Abortion

An Australian Perspective on Abortion

The closest example of a counterfactual to Roe v. Wade is Australia, where there is a federal system with no unifying law or ruling concerning abortion.

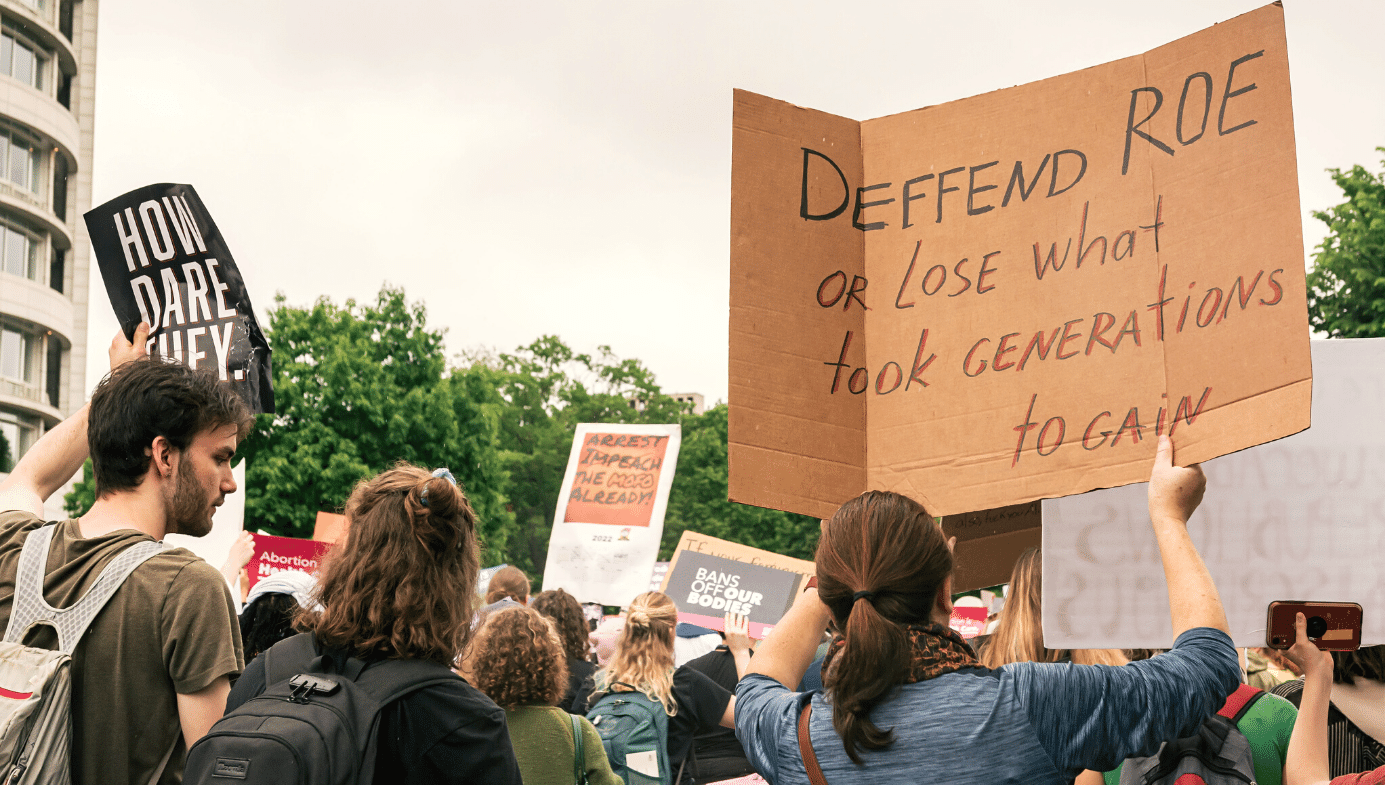

In the aftermath of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, it would be beneficial for all Americans, regardless of whether they are cracking the champagne or drowning their sorrows in gin, to consider what will come next.

The closest example of a counterfactual to Roe v. Wade is Australia, where there is a federal system with no unifying law or ruling concerning abortion.

