Politics

Revolution Betrayed

A review of The Right: The Hundred-Year War for American Conservatism by Matthew Continetti, Basic Books, 496 pages (April 2022)

“So inevitable and yet so completely unforeseen” was Alexis de Tocqueville’s verdict on the French Revolution. Much the same can be said of Donald Trump’s hostile takeover of the Republican Party and the conservative establishment, which by 2016 had lost the strength and the will needed to contain a prince acting like a beast (to borrow Machiavelli’s phrase) in their midst.

Since the end of the Cold War, the trajectory of the American Right has been unrelievedly grim: a political movement stuck in ideological nostalgia whose traditional constituency is dwindling with each passing election. Instead of responding to novel circumstances in a rapidly changing country with a forward-looking agenda, the Right was shackled to “the carcass of dead policies,” as a great British conservative, Lord Salisbury, might have put it. With the enthusiastic backing of an insular conservative institutional superstructure, the Republican Party presented an obsolete program in a bombastic tone that repelled the very voters it desperately needed to win.

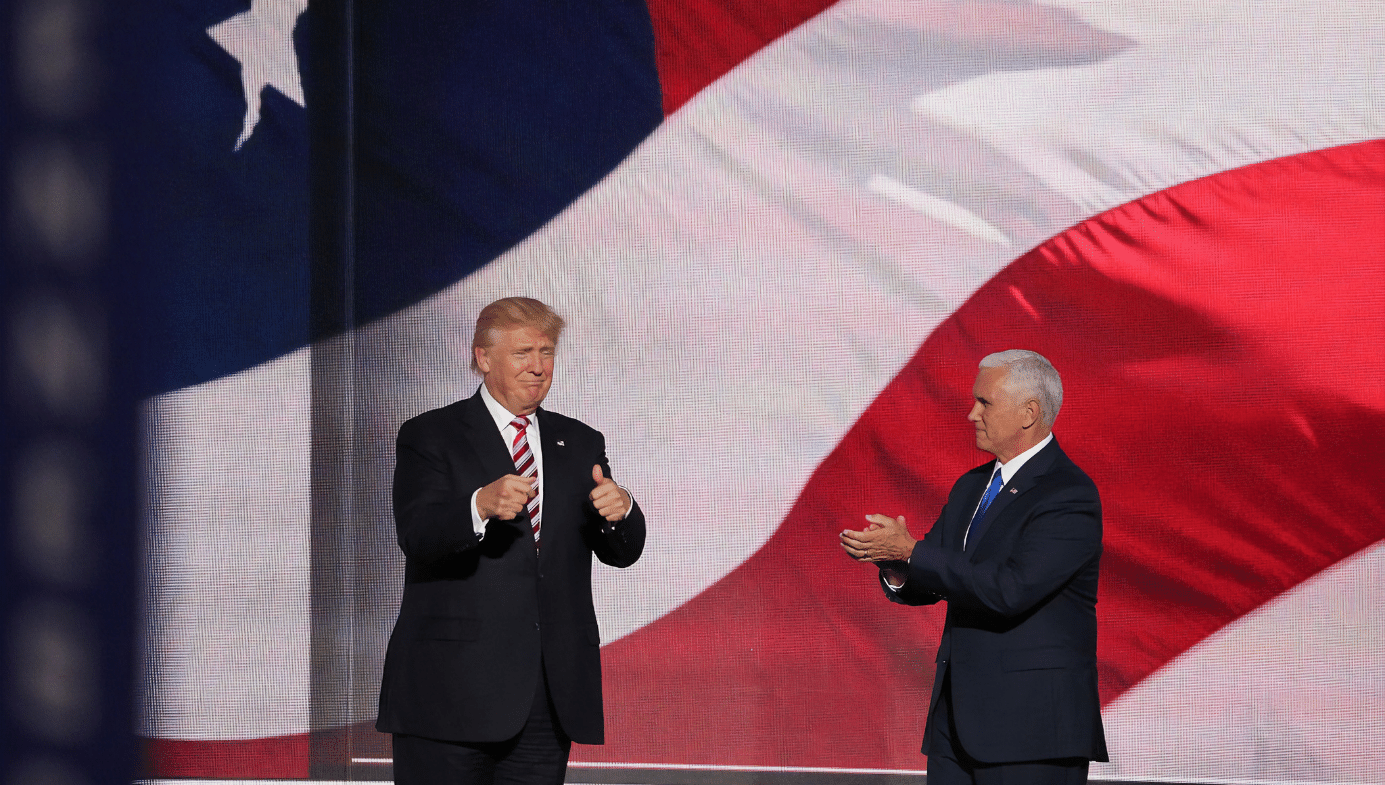

However far-fetched Trump’s political ascendancy may have seemed before he entered the White House with the GOP’s imprimatur, it was made possible, and somehow inescapable, by a Right that had long ceased to show much of a pulse. In an era of unprecedented deficits, stalled social mobility, and Gilded Age-levels of inequality, the Grand Old Party—the customary instrument through which the conservative movement sought to influence national policy—represented a reactionary politics of cultural resentment and economic austerity. This peculiar synthesis was perhaps best embodied by the party’s vice-presidential nominees in 2008 and 2012: Sarah Palin and Paul Ryan, respectively. Against the backdrop of mounting social division and decay, Republicans became simultaneously more populist and more plutocratic, presenting incomparable opportunities not only for the opposition party but for designing and unscrupulous outsiders.

When the most talented of these demagogues made his move, many Americans across the political spectrum were baffled as well as repelled. And yet, Trump’s initial triumph and abiding influence attest not only to a reoriented political culture but to a Right that has become, in decidedly un-conservative fashion, a slave to its impulses rather than their master. The decline and fall of American conservatism in our time recalls Hemingway’s description of the process of bankruptcy—it proceeds at first gradually, then suddenly.

