Art and Culture

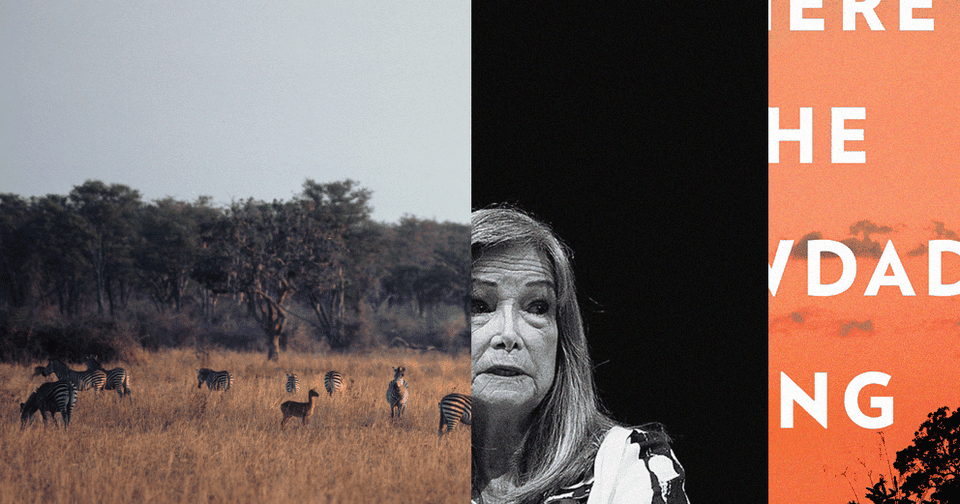

The Delia Demolition

Why is the Atlantic slinging mud at the 72-year-old author of ‘Where the Crawdads Sing’ on the eve of the film’s release?

Delia Owens’s 2018 novel, Where the Crawdads Sing, is among the most successful American pop fictions of the 21st century. It has sold roughly as many copies as John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (which has been in print for 83 years), Grace Metalious’s Peyton Place (66 years), Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (61 years), William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist (51 years), and Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (43 years). It has been on the New York Times fiction bestseller list for 167 weeks, where it currently sits in first place. It has sold roughly 12 million copies to date, but could well double that figure in time, which would put it somewhere in the vicinity of Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel Gone With the Wind and Daphne du Maurier’s 1939 novel Rebecca, two of the most storied titles in all of English-language popular fiction.

A film version of Where the Crawdads Sing was released on July 13th, and it is one of the few Hollywood blockbusters to be made almost exclusively by women. It was produced by Reese Witherspoon (an early promoter of the book) and her business partner Lauren Neustadter, adapted for the screen by Lucy Alibar, and directed by Olivia Newman. Newman has helmed only one previous feature film, the low-budget 2018 indie First Match, which was snapped up by Netflix after a single film festival screening. Newman’s follow-up stars English actress Daisy Edgar-Jones, who has been hovering on the edge of breakout stardom for two years now, since her memorable turn as Marianne Sheridan in the 2020 TV mini-series Normal People (based on a Sally Rooney novel). Here then is an occasion for liberals who fret about female under-representation in the arts to celebrate.

But not so fast. On July 11th, the editor-in-chief of the Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg, wrote an article informing those who were unaware (and reminding those who were) that Delia Owens is wanted for questioning by Zambian police investigating the fatal shooting of a suspected poacher in the mid-1990s. The murder took place in North Luangwa National Park, where Delia lived with her ex-husband Mark. Christopher Owens, Mark’s 25-year-old son from a previous marriage who resided in the US state of Maine, was staying with them at the time. The couple ran an elephant-conservation operation there called the North Luangwa Conservation Project, which they had established in 1986, and which was financed by a nonprofit organization they’d created called the Owens Foundation.

As it happens, an ABC News team were in Zambia at the time filming a profile of Mark and Delia Owens for a TV show called Turning Point. The profile, titled Deadly Game: The Mark and Delia Owens Story, was broadcast in the US on March 30th, 1996, and it included footage of a Zambian game scout shooting and killing a man. In the voice-over, Meredith Vieira, the Turning Point correspondent who fronted the segment, describes the unidentified victim as a “trespasser,” but the scout says he believed him to be an elephant poacher. His body has never been recovered.

