Science / Tech

Guilty and Insane

Dissociative Identity Disorder and the riddle of human responsibility.

How much of our lives, good and bad, should we credit to our personal decisions, and how much is just the inheritance of our culture, our families, and our parents who have failed their children? … Where does blame stop and sympathy begin?

~JD Vance, Hillbilly Elegy

On May 7th, 1972, Arthur Shawcross raped and murdered 10-year-old Jack Blake in Watertown, New York. Four months later, on September 2nd, he raped and murdered eight-year-old Karen Ann Hill. He was arrested on September 3rd. Because there was no evidence beside his confession, in order to guarantee a conviction, Shawcross was allowed to plead guilty to the lesser charge of manslaughter. He was sentenced to the maximum of 25 years. However, after serving just 14 years of his sentence, he was released on parole. Even though he had been diagnosed by one psychiatrist as a schizoid psychopath, inexperienced prison staff recommended release after concluding that he was “no longer dangerous.” In his book, The Anatomy of Evil, Dr. Michael H. Stone, Professor of Psychiatry at Columbia University, ventured that this was “one of the most egregious examples of the unwarranted release of a prisoner.”

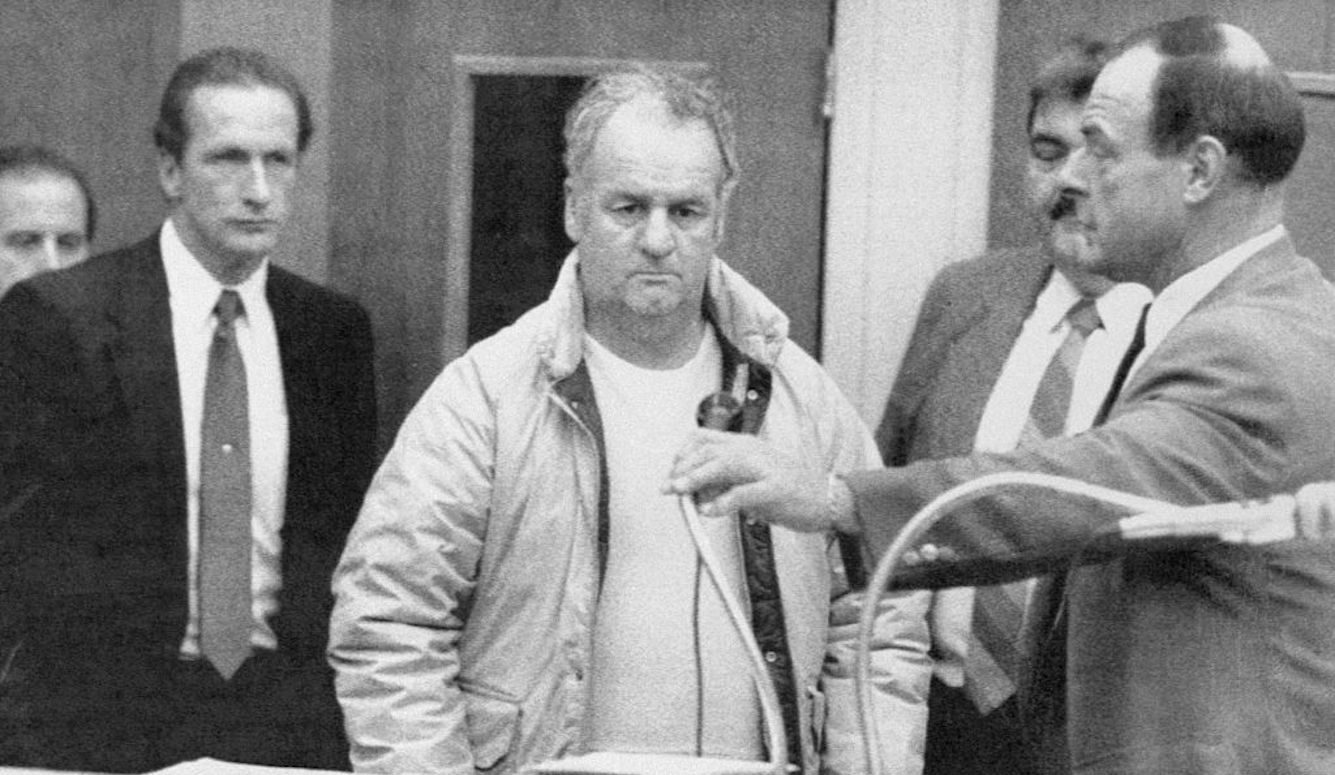

Within a year, Shawcross moved to Rochester, NY, and began a 21-month killing spree that would earn him the nickname the Genesee River Killer. Between March 1988 and his arrest in January 1990, he would murder a dozen women, most of whom were prostitutes. This time, he pled “not guilty by reason of insanity,” and the defense called psychiatrist Dr. Dorothy Otnow Lewis as an expert witness. Lewis testified that Shawcross had a cyst pressing on his temporal lobe and scarring on his frontal lobe—the areas of the human brain responsible for decision-making and self-control—and that, due to the physical and sexual abuse to which he said he’d been subjected by his mother in childhood, he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. More controversially, Lewis testified that this abuse had caused Shawcross to dissociate, and that he moved into a separate, internal personality named “Bessie” when he committed his crimes. On this basis, she argued that he should be sent to a hospital for treatment rather than returned to the prison system.

In his 2020 HBO film, Crazy, Not Insane, award-winning documentarian Alex Gibney examines Lewis’s pioneering career, during the course of which she studied many of America’s most notorious serial killers, including Ted Bundy who murdered more than 30 young women and girls. Gibney shows us excerpts from Lewis’s evidence at Shawcross’s televised 1990 trial, during which she testifies that severe trauma can produce a split in a person’s sense of self. This, she explains, can