Academic Free Speech

Free Speech and Due Process at Princeton: The Case of Joshua Katz

The treatment of a dissident professor raises serious questions about the university’s actions

My longtime Princeton University colleague Joshua Katz, a distinguished classicist and linguistics scholar, was recently dismissed from his tenured position by Princeton in a case that has received international attention. I was Professor Katz’s official Adviser in Princeton’s disciplinary system through the course of the entire four-year long ordeal that resulted in his dismissal. In that capacity, I came to possess information that is privileged or confidential, and therefore cannot be shared. I will herein discuss only information that is already publicly known.

As a matter of full disclosure, I should note that when Professor Katz asked me to serve as his Adviser, which is something I had done for others over the course of my time at Princeton, he and I were mere acquaintances (though I knew him by reputation as an outstanding scholar, and an exceptionally gifted and dedicated teacher). We have since become close friends.

Princeton conducted two investigations into conduct by Professor Katz in connection with a consensual but (under the university’s rules) impermissible relationship he had with a student under his supervision in the mid-2000s. The first investigation was conducted a bit over a decade after the affair had taken place, when a third party informed university officials about what had happened. When those officials confronted Professor Katz, he immediately admitted to the offense. Essentially, he pled guilty to having had the affair.

The former student with whom Professor Katz had the relationship was asked by the university’s investigators to assist in the investigation and disciplinary process, including by making any claims she had against Professor Katz arising out of the affair and providing evidence. She declined to make allegations of any kind, refused to participate in the proceedings, and expressed disapproval of the proceedings going forward.

Unbeknownst to me, she and Professor Katz had remained in communication (though with no personal meetings, or romantic or sexual elements in the relationship), and she expressed to him the desire to have her privacy respected and not to be dragged into the matter. He told her that he would answer all questions put to him by the investigators fully and truthfully, but would not on his own initiative discuss or seek to involve her in any way. The proceedings went forward, eventually resulting in a punishment consisting of a one-year suspension without pay. Professor Katz was also required to meet regularly for four years with a counselor. Properly, none of this was publicly disclosed at the time.

After serving his sentence, Professor Katz returned to teaching, but soon became the subject of controversy when he publicly criticized a July 4th, 2020 “Faculty Letter” from colleagues making demands for new Princeton policies (or alterations of existing policies) in order to combat alleged systemic racism. Some of the demands were aimed at creating university policies that would jeopardize academic freedom. Others would have subjected the university to possible legal liability for violations of laws prohibiting differential treatment based on racial classifications (including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964).

As Professor Katz noted, the Faculty Letter contained

dozens of proposals that, if implemented, would lead to civil war on campus and erode even further public confidence in how elite institutions of higher education operate. Some examples: “Reward the invisible work done by faculty of color with course relief and summer salary” and… “constitute a committee composed entirely of faculty that would oversee the investigation and discipline of racist behaviors, incidents, research, and publication on the part of faculty.”