This is the story of The Right, Matthew Continetti’s important and troubling new history of modern American conservatism. Superior to any previous volume on this critical subject, it brings a steady and penetrating gaze to the collapse of conservatism in America in the 21st century, and explains how the political party long devoted to its cause has spurned it thoroughly and comprehensively in favor of a personality cult with authoritarian overtones.

A journalist and senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, Continetti is an expert witness on the ideology of “free minds and free markets” that long defined American conservatism. Honest in conception and marvelously accurate in detail, The Right casts a somewhat jaundiced eye on that tradition but shows a tenacious sympathy for it all the same. At least as a historical matter, the American Right has been distinguished by its devotion to the tradition of constitutional self-government and individual rights. If there’s any shame is to be felt about or within such a political faction, it is chiefly because it departed from those sound moorings at precisely the moment they were most necessary.

But the tangled story of how the GOP came by them in the first place repays attention. The architects of America’s constitutional order were conservative-minded men with a healthy suspicion of the masses who sought to devise a regime suited to human nature. Although the founders hailed from a recognizably Anglo-American conservative political tradition, they set themselves apart by defending an a priori truth deemed “self-evident”: that all men are created equal, and that any government is tasked to protect the individual in his private pursuit of happiness. America’s conservatism, in other words, has been the exceptional conservatism of a forward-looking republic rather than the dour Toryism of old Europe.

What Continetti calls “the hundred-year war for the Right” erupted in earnest when the Republican Party rejected progressivism’s attempt to overturn this political inheritance. On a platform of economic freedom and nonintervention abroad, Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge promised a return to “normalcy.” It wasn’t long before history conspired to demolish this fragile status quo, first with the Great Depression and subsequently with the outbreak of the Second World War. Although the world’s harsh realities put paid to this parochial doctrine, it never quite lost its luster in the conservative imagination.

