We’re All Going to Get Omicron

My friend Fred (not his real name) is one of the most conscientiously COVID-avoidant people I know. In the pandemic’s early days, he was the guy at my health club who investigated mechanisms we could use to sterilize tennis balls in real time, during play, lest virus particles make their way from one player’s hand to the other, via the pathogenic conduit of yellow nylon fuzz.

So it came as a surprise when, earlier this month, Fred invited a few of us to his apartment for board games. He hadn’t stopped worrying about COVID. But this was a special occasion: A college friend whom we’d both known for more than 30 years was coming to town—call him Craig—and it would be a long time before either of us would get a chance to see him again. So I talked about it with my family, and decided the soiree was worth the risk.

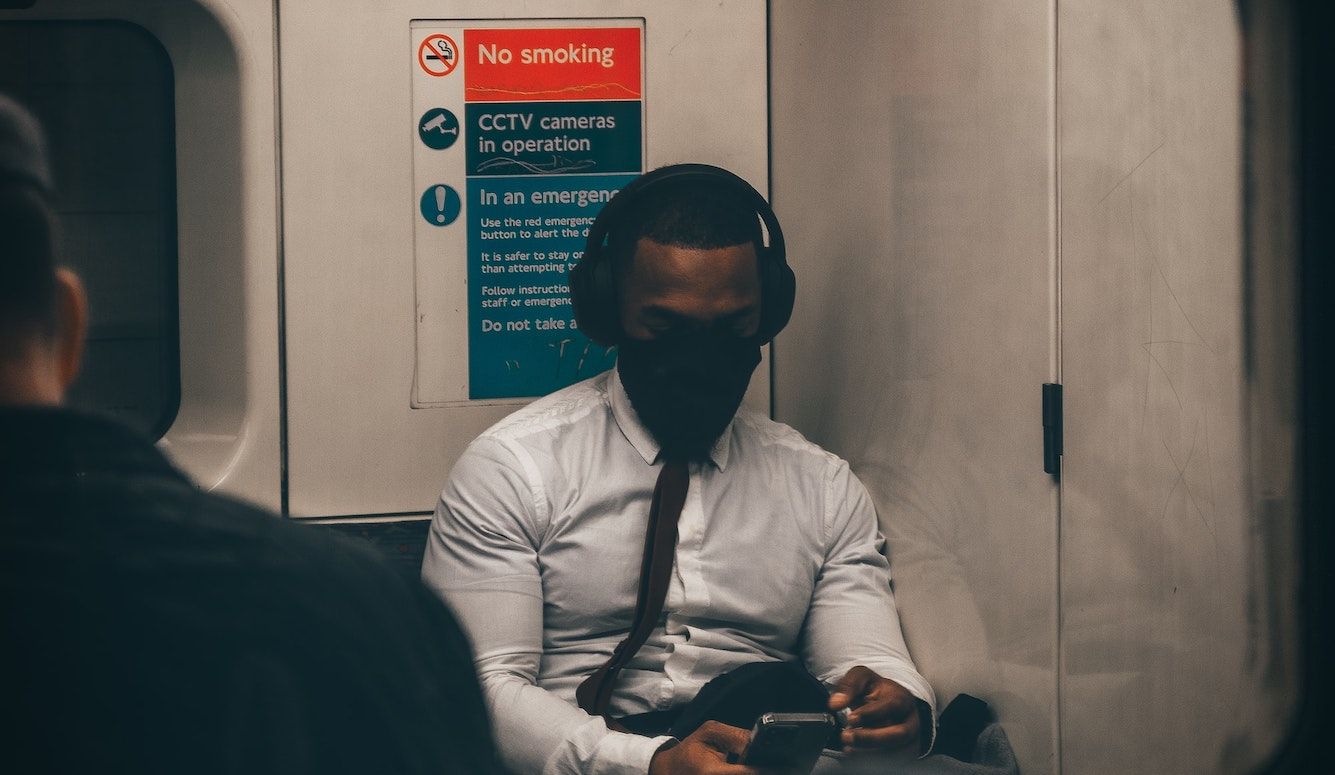

I showed up at Fred’s apartment with a mask on. And, as per our per-arranged plans, I kept it on as I took a rapid COVID test administered by Craig (who’d already passed his own test, as had Fred). We all had a good laugh at the surreal spectacle, which, to pre-2020 eyes, might have looked like some kind of exotic recreational drug regimen.