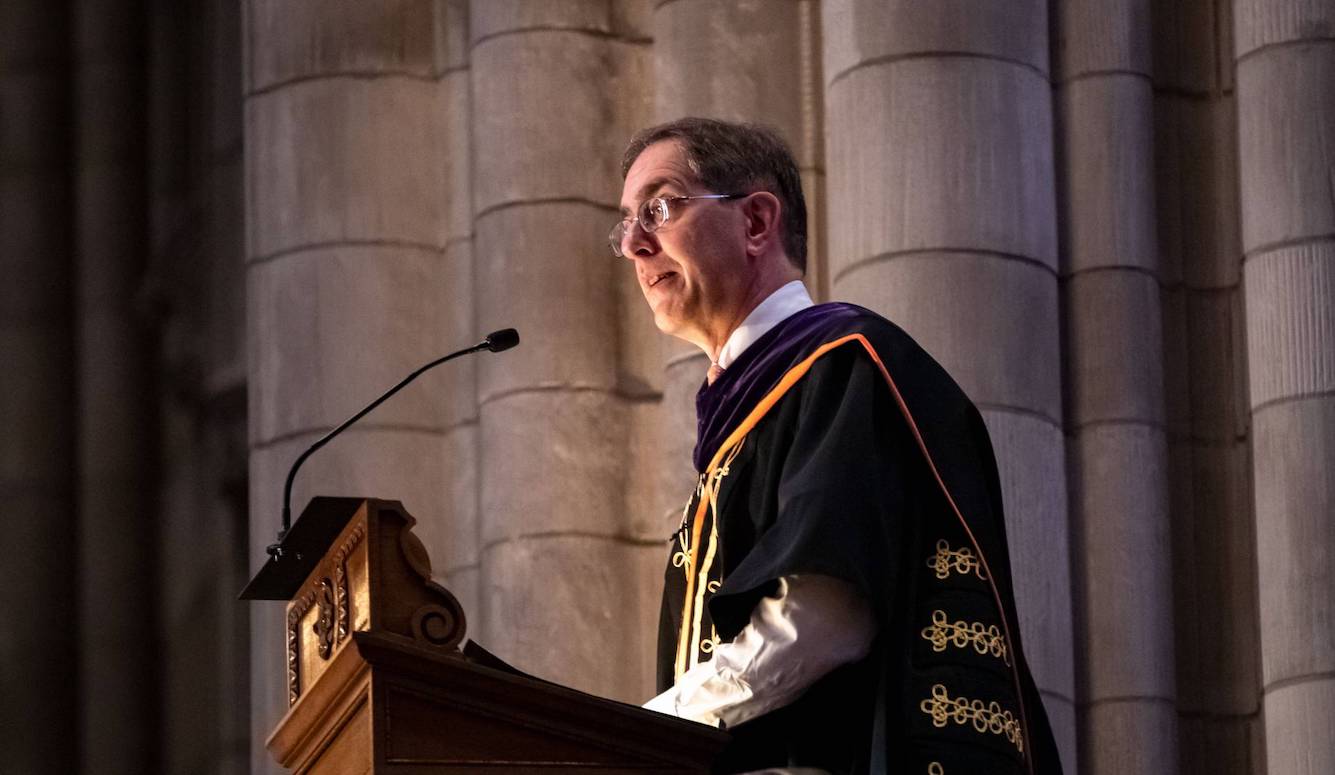

In his article, published by Quillette, Professor Katz also referred to a by-then-defunct student organization (whose members had graduated) as “a small local terrorist organization that made life miserable for the students (including the many black students) who did not agree with its members’ demands.” This language outraged some on the campus left, and Professor Katz’s article, titled “A Declaration of Independence by a Princeton Professor,” was condemned by Princeton’s president, Christopher Eisgruber.

Bravo to this honesty. Since May I have gotten almost an email a day from a professor who fears speaking out against the modern distortion of progressivism would get them fired. https://t.co/iOhF1p9cKD

— John McWhorter (@JohnHMcWhorter) July 12, 2020

A university spokesman—not the president—went further by suggesting that Professor Katz might be subjected to some sort of investigation for his words. A little over a week later, President Eisgruber made clear that this would not happen, and reaffirmed Princeton’s strong respect for freedom of speech. I praised President Eisgruber for standing firm on the principle of not punishing protected speech, even when he himself regarded the content of the speech as profoundly wrong. (As it happens, I had intimate personal knowledge of the mistreatment of black students by the group that Professor Katz had criticized. Based on that knowledge, I did not think what he said about the group was out of line. It certainly was not racist—quite the opposite.)

In this time of testing, Princeton University and its leadership passed the test--as I knew it would--remaining true to our principles even as passions we are all feeling flare. https://t.co/0hUs9mP99U

— Robert P. George🇻🇦🇺🇸🪕 (@McCormickProf) July 28, 2020

That is where the matter should have ended. Regrettably, it did not.