yield multiple, distinct personalities that consecutively occupy the individual’s consciousness, often with no knowledge of the others. These personalities may each be capable of intelligible discourse—which is to say that, individually, they do not appear to be insane. The shifting personalities, however, makes the constellation quite crazy, especially when a murderer is one of them. In archive footage, we watch Lewis interview Shawcross before the trial, and he appears to transform from one identity into another as they speak—his voice and tone change as he adopts the personality of his abusive mother.

Lewis holds that a diagnosis of Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID, formerly called Multiple Personality Disorder) in murder cases is a mitigating factor, because it calls into question an individual’s responsibility for his behavior when an alternate personality is in control. Since the other personalities have no access to the murderous one, should the individual—who is a constellation of all the characters—suffer capital punishment or life in prison for the behavior of one of them? Especially if the split in the individual’s identity appears to have arisen from a wellspring of traumatic abuse and neglect in childhood?

Hypnosis and partitioned consciousness

By the time I entered high school, I was already reading and studying psychology, and I began to experiment with hypnosis after I stumbled across a book on the topic. In demonstrations conducted on friends and classmates, I found the process to be quite simple, but also that susceptibility ran in thirds. For one-third, there was no clear effect, while another third seemed to experience something different from normal waking consciousness (although it could be hard to distinguish from a willingness to go along with what was expected). One-third, however, readily went into the kind of “altered state” you see when stage hypnotists perform.

In college, where I majored in psychology, one of my professors introduced me to the work of Theodore X. Barber, a psychologist and noted critic of the field of hypnosis. Barber argued that the varied phenomena labeled “hypnosis” could be explained without invoking the notion of an altered state of consciousness. In a review of Barber’s book, Hypnosis: A Scientific Approach, another prominent hypnosis skeptic, Theodore R. Sarbin, PhD, noted that Barber’s work “demystifies and demythologizes” hypnosis, and concluded that, “the construction of hypnosis as a special mental state has no ontological footing.” For Sarbin, human behavior is largely composed of socially constructed expectations and roles. There is no special state in hypnosis, just role expectations that, as in ordinary waking consciousness, shapes the wide range of human behavior, some of which is quite extraordinary.

