream (except for perhaps Fox) media continue to ignore or mislead about race, sex and gender, and other topics that have become sacred values for progressives (and many educated people on both the Left and the Right). For example, candid and serious analyses about racial disparities in crime are incredibly rare; therefore, some of the causes of disproportionate policing are effectively removed from elite discussion, which tends to focus on racism, not underlying differences in offending.

Furthermore, demographic change is almost universally applauded, while the demographic conservatives—those who want slower demographic change because they are attached emotionally and ideologically to current demographic patterns—are routinely assailed as fearful bigots wedded to “whiteness” or “white supremacy.” Elites tend to ignore the symmetry of demographic concerns. That is, they applaud those who want a lower proportion of whites (those who want “more” diversity) but denigrate those who want an equal or higher proportion. These are, however, two sides of the same coin since they both evince a concern about racial representation.

Not only do many Americans feel alienated by modern elites and elite discourse, but they also feel (often correctly) derided by them. They feel mocked, ridiculed, and attacked. They struggle to remain up to date with rapidly changing language norms and are shocked by terms such as “birthing person” or claims such as “men can get pregnant too.” This leads to anger and resentment. Humans care about economic status, but they care about cultural status even more. And many conservative Christians and other traditionalists feel as though they are losing cultural status. So, they want to fight back and to poke a stick into liberals’ judgmental eye, and they delight in the fiery language of fulminating populists.

All societies have conflicts and divisions, of course. But when the gap between educated elites and the rest of the population grows into a yawning abyss, and when the values and lifestyles of each become foreign to the other, then society is imperiled by disease. Populism arises as a symptom of this disease and can, therefore, be a beneficial warning about social dysfunction. But like inflammation or pain, the appropriate response is to address the underlying ailment, not to laud and encourage the symptoms, thereby nurturing and relishing the pain.

Populism is Manichaean, sharply dividing the world between evil elites and the righteous masses. This may be understandable when the values of the elite have sharply diverged from the values of many people, but it does not encourage compromise or a diffusion of tensions. On the contrary, it often provokes a hostile reaction as those who support the status quo battle to defend their positions and privileges. Obviously, political conflict is unavoidable. Absolute unity is impossibly utopian. Even if it were attainable, it would lead to a stagnant society. Equally obviously though, too much conflict and too much division can rend a society, leading to political sclerosis, breakdown, and even civil war.

Populism also has a peculiar tendency to promote a cult of personality around a strong leader who claims to channel the people’s will. This kind of adulation and deference is rarely healthy.

Authoritarians and demagogues quickly grasp the benefits of appealing to the inchoate anger of the masses, becoming dangerously powerful, and transgressing important norms. This is what Alexander Hamilton, for example, worried about when he wrote, “of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.”

Trump, although hamstrung by his own narcissism and idiosyncratic obsessions, is a good example of this. He is boorish, corrupt, and thoroughly uninterested in American norms and traditions. But he does have a remarkable instinct for what a particular segment of the population wants. And he gives it to them (or, at least, he says he will) shamelessly. His character flaws and his flagrant disregard for “respectability” may allow him to be blunt about important issues that other politicians have avoided. But these flaws also led him to promulgate implausible theories about the 2016 and 2020 elections, declaring that he won both in unprecedented landslides. More consequentially, he declared that the 2020 election was stolen from him—rhetoric that ultimately culminated in the riot at the Capitol.

Today, Trump remains the head of a new, populist Republican Party—a man whose vindictiveness and unquenchable desire for personal fealty have shaped and disfigured the GOP. Although this is not necessarily a direct result of populism, it is a predictable effect and a constant danger for any populist coalition.

Many Republicans (especially intellectuals and pundits) find Trump insufferable—they loathe him and his petty grievances. But they do like that he fights; they do like that he is killing the old party of fancy suits, tax cuts, and military interventionism; and they do like that he has excited many once-apathetic voters. And so, they hope to preserve his attitude, his fractiousness, his instinctive populism, while escaping his obvious limitations. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis is probably best placed to pursue this project. Thus, many who want the GOP to continue to embrace populism want it to embrace DeSantis in 2024.

This is understandable and eminently defensible. I would likely vote for DeSantis myself, although I do worry about his ability and his willingness to combat lies about the 2020 election. Like those who support populism, I worry about the widening cultural gulf between elites and many ordinary Americans, between college educated people and the rest of the country. And like those who support populism, I think the GOP must fight harder to preserve and promote traditional American values. However, as the party moves past Trump, I hope that it will also temper its populist rhetoric and fury.

Ultimately, the only way to promote and preserve traditional American values is to persuade people that they are worth preserving. And the incendiary rhetoric of populism is not particularly useful for that task. It satisfies an immediate urge to raise a middle finger to supercilious elites—a pleasure that is easy to condemn but difficult to dissipate—but it does not produce stable compromises that alleviate hostilities.

Abhorring the establishment media, corrupt universities, and the stultifying status quo is not a substitute for a policy platform. And however obnoxious and wrongheaded educated elites can be, however bizarre their ideologies, populists can be equally misguided, equally deluded, equally enamored of implausible theories. For every bureaucrat who believes that sex differences are largely mythical, there is a populist consultant who believes that the Democrats engineered a coup d’état in 2020. For every college professor who believes that America is seething with white supremacists, there is a populist radio host who believes that the FBI is part of a nefarious deep state that wants to destroy Trump and his supporters.

