Politics

The Curious Case of Hungary

Hungary rarely commands global attention. This time, however, will be different.

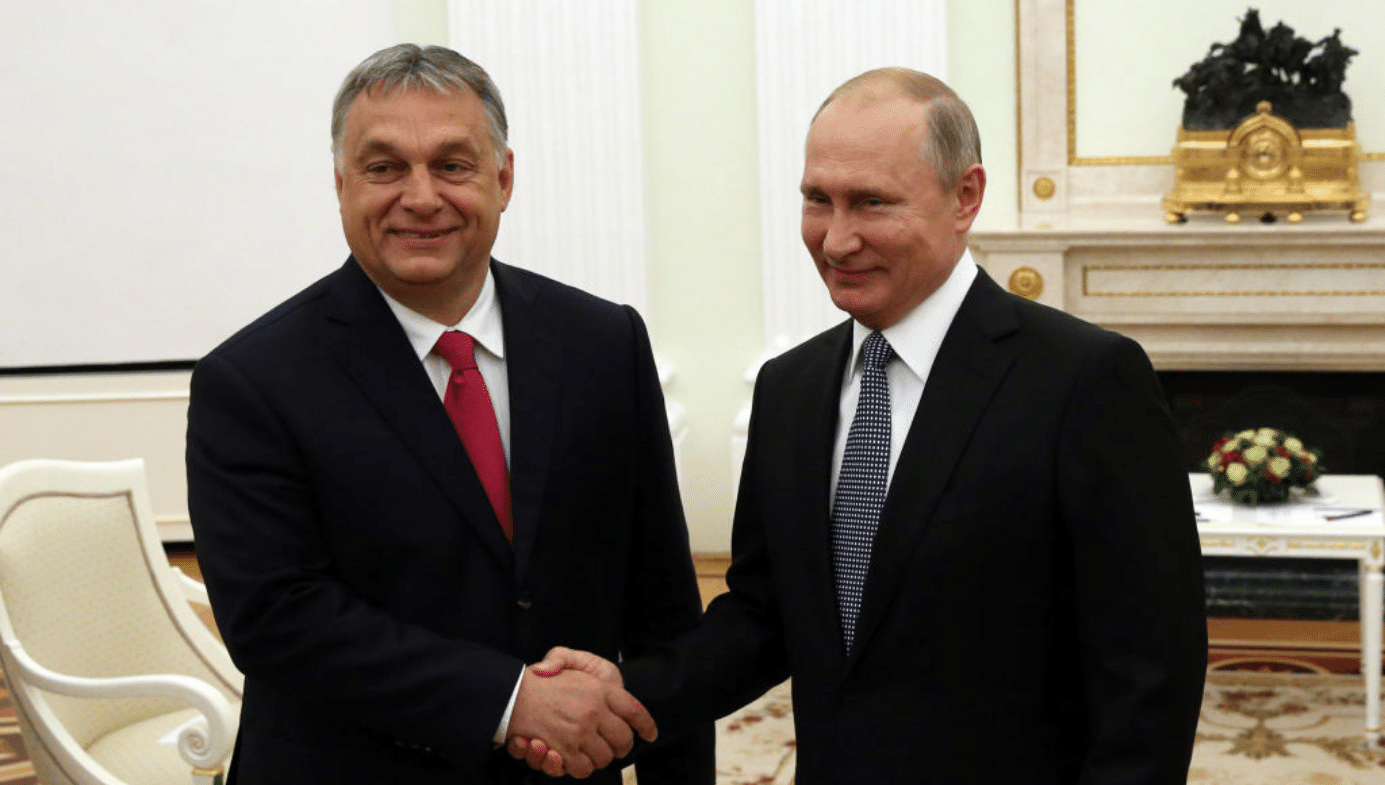

The rapid emergence of anti-liberal political movements in a number of countries over the last few years has taken many political scientists and psychologists by surprise. And the rejection of the liberal democratic model is indeed puzzling, since Western liberal democracies have produced unprecedented levels of freedom, justice, fairness, equality, prosperity, and tolerance. Over the past 12 years, Hungary has become Europe’s self-professed champion of illiberalism, having metamorphosed into a de facto one-party state under the autocratic rule of Putin’s closest European friend and ally, Viktor Orbán. During the unfolding conflict in Ukraine, alone in the EU, all Hungarian state media have faithfully echoed Russian propaganda, blaming NATO and US arrogance for Russia’s horrific crimes.