The broadcast was well-received by American TV critics, but Zambian authorities were less pleased. Donors to the Owens Foundation were also unhappy. Mark and Delia Owens sent them a letter explaining that, “The ‘shoot to kill policy’ is only used by Zambian government Game Scouts in self defense. It is NOT a policy of our project. … We were not involved in the incident, or in any other incident of this nature.”

Another letter from the Foundation stated that, “ABC was looking for sensationalism. They insisted on going on patrol with the game scouts alone over and over but never said what they had encountered. We were just shocked. … From what we have been able to find out about the incident, the scouts felt so protective of the unarmed camera and sound people that they killed the poacher—who was, indeed, heavily armed and, according to Zambian law, subject to ‘shoot to kill.’” Goldberg pointed out that “there is no evidence in ‘Deadly Game’ that the alleged poacher was heavily armed, or armed at all, when he was shot, and it is by no means clear that Zambia tolerated the killing of poachers.”

The Owenses’ denials notwithstanding, Zambian law-enforcement authorities decided that they might have been involved in the incident. Mark and Delia both left the country in September of 1996. They said they were taking a brief vacation from Zambia but never returned.

In their absence, the American Embassy in Lusaka insisted that they are innocent of any crime, and revealed that Zambian officials had seized hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of Foundation equipment. This essentially ended a decade’s worth of elephant conservation activities by the organization and left dozens of local employees jobless. ABC News also defended the Owenses against accusations of wrongdoing. Janice Tomlin, the Turning Point producer who first approached Mark and Delia about participating in the segment, wrote to the American Embassy in Zambia and said this:

I have learned that the footage that was broadcast on our program of a poacher being killed has created a problem for the North Luangwa Conservation Project. I can assure you in the strongest way possible that neither Mark nor Delia Owens nor any other North Luangwa Conservation Project staff were even in the area at the time of this shooting.

And that seemed to be that.

Fourteen years later, in March 2010, the New Yorker ran an 18,000-word story on Mark and Delia Owens and the North Luangwa Conservation Project. It was written by Jeffrey Goldberg under the title “The Hunted,” and it portrayed the Owenses in a harshly negative light. Goldberg’s essay acknowledged that elephant poaching was indeed a huge problem in Zambia at the time of the shooting, and credited the Owenses with helping to restore the elephant population of North Luangwa National Park. “In 1960,” he wrote, “the park held about seventy thousand elephants; by the nineteen-eighties, the population had been hunted almost to elimination. The Owenses estimated that by the time they arrived, in 1986, there were only five thousand elephants in the park.” Goldberg quoted Alexandra Fuller, a friend of the Owenses and author of the acclaimed memoir Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, who told him that, by the 1970s and ’80s, “There were lorries coming out of the park with hundreds of tusks. All sorts of people were funding their wars using the ivory out of the park.”

Goldberg also acknowledged that Zambia suffered from government corruption and that its desultory efforts to combat the poaching were ineffective. The poorly paid scouts employed to protect the park were largely unsupervised and were understandably reluctant to confront poachers armed with AK-47 assault rifles. So, the government agreed to allow the Owenses to become “honorary game rangers,” which Mark seems to have believed placed him in charge of the scouts.

Mark considered the struggle against poaching to be a war, and as it unfolded in the legal and ethical gray zone of the Zambian wilderness, things began to get out of hand. Goldberg reported that Mark Owens directed the scouts to capture, torture, and even murder poachers. He described Owens training and leading what amounted to a paramilitary organization of scouts for this purpose, and we are told that the most productive recruits were rewarded with guns, knives, and other prizes. (Owens denies these allegations.)

Early in his African sojourn, Mark Owens learned how to fly a helicopter and a small airplane in order to scare off poachers from the air. Mark claimed that neither he nor anyone working for him ever fired a shot from either, but would frighten poachers away by hurling firecrackers at them. By all accounts, Mark’s battle with the poachers became an obsession that placed his marriage in jeopardy. Delia was adamantly opposed to his anti-poaching efforts, which she believed were endangering their lives, and she even separated from her husband for a while because she considered his behavior to be so reckless.

