Editorial

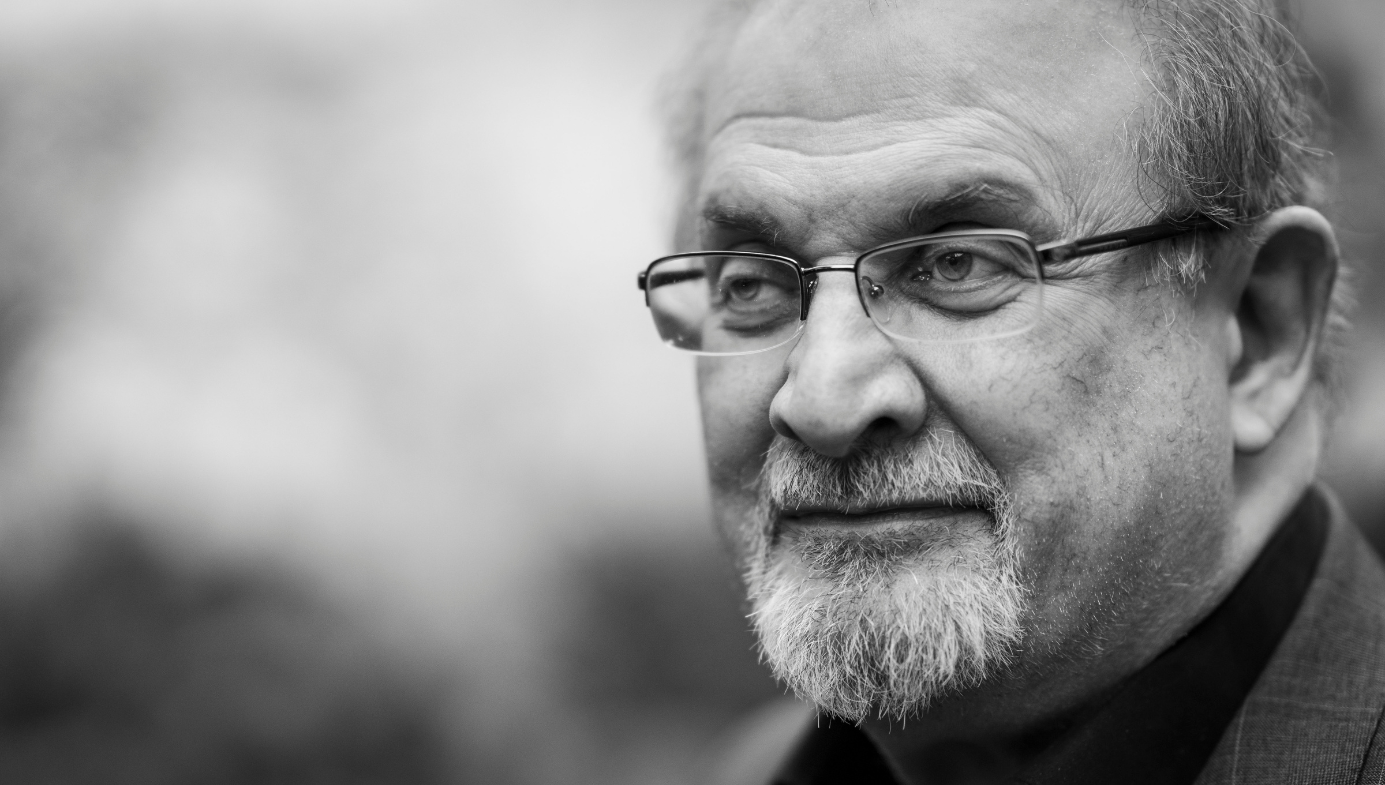

Rushdie’s Moral Heroism

The attempt on the great writer’s life illustrates the dedication with which fanatics pursue the objects of their hatred.