Nevertheless, the astonishing results of my own experiments in hypnosis suggested to me that some people do indeed enter an altered state. Just as Lewis believed that one part of a person’s split personality could commit crimes of which their other personalities had no awareness or memory, I found that hypnosis could be used to “partition” a subject’s consciousness. A friend whom I instructed to behave like a chimpanzee under hypnosis awoke with no memory of the experience, but it came flooding back to him the following day when the post-hypnotic amnesia broke down. The use of hypnosis as a sedative during surgery in lieu of anesthetic appears to confirm that the process involves a lot more than role expectation. Discrete states of consciousness, it seemed to me, were indeed possible. And if such states could be induced using hypnosis, it is plausible that they could develop in a mind damaged by the kind of physical or psychological trauma produced by childhood abuse.

One of the problems with Lewis’s diagnosis of DID is that part of her examination of Arthur Shawcross was conducted under hypnosis. Was she uncovering an alternate personality? Or was the hypnosis of a susceptible individual inducing the confabulation of an alternate personality? This pitfall can trap even the most experienced psychiatrists and psychologists, even those engaged by prosecutors. During the “Satanic panic” of the 1980s and ’90s, more than 12,000 claims were made about satanic ritual abuse that never actually happened. Many of these accusations were obtained under hypnosis as part of recovered-memory therapy from alleged victims of abuse. Furthermore, Shawcross’s earlier, premature release had already established that he understood how to behave in a manner that matched what others wanted to see.

Skeptics of Lewis’s theories are represented in Gibney’s film by the prominent psychiatrist, Park Dietz. They argue that dangerous men who adopt a DID defense are just play-acting to avoid the death penalty for their heinous crimes. Appearing for the prosecution in the Shawcross trial, Dietz testified that the accused suffered from antisocial personality disorder (APD) and claimed that the DID diagnosis is a “hoax.” Dietz is well-known for this position, and prosecutors routinely call him as an expert witness to discredit an exculpatory insanity defense. Like Sarbin and Barber, he “demystifies” the defense experts’ presentations of a psychotic condition, and reliably concludes that the offender in question understood the wrongfulness of his actions, and that theories to the contrary have “no ontological footing.”

In my career as a forensic psychologist, I’ve treated and evaluated (or supervised the evaluation of) over a thousand extremely violent men, most of whom were sex offenders and dozens of whom were murderers. So, I was familiar with Dietz’s reputation and record. I have only limited information about the Shawcross case, but I find the APD diagnosis to be implausible. I’ve never seen or heard of an APD disordered individual who can drop his antisocial behavior patterns convincingly enough during 14 years in prison to obtain a recommendation for early release, especially after a conviction for murder.

The personality disorder section of the most recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (the DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association requires that the disordered pattern be present in all settings and in all periods of the individual’s life:

A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual's culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood [and] is stable over time. [p. 645, emphases added]

According to the DSM, for a diagnosis of APD, the “pervasive and inflexible” pattern must include at least three of the following:

1. Failure to conform to social norms with respect to lawful behaviors, as indicated by repeatedly performing acts that are grounds for arrest.

2. Deceitfulness, as indicated by repeated lying, use of aliases, or conning others for personal profit or pleasure.

3. Impulsivity or failure to plan ahead.

4. Irritability and aggressiveness, as indicated by repeated physical fights or assaults.

5. Reckless disregard for safety of self or others.

6. Consistent irresponsibility, as indicated by repeated failure to sustain consistent work behavior or honor financial obligations.

7. Lack of remorse, as indicated by being indifferent to or rationalizing having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from another.

Parole boards are by no means foolproof. Cooperative and well-behaved inmates do occasionally secure early release and go on to commit heinous crimes. Nevertheless, in my experience, it is highly unlikely that a prisoner with just three of these “enduring, inflexible, and pervasive” behavior patterns required for an APD diagnosis could fool even inexperienced clinicians after murdering two young children.