Mark was the primary villain of the piece, but his son Christopher also came in for a good deal of criticism. In fact, Goldberg discovered that it may well have been Christopher who murdered the poacher on camera:

There were three sets of gunshots in the killing shown in “Deadly Game.” The first shot, the one that knocked the alleged poacher down, was fired before the camera began rolling, according to Meredith Vieira’s narration. The second shot—the first to be heard in the video—came from a thin black man in a green uniform. The third came from offscreen, fired by an unidentified shooter. On my visits to the North Luangwa region, I had asked about the scout in the video, a man I eventually learned was named London Kawele, but I was told that he had been transferred to another part of Zambia, or that he was dead. The ABC documentary doesn’t indicate who fired the first and last sets of shots. In the absence of a witness’s testimony, there has been a persistent controversy about what actually happened on the video—who the other shooter was and, in some quarters, whether a killing happened at all.

[Mark] Owens gives his interpretation of the shooting in his letter to the Zambian attorney general: “I have no direct evidence of what I am about to suggest, however, based on what I have been told by others, I believe that the following may describe what actually happened: I believe that one or more game scouts, excited by being filmed for international television, shot a poacher in front of the camera.”

In the intervening years, supporters of the Owenses have put forth various other explanations. Mary Dykes [administrative director of the Owens Foundation and Delia Owens’s sister-in-law] told me that the scene might have been filmed in Zimbabwe; she also suggested that ABC News could have staged the shooting with actors. Gordon Streeb, the former U.S. Ambassador to Zambia, also said that this was possible. “My judgment is that they more likely staged something that was fake for visual effect, and no one was killed,” Streeb said, adding that ABC “could have been in Zimbabwe.” Streeb said he found the film suspicious because “when you hear the gunshot go off, the body twitches, but you don’t see blood spattering. Beyond that gunshot, there’s no evidence.”

But Chris Everson, the ABC cameraman who shot the footage, provided Goldberg with a different account of the killing:

According to Chris Everson, though, the documentary did not present the whole truth. I reached him early this year at the winery he owns with his wife in the Cape Province of South Africa. (Everson still works as a cameraman, mainly for “60 Minutes.”) For the first time, he spoke of what he saw. It was not the Zambian scout, he told me, who fired the first shot or the last shots: it was Christopher Owens, Mark Owens’s son.

“It’s a very complicated story, it was a very emotional thing, it was a very bad thing,” Everson said. “It’s something that never should have happened.” Christopher Owens, who was twenty-five years old at the time of the incident, was spending the summer with his father and stepmother at Marula-Puku. On the day of the shooting, Everson said, Mark Owens flew him, along with Christopher and the scout, London Kawele, to a remote location within the park. It was an unusual group; scouts rarely went on patrol without at least three other scouts.

According to Everson, Mark Owens left the three men in the park and returned to his headquarters. They quickly came across an abandoned camp and waited in ambush. When a suspected poacher entered the camp, Christopher Owens opened fire. “I don’t know what was going on in Chris’s mind,” Everson said. “He had a rush of blood to the head. I don’t know why he shot him in the first place. I don’t.”

Everson began filming after Christopher fired the first shot, the one that felled the man Meredith Vieira described as a “trespasser.” Then the scout fired at the man, who was now on the ground; this is the first shot heard in “Deadly Game.” Everson said he continued filming as Christopher, who was standing off camera, fired the three final shots at the man’s body. “I should never have allowed it to happen,” Everson said.

I asked if he had considered alerting the police in Lusaka that he had witnessed a killing by an American visitor to Zambia. He said, “That was way above my pay scale. I was working for ABC. It wasn’t my business to do that.” Everson would not say how he got back to camp after the shooting, but he said that he did not see Christopher Owens again.

This account appeared to be supported by Deborah Amos, the on-camera ABC reporter originally assigned to the story. Amos told Goldberg that Andrew Tkach, the segment’s field producer, had later informed her that “Mark’s son had killed somebody.” One theory floated by people who have studied the crime is that after Christopher Owens committed the murder, Mark took the body up in his helicopter and dropped it into a lagoon, where it would have quickly been consumed by crocodiles and other animals.