Woke elements on campus, including at the student newspaper, were angry with President Eisgruber as well as Professor Katz. They began trying to dig up dirt, to find another way to get the professor disciplined—even fired. They had heard rumors of an affair with a student and noticed that Professor Katz seemed to have had an unexplained off-cycle leave of absence. They demanded information about the matter from the university.

Initially, the university was prepared to stick to its standard practice of responding to such “demands” by saying that it does not discuss personnel matters. Soon, however, university officials informed Professor Katz that either he would have to tell campus media about the disciplinary action that the university had taken against him, or they would do so. We pleaded with university officials to stick to its standard practice. But they refused.

So, basically having no choice, Professor Katz told the story. Most unfortunately, at this point, the alumna with whom he’d had the affair (by now, nearly a decade and a half earlier) turned on him and filed complaints with the university. She made various claims, but only one survived and became the focus of a new investigation. This was the claim, now publicly known, that during their affair, Professor Katz discouraged the woman from receiving needed mental health care in order to prevent their relationship from being revealed.

In certain subsequent (non-contemporaneous) email communications with the woman, he seemed to have confessed to doing this. This “confession,” however, was in the context of trying to calm her down when she was obviously extremely upset; and, as the full email record shows, he was “confessing” to every allegation she made against him, including ones that were demonstrably untrue.

In my official role as Adviser, I argued that a second investigation should not take place because it resembled what, in the criminal justice system, would be double jeopardy—i.e., subjecting an accused person to a second prosecution for the same offense. The woman had been given every opportunity, and had indeed been encouraged, to make allegations and provide evidence of wrongdoing in the first investigation. She declined to do so. Indeed, she opposed the investigation and refused to participate. It would therefore be wrong to investigate and discipline Professor Katz a second time for allegations arising out of the nexus of facts that gave rise to the first investigation and to the punishment imposed in light of Professor Katz’s confession of guilt.

Although I continue to believe that my argument regarding double jeopardy was sound and should have been accepted, ending this whole business, it was rejected at every level of the disciplinary proceedings, including when the university president recommended to the Board of Trustees that Professor Katz be fired.

My difference of opinion with top university officials does not concern free speech. It concerns due process. These officials, as I understand their position, believe that because the specific allegation made by the woman was new, investigating it, prosecuting it, and punishing Professor Katz on this basis did not amount to trying someone twice for the same offense. For the reasons indicated, I disagree (even if what we are talking about here is a university disciplinary proceeding, to which the constitutional prohibition on double jeopardy in criminal cases does not apply).

Having said that, however, it must be added that the second investigation would not have been initiated if it hadn’t been for student journalists and others with a vendetta against Professor Katz, and who were seeking to dig up dirt on him because they disliked his expressed views. This element really makes the whole business a terrible injustice as well as a personal tragedy—as well as drawing in the issue of free speech, albeit in an indirect and complicated way.

I should add that I personally do not believe that Professor Katz actually tried to prevent the woman with whom he was having an illicit affair from getting the mental health care she needed: As noted above, his emailed assent to this accusation came in a context in which he might have confessed to any number of fictional crimes. But again, this difference of opinion between me and university officials is not about free speech, but rather about interpreting the available evidence. (There were other claims against Professor Katz that arose during the second disciplinary procedure, and which were mentioned by the university. On these, too, I disagree with the findings that President Eisgruber ultimately accepted, though I won’t go into the details here, as they are secondary to my broader argument that the entire second investigation was a form of double jeopardy.)

There was also a separate scandal that arose from the manner by which (as yet still unidentified) university bureaucrats smeared Professor Katz as a racist through a freshman training program called “To Be Known and Heard: Systemic Racism and Princeton University”—even going so far as to bowdlerize a quotation from him as a means to support this defamation. Specifically, the words “including the many black students” were removed from the aforementioned quotation, “a small local terrorist organization that made life miserable for the students (including the many black students) who did not agree with its members’ demands.” The document also contained statements from detractors, such as “[Katz] seems not to regard people like me [a Black professor] as essential features, or persons, of Princeton,” with no opportunity for Katz or anyone supporting him to reply.

