Art and Culture

Heading Into the Atom Age—Pat Frank’s Perpetually Relevant Novels

NOTE: The following essay contains spoilers.

British journalist Ed West recently published an excellent essay entitled “Children of Men Is Really Happening,” in which he tied together the shrinking fertility rate wreaking demographic havoc across the globe and the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, which is also wreaking havoc across the globe. The shrinking fertility rate—or “birth dearth” as some have called it—has been receiving attention for at least a decade now. And almost every pundit who has written about it has evoked either P.D. James’s 1992 novel The Children of Men or Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006 film version, titled simply Children of Men. Both of those pop-cultural products are excellent, but were preceded by the work of a lesser-known writer whose own hit novel about a birth dearth appeared nearly a half-century before P.D. James wrote hers.

The author was Pat Frank (birth name: Harry Hart Frank) and the novel was Mr. Adam, published in 1946. In Frank’s novel, radiation released by an accident at a “nuclear fission plant” in Bohrville, Mississippi (a fictional town named after an actual physicist), on September 21st, 1946, seems to have left every male on Earth sterile. This dire predicament isn’t noticed right away. The book is narrated by Stephen Decatur Smith, a New York newspaperman, who receives a curious news tip from his doctor. Apparently, back in the 1940s, as soon as a woman found out she was pregnant, she would contact the maternity ward of some local hospital and schedule an appointment for her approximate due date. The doctor tells Smith:

“There’s never been less hospital space, compared to the population, than in the last few years, and it has actually been getting worse since the war ended. You see, the increase in the birth rate has been fantastic. You’d think everybody in the United States had settled on one occupation and hobby, and that was producing babies. Why, we’ve been getting reservations for our maternity ward as long as eight months in advance.”

But after September 22nd, the reservations came to a halt. It is now early 1947 and the hospital still hasn’t received any maternity reservations beyond June 22nd—exactly nine months after the accident. Intrigued, Smith begins calling hospitals in other major American cities and discovers that the same thing is happening everywhere. Women are no longer getting pregnant. No babies are expected anywhere in the US, or anywhere else in the world for that matter, after June 22nd.

This may sound like a silly set-up. After all, it wouldn’t take New York’s OB-GYNs months and months to realize that nobody was conceiving children. What’s more, the nuclear accident was so horrific that it virtually wiped out the entire population of Mississippi. After a disaster of that magnitude, scientists would immediately have begun worrying about its effects on, among other things, human reproduction. But in Frank’s novel, nobody puts two and two together until Smith and his editor, J.C., finally figure it out:

I recalled a kindred phrase, after Hiroshima was atomized, about civilization now having the power to commit suicide at will. I thought about it, and I thought of the Mississippi disaster, and the thing began to become clear to me, and I yelled: “When was it that Mississippi blew up? Wasn’t it in September?”

J.C. straightened. “That’s it, of course!” he said. The Mississippi explosion was September the twenty-first. Nine months to the day! Nine months to the very day!”

Frank was a career journalist, and so naturally his fictional journalists are smarter than all the world’s doctors and scientists. But this silliness isn’t unintentional. Although Mr. Adam addresses a serious subject, it was written as a comic novel. At one point, Frank points out that the explosion at Bohrville (think about that name for a moment) wasn’t considered particularly awful because “nobody really missed Mississippi. The explosion wiped out Bilbo and Rankin [two prominent real-life white-supremacist Mississippi politicians of the era whom no progressive would have mourned], and anyway Mississippi was the most backward of states. People felt that if any of the forty-eight states had to be sacrificed, it was just as well that it happened to Mississippi.” If this sounds callous to younger readers, well, bear in mind that in the 1960s many of us used to enjoy a TV sitcom set in a Nazi POW camp. Baby Boomers grew up in the shadow of nuclear annihilation and laughing about it was generally more healthy than crying about it.