Why Hungary matters

Normally, Hungary is not an important country—it provides barely 0.8 percent of the EU’s GDP, and rarely commands global attention. This time, however, will be different. Hungary’s slide into a populist autocracy has international ramifications because the pattern is being repeated elsewhere. Orbán’s government has reshaped the country’s political culture and institutions, demonstrating how propaganda, conspiracy theories, and identity politics can be harnessed in the service of ethnonationalism to destroy democratic norms. Orbán already has many followers in Central and Eastern Europe, and has been actively promoting illiberalism in the Balkans.

Unsurprisingly, Orbán managed to make quite an impression on Donald Trump, who showered him with praise for doing such a “tremendous job” during a White House visit in 2019. David Cornstein, meanwhile, an American businessman and close friend of Trump, spent his time as US ambassador in Budapest (2018–2020) undermining efforts to clean up Hungary’s political system. “Cornstein is the worst, most detrimental of diplomats—not just of the United States, but of all the countries,” Transparency International representative and former Hungarian minister Miklos Ligeti told the New York Times in 2019. “He is actively working against the voices of anticorruption.”

Orbán likes to present himself as a champion of conservative values, the family, and Christianity, and as the sworn foe of a destructive neo-Marxist ideology sweeping Western universities and institutions. Some on the Right have eagerly embraced this manipulative narrative, and today Orbán receives a warm welcome at conservative gatherings at which he is invited to thunder against Western godlessness and left-wing tyranny. Paradoxically, then, Hungary’s lurch towards autocracy is drawing a perverse legitimacy from the West’s broader shift toward identity politics.

The growing backlash against political correctness and gender ideology led Orbán to realize that attacking the corrosive influence of radical Western progressivism and its theories generates significant domestic and international support. But, as I have argued elsewhere, the success of the Orbán regime is built on the same populist strategies and ideologies routinely employed by autocracies since the 1930s. As a result, Hungary has become an example to populist political movements and leaders such as the Germany’s AfD, the French National Front, Salvini, Kaczynski, Erdoğan, and Putin, all of whom consult Orbán regularly.

Those of us who value liberty, individualism, and rationality must be careful not to make common cause with right-wing autocrats openly disdainful of Enlightenment values. It is profoundly disappointing to see how some Western conservatives inadvertently legitimize Orbán’s regime. Douglas Murray accepted the hospitality of Orban’s Danube Institute, and Roger Scruton received a medal from Orban. Conservative academics and public intellectuals from the US and Europe have flocked to events organized by Matthias Corvinus College and other Orbánite front organizations. Apparently sanguine about Hungary’s increasingly repressive domestic rule, Fox News’ Tucker Carlson has been happy to embrace Orbán as a defender of conservative values, while ignorant of his systematic destruction of democracy. These endorsements risk inflicting catastrophic damage on the credibility of classical liberalism.

From democracy to autocracy

Following the collapse of the Soviet system, Hungary was widely seen as one of the post-communist countries most likely to make the successful transition from dictatorship to democracy. Unfortunately, this is not how things turned out. Over the past 12 years, Orbán has systematically subjugated democratic institutions and turned the country’s political system into what he euphemistically calls a “System of National Cooperation.”

Orbán was elected in 2010 in a free and fair election to replace the discredited previous centre-Left government, and he immediately set about dismantling the institutions obstructing his pursuit of absolute power. Hungary, he announced, would henceforth be an “illiberal democracy.” He enacted a new constitution supported only by his own party, and changed the electoral law to entrench his control. Although his party failed to win more than 50 percent of all votes cast in either the 2014 or the 2018 elections, on both occasions it nevertheless secured a two-thirds parliamentary majority.

In an extraordinary speech delivered on July 26th, 2014, Orbán declared that Hungary would be turning its back on liberal democracy. Praising autocratic states such as China, Turkey, and Russia, he renounced liberal methods and organizing principles, as well as a liberal way of looking at the world. Contemporary liberal values, he explained, produce corruption, sexual degeneracy, and violence. In illustration of this contention, he is fond of contrasting the vital, work-based economy of healthy Eastern peoples with the tired and immoral Western citizens he says are enslaved by finance capitalism.

Key positions like the public prosecutor’s office, judicial authorities, heads of government agencies, and the tax office were duly staffed with party loyalists appointed for up to nine years. The public broadcaster and 90 percent of the media are now under direct party control, and taxpayer funds are shamelessly used for party propaganda. Corruption has reached unprecedented levels under Orbán’s rule. His childhood friend—a barely literate former gas-fitter—has become the richest man in Hungary in just a few years as the fortunate recipient of countless EU-funded government contracts. Orbán’s son-in-law has been accused of racketeering and criminal conspiracy to defraud the EU by OLAF, the EU’s investigative agency, which has recommended prosecution. But Péter Polt, Orban’s man at the head of the public prosecutor’s office, has done nothing.