Populism is not the cure. It is a symptom. We ignore it at our peril. But we also embrace it at our peril. The trick is to steer a middle course between combat and compromise, pluralism and unity, anger and optimism. I have no idea what that will look like. But I know that it doesn’t look like Trump, and it also doesn’t look like Mitt Romney.

III. The GOP must move on

“Publius” is a pseudonym.

The Grand Old Party is at a crossroads, confronted by the possibility of a second Trump presidency and a return of noxious elements within the “MAGA” movement. In 2016, many conservatives like me were disturbed by Trump’s rhetoric and by the seedy underbelly of his movement, but we held our noses and voted for him anyway. With his first administration now receding in the rearview mirror and the possibility of a second looming, it is time for some searching reflection on what we’ve learned.

We face unprecedented challenges, domestically and abroad. Our national economy has entered recession territory and is struggling to regain its footing post-pandemic. Several hundred thousand small businesses have closed in the past few years. Inflation is at a historic high. So is government spending. Our national debt is now over $30 trillion. Illegal immigration is also at record levels, placing burdens on social safety nets and already-failing public schools. Violent crime is on the rise. Drug and alcohol abuse is increasing—over 100,000 Americans died from overdoses last year. Globalization is continuing to increase economic interdependence worldwide. Russia is at war with Ukraine. Tensions are high with China. Climate change is happening but Americans are deeply divided over what to do about the threat it poses. These issues weigh heavily on our collective psyche and they are driving people and communities apart. However, Trump’s brand of populism is not the solution to these problems—it will only exacerbate them.

The term “populism” has been around since the late 1800s and the rise of the left-wing, agrarian Populist Party. Word usage trackers reflect a dramatic, sustained increase in its use starting around 1960 and extending through 2000. There has been a meteoric increase in usage since the turn of the millennium, no doubt reflective of the maturation and ubiquity of the Internet. Today, the term is casually tossed around as if everyone knows precisely what it means. But strangely, it is hard to find an agreed-upon definition and nearly impossible to find one that encompasses the two dominant strains currently at work and at odds in American politics.

Modern American populism is perhaps best defined as a political strategy that seeks to capture a groundswell of resentment or fear within a segment of society and achieve critical mass through manipulative appeal to emotion or tribal instinct. The resulting political movements frequently have charismatic leaders who express grievances through conspiratorial or wildly hyperbolic claims, and who purport to be uniquely qualified to save the masses from some purported evil or injustice. They all have scapegoats, often “establishment” government officials or “elite” private-sector interests. The “left-wing” and “right-wing” designations denote a party orientation rather than dogmatic adherence to any particular philosophy, ideology, or policy.

On the Right, we have a nationalistic populist movement led by a charismatic and mercurial former president. The so-called MAGA movement picked up a few pieces of the Tea Party and now pits the cultural and economic interests of American working-class families against a cornucopia of malevolent forces, including illegal immigration, corrupt government bureaucrats and institutions, the “fake news” media, and more recently, “woke” businesses.

Since 2015, Donald Trump has amassed an impressive and well-documented record of comments that a large segment of the country views as either absurd, unprofessional, intentionally offensive, or flatly dishonest. But Trump’s divisive rhetoric, his many detractors insist, pales in comparison to the “Big Lie” and the role Trump played in the insanity that followed the 2020 election. Regardless of one’s views on his accomplishments—and there were some—it is hard to deny that Trump has been and remains a corrosive influence on public discourse, interpersonal relations, and our political system.

On the Left, an equally pernicious strain of populism arose from the ashes of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Complaints of income inequality and corrupt oligarchic business leaders have since been jettisoned in favor of insidious identity concerns, but the venom from the Left is as now corrosive and dangerous as Trump’s. During the 2012 election campaign, then-Vice-President Biden infamously told a diverse crowd of supporters, including many African Americans, that Mitt Romney wanted to “put y’all back in chains.”

Left-wing rage has been further stoked and redirected not only to Trump, but also to his supporters, whom Democrat leaders and supporters decry as dangerous racist, xenophobic, science-denying, religious zealots. From Hillary Clinton’s notorious “basket of deplorables” remark during a campaign speech in 2016 to President Biden’s recent call for voters to save democracy from “semi-fascism,” the overheated rhetoric on the Left now identifies Republican voters as existential threats. Our sitting president, in an effort to mitigate anticipated midterm losses, recently declared that “the very survival of our planet is on the ballot.” In other words, “only Democrats can save the human race from climate change and certain extinction if the keys of power are handed over to Republicans.”

Some may quibble with the notion of whether the tactics and movement within the Democrat party are technically “populist,” but there is little doubt that our house is more divided now than it has been since the mid-1800s. Growing bipartisan fears of looming political violence are not completely unfounded, but they are exaggerated. Many Americans are tired of the rancor and want our leaders to dial back the divisive rhetoric and work together to find common ground and solutions. Donald Trump and right-wing populism are not the answer to this problem.

Conservatives must take great care when selecting our next leader. We should demand a candidate who reflects our beliefs and values in word and deed, who has the character and wisdom expected of the leader of the free world, who has the compassion and conviction needed to repair the deep fissures, fear, and resentment currently plaguing our society, and who has the courage and vision to unite our county and lead us through the trials ahead.

The GOP should, of course, continue to adopt policies that will strengthen families, communities, and the market economy. But it must eschew divisive rhetoric and embrace an attitude of compromise and change to meet the extraordinary challenges of our times. As someone smart once observed: A state without the means of change is without the means of its own conservation.