Postwar American conservatism retained its visceral opposition to progressivism at home, but adopted a militant resistance to Soviet totalitarianism abroad that banished its old neglect of global responsibility and activism. It was this latter modification that made the Right such a potent force in American life for the duration of the Cold War as anticommunism became the rallying point for religious conservatives, economic conservatives, and foreign policy realists. A clique of ex-Communist intellectuals, including James Burnham, Whittaker Chambers, and (later) Irving Kristol, also migrated to the Right, providing a previously lacking intellectual vocabulary (and a touch of cultural sophistication) for conservatives enlisted in the fight for the free world.

The most vital platform and debating chamber in the universe of intellectual conservatism was National Review, which issued a resounding statement of intent in 1955: the magazine “stands athwart history, yelling Stop.” In his depiction of the conservative establishment, Continetti lays appropriate stress on the journal and its impish and indefatigable editor, William F. Buckley, Jr. Aghast at the growing fashion throughout the West for atheism and collectivism, Buckley sought to transform American conservatism from a din of regional dogmas into a veritable national canon (hence the title of his magazine).

Buckley became the enfant terrible of the Eisenhower years as he tried—not without success—to mainstream conservatism in America. The editors of National Review described themselves as “radical conservatives” pursuing the “restoration” of the pre-New Deal state. However impressive in scope, this undertaking was marred by errors and excesses that limited its reach and left it morally diminished. In the charged climate at outset of the Cold War, Joseph McCarthy was admitted into conservative trenches along with Generalissimo Franco. And it was to the movement’s “enduring shame,” as Continetti justly asserts, that conservatism’s flagship journal made common cause on civil rights with racist Southern Democrats. Contending that human equality would carry America along the road to serfdom, Buckley foolishly disregarded the bedrock truths of the American founding in addition to the Straussian forces on the Right who opposed progressivism and supported civil rights.

In the course of deprecating Eisenhower’s middle-of-the-road Republicanism (and later Nixon’s “street-corner” variety), Buckley fashioned “fusionism” out of the three fractious components of nascent conservatism: traditionalism, libertarianism, and anticommunism. Having included a range of friends and allies within his latitudinarian conservatism, Buckley didn’t hesitate to erect some barriers to entry. In spite of its natural partisan edge, in other words, National Review didn’t pursue a right-wing version of the old Popular Front slogan: “Pas d’ennemis a gauche, pas d’amis a droit” (“No enemies to the Left, no friends to the Right”). In assailing the Left, Buckley gave no quarter to “the irresponsible Right.”

The most disreputable and outrageous claimants to the conservative mantle found themselves read out of the movement. In the 1950s, Buckley went out of his way to sideline antisemitism on the Right. Gerald Smith and his Nationalist Christian Crusade were an obvious target. In the 1960s, Buckley forswore the conspiracy theories of the John Birch Society. In the 1970s, he renounced his past support for segregation. It became clear that gadflies like McCarthy and George Wallace, and libertarian dogmatists like Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard, were no longer welcome. (The author of Atlas Shrugged returned the compliment, deeming National Review “the most dangerous magazine in America.”)

The intellectual rigor of the conservative movement was matched only by its self-confidence. William Rusher, the publisher of National Review, was engaged in a “radical operation” to “redesign the intellectual premises of the modern world.” This hardy sense of purpose was broadened and deepened by other precincts of the Right, including in other journals such as the Public Interest and Commentary and later the Weekly Standard. The neoconservative influence on the Right was philosophical as well as practical: these disaffected writers and intellectuals, initially based largely in New York, “believed that they were defending liberalism, not negating it as more traditional conservatives sought to do.” And instead of hankering for “tradition in the abstract,” they brought a learned and living focus to the concrete social policies that were fostering demoralization and dependency in the underclass.

This flurry of activity was not confined to the world of ideas. The modern Right flared into the political arena first with Barry Goldwater and then more fruitfully with Ronald Reagan. Movement conservatism was given its chance when the chaos of the late 1960s and 1970s helped to discredit the New Left and the Democratic Party. The conservative creed resonated deeply with a public that was at once outraged and injured by the unchecked surge in crime, inflation, and national humiliation.

