Underneath the Sun

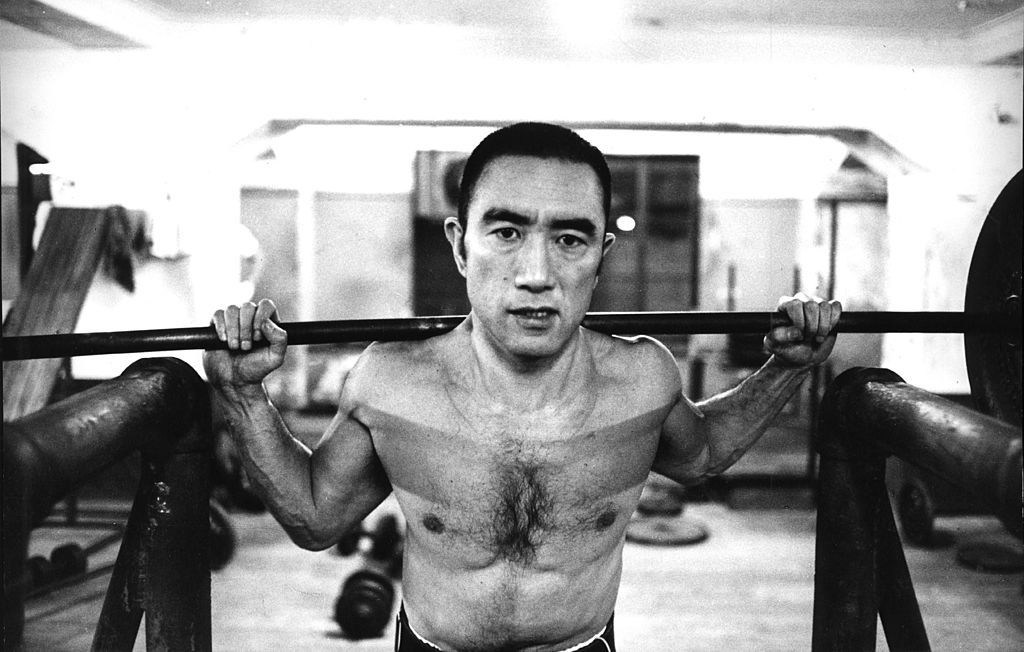

Written 70 years ago, Sun and Steel is Mishima’s hero narrative from frail, cave-dwelling, intellectual into a master of his own body.

“He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glances.” So wrote James Joyce of Mr Duffy, a reclusive character deeply ingrained in his routine and lonesomeness. A short story that was part of a larger collection of vignettes on Ireland’s urban middle classes, The Dubliners presents Mr Duffy as an individual who craves not only ideas but also an ennobling company with which to foster them. In many ways, Mr Duffy is the perfect representation of what my final year as a doctoral candidate felt like. I can remember writing my précis and a committee member’s telling me that if I didn’t look out for my health, I was going to wreak havoc on my body. Most of the advice was ignored until about month three when I realized just how much sitting (and smoking) I was doing.

One of the less remarkable features of dissertation writing is the sheer amount of sitting one does. For the first few weeks of writing, I became noticeably more sensitive to where and how I would position myself at a library or café, constantly shifting from one side to the other, or cracking my knuckles. These small tics were almost ceremonial at first, a way of inaugurating what would become an all-day event typing away at my laptop. But gradually, the movements became increasingly less voluntary, and what initially felt like ritual soon sank into distraction.

Was it nerves, an expression of anxiety at having to commit myself to a life like Mr Duffy’s? I realized that my nerves were beginning to surface interstitially through my joints and the other parts of my body that allowed for movement. One night, I caught myself staring blankly at my computer screen as my foot tapped piston-like under the desk. I abruptly stood up and walked away.

I went over to the bathroom and threw some water on my face. As I reached for a hand towel, I looked at myself in the mirror. Staring back at me was a man I barely recognized, a sort of graduate-school version of John Walker Lindh, sans the blindfold. Months had gone by since I had had an actual conversation with a friend or a colleague from my university. My current movement patterns were becoming increasingly restricted to the bare, mundane essentials of grocery shopping, getting coffee, and occasionally filling my car with gas. I no longer went into Manhattan to attend lectures or casually grab a drink with friends. The more parochial my routine became, the more irascible I grew when seemingly minor inconveniences interrupted my established flow. My body suffered along with my shrinking geography, and its softness and pallid appearance became the subject of concern for those closest to me. In short, I was feral, but not in the way that escaped pet rabbits grow sharper, longer teeth as a way of surviving an unpredictable environment. It was more in the manner of becoming less social, less aware of my circumstance that had grown fallow from a prolonged absence of care for my body. The unsettling sensations which leaked like energy out of my hands, feet, and neck forced me to reckon with the idea that I was dealing with an unfamiliar language, a vocabulary I did not understand.