Christopher Owens is a martial artist and several of the game scouts who worked for the Owenses have said that he would sometimes beat them while training them. Unlike Mark, he was not an “honorary game ranger,” he was simply an American on vacation. And when he returned home to Maine, his behavior became violently erratic:

Christopher Owens has led a tumultuous life since he left Zambia. He has been arrested numerous times, and in 2001 he was convicted for misdemeanor assault after attacking a man in a Portland bar. He has since pled guilty to misdemeanor charges of assault and terrorizing. … In December, 2003, Christopher was living in the town of Palmyra. According to a neighbor, Christopher Silva, Owens was hunting in the woods near his home when he shot and killed one of Silva’s dogs and injured another. “One of the dogs came out of the woods with one of his legs missing, and so I ran out and looked for the other one,” Silva told me. “I found the body hidden under some leaves.” The police searched Owens’s house soon after, and found a rifle with a scope attached. In a statement for the police, Owens wrote that he believed the dogs were actually coyotes.

In his New Yorker essay, Goldberg built a pretty compelling case against both Mark and Christopher Owens. But he didn’t implicate Delia in any wrongdoing, and she cuts an anxious and frightened figure, appearing only to express her worry and disapproval or to defend her husband and stepson. She vehemently denied any knowledge of the shooting and Goldberg presented no evidence to the contrary. Towards the end of the essay, he paid an unannounced visit to the couple’s ranch home in Idaho after he failed to secure their agreement to sit for an interview:

One day this winter, I made a visit to their ranch. The Owenses had long declined to speak with me. It was snowing when I arrived, and the clouds had settled on the slopes of the mountains behind their log cabin. As I pulled up their drive, I saw Delia Owens emerging from a barn on the property. She was feeding hay to a herd of deer that had gathered near their cabin.

Delia became agitated when I introduced myself. “I’m going to have a stroke right now. I’m going to have a heart attack,” she said. “How in the hell did you find us?” She composed herself, and asked me what I wanted to know, and I told her I hoped to talk about the ABC video. “By the time they came, the poaching was over,” she said. “They were waiting for some action. We told them poaching was over. They just wanted something sensational.”

I asked Delia about the accusations that her stepson had shot the man in North Luangwa. “Chris wasn’t there,” she said. “We don’t even know where that event took place. It was horrible, a person being shot like that. We think people say Chris did this because they got confused, because the cameraman was named Chris, too,” she said. “We don’t know anything about that trip.” (Donald Zachary [an attorney for the Owenses] later wrote to me that Christopher Owens denied being involved in the shooting.) I told her that I had heard frequently in the valley that Mark carried poachers in the cargo net underneath his helicopter. She laughed and said that the people around the park were confused because Mark once gave Christopher a ride in the cargo net. “I know how the rumors about dropping poachers in the river got started. Mark put Chris in a harness under the helicopter and gave him a tour of the valley. Imagine that view! I was going to do it, but I got too scared. So people saw Chris in the harness and they assumed it was a poacher.”

I asked Delia if her husband was available to speak to me. She waved to the mountains behind us and said, “He’s up there.” She added, “He’s going to be very angry you’re trespassing.” She said that she and her husband would not allow me to talk to Chris Owens, who now lives in Maine. “He might say something that you could misinterpret,” she said. “He’s trying to get his life together. Just leave him alone. You have something to ask him, ask us.” She told me, “Chris came in the summers to help out. He was involved with the scouts. He was involved in their training in various aspects.” She would not elaborate further.

As we talked, Delia again grew upset, and she walked off toward the deer, who were feeding a few yards away. She pointed out a doe to me. “This one is named High Cheeks,” she said. The snow was coming down harder, and she looked back at the mountains. She told me Mark would be back soon. “He’s going to be upset that you came onto the property.”

She said that she and Mark had no knowledge of poachers being killed. “We don’t know anything about it,” she said. “The only thing Mark ever did was throw firecrackers out of his plane, but just to scare poachers, not to hurt anyone.”