But if Dietz’s diagnosis of APD is unconvincing, why was he in such a hurry to dismiss Lewis’s alternative hypothesis? Part of the reason, I suspect, is a fear that acknowledging the possibility of multiple personalities will destabilize notions of free will and responsibility upon which the criminal justice system has traditionally rested. But this is a misguided objection, given our understanding of the limits of human agency.

Free will and responsibility

Man can, indeed, act contrarily to the decrees of God, as far as they have been written like laws in the minds of ourselves or the prophets, but against that eternal decree of God, which is written in universal nature, and has regard to the course of nature as a whole, he can do nothing.

~Baruch Spinoza

The more we study human motivation and behavior, and the more we learn about how the mind functions, the more we find that conscious actions and feelings are only a tiny part of us. For the most part, the mind operates outside of our awareness. I wrote these words as I thought them. But I did not consciously decide to think each word. How could I deliberate about whether or not to think of a word before I was already doing so? The words I’m writing just appeared in my mind in the process of creating this essay. These thoughts are a precipitate of my innate disposition, my personal history, and the immediate moment that includes the preceding thoughts and the point being made.

The more we understand about the world of which humans are a part, the more we learn about the unshakeable laws of cause-and-effect that govern activity, the more we are forced to confront the fact that there is no “ghost in the machine.” All the advances in psychology, neurology, sociology, psychiatry, economics, anthropology, and all the social sciences push back the veil of mystery about the causes of human behavior. There is no homunculus within each of us, independently operating beyond the laws of physics, generating our thoughts and exercising what is generally understood to be “free will.”

In his introduction to The Selfish Gene, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins describes how the survival and replication of our genes governs most of our behavior. His book, he says, is

to be read almost as though it were science fiction. … But it is not science fiction: it is science. Cliche or not, “stranger than fiction” expresses how I feel about the truth. We are survival machines; robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes. This is a truth which still fills me with astonishment. Though I have known it for years, I never seem to get fully used to it.

Sigmund Freud spent his life arguing that people are only dimly aware of the forces outside of consciousness and that these are the most powerful determinants of their behavior. In his essay, “On Narcissism,” he argued that the individual carries out actions

as a link in a chain, which he serves against his will, or at least involuntarily. The individual himself regards sexuality as one of his own ends; whereas from another point of view he is an appendage to his germ plasm, at whose disposal he puts his energies in return for a bonus of pleasure. He is the mortal vehicle of a (possibly) immortal substance like the inheritor of an entailed property, who is only the temporary holder of an estate which survives him.

At the other end of the psychological spectrum, the behaviorist, B.F. Skinner, came to the same conclusion. In his 1971 book, Beyond Freedom and Dignity, he wrote:

Unable to understand how or why the person we see behaves as he does … we are not inclined to ask questions. We probably adopt this strategy not so much because of any lack of interest or power but because of a longstanding conviction that for much of human behavior there are no relevant antecedents. The function of the inner man is to provide an explanation [for behavior] which will not be explained in turn. Explanation stops with him … [H]e is a center from which behavior emanates. He initiates, originates, and creates, and in doing so he remains, as he was for the Greeks, divine. We say that he is autonomous and, so far as a science of behavior is concerned, that means miraculous.

The position is, of course, vulnerable. Autonomous man serves to explain only the things we are not yet able to explain in other ways. His existence depends upon our ignorance, and he naturally loses status as we come to know more about behavior.

In this scene from the acclaimed movie, Waking Life, Richard Linklater brilliantly summarizes the problem of free will and responsibility in a world governed by cause-and-effect:

We may feel free to choose what we want. After all, we do make choices, and we don't feel controlled or pushed around like Dawkins’s gene machine. However, as Voltaire put it, “When I can do what I want to do, there is my liberty for me, but I can't help wanting what I do want.” In other words, we are free to choose according to our desires, but we are not free to choose our desires.