Something about being in one's 30s has resulted in our culture long considering it to be a watershed period in a person's life. Jesus Christ is crucified and dies at the age of 33. Carl Jung, the Austrian psychoanalyst, once mused that adulthood begins at 35. Yet another wrinkle of insight was given to me by a friend, an arts journalist in New York, who had become a weightlifter. He noted that there is a kind of unspoken rule that after the age of 30, we’re obliged to decline into decrepitude. At that time, I had already realized that, perhaps, our very corporeal existence merited a more distinguished honor than being a receptacle for food and drink—as well as an exit for the same.

Whenever I expressed my thoughts to my academic colleagues on the importance of physically developing one’s body, I was surprised by their range of reactions, most of which seemed entirely negative. They fluctuated from passive disinterest to more caustic postulations that revolved around the idea of embrittled masculinity. Finding little intellectual recourse there, I did what many do today, and scoured the Internet to learn more about this newfound interest in bodybuilding. It was not just fact-finding, but also a hunt for other kindred spirits who perchance enjoyed philosophizing about their hobbies. Yet while the positive, almost saccharine attitude of bodybuilding athletes struck me as refreshing, if not clichéd, I began to miss the rigor of debate and challenging ideas, something which few in bodybuilding were as interested in as I was. At the same time, no one in my immediate social circle had an interest in seriously working out. Certainly, there was the odd yoga practitioner or the one guy who loved to run marathons, but no one who saw their body in the way I wanted to see mine—muscular, worthy of art. This I found strange, in that it seemed as though academia was going through something of a seasonal obsession with talking about the body in every way but strengthening it.

It wasn’t long until a friend in my department reached out to tell me how happy he was that I was getting into lifting, and he passed along a copy of the late Japanese author and Samurai enthusiast Yukio Mishima’s Sun and Steel. Whether it was the prose or his way of expressing wrenching thoughts that were on the periphery of what I could not yet adequately express, Mishima articulated a philosophical treatise on bodybuilding so eloquently that it was shocking to find out that so few in academia had explored its implications. In a way, I had found a document that underscored the importance of the body – a document that endowed improvement of the body with an almost Platonic quality by seeing its development as a journey into self-knowledge.

Written 70 years ago, Sun and Steel is Mishima’s hero narrative from frail, cave-dwelling, intellectual into a master of his own body. Practicing traditional Japanese martial arts as well as lifting weights—what he called “the steel”—he captured his insights of self-discovery in the phrase “learning the language of the flesh.” His memoir reads more like a theory of bodybuilding without ever calling it such. But, in truth, he went beyond the idea that developing one’s physique was simply a matter of art or even a sport. As a writer, he saw lifting as a way of giving his body its own kind of voice. Friedrich Nietzsche, in Thus Spake Zarathustra, approximates this idea of the body’s voice when he discusses the use of the first-person pronoun, “I”: “You say ‘I’ and you are proud of this word. But greater than this—although you would not believe in it—is your body and its intelligence, which does not say ‘I’ but performs ‘I.’”

Like Mr Duffy, I, too, had previously found myself referring to my body as if it were a completely separate entity. Mishima’s performative “I” spoke more to Nietzsche’s conception, a sense of bodily experience that spoke of activity, distinguishing it from how we are accustomed to understanding ourselves through poetry or literature. Mishima was all too well acquainted with this latter mode of intellectual discovery. For him, building the body was essentially bound up with answering the physical part of life’s chief existential question—who am I? He wanted to see this new kind of language quite apart from, and even in opposition to, the language of which we speak: the language of the mind.

“Mishima” was the pen name of one of Japan’s most prolific and infamous post-war writers, Kimitake Hiraoka. He wrote dozens of novels, poems, and plays and produced a short film. He was a man who, by and large, felt estranged from Japanese society under modernity. As a teenager, Mishima had witnessed the aggressive expansion of Japan across East Asia, as well as its crushing defeat by the United States. This defeat, however, was not just military but also cultural for Mishima—he loathed the onset of industrial mass consumerism, which he viewed as an acid eating away at the nation’s aristocratic values that he so treasured.

He became a devotee of the arcane and saw in the pre-modern practices of the Samurai a kind of holism that placed the mind on equal terms with the body. Mishima craved a life of honor, one that was ultimately driven towards death. After failing to seize a military compound in 1970, he committed ritual Japanese suicide (seppuku) before an audience of soldiers and civilians. Rife within Japanese literature is the notion of the romantic death—where a Samurai warrior exhausts every last fiber of his being to slay the enemy as he goes down in the fight. The very act of disembowelment by katana was Mishima’s way of saluting the Samurai culture he so desperately wished to be a part of and, moreover, a way to shock Japanese liberal onlookers.

