Art and Culture

Fatal Vision: Joel Coen’s ‘Macbeth’

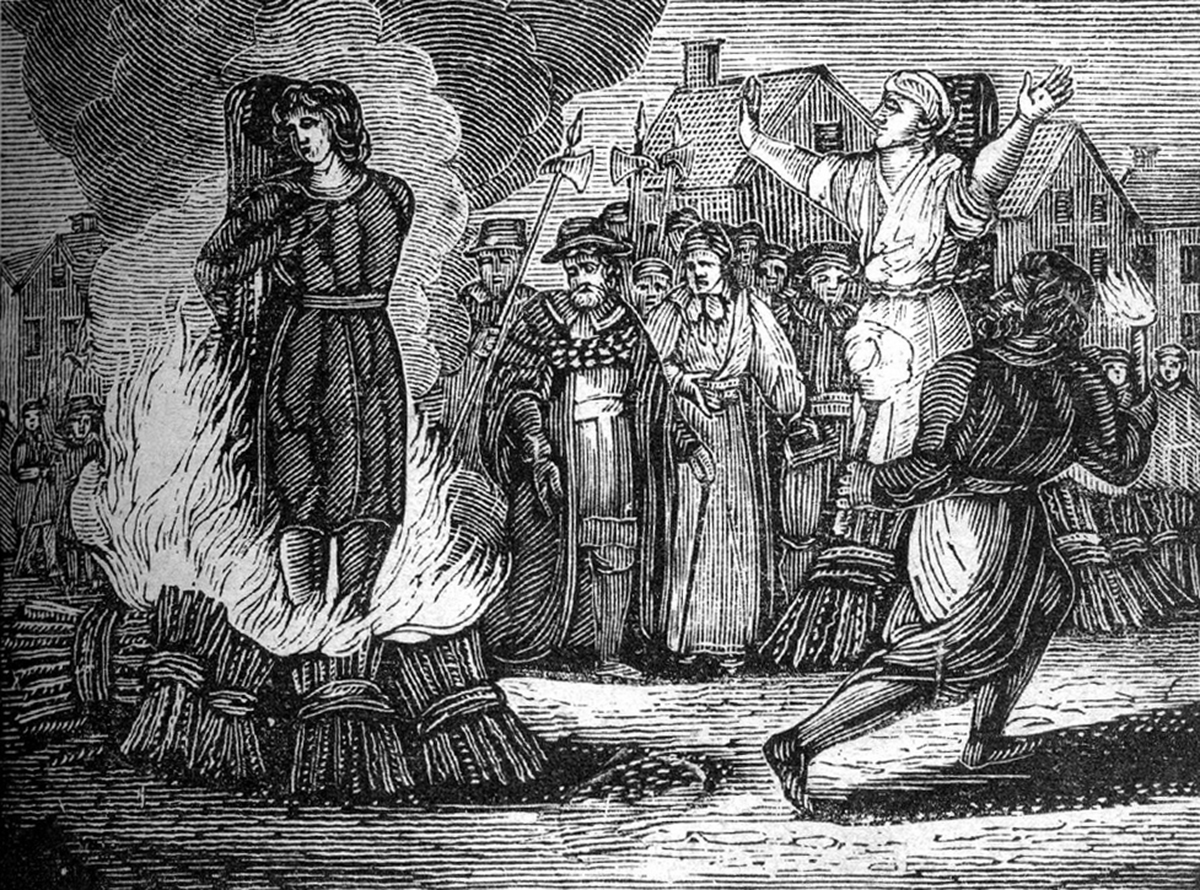

In Shakespeare’s play, the Weïrd Sisters undoubtedly spur Macbeth toward evil by tempting him toward his dark ambition.