I can think of no possible explanation for this outrageous conduct other than it being a form of harassment and retaliation against Professor Katz for his speech. When the office responsible for the freshman-orientation materials was called out for the doctoring of the quotation (Professor Katz’s lawyer, Samantha Harris, had complained to the university counsel’s office directly about this issue) someone restored the full quotation on the “To Be Known and Heard” website. But the university refused to apologize to Professor Katz or—and this is critical—inform the students to whom he had been smeared that the quotation had been bowdlerized and had to be corrected. So the correction was essentially meaningless and did not undo the injustice to Professor Katz.

A group of professors led by mathematician Sergiu Klainerman filed a grievance in their own names, not on behalf of Professor Katz himself, demanding an investigation into who had retaliated against him by weaponizing the university’s freshman-orientation materials in this manner. Two Princeton officers, the Vice Provost for Institutional Equity and Diversity, and the head of the Human Resources department, were evidently assigned to look into the matter and respond to Professor Klainerman and his co-complainants. In a ruling that I found ridiculous, these officials rejected the complaint on various grounds.

Perhaps only people who lived under communism fully grasp what is wrong with American universities today. Sergiu Klainerman defends Joshua Katz and exposes the doublethink of @Princeton's President Eisgruber: https://t.co/Ao7e1ft5g8

— Niall Ferguson (@nfergus) April 12, 2022

Professors Klainerman et al. eventually appealed to a standing faculty committee that has the power to review faculty complaints against administrators’ actions and make recommendations (the Princeton Committee on Conference and Faculty Appeal being its full name). I understand from reports that I regard as completely reliable that the committee ruled in favor of the Klainerman group, and against the two officers who had dismissed their complaint, unanimously on every count.

And so even though Professor Katz has already been terminated, important issues surrounding his mistreatment persist, as the Committee on Conference and Faculty Appeal’s apparent recommendation of a full investigation of the defamation of Professor Katz by university officials now sits with President Eisgruber. A public statement by the president made in response to a public letter authored on behalf of the Academic Freedom Alliance by Keith Whittington—a Princeton professor and an eminent scholar of constitutional law who’s literally written the book on campus free speech—suggests that the president views the statements about Professor Katz contained in the freshman orientation materials as themselves protected speech under Princeton’s free-speech policies. I strongly disagree with this characterization, as Princeton’s free-speech rules expressly exclude expression that “falsely defames a specific individual.” And I hope that, on reflection, and in light of the findings by the aforementioned faculty committee, President Eisgruber will order an independent investigation of the smearing of Professor Katz, with attendant disciplinary proceedings concerning those responsible.

There is no question in my mind as to whether Katz was defamed—treatment exacerbated by the fact that the freshman-orientation materials are promulgated to a captive student audience. Nor am I in any doubt as to whether the underlying motives were malicious. The bowdlerization of Professor Katz’s words was done with the evident intention of depicting him as racist—which he is not. The only real questions are who is responsible, and what is the proper disciplinary action under the university’s rules.

If Princeton bureaucrats, whoever they are, can get away with retaliating against a professor for his protected speech by smearing him in this way, then the university’s formal free-speech protections are mere parchment guarantees. President Eisgruber, himself an eminent First Amendment scholar, should understand what is at stake here. He has always been a powerful defender of free speech and other basic civil liberties. (I should add, again as a matter of full disclosure, that he and I are old friends.)

I have publicly praised him for those qualities and, as noted herein, acknowledged that his decision regarding the second investigation of Professor Katz does not directly compromise free-speech principles. Thus, I have reason to hope that a proper understanding of what is and isn’t protected speech under university policies will guide him toward an appreciation of the injustice done to Joshua Katz.