All these thinkers have tried to make us understand that what appears to be independent action or freely willed behavior is actually determined by our innate motives, our current biochemistry, our current circumstances, the neurobiological modifications that our personal experience has induced in our brains, and the evolutionary forces of natural selection. And “None,” wrote the German poet and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.”

Viktor and Lenny

In sharp contradistinction to this conclusion, we have the common experience of making decisions in opposition to our wishes. For example, a dieter may exercise self-control to lose weight, drug abusers or alcoholics may finally break their addictions, and a moral individual may disobey an immoral order despite the consequences he knows he will face. Such examples seem to be unmistakable signs of freedom.

A strong defense of human freedom is offered by Viktor Frankl in his classic work Man’s Search for Meaning, in which he describes the variability of individual responses among his fellow inmates to the dehumanization of Nazi concentration camps; some responded like saints, some like monsters. Frankl was the founder of logotherapy, an influential school of thought in which the need for meaning supersedes the sexual and aggressive drives that Freud believed are our governing motivations.

However, the search for meaning is subject to the same cause and effect forces as the drives identified by Freud. Yes, it is true that we make choices and that individual human responses vary, even under extreme duress. But computer programs also compare options and choose between various conclusions according to their algorithms. Making decisions does not require the freedom to have made decisions other than the ones that were actually made. Even if Frankl was correct—and I believe he was right about the central importance of meaning in human life—we don’t decide to need meaning. The pursuit of meaning is an adaptive solution to certain problems faced by our ancestors; like every other part of us, it is a product of natural selection. Even this most human activity and the moral principles that can thwart other human impulses are not independent of the causal laws that govern all events in the universe.

Many years ago, I treated Lenny, a violent rapist whose last offense was committed at the age of 16. Tried as an adult, he was sentenced to 20 years. Then he was also committed to a prison treatment center for “one-day-to-life” as a “sexually dangerous person.” This meant that even after serving his sentence, he would remain in prison until clinicians judged that he was no longer a danger to others.

Lenny had “F U C K” artlessly tattooed across his fingers near the knuckles of his right hand, and “- Y O U” in the same place on his left hand (the clumsy hyphen ensured a character on each digit). The rest of his body was also covered in amateurish tattoos with which he and his buddies illicitly branded one another during their years in juvenile detention. All of his mother’s male siblings were serving long prison sentences for violent crimes, and Lenny grew up among motorcycle gangs. He was filled with shame and self-loathing for his ugly tattoos and the mess he had made of his life but was unable to change it.

During one therapy session, Lenny hauled back and punched himself on the side of his own cheekbone with such force that the loud crack of the impact startled me. On another occasion, he told me how he had placed a metal combination lock inside a sock so he could swing it like a mace. I asked him why he thought he was always so ready to commit violence. I pointed out that other men in prison—some of whom he admired for their toughness—were no longer getting disciplinary reports for violent interactions because they were exercising the self-control that we needed to see in order to recommend their release from their day-to-life commitments. He responded as if I were living in the hopelessly naïve world of an innocent child. His reputation for violence was necessary, he told me, if he was to survive in his world. This post hoc rationalization dodged the question I had asked. Lenny behaved as he did because it was who he was; he had no freedom to do otherwise.

In the concentration camp, Frankl experienced a world of far more extreme violence. Yet, he could see choices where Lenny saw none. But consider Frankl’s prior history. Logotherapy was surely influenced by his concentration camp experience, but it was not a response to it. Frankl came from a stable middle-class Jewish family with three children. (All the others except his sister perished in the Holocaust.) Prior to spending three years in four different concentration camps, Frankl had an established career as a psychiatrist who had been writing and publishing papers on logotherapy. Unlike Lenny, he came from a world in which moral meaning not violence could generate a stand against naked aggression. Frankl was fortunate to survive the camps. Lenny died during an escape attempt after falling from a second-story window.