Fortunately for humankind, a reluctant hero soon arises, a young geologist named Homer Adam. At the time of the Mississippi explosion, Adam was more than a mile below the surface of the Earth, exploring a lead and silver mine near Leadville, Colorado. This protected him from the sterilizing effects of the blast. Now he is the only male on the planet who can impregnate women (a discovery that comes to light when his own wife, Mary Ellen, discovers that she is pregnant). After Smith breaks the story about Mary Ellen’s pregnancy, Adam becomes a much sought-out individual:

The next few days, I would just as soon forget. It was like the Dione quintuplets all over again, except that in this case it was the father, not the mother, in the center ring … I was hounded, harassed, heckled, harried, quizzed, questioned, cross-examined, badgered, and brow-beaten by the ladies and gentlemen of my own profession until I did not know which end was up, or care much.

The novel’s casual misogyny marks it as a product of an earlier era. But what really marks it as an historical relic is Frank’s attitude towards the American military. At one point he writes, “After the press was reasonably satisfied, the Army moved in. The American Army, when it has a war to fight, is an aggressive, eager, brainy, and enormously efficient organization.” Those were the days. And though it takes a lighthearted approach to its subject matter, Frank’s novel is nonetheless a serious meditation on the dawning of the atomic age and all that it might produce. As one character says to another, “If I were God, and I were forced to pick a time to deprive the human race of the magic power of fertility and creation, I think that time would be now.”

Frank is particularly good at dramatizing the way that even well-intentioned governmental efforts to improve national health can quickly turn into kludgy bureaucracies that end up doing the opposite. When Homer Adam’s status as the last fertile male on Earth becomes known to the world, the American government quickly sets up a National Re-fertilization Project. The plan is to impregnate as many American women as possible via artificial insemination using sperm extracted from Adam’s testes. But when Smith goes to report on what is happening, he discovers that the project has been set up with no concern at all for Adam’s own welfare. In fact, Adam seems to be an afterthought to the bean-counters running the bureaucracy. One such bureaucrat tells Smith:

“We’re really beginning to build an organization, now. Everybody thinks the Chief is the coming man in the Administration. Of course, it has been an uphill fight all the way. First the Interior Department tried to take over, and then the Public Health Service claimed it was their baby. Right now we’re operating under the Executive Office of the President, so we don’t have much budget trouble. The real test will come when we go to Congress for regular annual appropriations. I guess our big break was when we got Adam away from the National Research Council.”

“How is Homer Adam?” I inquired. “I’d like to see him as soon as possible.”

He looked at me, curiously, and then took a pencil from an inside pocket and began drawing a chart on the tablecloth. “Now up at the top, of course,” he went on, ignoring my question, “is the President, and right under the President—” his deft pencil drew a little box and began filling it with names—“is the Inter-Departmental Advisory Committee. They decide top policy.”

“On what?” I asked. “I thought the idea was simply to get Adam in shape and then start producing babies.”

“Oh, no!” Klutz said, startled. “The production end is only the smallest part of it! That comes way down here—” he indicated the bottom of the tablecloth—“in Operations.”

On and on goes Percy Klutz, delineating all the levels of bureaucracy that must be set up before anyone can consider the welfare of Homer Adam. In America, every catastrophe provides infinite opportunities for sucking at the public teat.

Mr. Adam was a hugely successful novel. J.B. Lippincott’s hardback version, published in September of 1946, had been through 13 editions by the time September 1947 rolled around. In “My Day,” her syndicated newspaper column, Eleanor Roosevelt noted that Mr. Adam contained “just enough possibility that it might come true to make one read it with interest.” An Armed Services edition was made available to servicemen overseas. A Book Club edition was published, and a condensed version of the novel was published in Liberty magazine. A paperback Pocket Book edition was published in February of 1948. That edition gives us a hint of what might have made the book so popular, especially among male readers. The front cover poses a teaser question to the reader: “Would you like to be the only man in the world who could be a father?” And it is illustrated by a long queue of young women eager to be impregnated.

Alas, the book itself is not nearly as salacious as that cover suggests. From the beginning, it is clear that Homer Adam can successfully repopulate the United States only if his semen is extracted from him and implanted in fertile young women via artificial insemination (the abbreviation AI appears throughout the book. Back then it didn’t stand for artificial intelligence, a scientific discipline that wasn’t founded until 1956). Nonetheless, in its various editions, the book sold roughly two million copies and allowed Frank to put his journalism on the back burner and become a full-time novelist (he also became a speech writer for JFK).

