Indigenous History

Canada’s Racial Balkanization

With their newfound fixation on race and bloodline, Canada’s WASP elites are channelling a mindset that I thought I’d left behind in the former Yugoslavia.

Far from Toronto’s downtown, in the land of subdivisions, six-lane traffic, and strip malls around Lawrence Ave. East and Bellamy Rd., sits one of the oldest cemeteries in North America. The grass of the modest municipal park named Tabor Hill covers the ossuary of the Huron-Wendat people dating back to the pre-contact 1300s. Ossuaries like this one were built during the 10-day festival of the dead, as described in the 1600s by the French Jesuit settler to Nouvelle France Jean de Brébeuf, and centuries later confirmed by modern archaeology. When a Huron village depleted its resources, its residents would move to another location, taking their temporarily buried relatives with them. (It won’t be hard to guess which of the two sexes had the duty to clean the remains and prepare them for the passage.) On some occasions, several villages would gather to build one common burial ground—as they did on Tabor Hill.

Far from Toronto, over in what was once called Nouvelle-France, the Huron had invited Brébeuf to join the bones of the deceased French to their own buried ancestors, a nation-building act avant la lettre, perhaps from an intuition that a multi-confessional society lay ahead. Being a Catholic, Brébeuf could not imagine that in the course of the Second Coming, the Saviour, coming across such an ossuary, would be even remotely able to handpick the saved from the infidels for the purposes of the resurrection of flesh, and so gave it a pass.

These Huron burial practices petered out over time, and the Huron confederacy dispersed. The decline was partly due to diseases brought over by Europeans. But wars with another Indigenous group, the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee, were also to blame. (The Tabor Hill plaque, in one of those ironies that historical mappings are rife with, indicates that the ossuary was Iroquois. But even following the discovery, by city archaeologists, that it actually belonged to the Huron, the plaque was never updated.)

The conflicts and differences among the Indigenous peoples preceded the European arrival, and these rivalries were then exacerbated by the fur trade and the general jostling for resources and territories among the colonies. Sides were taken, alliances formed. Indigenous groups fought on different sides in The Seven Years’ War between the French and the British, and they fought on the side of British North America in the War of 1812 against the American republic. Canada’s first peoples have been just as unified a world-historical subject as Europeans—in other words, not at all.

