Politics

Against False Privilege

One of the biggest blunders of modern activism is the promotion of guilt and the demand for false privilege.

Prejudice is universal. Growing up a black kid in Ireland, I thought that Jehovah’s Witnesses were odd because they do not celebrate birthdays or Christmases. I looked sideways at caravan-dwelling Irish Travellers (to whom my school friends and I often referred using terms that certainly would not satisfy contemporary high standards of “verbal hygiene”). I had no idea why some Muslim women covered their bodies from head to toe, and if you had asked me to name a particular style of Islamic head covering, I would have floundered, resorting to the Western world’s catchall term of “headscarf” or “hijab.” Contrary to popular belief, the fact that I am a black woman living in a white country does not somehow inoculate me against human prejudice.

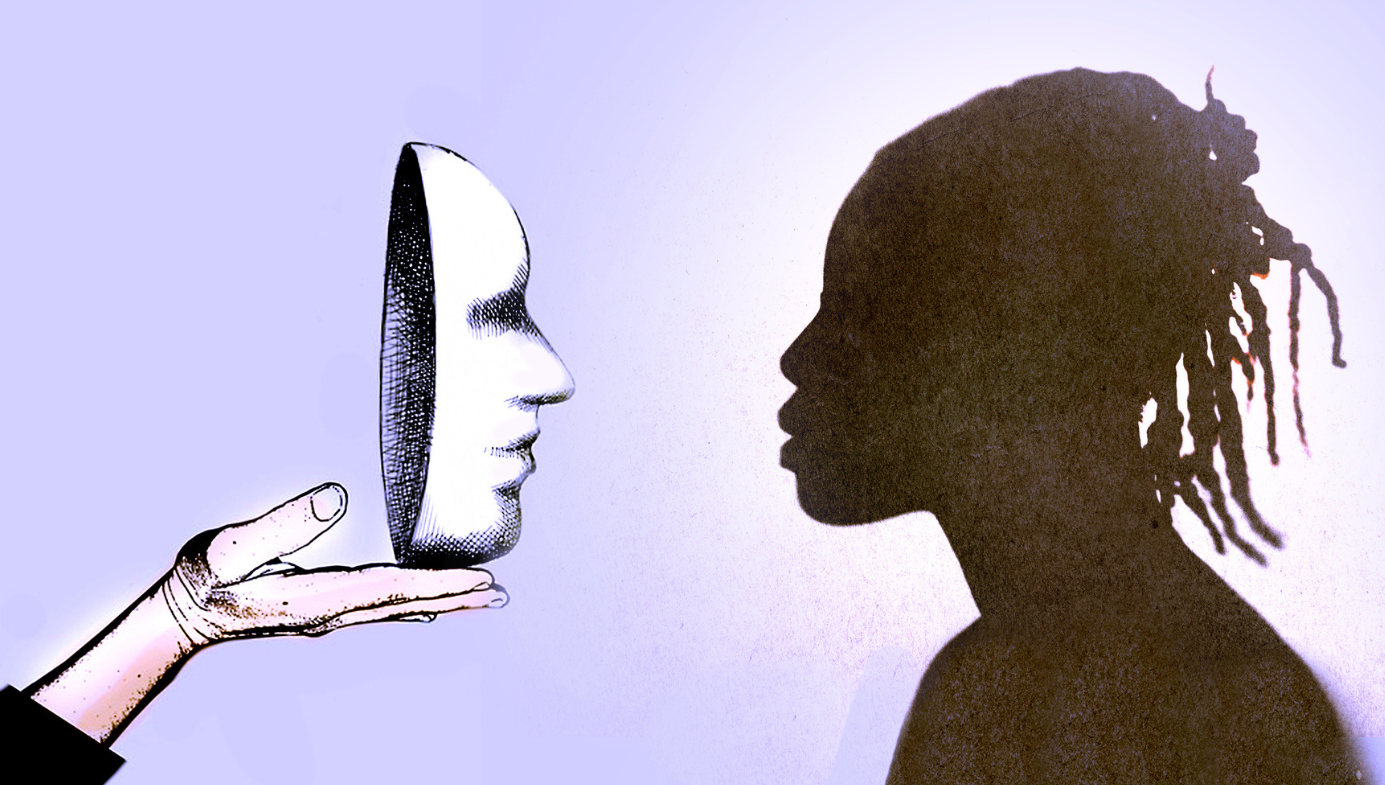

And yet, I’m given to understand that I must know what prejudice feels like more than anyone. One of my graduate teachers once told me that the most offensive thing anyone could ever say to me would be something xenophobic or racist. It did not seem to occur to her that I could be meaningfully insulted in any other way because she seemed to be incapable of seeing anything about me but my “blackness.” Were she to observe me sitting next to a white man, I would be sitting next to a person with a nationality, a particular dress style, an idiosyncratic way of wearing his hair perhaps, and a handful of other visible characteristics—all of which are likely to register before his “whiteness.” I, on the other hand, am nothing more than my skin colour. It is my fundamental descriptor; the only thing that seems to be of any relevance or importance.