The book remains in print and ought to be popular with fans of Helen Andrews’s Boomers, Jill Filipovic’s OK, Boomer, Bruce Cannon Gibney’s A Generation of Sociopaths, and other recent anti-Boomer screeds since it posits a world in which the Baby Boom never occurred. Eventually, a cure for male infertility is found (in seaweed, of all things) but it arrives too late to save the Baby Boomer generation. By the end of the novel, reproductive capability is slowly returning to human males but it will take a long time to offset the demographic effects of the Mississippi disaster, meaning that there will be no real Baby Boom, which ought to be music to the ears of people like Andrews, Filipovic, and Gibney.

Mr. Adam was not the only Pat Frank novel that managed to be both influential and ahead of its time. His fourth novel, Forbidden Area, published in 1956, remains relevant today as it concerns an unprovoked attack by Russia (well, the USSR) on a sovereign nation (the US) that threatens to lead to nuclear warfare. As the novel opens, two horny teenagers, Henry Hazen and Nina Pope, are making out at midnight on an obscure Florida beach when they notice a Soviet sub surfacing about a mile off the shoreline. Soon a small powerboat departs from the sub and comes to shore, where it deposits four mysterious characters. Henry and Nina don’t know it yet, but these four Soviet agents have been living for years in a secret Soviet training ground jokingly called Little Chicago and “laid out in a section of the Ukraine so thoroughly and often devastated by drought, famine, and war that it was necessary to evacuate only a few kulaks to clear an area of a hundred square miles.”

Little Chicago is set up just like a small American town, with American-style cinemas and soda shoppes and bookstores. The spies who train there spend years “speaking only English, reading only American newspapers, magazines, and books.” They go to American movies three nights a week, watch American television, learn how to play baseball, and listen to the World Series on the radio. And now they have come to America where they plan to integrate themselves into various small towns, enlist in the American military, and do their best to sabotage American defense systems from the inside.

The influence of Frank’s novel can be seen in a variety of subsequent pop-cultural properties, including the 1961 Nathaniel Benchley novel The Off-Islanders (adapted for the screen in 1966 by Norman Jewison as The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming), the 1959 Richard Condon novel (and 1962 John Frankenheimer film) The Manchurian Candidate, and more recent products such as the TV series Homeland and The Americans. In Frank’s novel, a small group of knowledgeable insiders become aware of a Soviet plan to annihilate the US with nuclear weapons but they can’t get anyone in the military or the government to take them seriously. (In this regard, it even seems to have influenced the recent Adam McKay film Don’t Look Up.)

