Politics

From Football to Fiasco

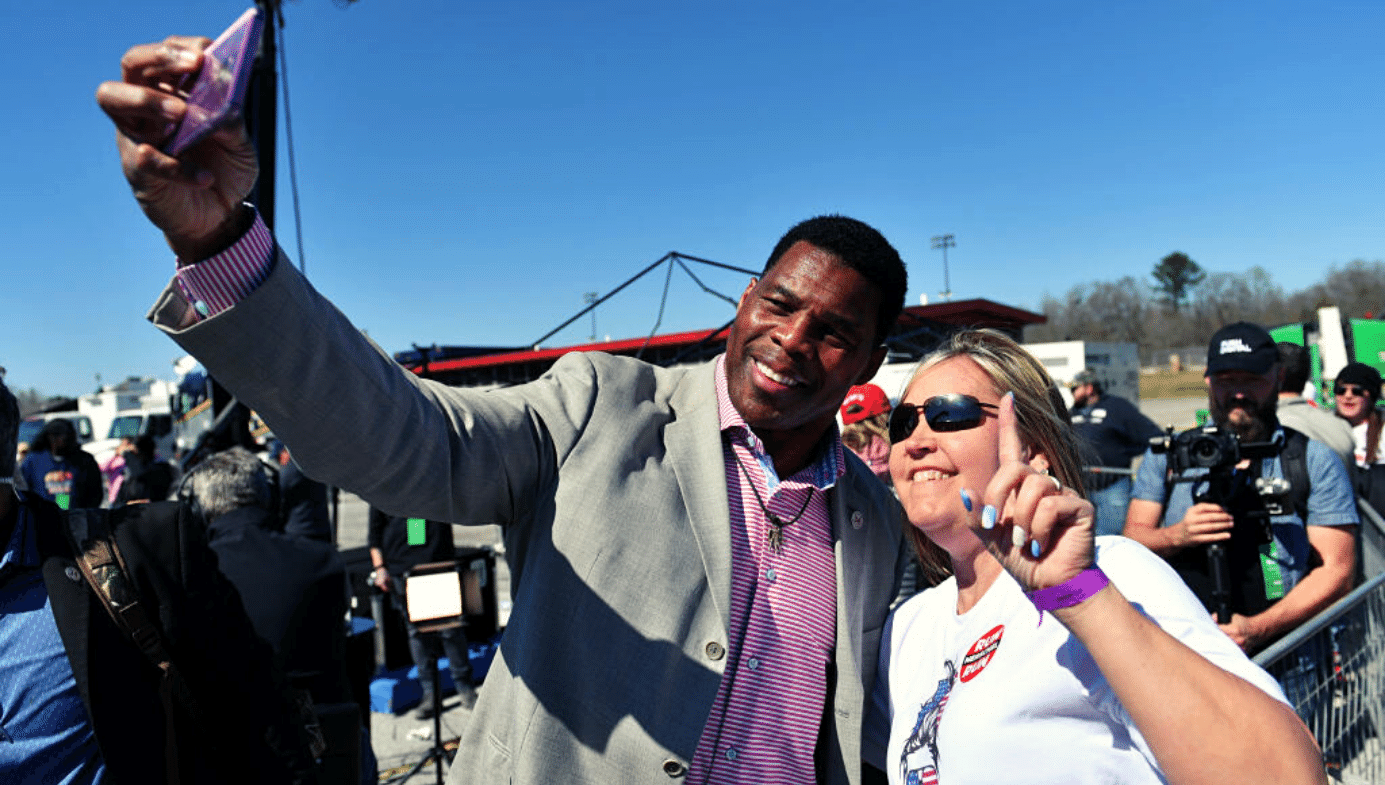

Herschel Walker is discovering that moving from professional football to politics isn’t as easy as it looks.

There is no shortage of media coverage portraying Herschel Walker as an imbecile and fabulist. The former NFL star is 60 years old, played pro football from 1983 to 1997, made about $US15million during his career, and was encouraged to run for the US Senate in the state of Georgia by former president Donald Trump. His campaign, however, has been a calamitous series of errors—his lies about graduating from college, his views on gun control and climate change, and his peculiar thoughts about China’s “bad air” have all drawn a flood of media derision.

A New Republic headline announced that, “Herschel Walker Is Running to Be the Senate’s Dumbest Liar.” Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson has warned that, “If Herschel Walker wins in Georgia, America will have lost its mind.” And Deadspin has called Walker “the ultimate dumb jock.” I do not find this coverage offensive. Walker has indeed said many deeply stupid things during the course of his campaign, and has never been known as a great thinker in any case. Among his many and various faceplants, he has blasted absentee fathers only for it to emerge that he has three kids of his own whom he apparently never sees.

I don’t want to get into itemizing all the idiotic things the guy has said during his gaffe-prone campaign. As a journalist who has spent time in locker rooms with jocks like him, and on the campaign trail with equally ignorant politicians, idiocy does not interest me. (I once asked a police officer in Texas why he was running for sheriff, and he said he’d have to check with his campaign manager and get back to me.) But I do find myself wondering why ex-jocks have not made more frequent forays into the political arena. After all, successful election campaigns require name recognition, cashflow, and stamina, and retired professional athletes in the United States enjoy all three. The first two—fame and money—have certainly increased in the past few decades as pro sports moved ahead of the movies and TV shows in terms of ratings and profits.