At a certain point in his life, Mishima began to question the culture of the intellectual, the sort of dark, brooding types who stay up late burning the midnight oil, saturated in their emotions, and neglectful of their bodies. He wanted to seek out the sun and become like the men who marched under it with discipline and determination. He wanted to bask in it, to show off his muscles, and it would be through the steel—“the iron,” in the parlance of gym-goers—that Mishima would begin to transform his body. For him, the steel was the first step in learning who he was. As he noted:

The steel … gave me an utterly new kind of knowledge, a knowledge that neither books nor worldly experience can impart. Muscles, I found, were strength as well as form, and each complex of muscles was subtly responsible for the direction in which its own strength was exerted, much as though they were rays of light given the form of the flesh … For me, muscles had one of the most desirable qualities of all: their function was precisely opposite to that of words.

The ability to project your body in a powerful manner can truly make you reevaluate the space you inhabit. One becomes, as Mishima would say, self-aware, and this is different from just merely “existing.” By way of example, we can ponder our existence, whether or not we choose to feel happy or sad, but at some point, those moments pass. They are fleeting, at best, and our minds often flicker between opposite ends of our emotions.

One of the remarkable characteristics of our bodies is just how much they seem to value the preservation of our muscles. They do, however, require a commitment from their owner to continually defy homeostasis, the body’s attempt to keep our organism in balance. Muscles are summoned when you lift, as your body begins to pump blood into the particular area you target. Bodybuilders call this the mind-to-muscle connection, a way of focusing on the biomechanics of a particular muscle being trained so as not to let one’s attention drift away from the activity. It is a form of self-awareness, like trying to unravel a difficult passage in philosophy to understand the greater meaning of a given text. And like the study of philosophy, understanding the individuality of each muscle leads to a greater sense of self-awareness for the whole. Lifting taught me to no longer see my body as operating on a kind of autopilot, subject to the whim of my biology’s homeostatic fluctuations to preserve a kind of mere existence. Instead, I discovered that my body needed to be given a role, a sense of purpose, and a mode of expression that fostered athleticism and growth. This is precisely what Mishima meant when he spoke of the language of the flesh, on par with how studying philosophy, for example, gives us an organized lens or even worldview.

In the first year of transitioning from casually working out to a more disciplined endeavor of daily training, I spent hours looking at various golden-age bodybuilders like Frank Zane and Arnold Schwarzenegger. I was captivated by their lines and muscular symmetry—of a form of the human body I barely knew existed.

Our minds, Mishima states, have an uncanny ability to envisage all kinds of fantasies and senses of wonder. But in the end, sadly, these daydreams leave the bodies we possess behind. We can only have an idea of what it is like to have such an impressive physique but that’s not the same as being self-aware of having one.

This is naturally different from when it comes to inducing the brilliance of our minds. We all have heard stories of the physicist who sketches out a groundbreaking theorem on a cocktail napkin, or a software savant creating a new programming language—but all of these epiphanies, whether they’re big or small, can more or less happen at any time and any place. The same cannot be achieved for the body. Certainly, there are many places to build muscle, such as at a gym or in a park—but the process of physically building the body is governed by so many other factors that are, in some ways, fundamentally at odds with how we may think through an idea in our beds late at night.

In Daniel Kunitz’s Lift, he directs the reader to consider how Plato was depicted in ancient art, as not just a great thinker, but one who was adorned with a crown of laurels, a symbol that was symbolic both theologically and athletically. The gymnasium was a site of education, worship, as well as general erudition for male Greek citizens. The Olympic Games were not seen as they are today—displays of athletic feats with deeply nationalist undertones—but were associated with worship and virtue. That our association of building muscle under modernity is limited to a hobby—or, at worst, a practice of vanity—is a sad departure from what Mishima would have hailed as a thoroughly classical education. The steel, as Mishima reminds us, is the only way to conjure up these dead notions of the language of the body, just as one would resurrect classical knowledge from Latin or Greek.

Mishima’s essay is a portrait of an intellectual who understood the development of one’s physique as more than what the marketing hook used by the gym companies offers. He imbued the term “skin deep”—or, as he put, “the surface,” with a new meaning. It is no coincidence that, as Japan was emerging into a new era of consumption, Mishima used the opportunity to effectively embrace a core tenet of the very modernity he sought to rail against—the desire to remake oneself. As for today, in an era where dead-end jobs in the service sector continue to monopolize the employment market in the United States, the very hobby-like impression we have of exercising bears serious reexamination. In 2019, I was interviewing a Brazilian sociologist and internationally ranked female powerlifter and asked her why so many people were joining the sport of powerlifting. She told me what many other powerlifters, bodybuilders, and Olympic weightlifters have said to me since: there is a deep sense of empowerment that comes from creating yourself out of what you once were—and then demonstrating it.

It is why the sun figures so strongly as a metaphor in Mishima’s essay. It is revelatory by nature. Sunlight commends muscles to be revealed from the confines of dark, intellectual musings where the body lies hidden and out of focus. And even while clothing today has become more sleight-of-hand than accenting the true form of one’s physique, the sun rarely misses a chance to illuminate all of our details. “Finespun and impartial,” writes Mishima, “the summer sunlight poured down prodigally on all creation alike.”