Goldberg didn’t hang around to talk to Mark, but his essay made it clear that he believed Mark and Christopher were both involved in the killing of the poacher on Deadly Game. If Goldberg uncovered any evidence that Delia was involved, he didn’t report it.

Goldberg’s New Yorker essay may have been profoundly unflattering to the Owenses, but it was an outstanding piece of journalism—thoughtful, measured, deeply researched and reported, and carefully balanced in its weighing of conflicting testimony. His new Atlantic article is none of those things. It is titled “Where the Crawdads Sing Author Wanted for Questioning in Murder” and, unlike its epic predecessor, it runs to only about 2,500 words, during which Goldberg rehashes the more lurid highlights of his New Yorker essay.

The intervening success of Where the Crawdads Sing, and the publicity surrounding the new movie, however, have encouraged Goldberg to give her prominence that her actual involvement—at least, according to his own detailed version of events in 2010—doesn’t deserve. In his Atlantic article, Goldberg writes:

Zambian authorities today remain interested in bringing charges for the 1995 televised killing. On a visit last month to Lusaka, Zambia’s capital, I spoke with several officials who expressed both displeasure and wry amusement about Delia Owens’s recent publishing and cinematic success. The country’s director of public prosecutions, Lillian Shawa-Siyuni, confirmed what officials at the Criminal Investigation Department of the Zambian national police told me: Mark, Delia, and Christopher Owens are still wanted for questioning related to the killing of the alleged poacher, as well as other possible criminal activities in North Luangwa. “There is no statute of limitations on murder in Zambia,” Siyuni said. “They are all wanted for questioning in this case, including Delia Owens.”

Delia’s novel is of dubious relevance, but Goldberg has a go at linking the book and the crime anyway. It tells the story of a young girl named Kya, abandoned by her family at her home in the marshlands of North Carolina where she grew up. Towards the end of the novel, Kya is arrested for the murder of her abusive former lover—a crime of which she is acquitted but that we subsequently learn she did in fact commit. Drawing for support on a 2019 review in Slate by Laura Miller, Goldberg invites us to infer that because the book’s protagonist is heavily autobiographical, the murder she commits may amount to a stealth confession on the part of the author. “A televised 1990s killing in Zambia,” announces the article’s subhead, “has striking similarities to Delia Owens’s best-selling book turned movie.” Not only does this strained analysis misunderstand how writers of fiction routinely mix experience and imagination, but it also implies that Delia Owens is directly implicated in the murder itself. Not even the Zambian authorities believe that—she is of interest, they say, only as “a possible witness, co-conspirator, and accessory to felony crimes.” [Emphasis added.]

The present climate of race consciousness in liberal journalistic circles also seems to have moved Goldberg to emphasize an aspect of the story to which he gave only passing attention in 2010. “The Owenses’ writings,” he reported then, “on occasion convey archaic ideas about Africans,” and he devoted about 800 words of his 18,000-word essay to examples. Much of that section is reproduced in his Atlantic article, but it now fills the final four paragraphs, leaving the reader with a clear imputation of racism and the Owenses’ story is now compared to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Goldberg accuses them of “frequently describ[ing] adult Africans in childlike terms,” and Delia Owens's novel is likewise “filled with improbable and condescending portraits of Black people,” which we are told, “is of a piece with the Owenses’ apparent attitude toward Africans, as evidenced by eyewitnesses and even a cursory reading of their own writing.”

Absent is the more sympathetic account of the Owenses’ behavior and motives offered by Turning Point reporter Meredith Vieira in the New Yorker essay: “My memory of them was that they saw themselves as saviors of these animals. They were highly emotional about it. The level of caring was very deep, but a corruption of values could come with that. They were adamant about saving these elephants.” But Goldberg seems to have revised his assessment of the ABC crew as well, disparaging their segment as “in many ways a typical white-savior story, an emotion-saturated tale of two telegenic Americans on a mission to save elephants from poachers and corrupt African officials.”