Thirty-three years ago, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a religious decree suborning the murder of author Salman Rushdie for writing The Satanic Verses, a work of magical realism partly inspired by the life of the Prophet Muhammad. A multi-million dollar bounty was offered by the 15 Khordad Foundation, a revolutionary organization supervised by the Supreme Leader, to whoever carried out the sentence of death.

When attempts to appease the regime with an apology were spurned, Rushdie retreated into hiding and was forced to spend the second half of his adult life under threat of assassination. As part of an attempt to restore diplomatic relations with Britain in 1998, the Iranian government of Mohammad Khatami indicated that it would no longer support Rushdie’s murder. Three years later, Khatami declared the matter “closed.”

Iran’s religious leaders, however, are a good deal less interested in the requirements of international diplomacy, and have been remarkably forthright in saying so to anyone who cared to listen. Khomeini’s successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has repeatedly stated that the fatwa will not—indeed, cannot—be lifted, even if Rushdie “repents and becomes the most pious Muslim on Earth.” Just three years ago, the Supreme Leader’s Twitter account was briefly locked after it posted the following tweet:

Although important details are yet to emerge, pronouncements of this type almost certainly help explain why a 24-year-old man named Hadi Matar attacked Rushdie at a literary festival in Chautauqua, NY, on Friday, August 12th. Matar rushed the stage upon which Rushdie was seated, and stabbed the writer repeatedly in the neck and abdomen until the attacker was physically restrained by attendees. A grim irony: Rushdie was reportedly waiting to deliver a lecture in which he would describe the United States as a safe haven for exiled writers and artists.

Rushdie’s attacker has been taken into custody and charged with attempted murder, but his victim sustained serious injuries during the frenzied assault. Later that same evening, Rushdie’s agent, Andrew Wylie, delivered the distressing news that “Salman will likely lose one eye; the nerves in his arm were severed; and his liver was stabbed and damaged.”

The Satanic Verses was published in 1988. The following year, it was banned in India, and copies were burned during street protests in Bradford, UK. An American Cultural Centre in Islamabad was attacked after the book’s publication in the United States. Khomeini’s fatwa was broadcast on Iranian radio on February 14th, 1989:

We are from Allah and to Allah we shall return. I am informing all brave Muslims of the world that the author of The Satanic Verses, a text written, edited, and published against Islam, the Prophet of Islam, and the Qur’an, along with all the editors and publishers aware of its contents, are condemned to death. I call on all valiant Muslims wherever they may be in the world to kill them without delay, so that no one will dare insult the sacred beliefs of Muslims henceforth. And whoever is killed in this cause will be a martyr, Allah willing. Meanwhile, if someone has access to the author of the book but is incapable of carrying out the execution, he should inform the people so that [Rushdie] is punished for his actions.

A wave of bloodshed ensued. Rushdie’s Japanese translator was murdered, his Italian translator was stabbed, and 37 people perished in a fire targeting the book’s Turkish translator. While the violence and threat level appeared to abate with the passage of time, allowing Rushdie to emerge from hiding and re-engage with public life, his growing sense of security proved to be illusory. Indeed, the intervening years taught the most alarming lesson of all—that no-one marked for death can ever afford to lower their guard or return to what Rushdie called “a normal life.”

Rushdie is not the only person Iran has sought to terrorize. And the murderous fanaticism of its leaders remains in evidence, even as it seeks to renegotiate an agreement with the West regarding its nuclear program. American law enforcement officials have recently uncovered assassination plots by operatives associated with the Iranian regime against Donald Trump’s former National Security Advisor, John Bolton, dissident Iranian journalist Masih Alinejad, and Iranian-American poet (and Quillette contributor) Roya Hakakian. Writing in The New York Review of Books a year ago, Hakakian relayed the story of her 13-year-old child opening the door to FBI agents, who then informed Hakakian that Iranian operatives were concocting a plan to kill her.

In a timely essay for Quillette, published in May, Paul Berman observed:

Roya Hakakian and Masih Alinejad happen to be friends, as Hakakian noted in the New York Review, and the combined threats against them suggest a broader policy of violence and intimidation on the part of the Islamic Republic and its operatives in the United States.