“What is it like to date a black woman?” a middle-aged white woman asked my white boyfriend as we sat at a bar. She was riotously drunk and wide-eyed, her face filled not with malevolence but with wonderment. In the stunned silence, she continued, “Why did you fall in love with her? Was it because of her skin?” You might think that the questions she asked are rare nowadays—that they belong to a pre-modern and barbaric kind of thinking that has long since evaporated along with hunter-gathering and nomadic tribalism.

But this sort of thinking is by no means obsolete. What I saw in this drunk woman has always been buried in the private chambers of people’s minds. And it remains there until it’s dislodged by a stiff whiskey and tramples over the fences of social etiquette. Our bodies house the lewdest and filthiest of secrets, but do not be fooled by a quiet, polite, and politically correct exterior. Appraising that 60-year-old woman as she chugged back her Guinness and asked me if black people “bruise,” I decided she was loud, fat, and ugly. Contrary to our own self-flattering notions of refinement and progression, we were both guilty of reducing the other to the sum of her superficial features.

But I can “play the race card.” I might have justifiably called her a racist or a bigot. Had I done so, she would have been powerless to return the accusation. And yet, I also harbour my own brand of fetishes and fascinations. I recall spending an inappropriate amount of time staring at a group of Hasidic Jews in an airport once, riveted by what I thought were impeccably curled sideburns (actually pe’ot, Anglicized as “payot”—a Hebrew term meaning “corner” or “edge”). This is just one of many occasions on which I have looked at a human being as though they were an interesting object. I have lost count of the number of times I have been influenced by my false preconceptions of white people (as though they constitute some nondescript monolithic category).

However, my membership of a supposedly oppressed group licenses me to speak and act with fewer social restrictions. Not only does my race permit me to abide by certain social codes more loosely, but in some cases, it even empowers me to violate those codes with impunity. When I was eight years old, a fat white boy called me a nigger while we were being taught to plant daffodil bulbs in the school yard. In response, I grabbed an enormous fistful of wet dirt, threw it into his muddy face and shouted, “Look who’s a nigger now!” An hour later, my mother arrived to collect me from my white teacher amid a shower of apologies and special encouragement. I was given the day off as a consolation prize. The other kid was sent to the principal’s office.

It did not take me long to realize that my “blackness” was widely considered a kind of extenuating circumstance. Almost any offence can be absolved by my presumed entitlement to retributive justice. I am allowed to throw dirt at other nasty children because the world is racist. When black kids grow up, we are loath to name or challenge this exemption in each other—doing so would be seen as the worst kind of disloyalty. Whites do not publicly challenge it (although they resent it in their private circles) because they are possessed by that most potent of all spiritual poisons: white guilt.

These special dispensations are not reserved exclusively for blacks. They are also granted to the disabled and the queer—anyone who tends, by their very existence, to make others feel guilty. Contrary to popular opinion, neither race nor gender nor disability supplies any of us with the right to be violent (outside of the realm of self-defence) nor to demand special treatment outside of those adjustments which are necessary for levelling the proverbial playing field. So long as we are treated as forgotten, marginalized, and disowned, few of us have dared to speak about the particular kind of privilege that status bestows—the privilege of being somehow unimpeachable.

This exemption may look and feel like privilege, but it is a false kind of privilege. The person exonerated of criminal responsibility by “reason of insanity” is not privileged. Rather, they are judged to have the mental development of a child. When someone is given fewer limits than their peers and coddled when they misbehave, they are subject to diminished expectations which preclude equal dignity. Handling the oppressed with “kid gloves”—appeasing and pacifying them, refusing to take them seriously—pathologizes them. In this way, blackness and disability and transgenderism and gender non-conformity and queerness are reduced to impediments. The guilt and pity that these impediments evoke in those not equally impaired are not the same as compassion.