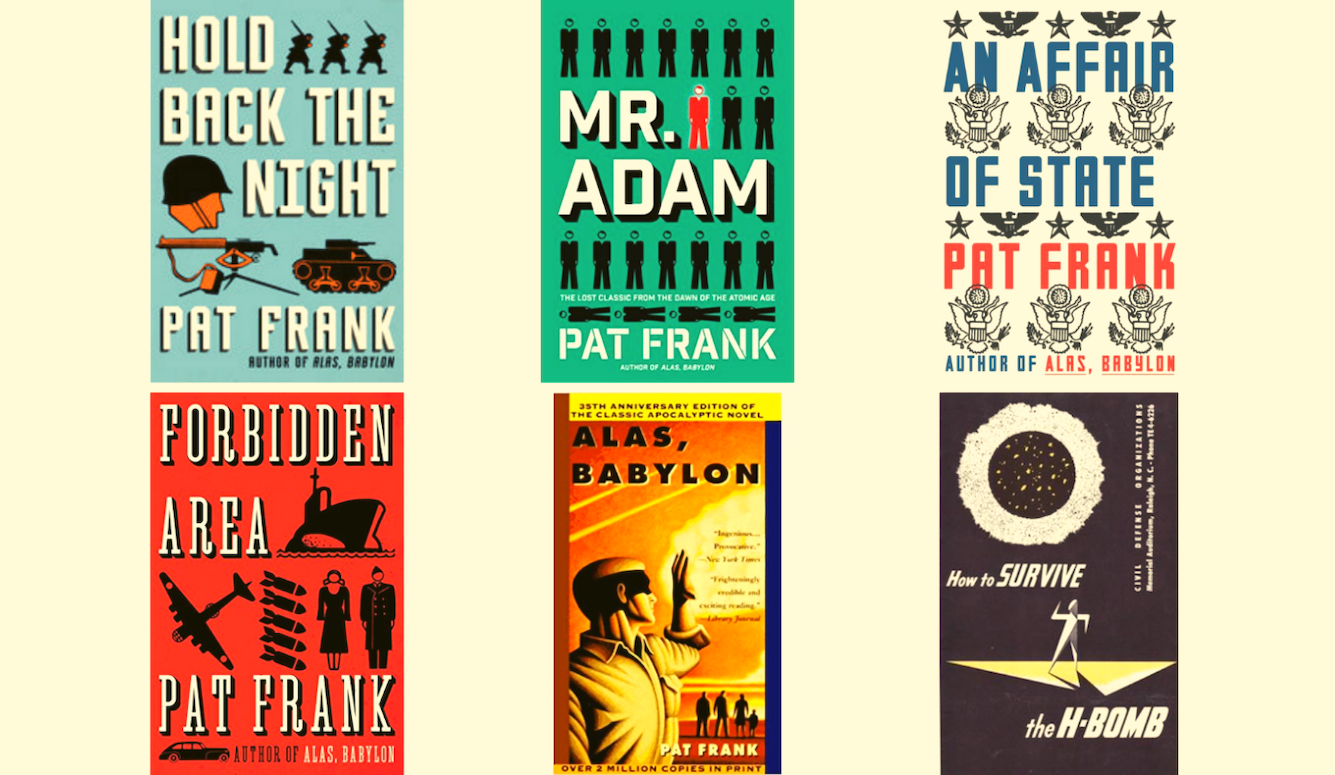

Frank’s 1948 novel, An Affair of State, also seems suddenly relevant, as it deals with the resistance in Hungary to a Soviet takeover. But his biggest selling and most famous novel was his last, 1959’s Alas, Babylon, one of the first great apocalyptic novels of the atomic age. Unlike Nevil Shute’s On The Beach (which preceded it by two years), Peter Bryant’s Red Alert (published in 1958), and Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler’s Fail-Safe (published in 1962), Alas, Babylon was never given the big-screen treatment, and so, though highly influential, probably isn’t as well-known as it should be (Red Alert, by the way, was published first in England as Two Hours to Doom and was the source of Stanley Kubrick’s loose film adaptation, Dr. Strangelove).

Nevertheless, Alas, Babylon has remained steadily in print for more than 60 years. David Pringle included it in his survey of the best science fiction novels published between 1949 and 1984, an honor he denied On The Beach, Red Alert, and Fail-Safe (though not Walter M. Miller Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, a post-apocalyptic masterpiece published the same year as Alas, Babylon). Journalist Harry Kane revealed that John Lennon devoured Frank’s novel in one night, and it had a profound effect on his anti-war stance. The book also appears to have influenced Stephen King’s 1978 epic, The Stand, and David Brin’s 1982 novel The Postman. With Vladimir Putin having recently put Russia’s nuclear-deterrent forces on high alert, Alas, Babylon might suddenly find itself with a whole new generation of frightened readers.

Frank’s last book was a nonfiction work, published in 1962, called How to Survive the H-Bomb, And Why. Like a lot of Americans of his generation (he was born in 1908), he found himself obsessed with nuclear annihilation after World War II. And, like a lot of Americans of my generation (I was born in 1958), I was raised with the anxiety that that obsession created among the young. I was practically weaned on books like Alas, Babylon, Mr. Adam, On The Beach, Fail-Safe, A Canticle For Liebowitz, and the dozens of other nuclear Armageddon books that were published within a few years of my birth.

A lot of people today assume that P.D. James or Alfonso Cuarón invented the tale of how sudden-onset male infertility might someday threaten all human life on Earth. But Pat Frank got there long before they did. He died in 1964 at the age of just 56 (an obituary in Newsweek, published shortly after his death, says that he was born in 1907, not 1908, and that he died at the age of 57). Like everyone else who has fretted about nuclear annihilation since 1946, Frank wasn’t killed by nuclear weapons (he died of acute pancreatitis). Let’s hope that no one ever has to face the fate that Frank wrote so chillingly about and that Boomers like me, who, as schoolchildren, used to practice nuclear attack drills in our classrooms, grew up dreading.