“I am in this earthly world, where to do harm / Is often laudable, to do good / Sometime accounted dangerous folly.” So says Lady Macduff in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Moments later, she and her entire family—innocents all—are slaughtered. The triumph of Joel Coen’s film adaptation is that it creates a visual and psychological universe of its own. Watching The Tragedy of Macbeth is like stepping into a surrealist dreamworld. Visually, it is stunning. Yet the otherworldly quality is also its greatest failing. The point of Macbeth is that the horrors of mankind, our darkness and our error, are not a dream, but real. The tragedy of Shakespeare’s play is that good, courageous men and women commit horrors in “this earthly world.” It is not a dream nor a mystery, but the horrifying reality of ordinary evil. The hyper-stylized visuals of Coen’s reimagined Macbeth, through their very elegance, detract from the simply human and everyday moral choices people make in the world as it is.

This isn’t to say that Coen’s film, like the play itself, isn’t steeped in the idea that supernatural forces play a role in our choices. Shakespeare makes it clear that we are constantly engaged in a moral struggle, and that there are real forces of darkness in the world with which we need to contend. Shakespeare shows us that for all the forces that act upon us, good and evil still boil down to human choice. And he shows that our choices are embedded in human relationships and the web of the political order to which we all belong. Bad decisions cut oneself off from community, which is a necessary component of our own humanity. We are, and are not, autonomous. Coen’s film, on the other hand, suggests that our choices are made in a kind of psychological no-man’s land that is largely mysterious to us—hence the need to characterize it as supernatural. It often feels so. Why do we do the things we do? What compulsions or traumas or social forces drive us on?

Coen expresses the felt nature of psychological isolation beautifully. The drama unfolds entirely in either a misty grey landscape or in an austere and angular interior, all of it dreamlike. We don’t just see the setting, we feel it. Missing, however, is the central moral order that Shakespeare’s play dramatizes: the world isn’t an empty, sterile space governed by supernatural forces that spur people of consequence to action. Rather, there is an inherent, coherent, and benevolent order in the world, an order that we often turn away from. An order that links us to each other in bonds of mutual submission, obligation, and care. It is this order that Macbeth violates and that his subsequent torment reveals to be true, for his spiritual anguish is the proof that morality is objective. We live in a thickly moral universe, not in an empty one. This, at least, is what Shakespeare’s play suggests. Coen presents us with a superb visual world, stunning for its emptiness and its absences. Although confronting emptiness is its own form of heroism, the courage of the nihilist shouting into the abyss, the film misses something beautiful within the play itself, making the tragedy less emotionally gripping, and ultimately hardly even tragic.

It must be said that the performances are exceptional. It is especially refreshing to see American actors speaking iambic pentameter in their own accents, and this adds to the emotional honesty each character brings to their role. Denzel Washington has a habit of saying the loud parts quietly, and only rarely gives way to fury. The effect of Washington’s restraint gives his lines an emotional depth that a more volatile, less subtle performance might have lacked. Francis McDormand as Lady Macbeth is likewise restrained and brilliant. Older than many other Lady Macbeths, we are able to see how suffering has hardened her—notably by the loss of a child, or of children—which gives her a kind of stillborn maternal nature. There are moments of tenderness that hint of the marital intimacies to which we are not privy as outsiders to their marriage. And it shows us just what is lost by the Macbeths’ surrender to conspiratorial evil. But it is Kathryn Hunter, who plays all three Weïrd Sisters and the “old man” of Act Two, who is the film’s revelation. The self-assurance with which she plays at being a crow-woman and the vitality she brings to the darkly comic lines of the Sisters, somehow make her performance not at all funny and yet strangely childlike—light, as though she herself is part of the incorporeal air into which she vanishes in the first Act. She is somehow perfectly honest in playing a role imbued with mendacity and malice.

Coen’s expansion of the minor character Ross changes the tone and meaning of this film in an unexpected way. In the play, Ross is simply another nobleman, one who allies himself with the rebels and fights against Macbeth. In the film, however, he is linked to the Weïrd Sisters (he is perhaps a Weïrd Brother), a connection initially suggested by his clothing. While the other men are dressed in leather armour, he is dressed in a long black gown and a kind of angular shawl, made of the same woven fabric as the Sisters’ cloaks. His shawl, both feminine and somehow priestly, hints at crow wings. He is almost unnaturally slender, and seems to glide more than move with footsteps.