What we learn and experience during our lifetimes greatly affects us. And as we know from looking at the regional religions of the world, the beliefs people hold sacred—beliefs for which, not infrequently, they will be prepared to sacrifice their very lives—tend to be what they were taught when they were little. It is no wonder that almost all of the violent men I treated in prison were victims of violent abuse and/or severe neglect when they were growing up. Not only had many of them inherited the genes of violent parents, but they were also born into violent environments. Harry Harlow’s experiments with rhesus monkeys who were cruelly separated from their mothers in infancy yielded emotionally stunted and socially inept adults.

These factors—natural selection, genetic disposition, innate motives and hungers, the cumulative effects of personal experience, current biochemical factors, unconscious brain activity, and the stimuli of the environment—all combine in complex ways to produce the experience of the moment and our consequent actions and reactions. There is no Daniel Kriegman who can act as a separate ego free from the physical laws governing cause and effect. There is just the undulation of what Einstein called the Unified Field, as it folds in on Itself and acts and reacts to Itself.

Guilt and responsibility

The jury in the Arthur Shawcross trial was unpersuaded by Lewis’s diagnosis of DID and duly convicted Shawcross of murder after just half-an-hour’s deliberation. He was sentenced to 250 years to life in prison, where he remained until he died of a cardiac arrest in 2008, aged 63. However, Lewis’s theories have attracted greater attention and support in the years since. Admittedly, multiple personalities are rarely seen outside of psychotherapy and clinical evaluations by clinicians who are convinced of the reality of DID. But that may simply be because they are extremely rare, or because most people with DID don’t come to the attention of the mental health or criminal justice systems.

In any event, the psychiatric consensus is now that some instances of DID are almost certainly real. Today, trauma-induced DID is included in the diagnostic bible of the American Psychiatric Association, and its existence is uncritically reported by numerous authoritative sources (Psychology Today, WebMD, NAMI, the American Psychiatric Association, the Mayo Clinic). Some researchers even believe they have evidence of a neuroanatomical basis for the disorder (but note that this research found publication in the European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, which is a journal run by a community of believers).

In contrast, we have the Fantasy Model (also called the sociocognitive model) which holds that DID is mediated by sociocultural factors and is found in individuals who exhibit a high level of suggestibility and fantasy proneness. Like Barber’s and Sarbin’s challenges of the altered-state model of hypnosis, this latter view maintains that there are no alternate personalities, and that the DID phenomenon is simply the co-creation of researchers and the highly suggestible, fantasy-prone individuals who go along with them. Avoidance of responsibility for heinous acts could accentuate this tendency, as Dietz and others have argued.

My own experiments with hypnosis and my professional experience as a clinician have persuaded me of the former view. Hypnosis showed me that about a third of perfectly sane, highly intelligent subjects were able to have sequestered experiences, which post-hypnotic suggestion made temporarily unavailable to consciousness. My work with psychotic individuals demonstrates that some patients unquestionably believe things despite clear, unequivocal evidence to the contrary; evidence that, at other times, they are fully able to acknowledge. Patients with a clear history of schizophrenia—a condition that even Barber, Sarbin, and Dietz would acknowledge—believe they are actually hearing voices telling them to do things and making claims about their status as a person.

Like hypnotic subjects who have no memory of their experiences while in a trance, some multiples are almost certainly unaware of other aspects of their experience as they manifest a particular personality. Are some of them faking such a condition in order to avoid punishment? Without question, some people act crazy in the hope that they can avoid the consequences of their actions. Nevertheless, despite ongoing controversy based on real problems with diagnostic biases, there is some basis for the now-conventional wisdom that some DID phenomena are real.

But if DID is real and an individual is temporarily under the control of a deviant personality, can they really be said to be in control of their actions? This is the wrong question because none of us is truly free. All actions and experiences are the inevitable culmination of forces and circumstances beyond our control, including (paradoxically) the belief and feeling that we are in control and acting freely. This does not, however, mean that nobody can be considered guilty. We hold people responsible for their actions precisely because we want to contribute to the forces that do control their behavior in order to affect their future actions, as well as establishing rules and consequences as a deterrence to influence the actions of others.

