Work

What is Happening to My Profession?

Some of the people who are refusing the life-saving COVID vaccine are alienated from mainstream institutions, which they view as house organs of the political Left rather than trustworthy arbiters of truth.

Twenty-one years ago, I wrote a book called PC, M.D. How Political Correctness is Corrupting Medicine. One chapter explored “multicultural counseling,” a form of therapy that encouraged white clinicians to ask themselves, “what responsibility do you hold for the racist oppressive and discriminating manner by which you personally and professionally deal with minorities?” Another chapter documented flaws in research studies purportedly showing that physicians, as a matter of routine, were racially biased against their patients. I devoted another chapter to the quest for social justice in the field of public health. In the epilogue, which I called “The Indoctrinologist Isn’t In…Yet,” I cautioned: “those who care about the culture and practice of medicine must be alert to the encroachment of political agendas.”

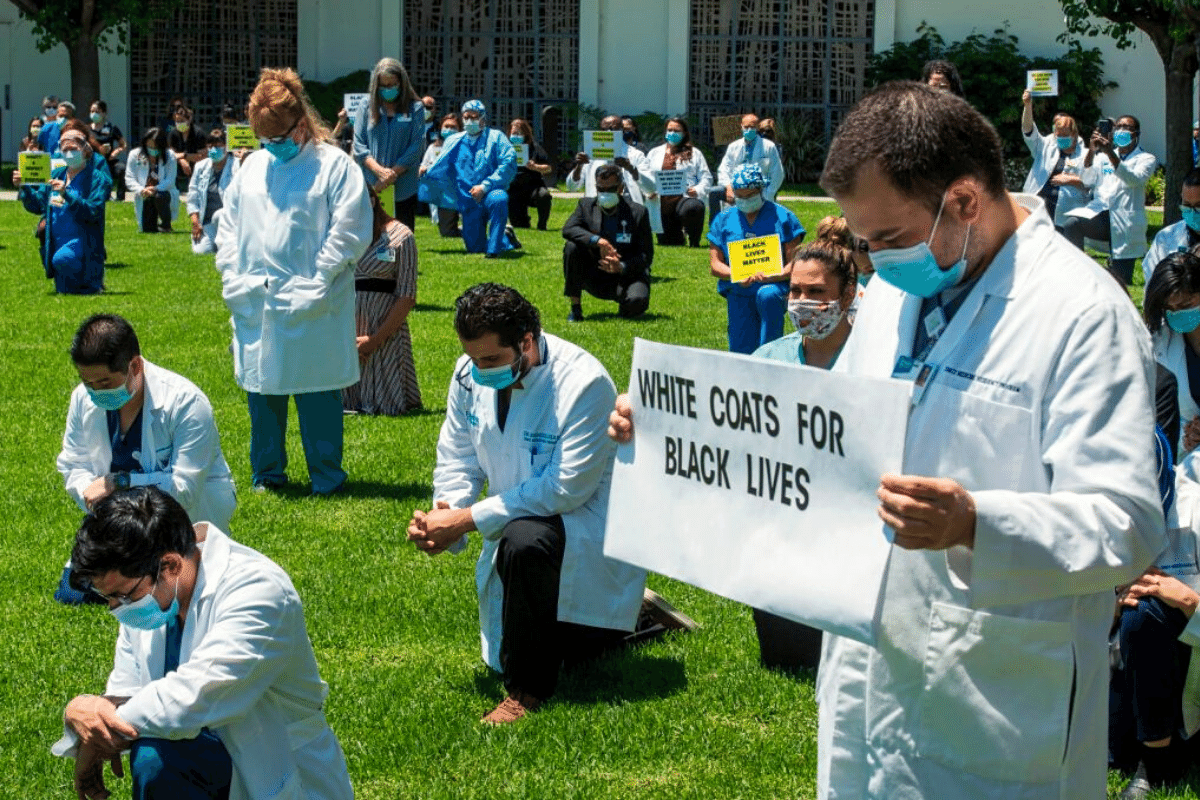

Today, the Indoctrinologists are officially in. These health professionals argued early in the COVID pandemic that, if hospitals were forced to ration ventilators, they should ration based partly on minority status rather than exclusively by standard criteria, such as clinical need or prognosis. They urged vaccine priority for black Americans to compensate for “historical injustice.” And 1,200 of them cheered, via open letter, the message of an epidemiologist from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health who told would-be marchers in the wake of George Floyd’s murder that “the public health risks of not protesting to demand an end to systemic racism greatly exceed the harms of the virus.” In each instance, the experts allowed their own moral commitments, not objective metrics of risk, to shape their advice.