With American society in crisis and its global stature on the wane, the Right, reinforced by waves of neoconservative defectors from the Left, was able to appeal to the mainstream with an account of what had gone wrong in American life and how to remedy it. After Reagan’s election in 1980, the cause of economic and political freedom was equipped not only with a movement but a party. And for the first time, there was an unapologetic Republican Cold Warrior in the White House who understood that morality and power were vital ingredients of an effective foreign policy. (Continetti reminds us that Reagan was derided as a “right-wing liberal,” which had special force given that the Gipper came of age as an FDR Democrat, extolling blue-collar economic interests and American strength in the world.)

The anticommunist touchstone was vital because American conservatism wasn’t a monolith then any more than it is today. Continetti drives home this point: “There is not one American Right; there are several.” Conservative politics have long attracted diverse and even contradictory tribes under its banner. But the alien and hostile communist ideology proved a unique asset to American conservatism—the “harnessing bias” of the coalition, in Buckley’s judgment. The predatory forces of Marxist-Leninism and the evil empire they spawned provoked the ire of conservatives for different reasons: free-marketeers because it was anti-capitalist; religious conservatives because it was hostile to faith; and mainstream conservatives because it was anti-American. But it kept the most destructive elements of each faction at bay. The peaceful conclusion of the Cold War owed in large measure to the conservative determination to reassert the originally liberal project of political-ideological warfare against Moscow and to end the era of détente and “coexistence” by rolling back Soviet dominion.

No good deed goes unpunished, and the gash that the fall of the Berlin Wall inflicted on American conservatism was not a shallow one. Continetti notes in passing that the Soviet collapse left the movement “looking for a new purpose,” but he might have made more of the ideological havoc unleashed by this historical development. Deprived of the Red Menace, the Right became openly fratricidal as a growing band of “anti-globalists” and philistines dissented from its internationalist character and belittled its hard-won economic and foreign policy successes.

The paleoconservatives rose to prominence in the decade after the Cold War. Led by former Nixon speechwriter Patrick Buchanan, these forces advocated “a new nationalism” and “a belief again in America First, if not forsaking all others, at least before all others.” This harkened back to conservatism’s impoverished interwar ideology of a crabbed populism joined with disdainful nationalism, but without its allegiance to constitutional principle. Standing squarely in the foreign policy tradition of Charles Lindbergh and Robert Taft, the return of this old Right called for an end to the expenses and exertions needed to sustain Pax Americana. This vision of Fortress America also proposed reviving the nation’s industrial base by pulling up the drawbridge to foreign trade and foreign labor.

Throughout the 1990s, the Republican establishment faced down this populist insurgency, but while it renounced the substance of Buchanan’s pitchfork politics, it co-opted some of his rabble-rousing style. Practically every conservative of significance indulged this sentimental cant to one degree or another, and the editors of National Review even urged a “tactical vote” for Buchanan in Republican primaries. (A few stalwarts tried in vain to point out to their fellow conservatives that Buchanan’s rearguard campaign was left-wing by any description, and quite radically so.) The fissiparous condition of the Right ensured that no one had the credibility, or much inclination, to take up the task Buckley had once performed of making the movement respectable by confronting and suppressing its most cranky individuals and groups.

The Right shows that American conservatism has been an ecumenical place while remaining tethered, sometimes uneasily, to discernible ideas and ideals. Before the recent revolution on the Right, it contained multitudes: Wedded to inherited institutions, the Right defended the practice of “creative destruction” in the marketplace. Committed to limited government, it also exuded what historian Allan Lichtman called an “engaged nationalism” befitting an imperial republic, comfortable with military action and commitments abroad. But the “big tent” of the GOP has now grown too capacious and become unwieldy. It’s uncertain whether the party of Lincoln will ever lay serious claim to those ideals again.