Orbán’s strategies to entrench his power are not without historical precedent, but he has been more cunning and successful than many would-be populist autocrats. Political scientists debate how best to characterize Hungary’s autocracy. Some call it a quasi-fascist state, as Orbán’s propaganda fomenting division, hatred, and nationalism employs similar methods to those used by Mussolini, Goebbels, and Hitler. Others, like Bálint Magyar, define it as a post-communist mafia state, on account of the omnipresent corruption and Godfather-like hierarchical power structure documented in Magyar’s carefully researched 800-page book, The Anatomy of Post-Communist Regimes. Transparency International confirms that corruption has become endemic in Hungary since 2010.

In sum, Orbán has used EU taxpayer money to consolidate his illiberal regime, while the EU has been powerless to stop the power-grab and the plunder. The state favours Orbán’s cronies and family members with government contracts, punishes independent media owners, NGOs, and opposition supporters with arbitrary tax investigations, and uses state resources for party propaganda. His party has effectively destroyed the independence of the judiciary, a development documented in Judith Sargentini’s extensive 2018 report for the European Parliament. In many ways, Orbán has excluded himself from the democratic West, and he and his government should be treated accordingly. Criticism from the European Parliament, the Venice Commission, the European Commission, and the Sargentini report have had no discernible effect. Nor has the threat of EU sanctions against Hungary under Article 7 of the EU constitution.

Unrelenting government propaganda has played a crucial role in legitimizing this process, fueling a sense of nationalist self-pity, grievance, and collective narcissism. It instrumentalizes Hungary’s traumatic history to present Orbán as the triumphalist savior of a nation for the benefit of his credulous disciples. The Hungarian electorate is comprised of roughly eight million voters, about a quarter of whom are solid Orbán supporters, and their loyalty has been secured by a combination of ethnonationalist propaganda and targeted favors and benefits.

The coming election

It is against this depressing backdrop that the forthcoming election on April 3rd is being held. But for the first time in 12 years, the opposition has managed to get its act together, and democratic parties from across the political spectrum have formed a common platform to unseat Orbán. In a series of pre-selection votes, a single candidate was chosen for each electoral district to prevent fragmentation of the opposition vote. And in Péter Márki-Zay, a conservative Catholic father of seven, the opposition bloc has found a prime ministerial candidate who actually believes in and lives the conservative Christian values that Orbán only pretends to represent. Márki-Zay is the mayor of a provincial city, lived for many years in North America, has multiple university degrees, and appears to be a decent person and authentic democrat. Needless to say, Orbán’s propaganda machine is now in full swing, attacking him with transparently dishonest accusations.

Leaving nothing to chance, Orbán has done everything in his power to ensure victory. Tens of thousands of loyalist voters from neighbouring countries will be entitled to a postal vote without proper certification, opening numerous avenues for electoral fraud. Meanwhile, more than half-a-million Hungarians who emigrated to Western Europe to escape Orbán’s regime will only be permitted to vote in person at embassies—an unambiguous attempt to reduce their participation. Several fake parties supported by Orbán cronies have also been registered to try and split opposition support. Most state institutions are now run by Orbán loyalists; higher education institutions have been handed over to front foundations run by Orbán appointees for life; the art world, theatres, museums, and granting organisations have all been centralized and are now generally run by party apparatchiks.

Even if the opposition succeeds in winning power, it will be confronted by a phalanx of well-funded and hostile institutions, and barren state coffers emptied by reckless pre-election spending. But this is what makes the coming Hungarian elections so fascinating. We are about to discover whether or not elections alone can provide an autocratic one-party state with a peaceful path back to functioning pluralistic democracy. Many Hungarian commentators are not convinced. Reversals of populist autocracy by democratic means, they point out, are rare in our political history. Some argue that Orbán’s entire 12-year rule was a violation of fundamental constitutional principles, and that a new constitution will be needed to bring those who destroyed our democracy to justice. But this move will no doubt produce new and bitter divisions that make it impracticable.

Those who sincerely oppose the creeping authoritarianism of left-wing revolutionaries, neo-Marxists, critical race theorists, and gender ideologues in our institutions (and I count myself among them) must not allow themselves to be seduced by reactionary authoritarians from the far-Right. We cannot make common cause with genocidal dictators like Putin just because he shares our opposition to political correctness and institutional capture. In the same way, cooperation with an authoritarian like Orbán, whatever its short-term benefits, can only harm the cause of liberty in the long run. Can Orbán still win the election, or can the opposition at last place Hungary back on the road to liberal democracy? We will have to wait to see what happens on April 3rd.