This is a policy aimed not just at a couple of inconveniently articulate emigrés, but at the larger circles of the Iranian emigration in America and everywhere else, whose members are bound to pause an additional thoughtful moment before piping up in public about life and oppression back home in far-away Iran. The policy is a display of power. It terrorizes. It succeeds at doing this even if any given plot is foiled, or is suspended, or is merely intimated.

We do not yet know the nature of the relationship—if any—between the Iranian government and Rushdie’s attacker. Early news reports indicate that, “Matar has made social-media posts in support of Iran and its Revolutionary Guard, and in support of Shi’a [Islamist] extremism more broadly,” which could point to Iranian inspiration rather than direction. Either way, the attempt on Rushdie’s life and the sheer ferocity of the attack illustrate the dedication with which fanatics pursue the objects of their hatred, even those who produce works of fiction.

Rushdie understands as well as anyone that this threat is by no means unique to the Islamic Republic of Iran. It issues from adherents of all kinds of radical Islamic movements. In 2005, during the controversy that followed the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten’s publication of 12 editorial cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad, Rushdie was one of 12 signatories to a defiant manifesto titled “Together Against a New Totalitarianism,” the full text of which appears below:

Having overcome fascism, Nazism, and Stalinism, the world now faces a new global totalitarian threat: Islamism. We writers, journalists, and intellectuals, call for resistance to religious totalitarianism and for the promotion of freedom, equal opportunity, and secular values for all. Recent events, prompted by the publication of drawings of Muhammad in European newspapers, have revealed the necessity of the struggle for these universal values.

This struggle will not be won by arms, but in the ideological arena. It is not a clash of civilizations or an antagonism between West and East that we are witnessing, but a global struggle between democrats and theocrats. Like all totalitarian ideologies, Islamism is nurtured by fear and frustration. Preachers of hatred play on these feelings to build the forces with which they can impose a world where liberty is crushed and inequality reigns.

But we say this, loud and clear: nothing, not even despair, justifies choosing obscurantism, totalitarianism, and hatred. Islamism is a reactionary ideology that kills equality, freedom, and secularism wherever it is present. Its victory can only lead to a world of injustice and domination: men over women, fundamentalists over others. To counter this, we must ensure access to universal rights for the oppressed or those discriminated against.

We reject the “cultural relativism” which implies an acceptance that men and women of Muslim culture are deprived of the right to equality, freedom, and secularism in the name of respect for certain cultures and traditions. We refuse to renounce our critical spirit out of fear of being accused of “Islamophobia,” a wretched concept that confuses criticism of Islam as a religion and stigmatization of those who believe in it.

We defend the universality of freedom of expression, so that a critical spirit can be exercised in every continent, with regard to each and every abuse and dogma. We appeal to democrats and independent spirits in every country that our century may be one of enlightenment and not obscurantism.

Signed by: Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Chahla Chafiq, Caroline Fourest, Bernard-Henri Lévy, Irshad Manji, Mehdi Mozaffari, Maryam Namazie, Taslima Nasreen, Salman Rushdie, Antoine Sfeir, Philippe Val, Ibn Warraq.

Salman Rushdie has risked everything for his art. Like Jyllands-Posten editor Flemming Rose, the slain cartoonists and satirists at Charlie Hebdo, and numerous other courageous writers, thinkers, artists, and intellectuals hunted across the globe for violating ancient taboos against blasphemy, he has stood up for free thought and expression, even as others have disgraced themselves by offering excuses on behalf of those who perpetrate lethal violence in the name of religion.

Rushdie’s steady courage and reliable willingness to defend individual liberty have ensured his status as one of the great moral heroes of our time. “A poet’s work,” remarks one of his characters in The Satanic Verses, “is to name the unnameable, to point at frauds, to take sides, start arguments, shape the world and stop it from going to sleep.” Rushdie has done all those things. And it is a tragedy that his dedication to these noble pursuits has cost him so much.