Coen inserts Ross most significantly into Banquo’s murder. This scene is a point of mystery and speculation among scholars and directors alike, for Macbeth only commissioned two murderers to kill Banquo, and yet suddenly in this scene there are three. Who is the third murderer? No one can definitively say (he has been variously cast as Macbeth himself, allegorically as Destiny, and most often as simply another desperate cut-throat). By including Ross as the third murderer, Coen places Ross at the centre of the play’s action (and also, not insignificantly, at the death of Lady Macbeth), and thus makes Ross unambiguously the unseen hand that moves Macbeth toward his tragedy. It is Ross who delivers the first part of the Weïrd Sisters’ prophecy to Macbeth, setting the tragedy in motion. Ironically, because Ross is a kind of bridge between the spirit world and the political world, Macbeth’s fall is less a moral mystery than a decided certainty. By placing supernatural forces at the center of Scotland’s political turmoil, Macbeth himself is absolved of much personal responsibility, and the revolutions of kings and noblemen seem less a concern of everyday humans and more the occult movings of a dark world we know little of, a world that works for our ill.

This, then, is a Macbeth for our contemporary moment, where it may indeed feel as though we have little personal autonomy over forces that work both beneath and above us. Entities we can do little to control, or even clearly identify—the bureaucratic rulings of government fiat, the priestly divinations of Silicon Valley’s latest algorithms, the therapeutic and professional experts who direct our social policies—these are the forces that move around us, often in inscrutable ways. Of course, in a liberal society, these forces are intended to work for our good, not, as in Coen’s Macbeth, toward our ill. The liberal belief is that humans are good. It is a flawed society which makes them turn toward evil. Let us fix the society, with our expert wisdom, and we will extinguish human wrongdoing. Conveniently, it isn’t really a moral agent who does good or ill, but the record of malicious social forces that work upon an individual’s unconscious or social standing that is at fault.

In Shakespeare’s play, the Weïrd Sisters undoubtedly spur Macbeth toward evil by tempting him toward his dark ambition. As Banquo says, “oftentimes, to win us to our harm, / The instruments of darkness tell us truths, / Win us with honest trifles, to betray’s / In deepest consequence.” Macbeth cannot pretend he doesn’t know he is in charge of his action. He is told by his trusted friend that his life is not fated and that he is the moral actor not the instruments of darkness. In the play, then, it is decidedly Macbeth’s own ambition that makes him upset the order of the cosmos by murdering king, and guest, and friend. And be in no doubt: Shakespeare’s play, as dark as it is, proclaims that there is an order in the dispensation of the natural and of the political world. Macbeth and Lady Macbeth’s own guilty consciences supply us with the evidence that this is so. Their spiritual and psychological torment are the result of being transgressors in a moral universe. The temptation may have come from outside them in the form of the Sisters, but the guilt is their own.

In Coen’s film, the guilt of Macbeth, and of Lady Macbeth, is much less apparent because they appear to make fewer choices of their own accord. It is Ross who is there, acting behind the scenes, putting pressure on individuals and on events. The result is that the moral core of Shakespeare’s text is strangely absent from the film. In its stead we have a Macbeth who wants the wrong thing because outside forces push him towards it. He is liberal man, corrupted by entities out of his control. He is less of a hero because of it, more passive than the Nietzschean übermensch who simply takes what he wants because he is strong enough to do so. (That said, Macbeth’s murder of King Duncan is bone-chilling. His resolve is expressed extraordinarily by Washington, and the evil of the murder is emphasized by the fear on Duncan’s face. It is an intimate murder, and the more horrible for it. A masterful moment of filmmaking.)

When one reaches the end of Shakespeare’s play, the only redeeming feature Macbeth has left is his courage in the face of damnation. There is something fascinating, even admirable, about such defiance, such rebellion, such loneliness. This is what makes Macbeth a tragedy and not merely a horror story. At the end of the film, however, Macbeth’s character seems diminished, his heroic qualities as a man of will and action shadowed over by the unseen forces that have determined his fate. Coen’s Macbeth is certainly spectacular. But it is just this quality that makes the meaning of Macbeth’s moral struggle likewise seem ethereal and not a real and banal evil of “this earthly world.”