The latest manifestation of Indoctrinology is a 54-page document from the American Medical Association called Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative, and Concepts. The guide condemns several “dominant narratives” in medicine. One is the “narrative of individualism,” and its misbegotten corollary, the notion that health is a personal responsibility. A more “equitable narrative,” the guide instructs, would “expose the political roots underlying apparently ‘natural’ economic arrangements, such as property rights, market conditions, gentrification, oligopolies and low wage rates.” The dominant narratives, says the AMA, “create harm, undermining public health and the advancement of health equity; they must be named, disrupted, and corrected.”

One form of correction that the AMA recommends is “equity explicit” language. Instead of “individuals,” doctors should say “survivors”; instead of “marginalized communities,” they should say, “groups that are struggling against economic marginalization.” We must also be clear that “people are not vulnerable, they are made vulnerable.” Accordingly, we should replace the statement, “Low-income people have the highest level of coronary artery disease,” with “People underpaid and forced into poverty as a result of banking policies, real estate developers gentrifying neighborhoods, and corporations weakening the power of labor movements, among others, have the highest level of coronary artery disease.”

Although the guide contains page after page of “medical newspeak,” as linguist and New York Times commentator John McWhorter called it, a solid kernel of truth lies buried within it. The guide rightly calls attention to the “social determinants of health”—the psychological, social, and cultural contexts that contribute to disease and shape people’s choices regarding their health. The increased awareness of these contexts over the last 20 or so years has been a major advance in medical training. It is indeed important for doctors to realize that even their most motivated patients may not be able to afford a medication, take time from work to keep an appointment, or understand a complex medical regimen. We must be prepared to enlist social workers and case managers to help.

However, the guide recklessly stretches context beyond the realm of clinical outreach. It rebuffs “programmatic fixes,” such as the case manager who arranges for a patient’s transportation, because such fixes “ignore the social responsibility of corporations and government agencies.” With its emphasis on “power relations” and its push to “redistribute power and resources,” the guide reads more like a postmodern manifesto than an actionable blueprint for physicians.

In important ways, I hardly recognize my profession. Last year, the Association of American Medical Colleges, a major accrediting body, informed medical schools that they “must employ anti-racist and unconscious bias training and engage in interracial dialogues.” One of my colleagues told me that her school jettisoned lectures in bioethics to make room for the anti-racist curriculum. “Which is ironic,” she said, “because that was where students were taught about subjects like the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.” What other essential subjects will anti-racism training displace?

The implementation of the social justice agenda has constrained collegial discourse, challenged the maintenance of standards, and suppressed honest analysis of certain problems. In her article called “What Happens When Doctors Can’t Tell the Truth?,” Katie Herzog wrote of “doctors who’ve been reported to their departments for criticizing residents for being late. (It was seen by their trainees as an act of racism) … I’ve heard from doctors who’ve stopped giving trainees honest feedback for fear of retaliation. I’ve spoken to those who have seen clinicians and residents refuse to treat patients based on their race or their perceived conservative politics.”

Two cancellations have attracted notice. Last year, Norman Wang, a cardiologist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine who expressed skepticism about mandatory affirmative action after conducting a careful review of the data was stripped by his department of his directorship of the electrophysiology fellowship and barred from having contact with medical students, residents, or fellows because his views were “inherently unsafe.” His peer-reviewed paper, ‘Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity: Evolution of Race and Ethnicity Considerations for the Cardiology Workforce in the United States of America from 1969 to 2019,’ which appeared in March 2020 in the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA) was retracted by the journal without Wang’s consent. The American Heart Association, which publishes JAHA, tweeted that his article “does NOT represent AHA values.” The cardiologist has sued both the university and the American Health Association.

In another case, the editor-in-chief of the Journal of the American Medical Association was effectively forced to resign last June for a somewhat tone deaf, but otherwise unremarkable, 15-minute podcast on racism in medicine and because of a tweet advertising it. “Although I did not write or even see the tweet, or create the podcast, as editor-in-chief, I am ultimately responsible for them,” he said in a statement. What other examples have escaped attention? “Most who are troubled by this are keeping their heads down and keeping their mouths shut,” said my colleague Thomas Huddle, an internist and professor who retired this year from the medical school at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, one of the few physicians willing to go on the record. “They’re deeply afraid of social media mobs and of academic administrative superiors who’ve taken this stuff on,” he said of his colleagues to Real Clear Investigations.

Especially vexing, as Huddle and I have commiserated, is the reflexive attribution of group differences to systemic racism. “It’s axiomatic at this point,” said a colleague who had participated in a group discussion of stress and rising suicide in black youth. The tacit rule was that only fear of police aggression and subjection to racial discrimination were allowable explanations, not the psychological torture of bullying by classmates or the quotidian terror of neighborhood gun violence.