Curiously, the ABC News journalists and technicians involved in making the documentary have refused to cooperate with Zambian investigators or surrender their footage. The faces of the scout and a second figure carrying a rifle were obscured in the broadcast to make them unidentifiable (apparently the upshot of a confidentiality agreement the reporters signed as a condition of being allowed to accompany scout patrols). But ABC’s raw footage would no doubt help to answer some of the questions Zambian officials have about the incident. Goldberg reprints part of an interview he conducted with Biemba Musole, the Zambian police detective leading the investigation, during his research for the New Yorker essay. “The ABC News show is an accessory to murder, either after the fact or during the committing of this murder,” Musole said. “The cameraman and reporter are accomplices to this. The docket is still open on this case. Why won’t the cameraman come in and tell us what he saw and show us his film?”

Interesting, but not news. This quote, like all the other information about the murder in Goldberg’s Atlantic article, is now 12 years old. His Atlantic story includes no new revelations about the case, because there are none. The scout is still missing and possibly dead. The victim’s remains have not been recovered and his identity is still unknown. And ABC is still refusing to make its raw footage available to either Goldberg or to Zambian officials, so the journalistic and criminal investigations are no further forward than they were when Goldberg’s New Yorker essay appeared 12 years ago. The only apparent reason for raking all this up again is to cast a pall of scandal and suspicion over the new film and the author of the publishing sensation on which it is based.

As Goldberg originally reported, Delia was a vehement opponent of her husband’s vigilantism (a point he neglects to repeat in his new piece) and a peripheral figure in the story of the shooting itself. We do not know what—if anything—she knew about the crime, and it is plausible that, given the couple’s volcanic quarrels about his use of violence, he kept her in the dark (if indeed he knew anything about it at all). Today, her connection to the events at issue is even more remote than it was at the time. She and Mark are reportedly divorced, which means she is no longer related to Mark or Christopher either by blood or marriage. Christopher was raised by his birth mother. Whatever his personal problems may be, it seems unfair to use them to cast aspersions on his stepmother, who provided neither his genes nor his upbringing.

The US and Zambia have no extradition treaty, so Zambia can’t compel US authorities to hand over the Owenses for interrogation or trial. But what does Goldberg think will happen to Delia Owens should she return to Zambia to assist with the inquiry? As he mentioned in his 2010 essay (but fails to recap in his Atlantic article), American citizens have good reasons to be wary of entangling themselves in the Zambian legal system:

The American Embassy warned the Owenses not to enter Zambia until the controversy was resolved. In a consular memorandum of December 3, 1996, an official wrote that the Owenses “had better have ironclad assurances that they have been exonerated and that all arrangements are in place for their uneventful return before they consider such a move.” [US Ambassador to Zambia, Roland] Kuchel told me that Zambia’s justice system was thoroughly corrupt, and he feared that if Mark Owens were held in a Zambian jail, he would be raped and infected with H.I.V.

The impression left by Goldberg’s Atlantic article is that, while the details of the murder may be opaque, the Owenses are nonetheless clueless neo-colonialist snobs who went where they didn’t belong and threw their weight around, so they should return and face the vagaries of the Zambian justice system, no matter how unpleasant that experience turns out to be.

Failing that, the Atlantic has done what it can to embarrass Delia Owens and to damage Olivia Newman’s new film on the eve of its release. The timing of Goldberg’s otherwise redundant article looks like an act of sabotage, intended to disgrace Owens with insinuation and innuendo in the absence of any good evidence that she did anything wrong. Things being the way they are now, the filmmakers and young cast will no doubt be held accountable for the stigma with which Goldberg’s article has tainted her novel, and invited to distance themselves from its author.

What’s most strange about all this is that nobody who has followed this story—not even, I suspect, Jeffrey Goldberg—seriously believes that Delia Owens had anything to do with the crime ostensibly at its center. Perhaps the attempt to blacken her big moment is simply evidence of that perverse human impulse known as “tall poppy syndrome,” defined by Wikipedia as “a cultural phenomenon in which people hold back, criticise, or sabotage those who have or are believed to have achieved notable success in one or more aspects of life, particularly intellectual or cultural wealth.” According to this reading, Delia Owens’s real crime is not murder or even racism, it’s that she wrote the most fantastically popular novel of modern times.