In Australia, abortion has always been a matter for state parliaments—the legislative arm of government. Thus, each state has had different laws regarding abortion, and this is not such a terrible thing. Leaving morally complex questions, such as abortion, to each state has been a blessing.

Regardless of one's views on abortion, the Roe v. Wade decision was always understood to be in a precarious position and vulnerable to overturning if judges with more fealty to the text of the US Constitution (as written) than to precedent (how it has been interpreted) were appointed to the Supreme Court.

This has created the toxic division in America that preceded today's complaints about hyper-polarisation. The Roe decision had the opposite effect to the one intended. It didn’t put the abortion question to bed but made it an issue that has motivated the extremes and politicised the Supreme Court. I would even argue that it created the false binary of “pro-choice” and “pro-life.”

I reject the “pro-choice” and “pro-life” labels, as, even in America, polls show that most people’s views sit somewhere on a continuum between the rights of the (potential) baby and the rights of the (potential) mother. The staunchest defenders of the rights of the unborn agree that abortion is necessary when the mother is at risk, and, even amongst die-hard campaigners for women’s choice, there are very few willing to defend very late-term abortion on demand (or partial-birth abortion, as it is known).

That these slogans are framed as being for something is an indication that both sides want to protect something. Both slogans are half-truths. Abortion is a serious moral issue and anyone who wants to pretend otherwise has not thought deeply about it. The overturning of Roe is an opportunity to simmer down a bit and actually engage with the question of abortion in a far more reasonable way than the fever pitch at which the US debate currently rages.

One can only hope.

Slow and steady change

One of the statements that shocked Joe Rogan in his recent debate with Australian radio host Josh Szeps was that New South Wales (the state in Australia where both Szeps and I live) only removed abortion from the criminal code in 2019.

That didn’t mean that abortions didn’t happen. Doctors could perform abortions if the applicants fit into several broad categories where exemptions applied. These exemptions from the general prohibition on abortion covered most reasons why a woman might not have the physical, mental, or material ability to bring the pregnancy to term. What the law criminalised were abortions not performed in a medical setting and for the proper reasons. This law was as much about removing women from “backyard abortionists” and coercion as it was about regulating abortion so that a balancing of rights and interests could occur.

This is something lost in the US debate, where a false binary, yet again, is presented of abortion being “legal-or-not” rather than “legal-depending-on-the circumstances.” Polling shows this is how a significant majority of the population thinks it ought to be.

New South Wales now allows abortion on demand for up to 22 weeks. This is fairly standard across Australia, where the most restrictive states limit on-demand abortions to before 14 weeks and the most liberal limit it to 24 weeks. Even Victoria, the state with the most left-wing government and most relaxed laws around abortion (the “California” of Australia, if you will) restricts late-term abortions to medical emergencies only.

Coincidently, Victoria was the first state to legalise abortions after a landmark ruling called the Menhennit Case, the story of which was made famous by the film Dangerous Remedy, but, unlike the Roe decision, this case was based on state law and so only applied in Victoria.

Removing abortion from the criminal law and implementing on-demand abortion is a phenomenon that began in the 2000s. It was mostly driven by women unwittingly falling foul of the laws that limit legal abortions to those performed by a doctor, for example, by ordering abortion pills online.

For the most part, however, the story of abortion in Australia is one of slow change on a state-by-state basis as both attitudes and technology progress.

But slow change is no bad thing. It is far more stable and sensible than changing the legal landscape from one day to the next, which is what a top-down decision does. Those reeling from the Dobbs decision are probably experiencing what those who opposed unrestricted abortion felt in 1973 when the Roe decision was handed down.

Not having to deal with a Roe-like decision has been an advantage in Australia. It has meant that those wishing to change the law have needed to make the case for it in terms with which most people would agree. The views of social conservatives must be considered to be successful with the electorate. The parliamentary process discourages changes that are too quick and don’t bring the public along with them.

Allowing no great leaps forward also means that there is a limited risk of going back too far. If those wanting to restrict access to abortion were to submit a bill tomorrow, the proposal would be subject to scrutiny and would probably change the law only very slightly.