The changing nature of the Right appeared in stages. First, the Iraq war, although waged with broad bipartisan support, eventually fractured the Republican coalition just as the Vietnam war had fractured the Democratic establishment. The popular discontent over the duration of the war ignited the political rise not only of Barack Obama but also of numerous antiwar figures on the Right. Then, the Great Recession triggered a global financial crisis in September 2008 which exacerbated the anti-elitist revolt. But the clearest proof of the populist turn of the Right was the elevation of Alaska governor Sarah Palin, who joined the McCain ticket in 2008.

Continetti, who previously wrote a hagiography of Palin, writes that her Pentecostal religion and folksy manner meant that “she had more in common with many Republican (and some Democratic) voters than with either Democratic or Republican elites.” More unnerving than Palin’s habit of dropping her “g’s” was what Continetti now concedes was her “lack of experience” and “unfamiliarity with the details of domestic and foreign policy.” This is an awfully charitable rendering of an ostensibly conservative figure who, when asked to identify her favorite American founder, replied: “All of them.” Continetti then suggests that such defects “worried both Democratic and Republican elites.” Coming from the author of The Persecution of Sarah Palin, some of those rightward elites were evidently not nearly worried enough.

From provincial nationalists to saccharine Christianists, flamboyant voices on the wilder shores of the conservative movement proliferated. Fox News became infamous for spinning delusional and feverish narratives, but nobody illustrated the Right’s “irritable mental gestures” (in Lionel Trilling’s antique description) better than Rush Limbaugh. Continetti portrays the bombastic talk radio host in a curiously favorable light, offering that Limbaugh “treated politics not only as a competition of ideas but also as a contest between liberal elites and the American public.” But in what respect was the man who generally incited and exploited the worst passions of his tribe—and who claimed that President Obama “hates this country”—interested in the competition of ideas? Limbaugh’s allergy to prudence and moderation, to say nothing of civility and decency, constantly risked justifying John Stuart Mill’s supercilious remark that conservatives form “the stupid party.”

The rise of the Tea Party coincided with Obama’s inauguration. The protest network stood out for its antipathy to both the Democratic and the Republican Parties, backing anti-establishment candidates and causes in service of a “folk libertarianism” hostile to authority of all stripes. It succumbed to conspiracy theories that Obama, the first black US president, was a foreign import without America’s true interests at heart. In foreign policy, the Tea Party was resolutely noninterventionist while harboring lurid fantasies that the Muslim Brotherhood was threatening to foist Islamic law on the United States. And its economic outlook was avaricious, exemplified by the protester who was reported to have told South Carolina Republican Congressman Robert Inglis at a 2009 Town Hall meeting to “keep your government hands off my Medicare.” This last item was incorporated into the Republican agenda by the GOP’s Obama-era spokesman, Paul Ryan. Ryan hyper-ventilated about the need to radically pare back “entitlements,” but only once the comparatively well-off baby boomers had shuffled off this mortal coil.

By 2016, after years of galloping extremism on the Right, the sternest test of conservative principle—or what was left of it—arose with Donald Trump. It was a flop. In spite of an entire issue pronouncing itself “Against Trump,” National Review basically acquiesced after Trump won the party nomination. Limbaugh endorsed Trump without delay. Palin and the populists were not far behind. After a pathetically weak display of hand-wringing, Ryan and most of the establishment also bent the knee in the interests of pursuing a tax-cutting agenda and securing conservative judicial appointments. Ostensibly adherents to the old and the tried, so-called conservatives now opted for the new and untried in the form of the most temperamentally unfit man ever to hold high office in the United States.