Our understanding of guilt should therefore be separated from the notion of free will and from degrees of mental health. Instead, it should be treated as a question of whether or not an action actually occurred. Instead of “not guilty by reason of insanity,” the conclusion in such cases should be “guilty and insane.” Punishment retains legitimate functions for those who acted in ways they knew were immoral and illegal: retribution for the victims, protecting the law-abiding from incorrigible criminality, and deterrence. But the dangerously insane person who doesn’t know that what they are doing is wrong should not be punished. They should be given a sentence that ensures that they are segregated from society and treated until they no longer pose a risk to others. Like the criminal, the length of a custodial sentence should be determined by the degree of harm caused and the risk of reoffending.

To illustrate the failure of the current system, consider the patient I treated at the State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. He was a genuinely personable individual. Unlike Lenny, while sane he harbored no scary ideas or impulses and he never embroiled himself in violent conflicts. In a psychotic state, however, he killed three people, two of whom were his friends. He had gone AWOL from the Navy in search of the Virgin Mary whose help he needed to prevent an apocalyptic alien invasion. When his MP colleagues caught up with him, they tried to place him under arrest. Had they succeeded in returning him to the base, he would simply have received a discharge and treatment for his psychosis. He believed, however, that they were taking him away to be executed, and a violent struggle ensued. He wrestled a gun away from one of them and killed them both, along with a bystander who happened upon the scene. Following his capture months later, he was found “not guilty by reason of insanity” and hospitalized.

Given the gravity of his violent conduct, he should have been found guilty but insane, sentenced to a loss of freedom for a long period of time, and only released after that period if the risk of psychotic violence was clearly diminished. But because he was not guilty of any crime, he had to be released two months later when his psychosis went into temporary remission. He wasn’t “an imminent threat to himself or others” due to psychosis, which is required if someone is to continue to be committed involuntarily to a mental institution. Not long afterwards in another psychotic state, he went off to find Mother Mary again. Speeding down a highway, he was stopped by a state trooper. When he lunged for the officer’s gun, the officer shot and wounded him. Three months later, recovered from his injury and with his psychosis in temporary remission again, he was re-released because he was “not guilty by reason of insanity.”

He was finally arrested after a relatively minor argument during which he slapped his mother. This time, he was sent to the state hospital where I treated him. This hospital specialized in treating extremely dangerous men and he was held under the assumption that his prior psychotic breaks indicated that he did, in fact, pose an imminent threat to others. After I left state employment, he remained in psychotherapy with another clinician for many years until the risk of violence due to psychosis appeared to be minimal. He was then released and decades passed without further incident. Given the uncertainty that attends any such risk assessment, one can debate whether he should ever have been released. But I am certain that he was suffering from the delusion that he was acting in self-defense when he shot his three victims. He simply had no other discernible reason to kill them; he wasn’t a “criminal” or even an angry man. When he was not in the grip of his psychotic delusions, he was an extremely congenial fellow. Really.

In my experience, the horrors committed by my most violent patients were matched only by the horrors they experienced in childhood—they were losers in the lotteries of genetics and/or circumstances that determined who and what they became. The compassion with which Dorothy Lewis treated the serial killers she came to know can coexist with revulsion for what they did. Whether or not Arthur Shawcross confabulated the existence of his alter-ego “Bessie” during his interviews with Lewis, the nature of the crimes he committed should be enough to convince most reasonable observers that he was a profoundly sick man—according to his own confessions, they involved not just rape and murder, but also compulsive pyromania, evisceration, necrophilia, and cannibalism.

The criminal justice system should not be trying to determine guilt and responsibility based on whether actions were committed “willfully”—that is, whether or not the actors were capable of “freely” deciding to act as they did. Rather, we should focus on our aims: punishment to change the behavior of corrigible criminals, retribution and justice for the aggrieved victims, general deterrence for others, and segregation of the dangerous from society for our protection. And, of course, for those who are clearly psychologically impaired and did not realize the wrongness of their actions, our focus should be on treatment.