People in the business community usually start their political careers in their 30s and 40s. So why are more athletes—who generally retire from sports at that age anyway—not also moving into politics? Basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had this to say on his Substack recently:

I’ve always argued that it’s the responsibility of highly paid athletes to use their privileged platform to better the lives of others. That’s just the right thing to do. It also has the added benefit of elevating professional sports in the eyes of the public from being just greedy profit conglomerates raking in billions to being integral boosters of the communities that finance them. And it also elevates athletes from stereotypes of dumb gym rats with more bulging muscle than brain matter to grateful and compassionate neighbors.

…

Yet, sometimes athletes and former athletes want to take advantage of their fame by running for political office. That’s where things get tricky because, depending on the office, that’s a lot of power suddenly in the hands of someone just because they could slamdunk a basketball, slug home runs, or run touchdowns. None of these skills preclude someone from doing well as a politician, but neither do they add anything.

Abdul-Jabbar makes a number of good points here, but the combination of sports celebrity and elected political power is hardly a worry since ex-athletes don’t play much of a role in US politics. Walker is something of an aberration.

Much of this has to do with the fact that the skills most important to success in elite sports are related to what scientists call “muscle memory.” As Christopher Mance II, a former wrestler and self-styled “mental skills coach,” puts it, “In sports, the term muscle memory typically refers to one’s ability to execute a skill flawlessly without thinking. It takes an enormous number of repetitions to commit a complex skill to one’s muscle memory.” One researcher observed, “In most sporting competition, athletes are at a disadvantage if they need to think before moving.”

I’ve found I get bored talking to athletes about their groin pulls and the dedication they bring to their work, but most of the time I do it anyway. I’ve always preferred trying to get inside the brain of those able to accomplish feats of strength and skill. But this is generally a dead end. While most can explain why chicken breast is their main protein source (or at least provide their hired trainer’s protein explanation), they have a hard time articulating why they cut this way or that, made the no-look pass no one else saw coming, or hit a 400-foot home run in extra innings when a 100-mph fastball gave them only a few milliseconds of reaction time. They simply haven’t thought that way in decades, if ever.

When I was writing a profile of NBA player Kyle Korver, I realized why this was. The six-foot five-inch Korver, who started as an also-ran in the league, lasted 17 years and made an estimated $82 million in that time. When I began asking him how he was able to do that, he tried to explain how the technique he developed for shooting his three-pointers made up for his relative lack of height and speed. It soon became apparent that the only way he could show me what he meant was by demonstrating on the court. The ball needed to be passed into his right hand at precisely the right time and precisely the right height so he could get off his shot quickly without getting blocked. That way, he could make about 50 percent of his shots and keep his place in the league.

So what does all this have to do with Herschel Walker running for the Senate? The problem Walker faces is that professional US athletes have existed in a bubble since grade school, receiving preferential treatment from day one. Today, they live in an age of prerecorded podcasts and carefully curated Instagram posts which allow them to exercise tight control over their public image. This makes running for political office extremely difficult because the key to success is thinking through programs and policy and explaining them publicly, skills that star athletes have never really had to develop.

The media and business arrangements of the leagues, teams, and pro athletes mean it’s likely that Herschel Walker never had to answer any questions any more complicated than whether his foot still hurt after it got stomped by a 300-pound opponent. No one in the sports media ever bothered to ask whether or not he was telling the truth about graduating from the University of Georgia, or serving as a police officer and training to be an FBI agent. That simply wasn’t part of the deal.

Was being an African American from the South a factor in all this? Perhaps. The sociologist Harry Edwards has pointed out that Walker never involved himself in civil rights protests or other racial controversies because it might have hurt his career, so he isn’t used to navigating the fraught public debate about race:

“Herschel Walker,” Harry Edwards, the Black sociologist and longtime advocate for activism among Black athletes, told the Atlanta Constitution in 1986, “was in good shape in Georgia as long as he was ‘the right kind of n-----.’ It’s as simple as that. That’s something Black people recognize universally in this society. As long as he restricted himself to activities and comments about what was happening on the football field, he was OK. They were demonstrating against racial injustice in his hometown, and he couldn’t come out and make a statement about it because he was eminently concerned about being above reproach as far as his credentials relative to being ‘the right kind of n-----.’”

“Down in Georgia at that time they didn’t call you Black. They called you a n-----,” Edwards told me recently. “He was simply saying, ‘I’m not going to get involved with activism, because it’s not about Black folks, it’s not about the state of Georgia—it’s about me. And as long as they think that I’m a good n-----, I got a chance.”

Edwards is probably being unfair. We are who we are. Walker was seen as a star athlete from the beginning and duly placed on a pedestal, and in that role he made a lot of people rich and a lot of fans happy. He was probably required to do less studying than his fellow students, so he wasn’t asked for his political opinions and didn’t feel compelled to offer them. Now he is finding that he is not especially good at it, partly because he’s never had the practice.

It is true that people who make a lucrative living that involves a lot of public exposure and attention might be expected to seek a profession that offers more of the same when they retire. But most US athletes understand that getting into politics requires a different skillset, which is why, historically, only a tiny number of American professional athletes have done so (Bill Bradley, Jack Kemp, Alan Page, Dave Bing, and a few others). Herschel Walker is now aware of that, and he has brought in a new campaign team to try and keep his media critics at bay. In order to win in politics, a candidate has to embrace the electorate and answer questions that are not league-approved. They can no longer depend on the adulation that comes with sporting prowess and success.

None of this necessarily means he will lose his race. The polls indicate that it is close, and some Georgians will no doubt vote for him simply because he is the Republican candidate and/or because he is a former football star. Others won’t vote for him for the same reasons. We’ll just have to wait see how that game plays out. But Walker evidently thought that stepping from sports into politics would be easy. He’s discovering that it’s much harder than it looks.