One of the biggest blunders of modern activism is the promotion of guilt and the demand for this kind of false privilege. Progress cannot occur if it is rooted in the idea that the oppressed are inherently impaired. Progress can only occur on the basis of perceived equality. And equality means treating people equally, which includes being held accountable for wrongful actions. It means being taken seriously. But if oppressed people are to be taken seriously by the rest of the world, we have a duty to speak and act in ways that demonstrate a belief in our own worthiness to be taken seriously. Rather than silencing our critics with epithets, we must engage them in rational debate. We must decline the offer of a free pass, secure in the knowledge that we are not insane or childlike and that we are capable of amounting to something equally great. We must hold ourselves to the same standards we expect of others—standards of which we know that we are capable.

In a speech delivered at a women’s college in 1977, feminist poet Adrienne Rich said:

Responsibility to yourself means that you don’t fall for shallow and easy solutions—predigested books and ideas, weekend encounters guaranteed to change your life, taking “gut” courses instead of ones you know will challenge you, bluffing at school and life instead of doing solid work. … It means that you refuse to sell your talents and aspirations short, simply to avoid conflict and confrontation. And this, in turn, means resisting the forces in society which say that women should be nice, play safe, have low professional expectations, drown in love, and forget about work, live through others, and stay in the places assigned to us.

Part of this responsibility to ourselves is acknowledging that we are all guilty of prejudice. If you have been marginalized, appreciation of this unsettling fact will change the way you speak to others—especially those whom you regard as culpable. Rather than rising to the pulpit or occupying the schoolmaster’s chair, you can stand next to them and describe your experience. You can defend your dignity as an individual with dialogue rather than name-calling (which is, in any case, of limited effectiveness).

The goal is to foster mutual understanding and respect, as opposed to stoking a fire of resentment beneath a veneer of well-rehearsed politeness. While we are demanding that people take us seriously, we should return the courtesy by refraining to offer paternalistic education. Instead, we can tell them how they (as individuals) have offended us (as individuals) without invoking the full weight of the world’s injustice. In this way, we can get to the heart of discrimination without retreating from confrontation on one hand, or engaging in retaliatory violence and abuse on the other.

As paradoxical as it might sound, refusing the free pass and acknowledging one’s own prejudice can lead to the reclamation of real power instead of false privilege. People gain power when they reject guilt and embrace the fruits of responsibility. Good activism does not seek to stymie our progress by stirring up guilt. The late radical feminist Audre Lorde recognized this when she said:

[G]uilt is just another name for impotence, for defensiveness destructive of communication; it becomes a device to protect ignorance and the continuation of things the way that they are, the ultimate protection for changelessness.

We short-change ourselves when all we demand is cheap guilt and appeasement. It is easier for the guilty to pacify and to pet and to change their vocabulary than it is for them to dig into those private chambers and uproot their own prejudices, shameful fascinations, and objectifying fantasies. For them, to smile and to nod and to pretend that they agree is infinitely more convenient. Are we to settle for this kind of shoddy, half-hearted junk-compassion because we are too afraid to struggle towards the real thing? Real equality demands that we hold up our end of the bargain. It demands that we recognize our own tendencies to pin the guilty into a corner and to coerce them into smiling and nodding and pretending that they agree by threatening to cancel them for real and perceived transgressions.

One of the most feared words in the English language today is “racist.” It is a stain that simply will not wash off. We have adapted our language to mitigate our negative judgments of minorities—not because we are really sorry, but because we hope to protect ourselves from being irreparably tarnished. To be accused of being a racist is not just a moral issue, it carries profound social, financial, and political costs.

Increasingly, these accusations are made not in the name of racial justice, they are simply a tool for silencing ideological dissent. Tenured professor Joshua Katz was fired from Princeton this year after he criticized some of the more radical “anti-racist” initiatives proposed in a 2020 open faculty letter (although, the official reason for his dismissal was the resurrection of an old sexual misconduct case for which he had already been sanctioned). Katz is not racist—he simply bristled at minority demands for special treatment like additional pay and holiday time for faculty of colour because he considered them an affront to equality.

Under no circumstances should racial abuse ever be condoned. But too much contemporary black activism employs Manichean efforts to divide humanity into a morally pristine class of minority saints versus an ignominious group of “oppressor” fiends. The saints and the fiends are pitted against one another, and none of us can hear anything over the ensuing din. No one ends up having a real conversation about real racial injustice. No one ends up admitting to the unpleasant yet self-evident truth that all of us are stained. An activist who acknowledges this is a force to be reckoned with, since no one can weaponize that for which you have already taken responsibility.