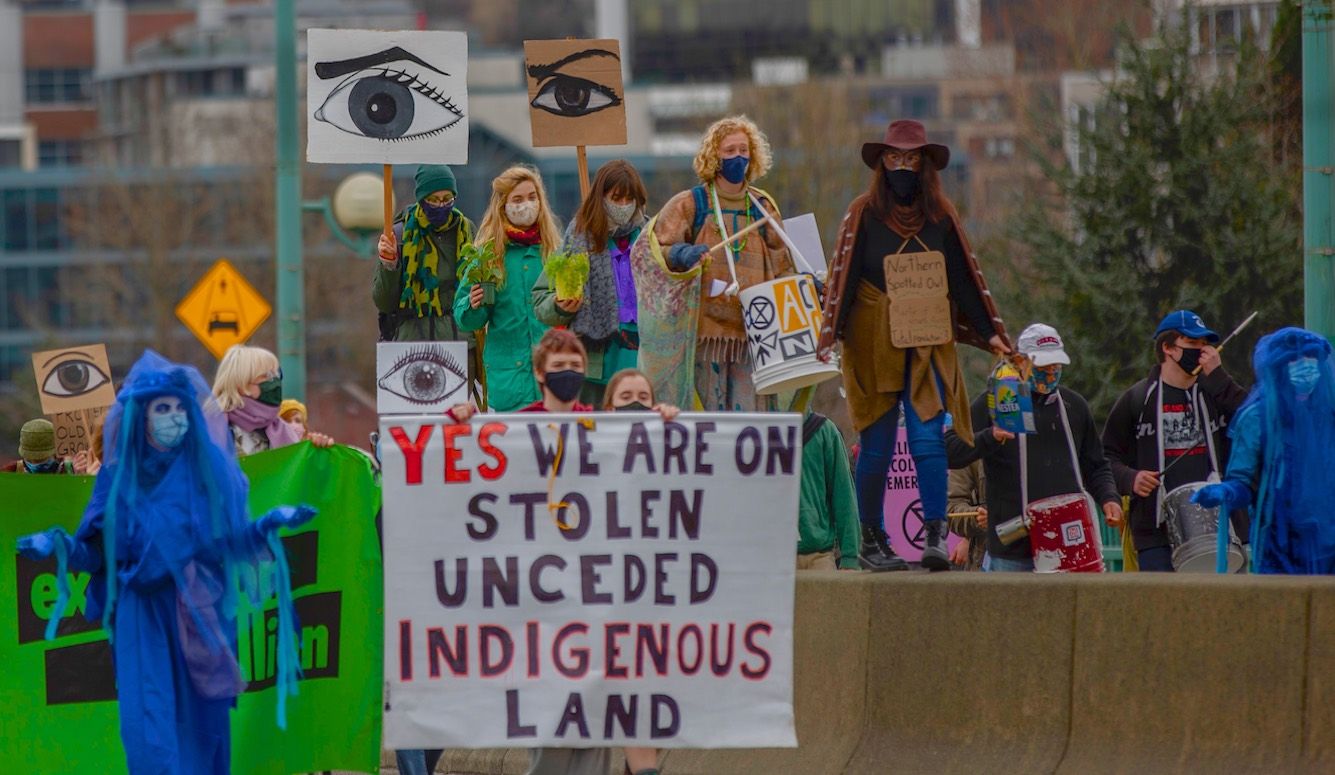

Therefore, the land acknowledgements recited before practically all cultural and education events in Toronto as of late do not quite tell the whole truth. “We acknowledge that this event takes place on the lands occupied for centuries by the peoples X, Y, and Z and we are grateful to them to be here” obscures the fact that possession of the land was contested among those groups. Land acknowledgements are a collective saying of grace, in effect, while they teach no history, and do nothing to improve actual Indigenous lives.

Stuart Reges, thoughtful computer science iconoclast at the University of Washington, is in hot water again. This time for writing his own syllabus land acknowledgment, which didn't go over too well with the administration https://t.co/Nwfa6E0GE6

— Claire Lehmann (@clairlemon) January 12, 2022

Yet they are everywhere. I once attended a Liederabend (evening of song) that began with the young soloist asking the audience to read aloud the land acknowledgement projected on the subtitles screen. A theatre-season launch opened with a 10-minute smudging ceremony, the context or the purpose of which was never explained. Saying grace before unrelated events (whether in performance of atonement or perhaps in search of validation) is just one aspect of the “Indigenization” process (the term “reconciliation,” itself vague and pious, now no longer being seen as adequate) that old-stock Anglophone Canadians have embraced with unusual ardour.

As an immigrant to Canada from the western Balkans, I became uncomfortable with the suggestion that one’s ethnicity gives you a special relationship to a piece of land—because the pursuit of that political idea has been ravaging my continent of origin for millennia. When I complained on Twitter about having to observe mandatory smudging ceremonies at opera-season launches, an activist asked me why I don’t go back to where the rituals that I find meaningful connect me to the land where I am from. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to talk to Canadian progressives if such talk of blood and belonging, and of rituals specific to a stretch of land, are not your thing.

The Twitter activist in question, by the way, was not from around Toronto either: She grew up on the west coast of Canada, among very different Indigenous groups than the ones that inhabit the old Canada of Ontario and Quebec. What do all the first peoples have in common, exactly? Languages are different, weather and geography are different, and the degree of interest in being integrated into liberal democratic procedures and capitalist production varies among groups. These differences, as a case involving the Wet’suewet’en First Nation recently showed, sometimes can even split elected and hereditary representatives within the same group.

Another detail that gets obscured by land acknowledgements: Many of the most prominent Indigenous-rights advocates have a mix of western European and Indigenous parentage, making them more Western European and WASP or Celtic than the Slav writing these lines. But the Indigeneity takes primacy in their personal history, to align with the person’s politics, to fit in the dominant mode of political contestation of the era.

In recent years, the division of the Canadian population between Settler vs. Indigenous has sharpened, conceptually and politically, as much as the division of black vs. white in the United States. Effectively, peoples who have little in common are imagined as one ethnicity (the non-Settler) inhabiting one economic position (reduced to poverty by past and ongoing colonization), and possessed of one possible psyche (traumatized by past and ongoing colonization, permanently devoid of agency).

While conversations about race in the United States feature many notable dissidents (including Thomas Chatterton Williams, Kmele Foster, John McWhorter, Chloé Valdary, Glenn Loury, and Coleman Hughes), there are virtually no progressives north of the border who will argue that impoverished Indigenous and economically disadvantaged immigrants have more in common with each other than either of these groups have with the well off members of their own ethnic cohort. Or, to put it more broadly, that Canada is one country, to which people from around the world emigrate to escape ethnic and religious over-determination—a project very much worth keeping alive.