This is the way it should be when it comes to an issue like abortion, where both sides have an insight or something of value that they are campaigning for. Only legislation with the requirement to engage in debates and amendments can properly reflect a balancing between these positions.

Uncertainty

On my first day as in-house legal counsel for a medical company, a large folder landed on my desk. We were being sued for wrongful birth. If there is one thing all lawyers want to do when such a folder is given to them, it is to settle out of court. There is extremely limited precedent in Australia for these types of cases, so they could go either way. No matter what the court’s decision is, the name of the company or individual you represent is going to end up in law students’ textbooks.

For those readers who are non-lawyers, a wrongful birth case is a tort case brought by a complainant arguing that if it wasn’t for a party’s negligence, a child would not have been born. In cases where the negligence occurred pre-conception (e.g., a botched sterilisation procedure), claimants have been successful. But there has never been a successful case where the argument was that, had the third party not been negligent post-conception (often the sonographer or obstetrician), the person making the claim would have had an abortion and, therefore, the child would never have been born.

Aside from this being, historically, an area in which judges have not wanted to intervene (at least in Australia), one of the reasons these types of cases have tended to be unsuccessful is that there is no way to guarantee that the mother would have gotten an abortion. There is too much uncertainty.

It rhymes with another very morally complex issue, euthanasia, for which, no matter what one's leanings are during life, when it comes down to it, the choice is never truly ours alone in the end. I have known of an atheist with Parkinson’s disease who had said he wanted to end it before the disease progressed dying a natural death in the end, and a devout Catholic with lung cancer deprived of proper palliative care taking every pill in the house rather than suffering on. It is only when faced with the precise circumstances of their death that people really know what they will do.

This is also true when it comes to extinguishing life in utero. Both sides of the abortion debate seem naive as to how much autonomy—the very thing that both sides of the argument rest their case on—can be limited when life gets messy.

This is why abortion can never be black and white. It will, at least for the conceivable future, be bad—but the least bad option—for some women whose circumstances are sufficiently terrible, and it will also always be an egregious wrong when women who wanted the child are forced by circumstances to end the pregnancy.

There are uncomfortable truths that both the “pro-choice” and “pro-life” positions seem determined not to grapple with, but the only good abortion laws are the ones that rely on full truths, not half-truths. The only worthwhile debate starts with recognition of the wisdom of one's opponent.

Uncomfortable truths

Sex and responsibility

The pill and the availability of abortions revolutionised relations between the sexes but not in a wholly good way. A famous 1996 paper co-authored by Janet Yellen theorised that single motherhood skyrocketed in the 1970s in part because of the “technology shock” of the pill and legalised abortion, which made “shotgun” marriages less common. Logically, more bodily autonomy should have decreased the instance of fatherless children, but with more choice came more responsibility. If a sexual encounter left a woman with a child, it was now her fault; she should have been on the pill and, if that failed, got an abortion.

In previous decades, there was an understanding that the male partner played an important role in the creation of a baby and if a baby were to arise from a relationship, then he was encouraged to marry the woman in question. Today, we think of shotgun marriages as backward, but they were at least an admission that there was joint responsibility for accidental pregnancies, the burden of which should not rest solely on the woman.

Increasing responsibility for women is a difficult truth to acknowledge for the side often campaigning for liberalising abortion. Increased choice for women means taking more responsibility. The increased responsibility of women has, in turn, given men licence to abandon any accidental children they may father and, worse, insist that they needn’t take responsibility for contraception at all. An example of this would be the rise of “stealthing” (removing a condom in the middle of sex without the woman knowing or consenting).

As with every freedom, with sexual freedom comes responsibility for the consequences. This is something that social conservatives on the side of limiting abortion seem to recognise, however blinkered their view might be in some other respects. It is just ironic that the side that sells itself as pro-women has ended up in the position of excusing men from any responsibility for sex and reproduction, however unintended this endpoint was.