I strongly agree that much of black Americans’ disadvantage in health and access to care is the cumulative product of legal, political, and social institutions that have historically discriminated, and sometimes continue to discriminate, against them. Systemic racism may indeed have broad explanatory value regarding health disparities, but, as an analytic framework, it doesn’t yield realistic prescriptions. Just what are physicians supposed to do? Become activists? The AMA’s answer is yes. In a strategic plan it released last spring, the organization urged doctors to “push upstream to address all determinants of health and the root causes of inequities, dismantle structural racism and intersecting systems of oppression.”

This is no solution. Physicians cannot—and should not—“dismantle racism and intersecting systems of oppression” as part of their clinical mission. To imply that such activity falls within our scope of expertise is to abuse our authority. Doctors can reasonably lobby for policies directly promoting health, such as better coverage for patient care or more services, but we will lose our focus and dilute our efforts to care for patients if we seek to address the perceived root causes of health disparities.

After all, even seasoned policy analysts can’t readily tease out strong causal links between health and sprawling upstream economic and social factors. With so many intervening variables at play, reforms in the service of health may well create unwanted repercussions elsewhere in the system. Any physician is free, of course, to pursue progressive reform as a private citizen but, as doctors, we already have a job: to diagnose and treat.

Still, much can be done to expand immediate access to treatment for underserved minority populations. In California, for example, when patients with colon cancer were treated at an integrated health care system—a point of entry where all aspects of care were delivered under one roof—black patients fared much better than black patients treated in usual settings. As a result, survival rates were the same for blacks and whites. The Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force reduced mortality by helping women, mainly black women, navigate the health care system. The Comer Children's Pediatric Mobile Medical Unit brings service to Chicago's South Side, including immunizations, physicals for school, and screenings for vision, hearing, lead poisoning, and anemia. Medical centers partner with inner-city barbershops to help black patrons control diabetes and high blood pressure and to prevent heart attack and stroke. These community-based projects may not be the seeds of revolution, but they can improve and save lives.

On January 8th, 2021, I had my own encounter with intolerance in academic medicine. Via Zoom, I gave a Grand Rounds lecture to the Yale Department of Psychiatry, where I had been a resident for four years and an assistant professor for five. I left New Haven in 1993 to pursue a health policy fellowship in Washington, DC and eventually joined a think tank there, but remained a lecturer in the department. My talk was about the year I spent assisting with treatment efforts in Ironton, a small, embattled town in south-eastern Ohio that was reeling from the opioid crisis.

I discussed the “deaths of despair” phenomenon and showed photos of haunted industrial landscapes and the lonely downtown area. I presented national data on the characteristics of individuals who abused prescription pills and on the frequency with which addiction develops. I talked about the culture of prescribing in rural mining towns and the myriad factors that caused the crisis. I closed by highlighting the heroic efforts of Irontonians to boost the economy and the morale of their beloved town.

One month later, I received an e-mail from the chairman of the department, a fine man and brilliant researcher whom I have known since we were interns together in the 1980s. He admitted that he had not anticipated “the extent of the hurt and offense that folks would take” to my presence. He appended an anonymous complaint that he had received from an unspecified number of “Concerned Yale Psychiatry Residents.”

The residents told the chairman that my talk, coming only two days after the January 6th attack on the Capitol, “was further traumatizing to us.” They wrote that, “the language Dr. Satel used in her presentation was dehumanizing, demeaning, and classist toward individuals living in rural Ohio and for rural populations in general … We find her canon to be beyond a ‘difference of opinion’ worth debate.” My earlier writing on health disparities was deemed a “racist canon.” They expressed “shock and disappointment” at the chairman’s failure to “take a public stand against” me and questioned his commitment to the department’s anti-racist agenda. “Will you continue to invite Grand Rounds Speakers with racist and classist mindsets, like Dr. Satel?” the residents asked. Although they requested that the chairman “revoke” my lectureship at Yale, he did not do so.

Academic medicine is in the midst of a risky institutional experiment. How will the AMA’s new call to “focus attention on inequitable systems, hierarchies, social structure, power relations, and institutional practices” affect the formation of trainees’ professional identities? Are we truly to believe that health is so thoroughly contingent on malign forces that doctors shouldn’t bother educating patients about how they can take responsibility for their wellbeing? And how will the adoption of a zealous social justice agenda affect public trust?

Some of the people who are refusing the life-saving COVID vaccine are alienated from mainstream institutions, which they view as house organs of the political Left rather than trustworthy arbiters of truth. They may see the AMA’s prescription as further confirmation of their suspicions.

Most important, will patients benefit when the AMA and other leaders position medicine as a vehicle for activism? We must remember that “Do no harm” is a covenant that doctors make with their patients, not with political systems and hierarchies.