“Indigenization” is a value adopted by a growing number of institutions. But what does that look like, apart from land acknowledgements? A few examples. Mandatory Indigenous-themed content in education; and if this happens to clash with academic freedoms, too bad for academic freedoms. It’s quite legal to restrict academic job openings in Canada to certain ethnic groups or under-represented demographics. A project to “decolonize physics” got a lot of government funding recently. A part-Indigenous, part-South Asian playwright asked the Toronto media not to send a “white” critic to review her play; many in the theatre world applauded, and a national newspaper sort of complied (they sent an additional, ethnically-correct critic alongside their usual one). The Canada Council for the Arts recently hired an Indigenous activist-journalist as its chair. His goal? To reduce “the harm” inflicted by pesky colonizing arts grants.

Why playwright Yolanda Bonnell asks that only people of colour review her play Bug. https://t.co/WDmg26xYnR

— CBC Books (@cbcbooks) February 10, 2020

Meanwhile, in the field of literature, writers are terrified of accusations of cultural appropriation, of getting into the same pickle as Angie Abdou, a writer who followed the prescribed procedures for writing about an Indigenous group in fiction, and was still found wanting, criticized by her WASP peers and Indigenous groups alike. The long-term effect of this tension will shape up as two separate literatures, one legitimately Indigenous, and one for the rest of Canada, devoid of Indigenous characters. Some competitions for writers-in-residence already advertise that they are open to “Canadian and Indigenous writers.”

This paradigm also feeds a booming educational-legal-media industry that profits off the othering of Indigenous peoples: interpreting what they are, what they want, what they are entitled to, and how they are fundamentally different from everybody else in Canada. A majority of the culturati and progressive media understands the country as existing on a bunch of unceded territories, akin to a random drawing on a napkin.

Has the increasing separateness of Indigenous peoples in the Canadian project made their lives better? They are still overrepresented in statistics tracking femicide, suicide, and incarceration, and disproportionately affected by the lack of basic infrastructure on self-governing reserves. Now that separateness has been tried, would somebody please advocate for more closeness and more belonging, so that these societal problems are understood for what they are: problems that we as a country and our children (not “they” and “their” children) are facing?

Because we do share a lot of problems. The writer Sherman Alexie once said that immigrants and the Indigenous share much in common. Structurally, we’re outside the dominant culture, with similar problems of belonging. But when I say we share a lot of problems, I mean all of us, the Canadian-born as well. Our national economy relies too much on resource extraction. We work too much for what we earn—we work too much period—at jobs that don’t fulfill most of us. The value of the arts in our lives is diminishing. We read fewer books, and make fewer friends. We often cocoon in our own ethnic groups. We can’t really navigate our cities without an automobile. We are dependent on American screens. We know more about American politics and culture than our own. Especially in urban centres, we find it harder and harder to pay our rents and mortgages.

In Toronto, in particular, I would argue, the greatest divide is not between the sexes or the races, but between the owners and the renters. It is all about the land in one of the most expensive cities in North America, but not in the way we believe.

Toronto ranked one of the most expensive cities in the world to build a house https://t.co/IMlj5VdDjg #Toronto #TorontoRealEstate #RealEstate

— blogTO (@blogTO) January 21, 2022

Most of Toronto is taken up by what city planners call the yellow belt—single-family houses with back and front yards and garages. For generations, municipal politicians have been loath to permit a continued gentle densification of this area—five-storey walk-up apartment buildings remain rarities (because well-organized, middle-class home-owners, conscious of their property values, are the people who vote in Toronto’s municipal elections). Meanwhile, the re-densification of the urban core proceeds apace. The growth has been mostly upward: older walk-ups and parking lots are being replaced by 50-storey condominium buildings.

Many people among those reciting land acknowledgements at performing-arts events in Toronto are home-owners and even second-home-owners. How about, instead of an Indigeneity fantasy that allows WASP Canadians the enjoyment of blood-and-belonging by proxy, we increase densification in the yellow belt, and build affordable apartments so low-income and middle-income people of any ethnicity can live anywhere in the city? Yes, the birth of Toronto through the establishment of single-family property lots did happen through colonial settlement. How about mixing it up a bit with some semblance of rent control—how about that kind of decolonization?

In spite of the current trend toward Balkanization, polarization, and racializing, we are one polity. It’s bizarre that someone who has lived here only since 1999 has to keep saying this to people whose ancestors in this country go back many generations. The sooner we realize this, the faster we can begin to tackle the issues that affect everyone—including the severely unaffordable housing in urban centres, overwork and underemployment, mental health, and quality of life.

Excerpted, with permission, from Lost in Canada: An Immigrant’s Second Thoughts, by Lydia Perović. Published by Sutherland House. Copyright © 2022 by Lydia Perović.