The limits of responsibility

Those that argue for fewer limits on abortion access might be blind to the problem that more choice invariably means more responsibility, but those that want to restrict abortion have not come up with another way of solving the problem that abortion—however terrible this solution might be—addresses: that of diminished responsibility. What is society to do with people who are not responsible or won’t take responsibility for their actions?

The most extreme example of lack of agency over the creation of life is the instance of rape, but at the lower end, there is the problem of the exact effectiveness of contraception.

The pill and condoms, we are told, are 99 percent and 70 percent effective, respectively, when used correctly and completely, as per instructions. But people who use contraception “in the wild” and not in perfect as-per-instructions conditions know that “shit happens” no matter how careful one intends to be. Condoms break (particularly when kept in the wallet for a long time), and taking pills is at the mercy of very fallible memory.

Then there are also people who, let's be frank, may have the capacity to consent to sex but should not be parents. Whether diminished capacity is brought on by mental illness, drug addiction, or material circumstances like homelessness, there are many people in society for whom it would be cruel (both to them and the children) to force them to be parents.

I often have disagreements with social conservatives who think that what to do instead of abortion is a second-order issue, but, ultimately, abortion solves a problem—however imperfect a solution it may be.

Without a solution to the problem that people who ought not to have kids end up producing children, there is not going to be an end to abortion.

It is out of character for social conservatives to be idealists, but when it comes to abortion, they expect people to be superhuman, not the fallible creatures that we are.

The key piece of wisdom from those who argue for abortion is that life is messy, and, however ugly terminating a pregnancy may be, it can be the least bad option.

The limits of choice

Both sides fail to recognise that women may be pressured to have an abortion by the lack of available alternatives.

I hold the view that it is a life at conception and, as such, I could not and would not have an abortion. I would personally like to have the choice, should I find myself accidentally pregnant—I have had some scares in my life—to adopt the child out. However, that choice has been completely removed.

In New South Wales, the progressive liberalisation of abortion has been paired with increasingly stringent adoption regulations, making having the child and putting it up for adoption (like in the cult film Juno) an option unavailable to women like me.

Australia, for historical reasons, is extremely squeamish about removing children from their biological parents. But the effect of this is that a woman who doesn’t want to have an abortion is left having to keep the child or go overseas to seek adoptive parents.

Likewise, women with limited social support such as from extended families who can take care of the children are also left without much choice if the father doesn’t want anything to do with the baby.

Having an abortion might be a choice, but circumstances can force a woman who does not want to have an abortion into having one. Many of these circumstances are things that progressives themselves argue for, be they limits on removing children or dismantling the extended family which can support a woman when the father is absent.

On the anti-abortion side, socially conservative attitudes are often paired with economically conservative views about the welfare state. However, the far more restrictive laws around abortion in Europe (that many in the US are fond of pointing to as a “gotcha” to progressives who insist that they are living in a backward country) are often paired with pro-natalist economic policies. Many years of fertility rates being below replacement level have led European governments to throw money at any woman who wants to have children. By helping to remove the material barrier to having children, more women choose to keep the baby when they find themselves accidentally pregnant.

The great untruth that both sides argue is that pregnancy is a choice for the mother as an individual, but legal, social, and economic factors, more often than not, dictate the “choice” that is made.

A warning

Australia can be not just an example but also a warning on complacency.

The lack of a top-down decision on abortion and the subsequent slow progress has meant that, far from being a deeply polarised issue, most Australians (for better or worse) would not be able to tell you what the abortion laws are in their state. This, in my opinion, is too much apathy for what is a serious moral issue but is far better than the intense polarisation that came as a result of Roe v. Wade.

Ultimately, the way forward from the Dobbs decision will probably leave everyone disappointed. The laws in some states will be too restrictive for half the population, and they will be too liberal in some states for the other half. But that is a good thing. Needing to compromise means that both sides of this false dichotomy will need to engage in good faith with the arguments of the opposition.

This is one of the easiest issues where, at least, if one doesn’t have ideological blinkers on, it is clear that both sides of the debate have their merits. The US has an opportunity to think deeply about abortion and not in half-truths and slogans.