With exceedingly rare exceptions, they still do. During the book launch at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC last week, Ryan was given a seat of honor next to the author to raise the alarm about the acute danger posed to America’s constitutional order from … the Left. Nary a word was spoken about the insurrection suborned by Trump that swept a mob of fools and fanatics into the US Capitol on January 6th, 2021, in an abortive effort to overturn a legitimate election. With Trump still the presumptive head of the party, Ryan had nothing to say about the chronic corruption of the republic emanating from the Right. Instead, the former Speaker of the House intoned the stale refrain that proved so useful to Trump in his initial bid for the presidency: that in 2022 we are (as we were in 2012) at an “inflection point” given the gravity of the impending debt crisis. It has been clear for a long time that Trump was and is a symptom, not a cause, of a deep dysfunction on the Right. If he returns to power, he will not be able—as much as he’d like—to cry with Coriolanus, “Alone I did it!”

Trump is the latest manifestation of a populist tradition stretching back to William Jennings Bryan. Having entered the political fray during the Obama years touting the “birther” conspiracy, Trump has been exhibiting a disordered personality ever since. Following the trail Pat Buchanan pioneered two decades earlier, Trump decried America’s foreign trade agreements, immigration system, and stewardship of the liberal international order. But nowhere has Trump redefined the Republican brand more than in its relationship with patriotism and political leadership. His woeful ignorance of the American political system is outpaced only by his contempt for its precepts and principles. These defects did not stop Trump from winning the Republican nomination and, with it, Executive power. In the process, he stripped his party and American politics of its high purpose and nobility.

Continetti has a better than approximate idea of the ghastly consequences of that violation and plunder for the party and the nation. Trump’s refashioning of the Right was as much demographic as it was ideological. As John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge pointed out nearly 20 years ago in Right Nation, in no other country is the Right defined “so much by values rather than class.” When they were writing, the best predictor of whether a white American votes Republican was not his income but how often he goes to church.

This is plainly no longer the case after the rise of Trump, and Continetti has updated this portrait of the average Republican voter: “In 1992, 50 percent of white voters with a high school degree or less identified as a Democrat—nine points higher than the percentage identifying as a Republican. By 2016, the Republicans enjoyed the support of this cohort, and by an incredible number: 59 to 33 percent.” The party of “WASP blue bloods in New England” and “Elks Clubbers in the Midwest” was no more; it had been replaced by a new base of white working-class and rural voters who had traditionally comprised the Democratic base.

This demographic change also reoriented the Republican Party’s policy agenda and political character. Fearful of globalization, suspicious of America’s foreign commitments, and hostile to the cause of limited but energetic government, the New Right has left America without a party dedicated to ordered liberty and national greatness. The GOP is no closer than it has been in decades to forging a consensus that addresses the daunting challenges of our time. And Trump, evicted from office by the voters before being served with his second impeachment, took his leave with “the Republican Party out of power, conservatism in disarray, and the Right in the same hole” dug by its worst tribunes. Continetti’s conclusion is unsparing: “Not only was the right unable to get out of the hole; it did not want to.”

For anyone vaguely acquainted with the story of the Grand Old Party, this latest sordid chapter of Republicanism—the subversion of American democracy and the diminishment of American leadership in the world—can be strange and bewildering. For anyone invested in this uniquely American tradition of political thought, it has been nothing short of devastating. Nevertheless, it’s the natural upshot of the fatigue and exhaustion gripping the Republican Party combined with the noxious prejudices of its new base under the influence of its present standard-bearer. Despite his 2020 defeat, and his brazen anti-democratic acts that followed it, Trump retains a firm hold on that party, and remains its most probable candidate in the next presidential contest. Whatever the electoral prospects of a Republican Party actuated by the needs and urges of one man, the imprint of conservatism properly understood is unlikely to be felt again anytime soon. Until Trump is unhonored and unsung in the Right Nation, conservatism will continue to be sullied by the association, and deservedly so.

The French philosopher Montesquieu wrote that history was governed not by chance, but by underlying causes. If one lost battle could bring a state to ruin, he argued, “some general cause made it necessary for that state to perish from a single battle.” The same is true of the American Right which has scarcely come to ruin in one fell swoop. The hundred-year war for American conservatism has taken a mighty long time to be so lavishly betrayed, and so decisively lost.